By Mel Freilicher

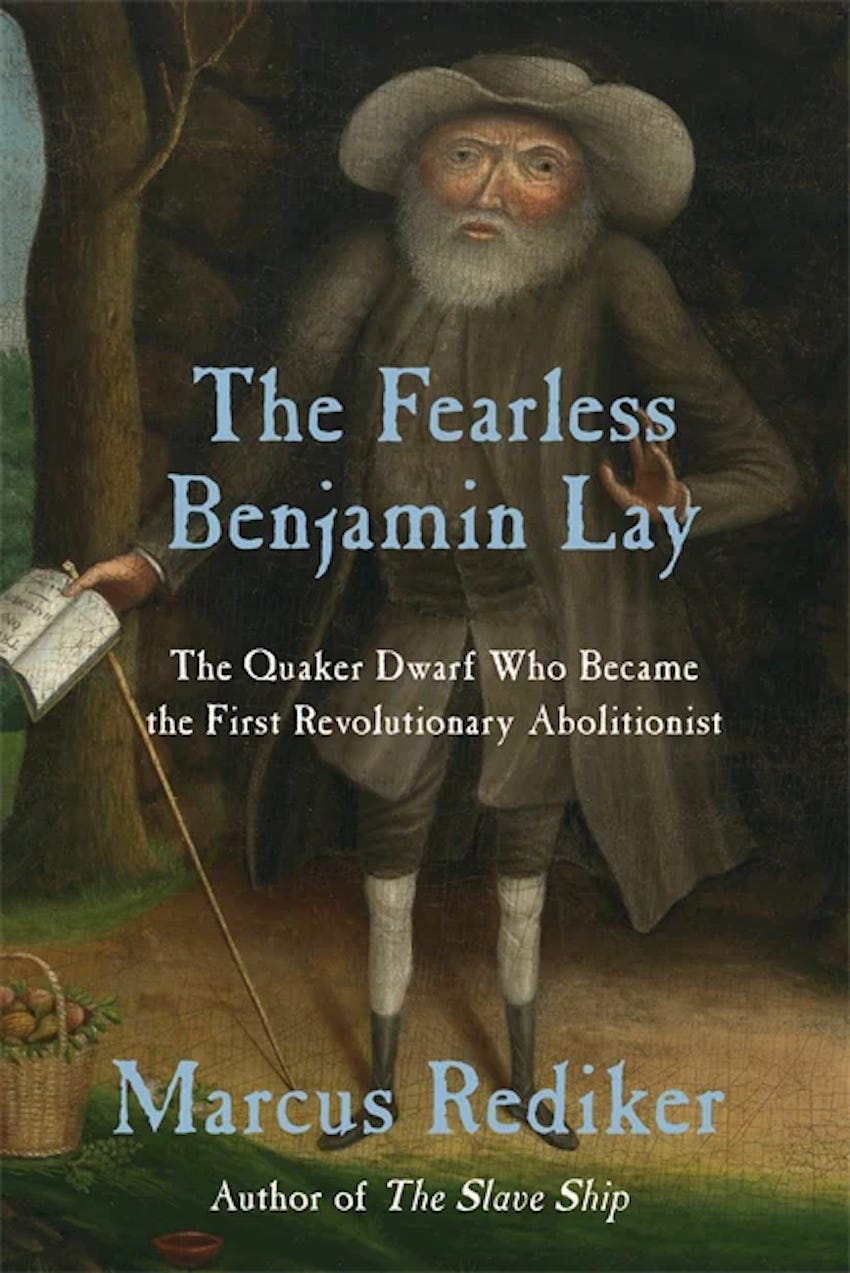

The Fearless Benjamin Lay: The Quaker Dwarf Who Became the First Revolutionary Abolitionist by Marcus Rediker on Beacon Books, 2017.

Benjamin Lay was fierce. Determined to shame and expose slave-owning Quakers, especially in Pennsylvania where he and his wife, Sarah, migrated from their native England. In 1738, he “strode into a large gathering of Quakers” at the Burlington, New Jersey meeting house for their biggest event, the Philadelphia Yearly Meeting. Having journeyed almost 30 miles on foot, he’d arrived 4 days earlier and subsisted on “Acorns & peaches.”

