By Fanny Garvey

Cold ground was my bed last night/and rock was my pillow too…

(Talking Blues, Robert Nesta “Bob” Marley)

In April 2024, the City of San Diego announced an historic plan to create a massive 1000-bed shelter in a vacant 65,000 square foot warehouse at the intersection of Kettner Boulevard and Vine Street. According to the City’s press release, the creation of this facility is an historic and monumental opportunity that will be funded through a combination of local, state and federal funds, along with significant contributions from generous local donors. Although this idea may seem historically unprecedented, it is reminiscent of a similar proposal put forth 100 years ago, in April 1924, to create a large-scale municipal lodging house with funding from city revenues and one private donor, Edwin Brown, the millionaire tramp, who had recently bought a house in Del Mar with the intention of settling permanently in San Diego.

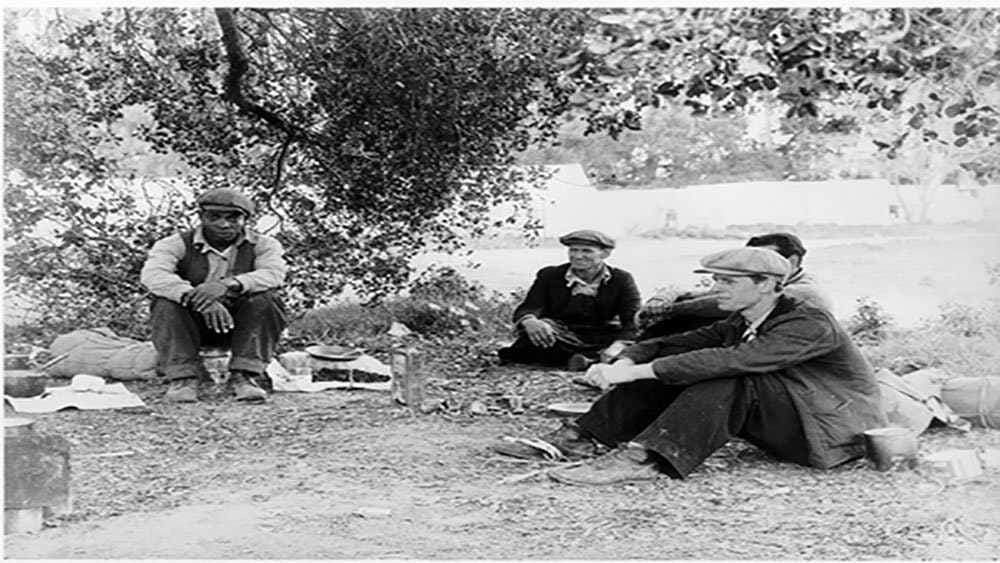

Brown was a wealthy man from Denver, Colorado who travelled throughout the United States dressed as an unemployed, unhoused person order to get at the real truth about the plight of the more than 3.5 million unemployed working people in the country. In his book, Broke, Brown described how he was frequently arrested for the crime of being broke…arrested and jailed merely because [I] had no job and very little money…homeless and moneylessness. His assessment of resources available to people who were too poor to afford a place to live seems eerily similar to contemporary conditions — hospitals overcrowded, largely with men and women brought there by exposure to unsanitary conditions and undernourishment…the average charity organisations [treating] them little better…[arresting] people for being poor is [making] them criminals.

