By Larissa Dorman-Cobb

“The years rolled slowly past

And I found myself alone

Surrounded by strangers I thought were my friends

I found myself further and further from my home, and I

Guess I lost my way

There were oh-so-many roads

I was living to run and running to live

Never worried about paying or even how much I owed

Moving eight miles a minute for months at a time

Breaking all of the rules that would bend

I began to find myself searching

Searching for shelter again and again” -Bob Seger

April 27th, 2019

I had heard talk of the connection a parent has with their child–the capacity to feel their pain, to experience their joy, to know if there’s something wrong. This connection spans space and time and bridges generations. I had heard less about our ability as children to feel those same things for our parents.

On a beautiful spring day, I felt the last day of my father’s life from over 1,000 miles away, without a way to connect to him, without a way to share those last moments, knowing that our time together here was coming to an end. I shared with my partner that I was feeling my father pass over, though this would not be confirmed until a few days later with a call from the Washington State Coroner’s Office that my father died from severe tuberculosis. This was a call that would both change my life and fill me with immense gratitude for the power of our love for each other.

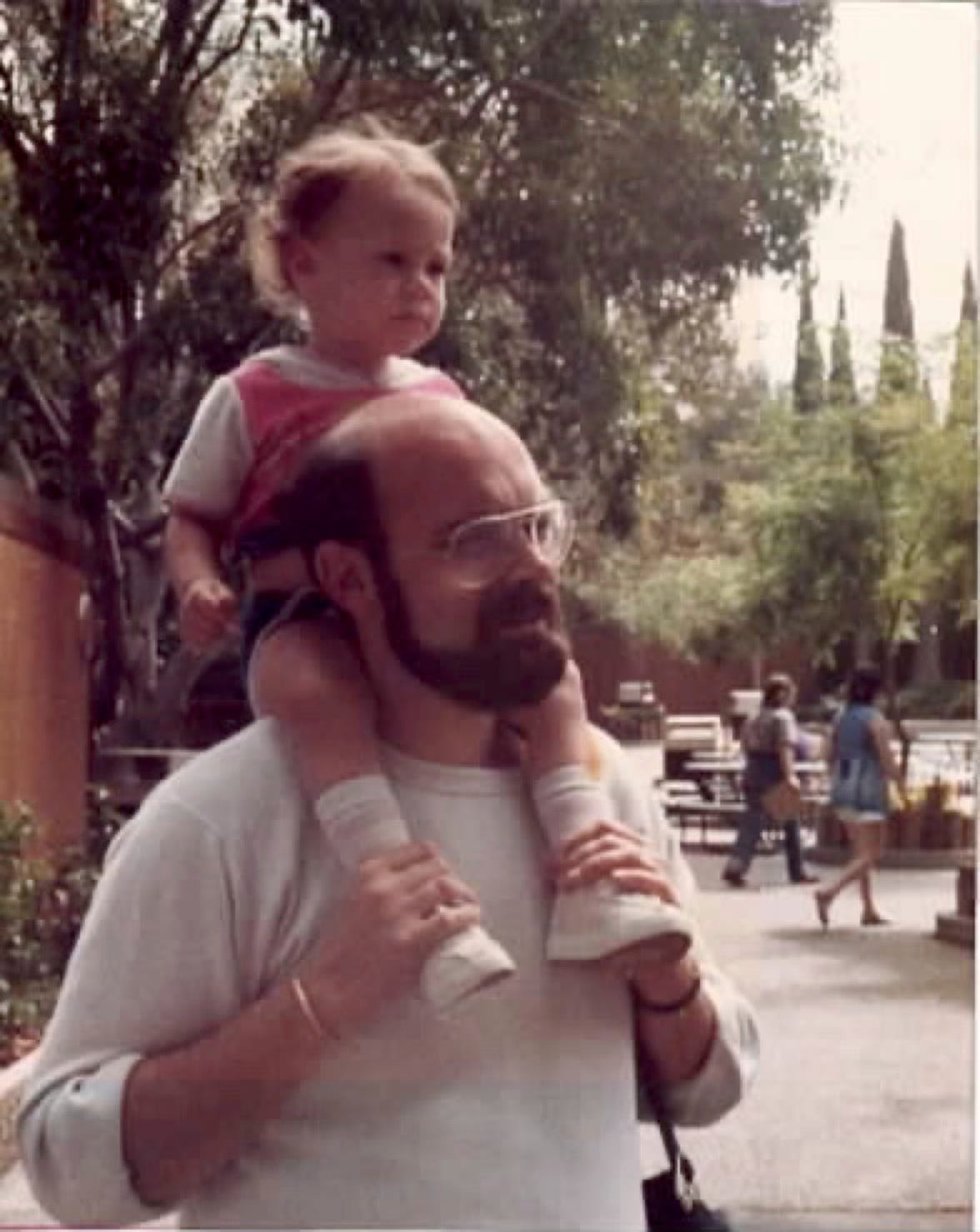

To be clear, my dad was an asshole, an imperfect human who was addicted to scotch, coffee, and cigarettes. He had a difficult time managing his anger and made the lives of his wife and four children hell most evenings. It wasn’t always this way: my young childhood was filled with camping, fishing, hiking, walking the beach, throwing a football, belly laughing and wrestling tickle fights. He played the albums of Zeppelin, Seger, Croce and Cream on repeat in our home.

Dad worked hard, lived hard, played hard–but his humor and brilliance could never overcome his deep trauma. When drinking, he took on other personalities and believed he was a sniper in the midst of a war or a CIA spy. He claimed he had people following me to keep me safe. His break with the world was deep and terrifying.

January 1st, 1994

Every part of my life has been impacted by a single policy, NAFTA. My father was a craftsman, an artist, an outdoorsman, a voracious reader, a mathematician, a creator, a tradesman, a draftsman and a proud skilled worker. He apprenticed under his Romanian grandfather to become a machinist, tool and dye, welder and mold designer. Although my dad could have easily become an academic like his physician father and scientist mother (family lore claims that he had a Mensa level IQ that they expected to be used in the “professional class”), he was drawn to making things with his hands, solving puzzles, and doing it better than everyone else.