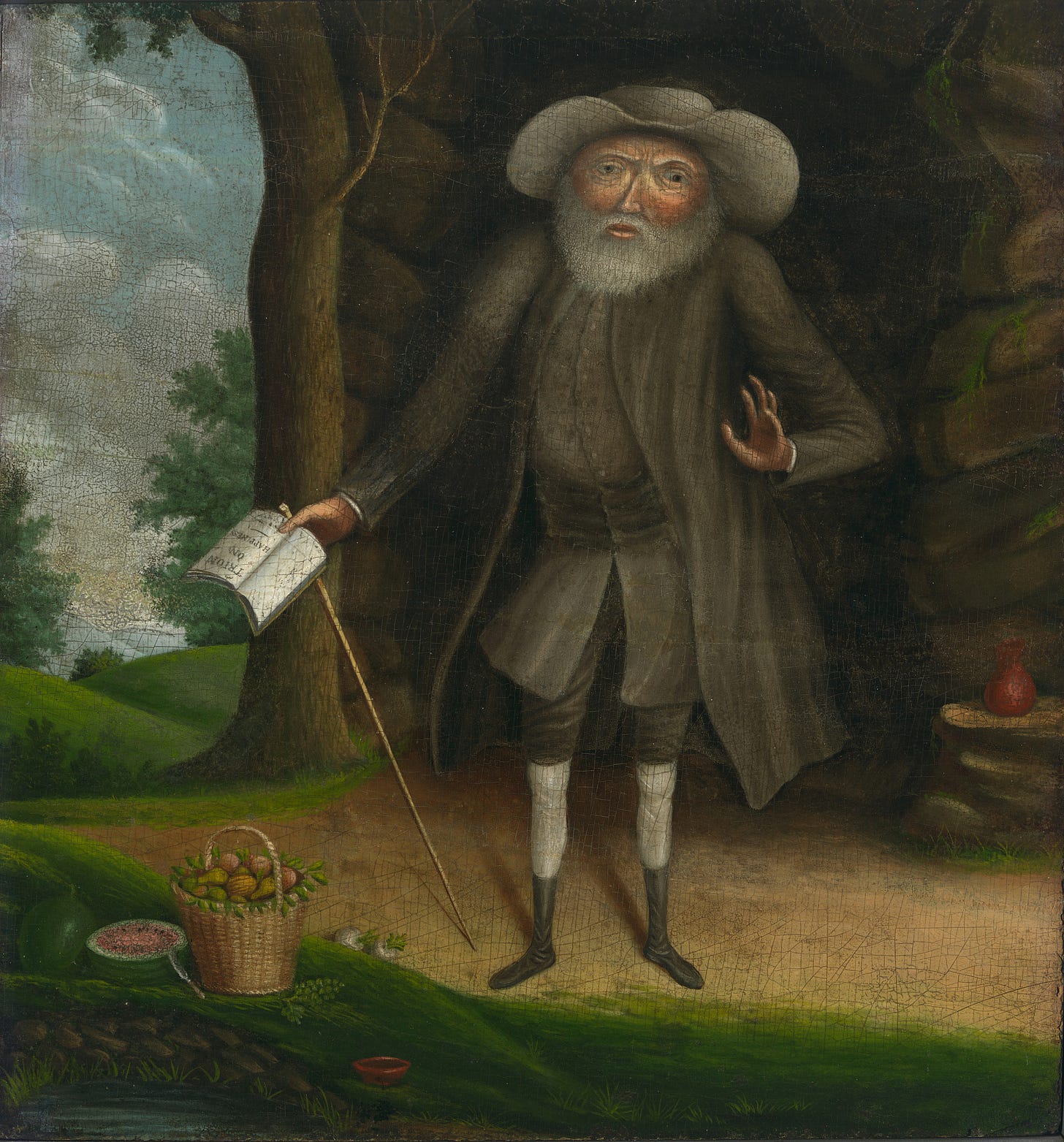

Sitting in a conspicuous location, Benjamin wore a great coat which hid a military uniform underneath, and a sword from fellow Quakers who, back in 1660, had embraced a “peace testimony,” refusing all weapons and warfare. Also concealed was a hollowed-out book with a secret compartment into which he’d tucked a tied-off animal bladder filled with bright red pokeberry juice. Finally, Benjamin rose to address this gathering of “Mighty Quakers”: many had grown rich on Atlantic commerce and bought human property.

In a booming voice, Lay announced God Almighty respects all people equally, rich and poor, men and women, white people and black people alike. Throwing off his great coat to reveal the military uniform beneath, he thundered his judgment: “Thus shall God shed the blood of those persons who enslave fellow creatures.” Raising the book above his head, he plunged the sword through it. “To the shock of all, he splattered ‘blood’ on the heads and bodies of slave keepers”; several women swooned.

A repetition of similar “bladder-of-blood” spectacles in England, this performance was one among many instances of Lay’s guerilla theater. Refusing to be cowed by the rich and powerful, everywhere he went, Benjamin visited a variety of churches, ranting at ministers he disliked. If an ungodly minister owned slaves, which was not uncommon in Philadelphia, “Benjamin doubled his wrath.”

In each instance, his fellow Quakers removed Lay by force as a “trouble-maker” or “disorderly person.” On one occasion, after he was tossed into the street on a rainy day, Benjamin returned to the main door of the meetinghouse, lay down in the mud, and required every person leaving the meeting to step over his supine body.