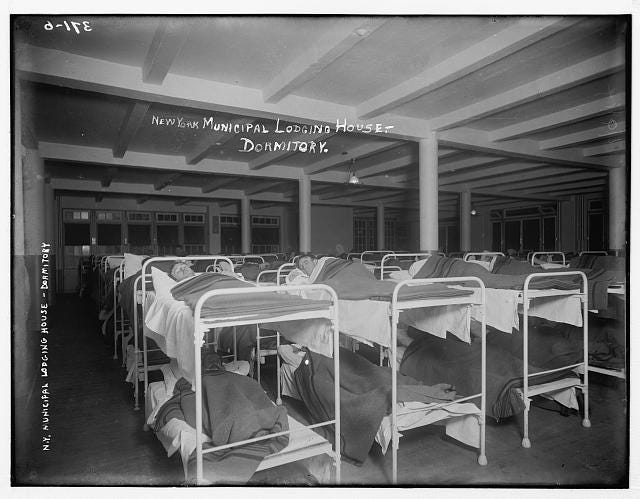

Municipal lodging houses existed in other cities and were designed to provide similar services as the mega-shelter facility being proposed now in San Diego — on-site security, meals, showers, restrooms, a commercial kitchen, laundry facilities and dining and recreation areas. One of the largest municipal lodging houses of the 1920s was in New York City, where, in 1924, the Bowery district YMCA reported there was an estimated 60,000 unhoused persons in the city, nearly twice as many as in the previous year. Finding statistics for the number of unhoused persons in San Diego in 1924 proved difficult, however, in reading newspaper articles from that year which described the treatment of the unhoused in the city revealed striking similarities to contemporary conditions. Essentially, the unhoused in 1924 struggled to survive in a city where wages were low, housing was unaffordable, and, like now, they were lumped into a class of undesirablepersons and subjected to California 1855 vagrancy laws in a manner that kept them marginalised and, as Brown observed, criminalised.

*******

Although massive poverty, unemployment and homelessness is most often associated with the Great Depression era of the 1930s, these conditions were also prevalent in the Roaring Twenties, which were acclaimed for their alleged economic prosperity. However, during the 1920s, more than 60% of the American population had incomes below the federal poverty level of $2000 per year and lived in sub-standard conditions, including tents and shacks pieced together from whatever materials they could find. Yet, these makeshift homes were rarely permanent due to the need to move from place to place, whether in search of work, or due to the use of vagrancy laws by local governments. Additionally, there was no federal, state or local assistance programs — no unemployment benefits, no welfare payments, no food stamps, no disability payments, and no medical insurance. These factors, combined with the popularity of illegal liquor and drugs during the Prohibition era, created an environment that led many people to pursue any number of avenue to secure a day’s income, including making moonshine, dealing drugs, participating in prostitution, and committing petty crimes against property, such as shoplifting and fencing stolen consumer goods. And, of course, such a harsh daily existence also led to the working poor indulging in drugs and alcohol to take the edge off their plight.

Such conditions made it nearly impossible for the poor to avoid being classified as vagrants — or vags, as contemporary San Diego newspapers dubbed them. My research discovered 233 articles about vags in the 1924 edition of the San Diego Union, Tribune and Daily Bee, and all of these reports associated poor, unhoused people with crime. The articles reveal the negative attitude of the courts towards the poor, even when those up in court on vagrancy charges were working or looking for work. For example, in August 1924, Albert Van was charged with fare evasion for attempting to board a train in order to take a civil service exam to become a mail carrier. When he explained to the judge that he had no money to pay the train fee, he was order to leave town by sunset, or face a 6 month jail sentence. Similarly, in April 1924, a person named only as Cavanaugh was also order to get out of town by sunset, in response to his panhandling in Horton Plaza in order to raise funds to pay an employment agency to secure him a job. On that same day, a person known only as Brzykwy was order to get a job or depart for other fields. Earlier in the same month, a recently arrived English immigrant was given 6 months in jail for sleeping in a vacant lot at 7th & B Streets, after losing his job and running out of money several weeks earlier, and having had difficulties with police before for sleeping in parks.

Having a job in 1924 in San Diego did not guarantee that essentials like rent could be paid for. Browsing the classified ads of the San Diego Union, I discovered that that average wage for commonly in-demand jobs such as auto mechanic, bell boy in a hotel, freight handler, tram car driver, delivery person, store clerk, stenographer, office worker, telephone operator, warehouse worker and construction labourer paid an average of $40 to $60 per month. However, rent for a furnished room averaged $2.00 per day, or about $60 per month, while an unfurnished apartment averaged $30 per month in addition to security deposits charged upfront. Additionally, job applicants were expected to present a neat and clean appearance and this was a challenge for those persons who had no homes, toilet or bathing facilities, lacked facilities to wash and iron their clothes, and could not afford to pay for barbering, hair dressing, and newer fashion clothing and shoes. Furthermore, employment agencies that charged a feee for placing people into jobs had dubious practices such as withholding further fees from wages, providing work on a daily fee-for service basis, and withholding wages altogether. Overall, the working poor faced a myriad of obstacles to getting and maintaining employment as well as affording the basics of housing, food and expenses such as laundry service, toiletries, and medical care.