He took great pride in the fact that the molds he designed were more accurate than anything a computer could generate. I remember a day when he took me to his machine shop in Alpine to show me his latest creation–a mold design that would create plastic devices that would eventually be used to save lives. To create the perfect mold, you had to mathematically determine its opposite, each curve, each angle had to be in alignment. In the 1980’s and early 1990’s, there was a belief that his work would always be needed in America, that there were only a handful of people skilled enough to do it well and as such there was no need for a union.

And then NAFTA happened.

Overnight entire industries were packed up and moved across the border. The machines, the jobs and the futures of almost 700,000 workers were gone. NAFTA led to rising inequality, suppressed wages for American workers and the weakening of unions. It made working people in this country feel disrespected, disposable and isolated-the antithesis of the aims of the labor movement. It allowed capital to travel across borders and billionaires to be made.

Some people might have decided at 41 that they could start over…not my dad. His work was his identity and his connection to his grandfather. He was broken and his already traumatized constitution could not suffer another blow. He tried to piece together work where he could for another year but finally recognized that the future he had planned on was over and he would rather not participate in this society, at all.

By 1995, my parents had divorced, my mother was forced to contend with a future without her partner, without child support and with the echoes of trauma impacting her children daily. She struggled to find rental housing that she could qualify for and afford with 4 kids, a dog and two cats. She went back to school to finish her degree and become a teacher while fighting off creditors and barely making ends meet.

She worried constantly that we could lose our home and her worry was very real: my father had become unhoused. He lived on the streets of San Diego and read books at the public library or neighborhood parks all day. He found enough money from friends and family to keep drinking and, 21 years later, his life looked much the same. By then he had relocated to Seattle hoping to find work, trying to battle the dragon of his addiction, picking up odd jobs where he could and for fun, learning how to code on a laptop he kept in a train terminal locker.

I had no way of reaching my father, he had no cell phone or landline so he would borrow a friend's phone from time to time, and I would answer any 206 area code whenever I could. We talked politics, books, music, and he was immensely proud that I had become a political science teacher and union activist. He apologized for the impact of his behavior and at times showed another personality, that of a Buddhist monk sharing incredible insight.