Once, using a recent, deep snowfall, he positioned himself at a gateway to a Quaker meeting house outside of Philadelphia. Placing “his right leg and foot entirely uncovered” in the snow, like the ancient philosopher Diogenes who walked barefoot in snow. When one Quaker after another expressed concern, urging Benjamin to shelter against the freezing cold, he replied, “Ah, you pretend compassion for me, but you do not feel for the poor slaves in your fields, who go all winter half clad.” Citing biblical verse, he ended with “So saith Benjamin the prophet.”

Beginning to stage his theater of apocalyptic outrage in public venues, including city streets and markets, Benjamin arranged a table in the open-air market of Philadelphia, with a set of fine china teacups and saucers. (Apparently, they’d belonged to his wife who died seven years earlier.) As a crowd gathered, Benjamin took out a hammer and began smashing the set to protest the mistreatment of those who harvested the tea in in Asia and those who produced the sugar in the Americas.

The crowd was shocked, with some screaming Benjamin shouldn’t destroy the beautiful teacups—Give them to me! Others offered to buy them. Benjamin’s iconoclastic attitude toward fine private property caused pandemonium to erupt, Rediker reports. A growing mob finally rushed him and threw him to the ground. A “stout youth,” lifting Benjamin over his head, carried him off. The lad’s mates then “saved the balance of the tea-set from destruction and carry’d off as much of it as they could get.”

In the Preface to the paperback edition of The Fearless Benjamin Lay, the author describes Benjamin as a “brave and inimitable antislavery activist, who as one of the best known people of his time, had been almost completely erased from popular memory…but at long last he’s beginning to get the attention he deserves.”

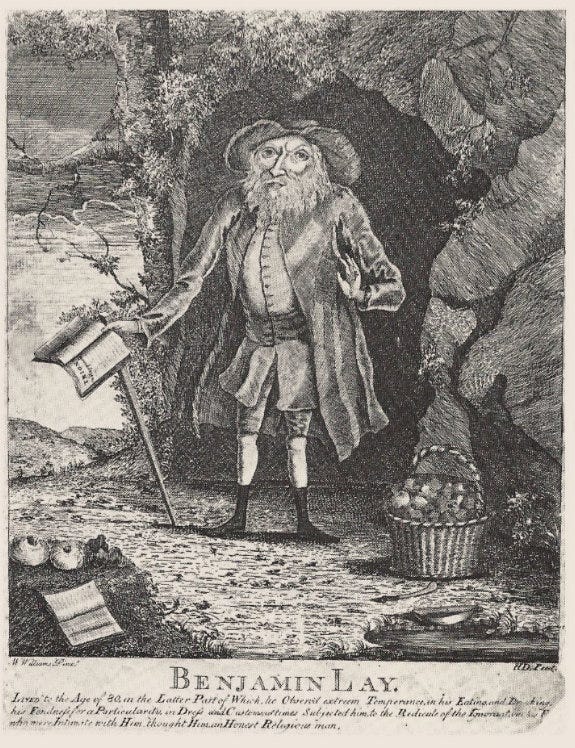

A hunchbacked dwarf, self-described as “not much above four feet,” Benjamin was the frequent object of ridicule, and scorn. As was his wife, Sarah, also a little person, a hunchback—and a principled, well respected Quaker, a (less volatile) abolitionist in her own right.

“First and foremost an antinomian radical,” Lay believed salvation could be obtained by grace alone “and a direct connection to God placed the believer above man-made law.” As heresiographer [yes, it’s a word, to my surprise!] Ephraim Pagett wrote, “The Antinomians are so-called…because they would have the Law abolished.” Offering a deep critique of power—against institutions, the state, and “all outward forms”—the conscience reigned supreme. “Benjamin was, in short, a free spirit.”

In his native Colchester in the rural county of Essex, and in London, Benjamin was chiefly incensed by the insincerity, pomposity, and vanity of many Quaker elders. Further, he combined radical ideas and practices for his time, rarely thought of as related: vegetarianism, animal rights, opposition to the death penalty, environmentalism, and the politics of consumption. For the last third of his life, he lived in a cave outside Philadelphia-- cultivating his own food, and making his own clothes.

