I must admit, I loved the Bob Dylan bio pic, A Complete Unknown. The songs of Dylan play a key role in the film and their power is what makes the movie worthwhile. I was also impressed by the evocation of the Greenwich Village folk scene during the early 1960s.

However, James Mangold (the director of such recent films as an Indiana Jones and the Dial of Death, Ford vs Ferrari, and two Marvel super hero flicks, Logan and Wolverine) has produced a predictable bio-pic about Dylan’s arrival in New York in 1961 and his rupture with folk music four years later. Most disappointing was the treatment of Pete Seeger as a saintly but ultimately artistically limited Dylan supporter.

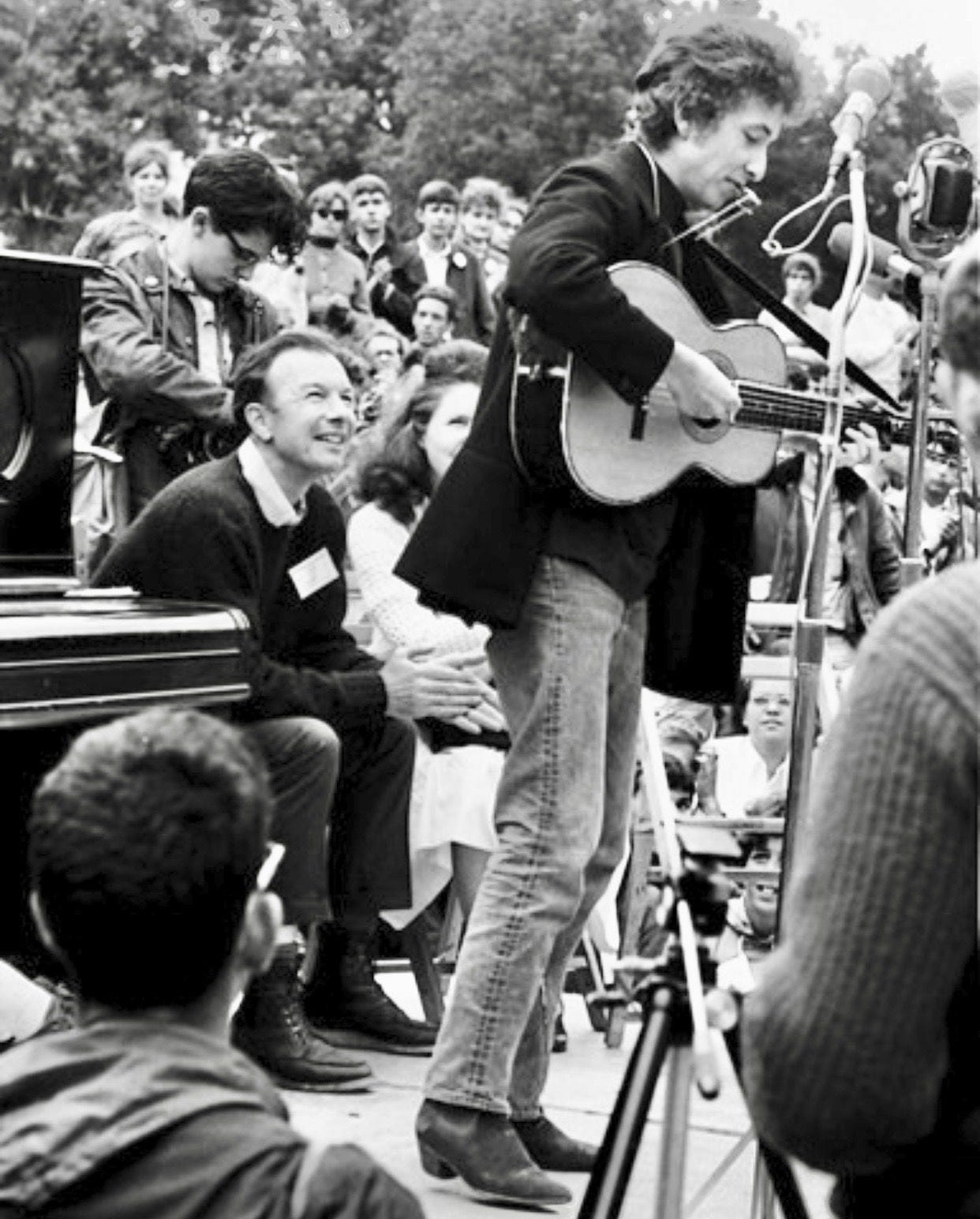

The film opens with Dylan arriving in New York after hitch-hiking from Minnesota. We see him jump into the Greenwich Village folk scene, meet Dave Von Ronk (a major figure in that scene, and the basis for the much better film by the Cohen brothers: Inside Llewyn Davis) who tells him which hospital the dying Woody Guthrie is located. Dylan goes to visit his hero and meets Pete Seeger who immediately recognizes his talent and becomes his sponsor. From then on it is the usual bio-pic depiction of a musical genius’s rise to fame and adulation.

