Animated Cartoon Sponsored by Union Played Role in Reelecting Roosevelt

The Labor History Corner--an excerpt from "From Mission to Microchip: A History of the California Labor Movement" By Fred Glass

A version of this article appeared on the California Labor Federation California Labor History website. You can buy From Mission to Microchip: A History of the California Labor Movement from the University of California Press.

Approaching the 1944 presidential election at the height of World War II, it was unclear whether Franklin Delano Roosevelt, already elected to an unprecedented three terms, would make it to the finish line again. The Democratic Party had taken a battering in the 1942 congressional elections, with their Republican opponents picking up nearly fifty seats. The Democrats retained a slim majority, but momentum seemed to be going in the wrong direction. Creative action to win the election was called for.

In early 1944, United Automobile Workers-CIO leaders commissioned a group of Hollywood animators to produce a short film for the Roosevelt reelection effort. The Republican gains in the 1942 election had resulted in passage of the Smith-Connally Act, which among other anti-labor measures forbade direct union political contributions. In response the CIO formed the first political action committee, or PAC, which channeled worker political contributions into a fund one legal arm’s length from the methods prohibited by the Act.

With this CIO-PAC money the recently formed Industrial Films and Poster Service (later UPA) gathered a talented crew headed by Warner Brothers animation director Chuck Jones (best-known for his Bugs Bunny cartoons). It included famed progressive songwriter Earl Robinson (“I Dreamed I Saw Joe Hill Last Night”), Academy Award-winning Wizard of Oz lyricist Yip Harburg, movie star and Screen Actors Guild activist Karen Morley, and some of the most adventurous animators in town. Only a few of the artists actually received a salary. Most held day jobs at unionized cartoon companies, and jammed into a cramped animation studio at night to volunteer their unique skills to the labor movement’s election effort.

Hell Bent for Election debuted at the UAW convention in August 1944. The CIO-PAC reproduced thousands of sixteen-millimeter film copies and dispatched them to union hall screenings across the country. It also played, in this pre-TV era, in community centers, schools, living rooms—wherever CIO members could organize a crowd.

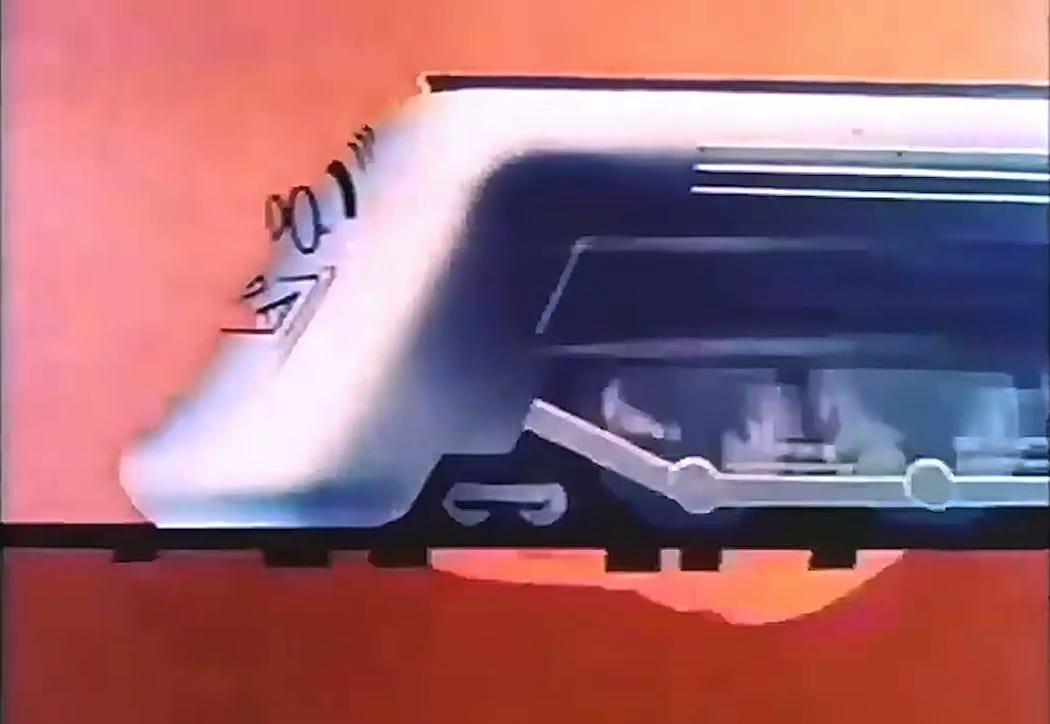

The thirteen-minute film centers on Joe the Worker. He must make sure he throws the railroad switch at the right moment to allow the ‘Win the War Special’ (a sleek modern train with Roosevelt’s jaunty face on the front of the engine) to pass, while forcing the Defeatist Limited (a creaky coal-fired steam locomotive with a caboose labeled ‘Jim Crow’) to remain behind on a sidetrack. The station master, who closely resembles Uncle Sam, warns Joe, “Don’t fall asleep at the switch again, Joe, like you did in 1942!”

When the key moment arrives, Joe succeeds, but not before a difficult struggle with a reactionary southern politician, who mouths employer platitudes and seeks to distract Joe from his task. He so enrages Joe with his anti-union diatribes and efforts to derail the Win the War Special that Joe can’t help himself: he raises his fist to deliver a well-deserved punch in the conservative politician’s face. The narrator’s voice calls out urgently, “Wait, Joe! There’s a better way.” Joe’s fist suddenly holds a voting stamp, and he slams it down on a ballot.

No single image better captures the desire of the CIO leadership during the war to keep rank and file anger and attention focused on an electoral solution to their problems and away from direct workplace action.

This took some doing. Pressured by speedup and long hours, and despite no-strike pledges by AFL and CIO, workers sporadically walked off the job throughout the war. From fewer than a million workers on strike in 1942, work stoppages—most of them unofficial, or ‘wildcat’ strikes—increased steadily, involving over three million workers in 1945.

What the post war world should look like was spelled out at the end of Hell Bent for Election. After the ‘Win the War Special’ had triumphed over the ‘Defeatist Limited,’ the closing sequences of the cartoon featured a catchy song accompanying images of future post-war prosperity, guaranteed by government social insurance programs and a robust economy:

There’ll be a job for everyone, everyone, everyone,

There’ll be a job for everyone if we get out and vote.

The CIO’s vision of full employment, high wages and industrial democracy through collaboration among business, labor and government—the “People’s Program”—seemed like a natural extension of the cooperative successes of the war years. Together with a strong union get-out-the-vote effort, Hell Bent for Election helped push Roosevelt over the top in 1944 and allowed the Democrats to enlarge their majorities in congress.

Fred Glass is the author of From Mission to Microchip: A History of the California Labor Movement (UC Press, 2016) and a former member of the State Committee of California DSA