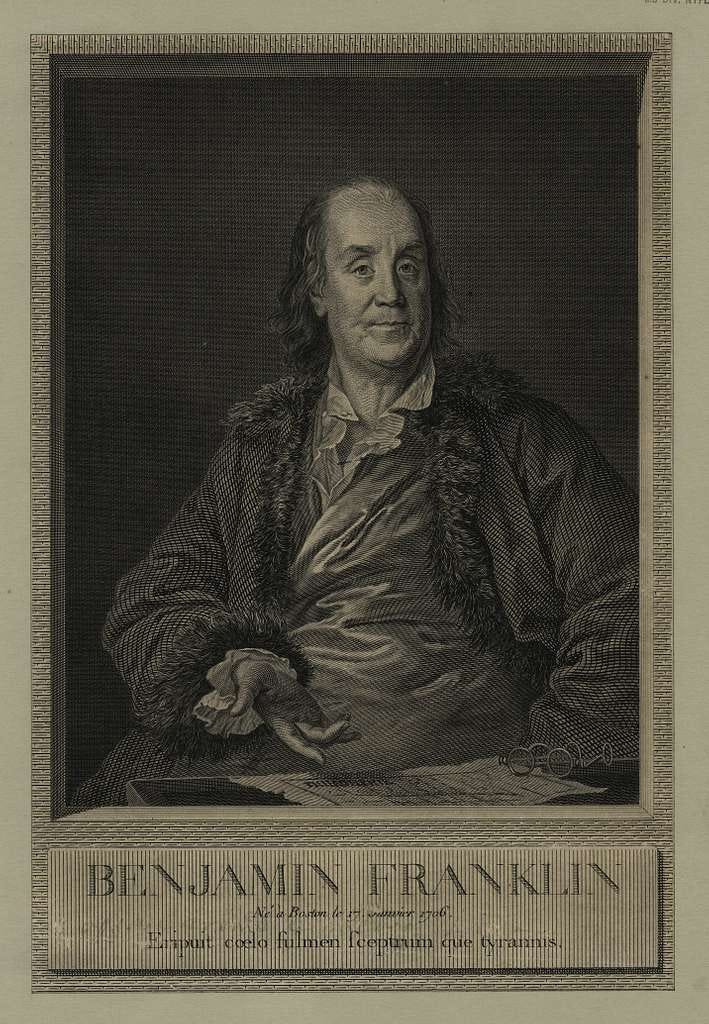

Embracing self-denial and temperance, like his friend Benjamin Franklin, and dressed in simple, undyed clothes, Benjamin was a Christian ascetic [but not too ascetic, I was glad to read]. “Selecting a spot near a fine spring of water,” he erected a cottage into a “natural excavation in the earth…to afford himself a commodious apartment.” Lining the entrance with stone, he created a roof with sprigs of evergreen. Outside, he cultivated potatoes, squash, radishes, and melons, planted apple, peach and walnut trees, and tended a massive bee colony, some hundred feet long.

The rather spacious interior of the cave had room for a spinning jenny, and a large library. An autodidact and voracious reader, on and off for much of his life Benjamin worked as a book dealer. Possessing the fullest collection of early Quaker writings to be found in Pennsylvania, he participated in the print culture of the city: joining newspaper debates, subscribing to the Pennsylvania Gazette, and spending much time in Benjamin Franklin’s print shop, where he sometimes raised subscriptions to publish books he admired.

Benjamin took an active role in the infamous case of John Peter Zenger, a printer and journalist for New York Weekly Journal who penned a critical article on that state’s corrupt governor: promptly suing Zenger for libel, he locked him up for 8 months in 1733-34. Benjamin Franklin republished an article from a London periodical--a ringing defense of Zenger; Lay’s immediate response to a published rebuttal was particularly virulent in defense of the distinguished Philadelphia attorney who successfully won the Zenger case: establishing a crucial legal milestone and precedent for an independent press.

Naturally, Benjamin had his own concerns about censorship and free expression. The Quaker Board of Overseers in Pennsylvania was busy denying publication to all critics of slavery. They would have rejected the book Benjamin was then working on. (When Franklin published it, he left off any information about the printer.)

Needless to say, wealthy Quaker ministers were often trying to get rid of Lay, who believed they were destroying his religion. Constantly battling, he was “disowned” from various congregations in England, and the U.S. on at least four separate occasions. Although everybody was welcome to worship, the “disowned” were shut out of any business or official meetings, and had no say in church policy decisions. [Reading about this now, some of it seems rather comic. For instance…]

In Colchester where he’d grown up, several elders of one congregation asked Benjamin to attend a meeting to discuss his “disorderly and irregular practices.” When he refused, an official announcement stated because of these “evil practices tending to Confusions…we can have no Unity with him until he has given ye Friends of ye Monthly Meeting…Satisfaction.”

Essentially a second disownment, technically this declaration wouldn’t count because Lay had yet to be reinstated at Devonshire House before he could be officially disowned again. There he’d spoken out against the minister while he was preaching; after the meeting, insisting to several congregants, the man was “a Drunkard and a swine.” Adding, “drunk with wind,” and preaching “in his own spirit and not from the spirit of Truth.”