Our hero ultimately grates under the confines of the tradition-bound folk/protest movement and pushes for greater artistic freedom. This culminates in the 1965 Newport Folk festival where Dylan goes electric and an outraged Seeger tries to cut off the performance apocryphally with an axe. The short-sightedness of Seeger’s action is reinforced in the final scene in which Dylan revisits Woody Guthrie one last time and Mangold has the semi-comatose folk hero apparently bless Dylan as the inheritor of his legacy of artistic individualism. What horseshit!

There is no denying Dylan’s musical genius, how he redefined not just folk but popular music more generally, created the folk-rock synthesis, and introduced poetry to the lyrics of popular music. Dylan was a modern Mozart. But how ever big Dylan may have been as a musician, he was a political midget in comparison to his mentor Pete Seeger.

Mangold, views Pete as a saint, but one whose political moralism blinds him to what Dylan was doing for the stagnant blind alley that folk music had become. His attempt to “use the axe” to cut Dylan’s performance was the ultimate expression of Seeger’s limitations. Even Pete himself seems to have later come around to this view, admitting that he had been wrong, but claiming he supposedly only wanted to turn the electric guitars down so Dylan’s lyrics could be heard.

But I believe that Seeger’s actions in 1965 were more complicated than Mangold’s simplistic portrayal would have us believe . More importantly, Seeger’s actions speak to us today in a way that is a model for those of us who must stand up for our values during difficult political times. The form of music that Seeger was defending at Newport was more than an expression of art, but of a political movement as well. This was a movement that Dylan had posed as a supporter of for a few years, but never really understood. Seeger, on the other hand, had spent his life supporting that movement, even when it was not popular.

In the late 1930s with Guthrie, Seeger had supported the union movement with songs and benefits; in the mid-1940s he had opposed the internment of Japanese Americans, which got him placed on the FBI’s subversive list; during the 1950s he had been an early supporter of the Civil rights movement. Let’s remember that the 1950s and early 1960s was a time of political capitulation (not unlike our own) in which many on the left had been intimidated into staying silent against McCarthyism. Purges led by right-wing extremists had removed left of center supporters from the union movement, academia, and government. Seeger’s refusal to capitulate to McCarthyism meant he had been blacklisted, lost gig after gig, and was banned from appearing on national television.

In 1965 alone, the year of the “axe incident” at Newport, Seeger had been in Selma to support the marchers after “Bloody Sunday” (when John Lewis was beaten). That summer, the number of US troops sent to Viet Nam had exploded and opposition to the war had grown along with it. A number of young Americans had begun burning their draft cards as protest, and in response, President Johnson had made draft card burning a felony. Seeger had spoken out in defense of these protesters and the larger anti-war movement, which had gotten him wired tapped by J. Edgar Hoover’s FBI.

What had Dylan been doing in1965? This was the year in which he had gotten sucked into heroin addiction and introduced the Beetles to drugs. This was also the year when he made his tour of England—the basis of the film Don’t Look Back –which had made him an avant-garde icon. It was on this tour that he famously degraded Joan Baez and her politics. This was not the only sign that Dylan had begun to thumb his nose at his previous political involvements. In his song “My Back Pages’ (on the album The Other Side of Bob Dylan), which had come out a few months before Newport, he sang that causes and people like Pete Seeger were “…ancient history flung down by corpse evangelists unthought of, though, somehow.”

All of this was the backdrop for Seeger’s anger at Newport. While Seeger may have been unable to understand Dylan’s artistic transition, Dylan was unable to understand Seeger’s political fortitude. For Dylan these movements and struggles were a suit of clothes to be abandoned when they no longer fit current fashion. For Seeger, they were his life’s work for which he had faced jail, blacklisting, and the accusation of treason. It wasn’t just the sound of the electric guitars that Seeger was trying to stop, but the lyrics that betrayed movements he had spent his life supporting.

So Seeger had a right to look for that axe. Political principles are not identical to artistic ones. When someone uses a political movement like Civil Rights as a steppingstone and then derides that movement, anger is not only understandable but necessary. Seeger was looking for an axe to defend movements like Civil Rights as much as his version of folk music. Political authenticity is complicated: its weaknesses can also be its strengths. It can be blind to artistic creativity, but it can also produce the courage to stand up for principles against the threat of repression. Hopefully, there are still people in our movements today with Pete Seeger’s form of political fortitude. I am afraid we are going to need it.

Gregg Robinson is a long-time activist, retired Grossmont College Sociology professor, San Diego County Board of Education member, and a member of the AFT Guild, Local 1931 Retiree Chapter.