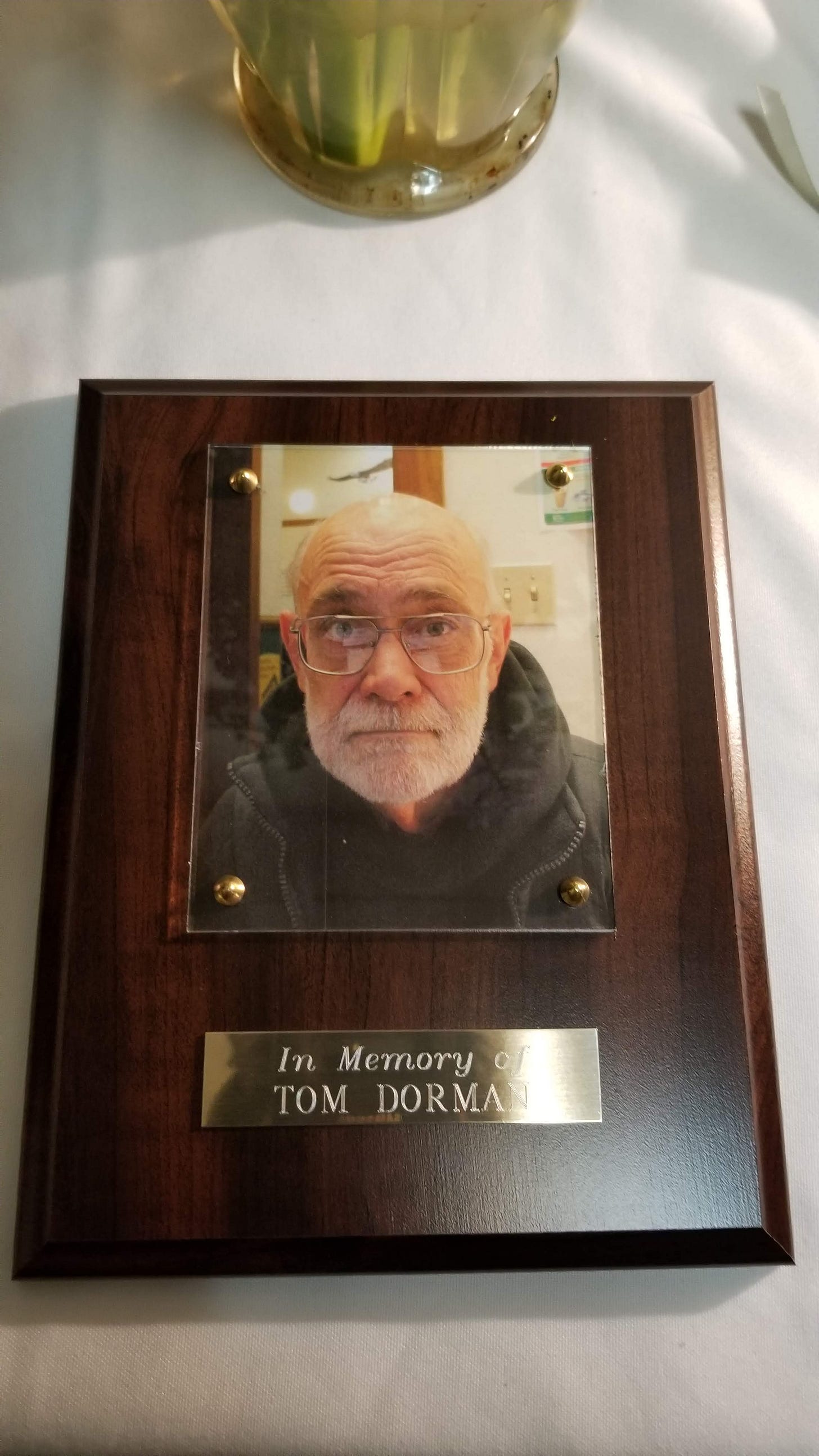

My father died alone in a single occupancy style room run by Catholic Charities for unhoused men over 60. It was his place of refuge for 3 years before his death after over 20 years on the streets—a place where he began making amends but also where he contracted the disease that would kill him.

Most people would tell you that my dad was antisocial, anti-authoritarian, anti-everything. Only a few were lucky enough to know he was also deeply sentimental and thoughtful. When he passed, one of the young social worker interns at the organization shared a few stories about him.

In one, she told how she’d shared with him her plans to hike the Pacific Crest Trail to celebrate her graduation as a social worker–little did she know my father dreamed of hiking the same trail for decades. A few days later, he had dropped off a book and map with all the stops outlined and places to rest marked for her journey. He had spent countless hours researching and planning a trip he would never get to take himself.

As we were negotiating his few belongings that remained, items that included photos of his children and books on coding, she asked if she could keep the map and directions for her journey to honor him on this passage. I like to think he was there with her along the way.

Larissa Dorman-Cobb is the Organizing Coordinator for the AFT Guild, Local 1931 in San Diego.