Elders in Colchester drew up a new list of “gross & Abominable Practices,” which they planned to read aloud at the next meeting Benjamin attended. He escalated the conflict by speaking from the women’s section of the Great Meeting House (Quakers were then debating whether men and women should worship separately). The outraged leadership took another unprecedented step, appointing three men (including the official grave digger), as an internal police force, “to keep him out of ye Gallery for ye future.”

The pacifists were now ready to use physical force to prevent Benjamin’s protests, Rediker comments. But both Benjamin and Sarah loved their fellow Quakers, and continued to seek out more congenial meeting houses while fighting about issues of hierarchy and power. Additional complications: to marry within the church, and later to immigrate to Pennsylvania as Quakers in good standing, the Lays had to engage in calculated strategical maneuvering.

Even though Sarah Smith, who’d converted to Quakerism “in her young years,” had earned so much respect from the Quaker community to be designated an “approved minister,” traveling far and wide to represent the local congregation, Benjamin’s initial petition to marry her was denied. Having recently offended still more elders—claiming they spoke with “Noise of Words, and oftentimes no Sense”—Benjamin was told to apologize before he could be reinstated in the church. His grudging apology--of the “sorry you were offended” kind--was not accepted.

Whatever their complaints about him, Benjamin insisted these leaders had no right to withhold the marriage certificate, and went over their heads with an appeal directly to the London Quarterly Meeting. Appointing ten Friends from all over the city to examine the matter, and interview all parties, their report stated: “Wee absolutely disapprove of Benj Lays behaviour in his open opposition to some Publicke Friends”--ending with they ought to give Benjamin the marriage certificate. Benjamin and Sarah were married July 10, 1718.

Tensions within the local meeting lingered. Two months later, he and Sarah set sail for Barbados, “the world’s leading slave society, the crown jewel of the British empire tiara,” as Rediker puts it. The combination of 9,000 people of European descent and more than 70,000 Africans added up to “the worst scene of all quarrels and contentious pride and poverty drunkenness debauchery.”

The Lays set up a small shop on the docks in Barbados which Benjamin had visited when he was a sailor: so they became eye-witnesses to many gruesome atrocities. Seeing enslaved people so weak they fainted and collapsed in the street, Benjamin lamented: “Many are Murthered by Working hard, and Starving, Whipping, Racking, Hanging, Burning, Scalding, Roasting, and other Hellish Torments.”

In the industrialized production of sugar, slaves were mangled, sheared-off body parts fell into boiling vats, and sugar itself ended up containing “Limbs, Bowels, and excrements.” Long before anyone campaigned against the extreme violence of plantation production, Benjamin knew “sugar was made with blood.”

Benjamin’s knowledge of slavery had begun as a sailor, listening to “four Men that had been 17 Years Slaves in Turky.” He heard accounts of rape in the infamous Middle Passage— “the Captain [kept] 6 or10 of them [female slaves] in the Cabbin, and the Sailors as many as they pleased.” He also understood in Africa the trade tended to the “Destruction and Ruin of the whole Country.” The 4 men enslaved in Turkey, Benjamin concluded, were not as “badly used” by Muslims as “the poor Negroes are by some called Christians.”

On one occasion, visiting a fellow Quaker, Sarah was startled to encounter a stark naked slave suspended in the air, probably by chains: his “trembling and shivering” body lay in a “Pool of Blood.” Sarah went back inside, begging the Friend to explain: not only did he show no remorse, but railed against the man who had dared to run away for “a day or two.”

The Lays began to hold meetings and serve meals at their home, which drew ever larger crowds of enslaved people, often in defiance of their masters. Eventually “many hundreds” turned up, creating a public spectacle. At these gatherings the host and hostess denounced slavery, drawing the wrath of the island’s ruling class who began to “clamour” against the Lays, seeking to banish them for their subversive fraternization with slaves.

In truth, Benjamin and Sarah had already decided to leave. After 18 months, they returned to London, “but the look of death in Barbados had transformed them. Benjamin would remain haunted—one might say tormented—for the rest of his life by his encounter with slavery.” Years later, he remembered this period as a turning point when he converted to abolitionist principles.

By the time Benjamin reached his early thirties, he was “a working man of the world,” Rediker asserts. “He’d known pastoral labor, sheepherding, the urban crafts as a glover…and had survived rigorous proletarian work at sea as a ‘common sailor.’” He’d lived in a small village, a manufacturing town, an imperial metropolis, and on big ships on the oceans and in ports around the world.

Arriving in Philadelphia in 1732, he could indulge his lifelong passion, and set himself up as a bookseller. To get started, he’d brought over with him “a large parcel of valuable Books,” especially of Quaker history, unspecified histories of England and the world, “large and small Bibles, Testaments, Psalters, Primmers, Hornbooks.” Also multiple school books, especially on mathematics and astronomy, and classical authors such as Seneca.