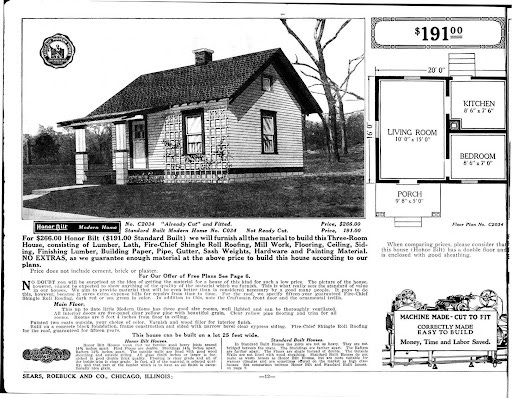

The prospect of buying a home was also an impossible one for the working poor. The classified ads of the San Diego Union featured homes for sale, but even a simple, two or three room house with a kitchen cost an average of $100 per month to mortgage in addition to the need to pay property taxes and common utilities such as water and electricity. Furnishing a home appeared to be extremely cheap compared to 2024 prices, with sofas averaging $50, gas stoves $40, and bed frames and mattresses, about $30. However, if a person was only earning $60 a month, the cost of owning and furnishing a home was out of range. Similarly, renting a home incurred costs that exceeded the average wage.

*******

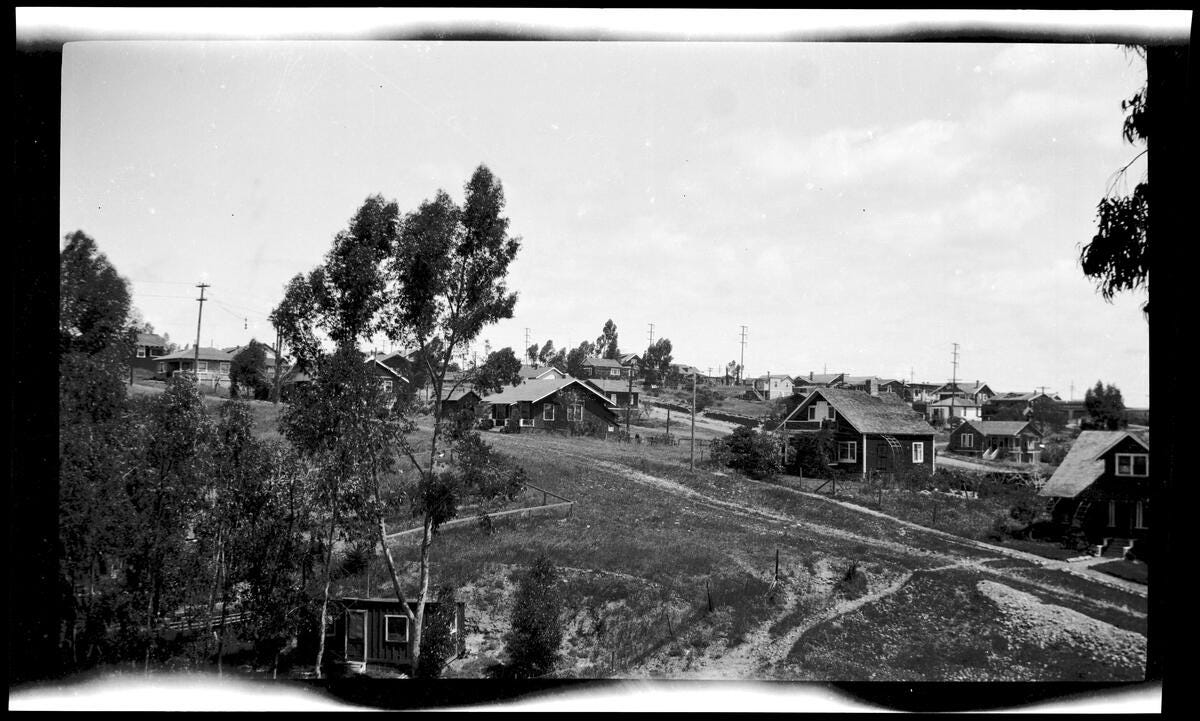

It is ironic that in 1920s the city of San Diego was experiencing a housing boom, but the workers who built these new homes were often unable to afford to buy or rent one of them. In the photo entitled Houses on a Dirt Road in San Diego, the small clapboard houses of 2 or 3 rooms that would evolve into what is nostalgically called small house designs of the 1920s are pictured. San Diego experience the advent of the small house movement beginning in the late 1910s and continuing into the 1940s. This movement was nationwide and intended to improve the quality of life by creating standardised home building practices. Its major contributor was the private architectural development firm Better Homes in America program that claimed a dedication to designing small houses for the working class. Not unlike contemporary real estate development companies, the Better Homes in America program’s focus was on convincing building firms to mass-produce simply-designed, standardised dwellings with economy in construction. However, before the 1934 Federal Housing Act, which guaranteed home loans, the financing of these small homes was entrusted to banks without any regulation. Additionally, the lack of enforcement of scant labor laws and the struggle of unions to gain stable and decently paid employment for working people meant that income was not guaranteed, which made getting a mortgage quite difficult.

Another obstacle to home ownership for the working poor was that, even though companies like Sears Roebuck produced low-cost ready-built kits containing all the materials for building a small home, the cost of buying a vacant lot upon which to place the home was out of range for most workers. In San Diego, advertised prices for city vacant lots that could be bought on credit required a minimum of $20 down and monthly payments of $5 per month for at least 5 years. Should a working person wish to bid on foreclosed lots or homes that had been put up for auction, they not only had to have the cash to complete a winning bid, but also were competing against real estate companies that had the ability to buy parcels and buildings en masse. A further complication was that vacant lots and small homes were sold in what were considered to be the more desirable areas, such as Hillcrest, Mission Hills, Logan Heights, and along El Cajon Boulevard and University