Arsenal of Democracy: Fighting Racism in Bay Area Shipyards During WW II

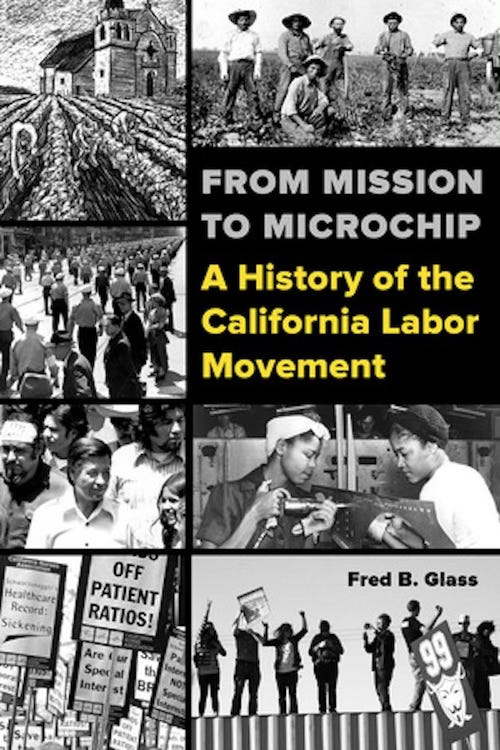

The Labor History Corner--an excerpt from From Mission to Microchip: A History of the California Labor Movement By Fred Glass

A version of this article appeared on the California Labor Federation California Labor History website. You can buy From Mission to Microchip: A History of the California Labor Movement from the University of California Press.

World War II lifted California out of the Great Depression. In 1940, the jobless ranks were down from their peak in the early 1930s, but still lingered at an unacceptable 12%. By 1944, unemployment had fallen to less than 1%—effectively non-existent for anyone who wanted a job, though the working population of the state had increased by two fifths over pre-war levels.

Between 1940 and 1945, the federal government spent over $16 billion on major war production contracts in California. The jobs created by these public expenditures in mostly private defense industries inspired the migration of a half million white workers and their families from the southwest, and a third of a million African Americans from the south. Women, too, were heavily recruited to industrial work, previously a male domain. Remaking California as an “arsenal of democracy” enabled workplaces to undergo rapid conversion to generate different products. The war—yet another of the state’s periodic “gold rushes”—reconstructed the California economy and recomposed its working class.

Manufacturing employment increased from a third of a million workers before the war to 900,000 by 1943. Eighty per cent of this growth went into shipbuilding and aircraft production. The shipyards were concentrated around San Francisco Bay, although a few large facilities came online in southern California.

“To break a union is to break yourself”

To overcome production bottlenecks and reduce transportation costs for the steel necessary to manufacture ships and planes, capitalist Henry Kaiser partnered with New Deal officials to finance the first integrated steel facility on the west coast capable of competing with Eastern and Midwestern producers. Kaiser Steel, employing five thousand workers, opened in Fontana, previously known for citrus orchards and chicken ranching, sixty miles northeast of Los Angeles, in 1942. Kaiser stated his support for collective bargaining in unusually strong terms: “To break a union is to break yourself.”

Next to the war, work and working people were at the center of the public eye. Without maximum productivity on the home front, the armed forces could not be properly supplied. The fierce battles between labor and capital of the previous decade had to be set aside. Other sources of social unrest, such as racial discrimination, had to be overcome in the interests of the war effort. Everyone agreed with the overriding importance of the war. But that surface consensus faced some tests.

Building ships

Before the war, shipbuilding and repair, traditionally part of the Bay Area economy, employed six thousand workers, mostly members of craft unions belonging to the Metal Trades Council. Within a few years San Francisco, along with nearby communities, became the greatest builder of ships in history. More than 240,000 people, working at union wages around the clock in three shifts, poured hundreds of Liberty Ships, tankers, and other military vessels onto the water from yards ringing the Bay.

This did not represent an expansion of craft labor. To meet the demands of the war, the owners and managers of the four new enormous Kaiser shipyards in Richmond innovated assembly line production techniques to turn out ships more quickly. Traditional yards were forced to rethink and renovate their existing facilities and work methods.

Since the great majority of war workers had never built a ship before, and the immediate goal was to build ships faster than German and Japanese submarines could sink them, a four-year apprenticeship was out of the question. Instead, a specialized division of labor, with continuous training for new recruits, replaced the former all-around craft worker with semi-skilled industrial laborers, each trained to perform a handful of defined assembly tasks.

About a quarter of the workers were women. Around ten per cent were African American. A fifth were “Okies,” many of whom seized the opportunity to escape their failed dreams of becoming Central Valley farmers.

Reaction

The reaction to the newcomers by the older, skilled white AFL craftsmen ranged from a resigned acceptance that everyone’s help was necessary to win the war, to hostility and fear that their hard-won collective bargaining conditions would be eroded—by the new industrial production methods, the newcomers’ ignorance of unionism, or both. Most white workers recruited from the south brought deep racial prejudices with them. Tensions in the workforce, based in clashing cultures, assumptions, and traditions, needed continuous attention to ensure smooth production.