Philadelphia was then North America’s largest city with 12,000 residents, containing the world’s second largest Quaker community. Featuring a well-ordered grid of streets, amid dynamic marketplaces, two thousand houses, many of them handsomely made of brick and 3 stories high. Founded in 1682 as a “peaceable kingdom,” the Quaker colony, a place without war, was based on principles of fair treatment of all peoples and religions, including the indigenous Lenni Lenape Indians.

Quakerism itself had begun as a proto-evangelical Christian movement during the English Revolution. As armies warred and censorship broke down, “a motley crew of uppity commoners” dared to use the quarrel between Royalists and Roundheads to try to establish an anticlerical, godly republic, and advance the principles of democracy and equality: believing to the pure of heart, all things were pure.

To attack the Church of England, Protestant radicals such as Levellers (a populist group, advocating equality before the law, popular sovereignty, religious tolerance), the Diggers (supporting common ownership of property), Seekers, Ranters were basically amalgamated into the national Quaker movement of the 1650s. Its early leaders, like George Fox, were as militant as Benjamin Lay became later. He felt an affinity with the ultra-antinomian Ranters, railing against “hireling ministers” who “preached their bellies.”

In Philadelphia, Benjamin kept his connection with the waterfront--befriending a Captain and a “ship-keeper,” an overseer of the docks. He attended various meeting houses around the city. Rediker describes 4 of the wealthiest merchants in town: “weighty Quakers” leading the religious and political life of the city and colony. Slaveholders, all three, and probably all 4. More than half the members of the Philadelphia Monthly Meeting owned slaves.

The newly arrived emigre found it “intolerable” that some of these slave keepers had come to America as “vile servants,” experienced the hard life of indentured servitude, gained their freedom, acquired wealth, and now mistreated their own slaves. Worse, they would perpetuate this inequality by leaving the enslaved as property to “proud, Dainty, Lazy, Scornful, Tyrannical and often beggarly Children for them to Dominate and Tyrannize over.”

The trauma Benjamin had suffered in Barbados was “deeply and disturbingly reactivated, abolitionist principles reengaged…not least because he’d had such high hopes for his new godly community of Friends.” To be sure, bondage in his new home was fundamentally different from what he’d witnessed ten years earlier in Barbados. Only one in ten persons were enslaved, compared to almost nine in ten on the island. Levels of violence and repression were considerably lower. Another difference: the Lays landed amidst an explosive cycle of rebellion.

Between 1730 and 1742 unfree workers (including Irish indentured servants) organized more than 80 conspiracies, insurrections, and mass runaways—six or seven times more than in the dozen years before that: affecting British, French, Dutch and Danish colonies in the Caribbean and throughout the Americas, from Bermuda to New Orleans, from Guyana to New York. Maroon wars [fought jointly by runaway slaves who’d made it to indigenous communities] in Jamaica and Suriname “gave hope to rebels everywhere.”

The causes of this cycle of rebellion are not entirely clear, but Rediker assesses two developments stand out. First, the 1730s witnessed an overproduction crisis in the sugar industry, causing prices to plummet and conditions on plantations to deteriorate. Second, many thousands of trained warriors on the Gold Coast of Africa had been enslaved and shipped to the Americas, where they played leading roles in the conspiracies and insurrections. Benjamin’s message: “the sword would be sheathed in the bowels of the nation, if they did not leave off oppressing the negroes.”