Avenue, away from downtown, and this was used as a justification for pricing them higher. This led to a concentration of workers with higher-paid, specialised jobs, such as municipal, military and financial services, and excluded workers in lower-paid industries. Finally, whilst there were no credit reporting agencies or credit scores for workers in the 1920s, there was the need for long-term, stable employment and sufficient cash on hand or savings to be able to pay up-front costs such as down-payments, construction and taxes. Consequently, for those lower-paid workers who were able to maintain some semblance of stable employment and pay for daily expenses and rents, the possibility of setting aside money to save for these costs was virtually impossible, as their basic living expenses depleted their entire daily, weekly, or monthly income.

*******

The millionaire tramp Edwin Brown was convinced that San Diego needed a municipal lodging house similar to the one in New York City and stated in an August 1924 Union Tribune article that he could get the necessary funds and was confident of other persons who would also contribute in order to leave such a memorial behind them. Brown’s perspective was that to build a municipal lodging house in San Diego would alleviate the fearful cost of crime and disease. He supported his argument in favour of such a project by relating his experience in the New York City facility, where he was taken first to a disrobing room, all his clothes were taken to be disinfected while he got an antiseptic bath and a medical inspection, then was given clean night clothes and a clean bed, and then the next morning he got a good breakfast and was free to go out and look for work. By using a combination of public and private funds, Brown asserted that these services could be all as free as the service of a public library.

However, New York City’s Municipal Lodging Houses, which could accommodate and service 750 people, was not favoured by many residents of the city, based on the idea that providing these services for unhoused people was giving them a free ride and encouraging further idleness. It was reported in 1924 in the New York Times that one city official believed that men owe a duty to society not to allow themselves to fall into vagrancy, and that when they do reach that point society must protect itself against them. This protection included the application of the doctrine that necessity knows no law and this included removing unhoused people from the city. Similarly, a writer for the New York Evening World newspaper opined that the Municipal Lodging House’s building cost of $10.7 million and its bath tubs, patent sanitary facilities, dining hall, well-equipped kitchen, white enamelled beds and snowy linen were perhaps too fine for the broken people who drag in their greasy, frowsy rags and tags into the spotless bright work and marble of the municipal lodging-house. When understood without the context of the doctrine of the deserving poor, these comments clearly indicate that the poor do not deserve what were considered the privileges of the municipal lodging house.