The largest shipbuilding union was the International Brotherhood of Boilermakers. The Boilermakers union was also the dominant force within the AFL Metal Trades Council, which negotiated the closed shop collective bargaining agreement with west coast shipyard employers that governed wages, hiring and promotion.

Some AFL unions in the yards were interracial, such as Shipyard Laborers Local 886, which employed Jamaican-born Harry Lumsden as a union staffer. But the Boilermakers, by far the largest union, refused to admit African Americans. When the employers discriminated, the Boilermakers Union was not just disinterested; the union acted as badly as the employers.

Pervasive employment discrimination

These problems were not unique to Bay Area shipyards. As a result of pervasive employment discrimination in the new war industries, African American union leaders A. Philip Randolph and Oakland’s C. L. Dellums of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters approached President Roosevelt and requested he take action. When he declined, they threatened to call a march on Washington to demand fair employment practices. Eyeing the potential for an international embarrassment during the war to defend freedom and democracy, Roosevelt agreed to issue Executive Order 8802 in June 1941, declaring no employer receiving federal funding for defense contracts could discriminate. 8802 established a federal Fair Employment Practices Commission (FEPC) for the war’s duration, with modest enforcement powers and staff, to oversee implementation of the executive order.

Nonetheless, progress was slow, nowhere slower than in Bay Area shipyards. To obey the letter of the law, the Boilermakers issued employment clearances for black workers while continuing to keep them out of the union. With the assistance of the FEPC, Berkeley native Frances Mary Albrier forced the Boilermakers to clear her for a Kaiser welder’s job, and to accept her dues payment to the union. Instead of being given full membership, she was shunted to a segregated auxiliary local the union set up in Oakland’s Moore shipyard.

Soon the Boilermakers created three Bay Area auxiliaries with thousands of members. The members of these auxiliaries had no right to vote for officers in the “real” locals to which they were affiliated, nor on much else. The Boilermakers national executive board had the power to remove local officers and run locals directly, and used that power freely. The shipyards’ African American workers, most of whom had never been in a union, were rightfully distrustful of the second class organizations they found themselves saddled with.

In response to the discriminatory behavior they faced from employers and unions alike, black shipyard workers developed various strategies, including lawsuits, job actions and organizing community support. The East Bay Shipyard Workers Committee, led by Ray Thompson, a Communist working at Moore, at first counseled blacks to join auxiliaries, pay dues, and fight the Boilermakers’ racist practices from within the union. Later it called for a dues boycott.

Blunt instruments, but a place to stand

In this process the auxiliaries played a dual role. They were blunt instruments, unions without many of the weapons workers needed and used; they were part of the problem. But with access, albeit sharply limited, to treasuries, and a place to stand, they provided the possibility for communication and organizing among workers, and between workers and the community.

In San Francisco, the small but active African American community in the multi-racial Fillmore district swelled with migrants seeking jobs in the shipyards. One recent arrival soon landed at the center of black community aspirations for a better life. Joseph James went to work as a welder at Marinship in 1942, contributing his professional vocal talents to ship launching ceremonies in the yard. He became active in the San Francisco NAACP, and served on Marinship’s Negro Advisory Board, which helped put out a special issue of the yard’s newsletter devoted to racial issues.

Despite his willingness to partner with official Marinship activities, James drew the line at the Boilermakers’ exclusionary policies. Along with hundreds of other black Marinship workers, James refused to pay dues to Auxiliary A-41, which he called “a Jim Crow fake union.” In November 1943, when the Boilermakers told the company to fire the non-dues payers, James and most of the eleven hundred black workers, supported by the San Francisco Committee Against Segregation and Discrimination (SFCASD), staged a public demonstration in front of Marinship during a shift change.

Strike

James and 150 other workers were fired. Hundreds of workers stayed off the job in protest, their standoff drawing national attention. Pressures on the company to rehire the workers or reach an understanding that allowed them to stay came from the African American community and from government officials.

The strike lasted a week. The SFCASD, assisted by Dellums, filed suit on behalf of James and other workers, calling for their reinstatement and fines against the union. An injunction put the workers back on the job, but the legal battle grinded on throughout the rest of the war.

Skirmishes broke out on other fronts. The FEPC ordered the Boilermakers and shipyard employers to cease discriminating; the union and companies appealed. In February 1944 the Marin Court decided James vs. Marinship against the Boilermakers union: the union could no longer force workers into auxiliaries, and the company could not fire anyone for refusing to pay dues to the segregated unions. The decision was affirmed a year later by the California Supreme Court.

The legal victory came too late, however, to have the impact hoped for by the plaintiffs. By 1945, anticipating the end of the war, the government stopped its orders for ships. The shipyards cut back production and laid off workers. Marinship closed in May 1946. At that point only 600 workers remained from 20,000 at the peak of war production. Joseph James left San Francisco and went back to New York, resuming his former career as an opera baritone. In 1948 the boilermakers union in the Bay Area’s shipyards was integrated, but that meant jobs for just 150 black workers.

Fred Glass is the author of From Mission to Microchip: A History of the California Labor Movement (UC Press, 2016) and a former member of the State Committee of California DSA

Stay tuned for the next installment…