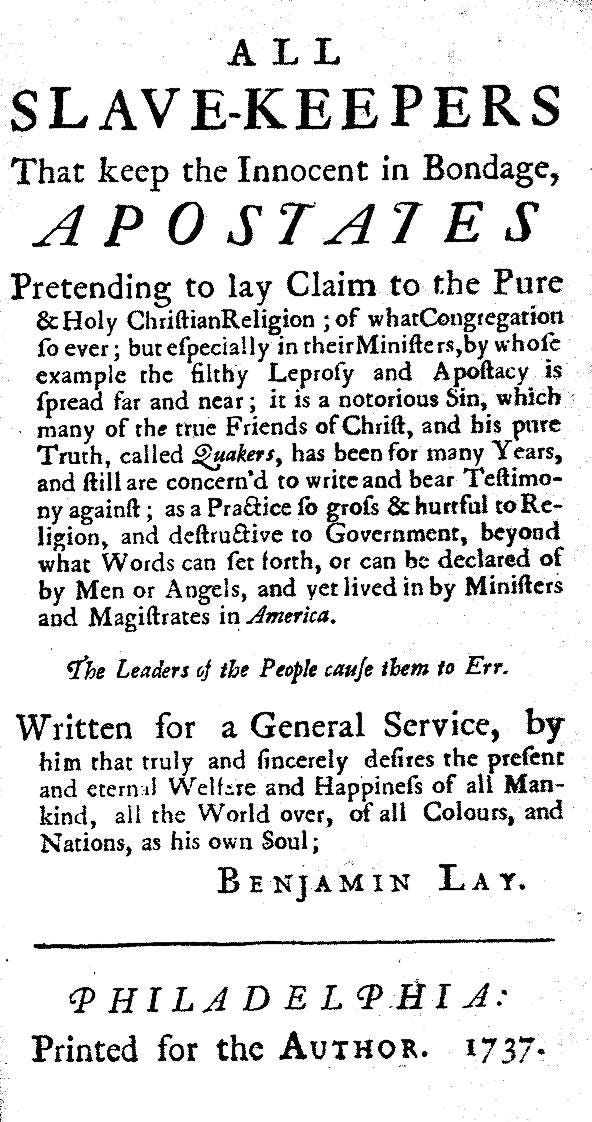

Beginning six months after Sarah’s death (they had 17 years together), and for the following two years, Benjamin spent much of his time writing All Slave-keepers That Keep the Innocent in Bondage, Apostates, published by Benjamin Franklin in 1738. At a time when slavery seemed a normal, indeed unchangeable foundation of many societies, “the book represented an important advance: demanding an immediate, unconditional abolition of bondage.”

A first-time author, Benjamin knew the book had shortcomings: apologizing repeatedly for many “digressions” in the narrative—pointing out he had almost no formal education. Much of his learning was self-acquired: probably largely at sea where literate sailors often taught others during slack periods.

Paying little attention to genre, he told Benjamin Franklin “to print any part thou pleaseth first” (which he certainly did). Given to a stream-of-consciousness flow of words and ideas, based on what Quakers called “openings” of the spirit, the only form Lay seemed to have in mind was “the tried and true early modern commonplace book--a personal, popular, usually unpublished kind of writing distinct from a journal or diary.”

Benjamin’s many entries over the 277 pages of his book were highly eclectic: including Biblical passages, pieces of autobiography, personal reflections, letters he wrote to friends, notes on history, summaries of and observations about books he’d read [Book report!], and most importantly, arguments against false ministers and slavery, especially as those two themes reflected his own struggles within the community.

“Even as Benjamin openly professed his limitations,” Rediker insists, “he demonstrated rhetorical skills as he made the arguments. He wrote the book as he spoke—from the heart, in an intimate voice.” It reads like speech written down: often using humor and sarcasm to make his points. Putting words in the mouth of a hypocritical Quaker slave owner, for instance: “Negro, fetch my best Gelding quickly, for me to ride to Meeting: to preach the Gospel of Glad Tydings to all men…and opening the Prison-Doors to them that are bound; but I’ll keep thee in Bondage nevertheless, help thyself if thee can.”

On several occasions, Benjamin “resorts to a kind of ventriloquism,” recording the voices of enslaved Africans in the pidgin language of Barbados. This technique became common later, in both racist and antiracist writings, “but very few writers had listened closely enough to transcribe the sounds of African diasporic speech in 1738.”

Historian Rosemary Moore offers a global truth about Quakerism: after 1660, its oral culture was always more radical than its print culture, carefully vetted for any deviations from orthodoxy. Benjamin’s critiques make it possible to reconstruct part of the serious debate among Quakers at the time when very little of the dispute was written down elsewhere or published.

In an effort to educate his readers, particularly the younger ones, who he regarded as ignorant of both fundamental facts and divine teaching on the subject, Benjamin laid out a series of arguments against “the greatest Sin in the World.” Henceforth, no one could claim ignorance, least of all Quakers, aspiring to live in the Light, without and within.

Benjamin had two contradictory modes for writing about slavery. Recounting the local opposition among Quakers, and even to some extent among non-Quakers, he wrote as if he were part of a small but growing movement to abolish the evil institution. In fact by the 1730s, such a group had established a core set of arguments against slavery.

His other angle: addressing the origins and morality of slavery, the author tended to speak as a prophet someone battling massive forces of evil; a solitary, courageous individual speaking truth to power. (His favorite prophet is Isaiah.) Benjamin’s “originality lay in his utterly uncompromising attitude: slavery is not just a sin, it’s ‘a soul sin’… an atrocious crime.” Lay’s work is liberally slathered with quotes from the Book of Revelations (the novice author also tended toward Hieronymus Bosch, Rediker comments).

Slave traders, he insisted, were outright murderers. Slave owning ministers committed a “double crime” against the enslaved and against their congregation: it followed that slave traders and keepers were not merely transgressors against God, they were enemies of the social order, and therefore could be subject to prosecution. He demanded all persons involved with the practice in any way be stripped of both religious and political power--including many wealthy Quakers serving in the Pennsylvania Assembly.