Yet, the New York facility was not the alleged luxury free ride that some commentators stated it to be. A 1921 investigative report by a New York Tribune journalist revealed that the facility’s employees treated the residents with about as much consideration as is accorded by a Western cowboy to his cattle in the midst of a round up. The reporter also noted that the food was slumgullion, dormitories were so concentrated that health is endangered and ventilation is nothing short of a nightmare. Amongst the issues with the food was the use of the carcass of a dear hit and killed by a motorist to make a stew for the residents. But, despite this report, the lodging house provided Thanksgiving dinner to 10,000 people and Christmas dinner to 7,500 people in that same year.

*******

Nothing came of Edwin Brown’s 1924 proposal to construct a municipal lodging house in San Diego and from what is revealed in the city’s newspapers, the unhoused continued to be charged with vagrancy and ordered to leave town or face lengthy jail sentences. These included Aidan Fitch, who held a full time job as a porter in a San Diego hotel as well as a part-time job at the Caliente race track in Tijuana, but still could not afford to pay for a place and was charged with vagrancy in February 1924 for sleeping an alley behind his place of employment. In sentencing him, the judge commented that his employment across the Mexican border is not lawful business in this city and if I had my way I would close that line airtight so that not even a flea could get through. Like most who were charged with vagrancy, Aidan Fitch was told to leave San Diego or spend 6 months in jail. A month later, in March 1924, 23-year old Maryle Cosgrove, who was already on a 6-month suspended sentence for vagrancy, and who had been provided employment, was sentenced to a further 6 months for attempting to get her baby from the County Hospital where it is held in the hope of leaving for parts unknown. It is ironic that Ms. Cosgrove was criminalised for attempting to do what judges had been ordering people to do — leave San Diego.

The unhoused persons described in this piece were only a few of the more than 200 people whose names were cited in San Diego newspaper articles about vagrancy court case outcomes in 1924. It is unknown how many of them left the city of San Diego to avoid jail time. But, by December 1924, their presence in the County of San Diego was causing a bit of a panic, due to 14 vags arriving in one day in Alpine, on the 13th, 12 days before Christmas. A group of concerned citizens from Alpine wrote a letter to the editor of the San Diego Union demanding that courts judges in San Diego would request at least a part of these unwelcome visitors to travel in some other direction so that they do not multiply at the present rate and overflow the community. Should this demand not be met, the writers stated that otherwise, before Christmas, we may be compelled to resort to drastic measures.

It is unknown what came of this demand or what was done to the unhoused who had arrived in Alpine. However, 100 years later, in 2024, there are no facilities or services in Alpine for unhoused people, and anyone unhoused arriving there is directed to a shelter in El Cajon, 13 miles away, a city whose mayor complained in 2022 that El Cajon is only only city that county dumps it homeless in and wondered if they are equally distributed in places like Del Mar and La Jolla? While there are no statistics to support this complaint, what is known is that the millionaire tramp Edwin Brown did buy a home in Del Mar in 1924, settled there, and his proposed large-scale lodging house for San Diego’s unhoused was not acted upon, until, perhaps now, with a 1,000-bed facility being planned to provide shelter and services to the unhoused. Thus it is that history repeats itself and San Diego’s unhoused continue to live between rock and a hard place, with little opportunity or prospect to have a home of their own, due to high rents, even higher mortgages, inadequate income, and therefore must comply with whatever plans are put into place to classify, manage and determine their daily lives.

Fanny Elisabeth Wooden Garvey was adopted into a family of “San Diego Black Pioneers” and grew up in an unincorporated part of the city during the 1950s and 1960s. Her first published work was a poem written in kindergarten that was selected for the San Diego Unified School District’s Quest magazine where student writing was featured from the early 1960s to the late 1970s. She has also worked with various creative collectives in the United States, Ireland, and England as well as published works in magazines and anthologies and written scripts for plays and other performative works since the 1970s.