“Benjamin directly attacked ruling-class power.” On one occasion, his critique of wealth suggested slavery and violence were central to private property: identifying the impulse to material acquisition in “the covetous,” as a “mighty, mighty, Almost Almighty Monster, the chiefest of the Seven Devils and Supream Ruler, Head and Governor in Hell.” Lay believed “abolition must inform a revolutionary reevaluation of all life,” Rediker comments, “premised on the rejection of the capitalist values of the marketplace.”

At age 75, Lay’s health began to deteriorate. His mind remained clear and his spirit fiery, but his long travels by foot ceased. Outliving Sarah by more than two decades, Benjamin stayed home, read, continued to receive visitors in his cave, and engaged in “domestic occupations”: spun flax, tended his garden, and massive beehive.

Deciding to make a gift of a portrait of Benjamin Lay to her husband who, characteristically, was in London representing the American colonies, Deborah Read Franklin hired a painter familiar with his subject to work from memory, since Lay would have considered it vanity to pose.

One visitor, a friend and fellow Quaker sharing Benjamin’s philosophy, arrived to tell him that the 1758 Philadelphia Yearly Meeting, “after much agitation from below, initiated a process to discipline and eventually disown Quakers who traded slaves.” Slave holding was still permitted (and would be for the next 18 years) but the first step toward abolition had been taken. After a few moments’ reflection, Benjamin rose from his chair, thanked the Lord, and added, “I can now die in peace.” He died ten days later.

How did a man, who, like the “primitive Christians,” disdained worldly goods leave an estate worth $117,000 (in 2016 dollars)? Over the course of a lifetime, Rediker reminds us, Benjamin earned money as a sailor, a glover, and petty merchant—and probably never spent much of it because of his austere life. Some of his estate went to family members, however Benjamin left the bulk of his money to “poor Friends.”

Helping fellow workers—wool combers, gardeners, sawyers, thatchers, millers, and weavers--he even left money to the gravedigger in Colchester who’d thrown Benjamin out of meetings. [He who laughs last..?] More than half the named recipients were women; widows constituted the largest social group. Benjamin reserved the greatest single amount of money to be awarded (five pounds per person) to poor Quakers who wanted to be transported to America.

In the concluding chapters, Rediker states: “I seek in this book to treat Benjamin with the respect he deserves. I hope to illuminate and overcome once and for all the condescension, opposition, and isolation he received from his contemporaries and from some who have written about him since his death.” Discussion of some of the earlier bios leads to definite changes in recent years, when scholars and historians have, indeed, started treating Benjamin with the “respect he deserves.”

“How can it be that a man of such important and humane ideas is unknown today?” Rediker asks and answers: “the reasons are essentially two.” The first, Benjamin didn’t fit into the dominant, long-told “story” about the history of the abolitionist movement. Self-educated, coming from the working class, he was far from a “Gentleman Saint.” (The author quickly points out in this era, “men of education were often the supporters of slavery,” and slave masters themselves, like the “enlightened” Thomas Jefferson.)

A second reason why Benjamin is unknown: “He has long been considered deformed”—in both body and mind. As a little person and as a man thought eccentric at best and more commonly deranged or insane, “he was ridiculed and dismissed…Writers and historians marginalized him as ‘the little hunchback’ or a ‘deviant personality,’ even as they grudgingly acknowledged his contributions to the struggle against slavery.”

Eulogizing Benjamin Lay as the “keeper of the sacred flame of abolition between the years 1733 and 1753, the very years when Quaker attitudes toward slavery were changing dramatically,” Rediker asserts, “He was the most famous—and infamous—speaker and actor on the subject. He made himself central to endless discussions whether he was present or not…

The supreme agitator—ploughman, thunder, lightning. And roaring ocean all rolled into one, Benjamin confronted power fearlessly with radical demands, eventually forcing it to concede. He deserves to be remembered as a leader… the prophet whose torch of pure fire showed the way out of darkness.”

NOTE: Marcus Rediker himself is a kind of national treasure. Of his many books, I’ve only read one other, The SLAVE SHIP: A Human History: a comprehensive, exhaustive, precise and incredibly illuminating account of the history of this vehicle, entirely instrumental in perpetuating slavery. Culled from decades of study, including of multiple maritime records, Rediker examines how the physical lay-out of the ship—placement of the captain as far as possible from the mass of slaves in the galley, hierarchy of the crew’s headquarters—facilitated immense cruelty, floggings, death, suicides and massacres of slaves. Also rebellions, resistance and slave insurrections. It’s an absolutely crucial book.

Mel Freilicher retired from some four decades of teaching in UCSD's Lit. Dept./ writing program. He was publisher and co-editor of Crawl Out Your Window magazine (1974-89), a journal of the experimental literature and visual arts of the San Diego/Tijuana region. He's been writing for quite some time. He is the author of The Unmaking of Americans: 7 Lives, Encyclopedia of Rebels, American Cream, and most recently, Privilege and Power: The Novel, all on San Diego City Works Press.