Between a Rock & a Hard Place for 100 Years

Part Two: The “Gig” Economy By Any Other Name Would Smell as Foul

The first man gets the oyster, the second man gets the shell.

(Andrew Carnegie)

by Fanny Elisabeth Wooden Garvey

In March 1924, the California State Assembly passed the California Employment Agency Act, a bill that limited employment agencies to charging a fee of 10% for placing unemployed people into jobs. In response to this legislation, Stanley M. Gue, Deputy Labor Commissioner for the fee-free State Employment Bureau located at 106 B Street in downtown San Diego stated that he “regrets the action of the court as there is a crying need in California for some limitation upon fees that could be charged to men and women seeking employment.” While Gue did point out that the 10% fee cap did abolish the previous 33-13% one that private employment agencies had been charging, he also emphasized that “big labor agencies in the large cities of the state had raised huge sums of money to fight any limitation of employment agency fees.” His final statement on this issue was that workers needed to be aware that there was “no need for them to pay just for a chance to get honest work and there is only one way by which this evil may now be combated and that is through a campaign to have employers place their orders for help with the state free employment bureau.”

The State Employment Bureau in San Diego had opened in December 1923, with Gue as its Deputy Commissioner and Martha Moore as its Assistant Deputy Commissioner. This publicly funded government agency provided a variety of services to workers without any fees charged, including placing unemployed people into jobs, linking them with training, apprenticeship and educational opportunities, compiling labor statistics (including unemployment rates), enforcing minimum wage laws and assisting workers in disputes over the payment of wages. Within 2 days of its opening, more than 1,000 unemployed people had registered as job seekers and an unknown number had also sought wage dispute assistance. Importantly, in an interview in the San Diego Union on December 21, 1923, Gue emphasised that he anticipated “fully 90 percent of the work of the bureau of labor statistics here…will consist of adjusting disputes over the payment of wages.” Furthermore, he pointed out that reports sent out by the State Labor Commissioner show “a like condition elsewhere throughout the state.”

Significantly, on December 22, 1924, Gue informed San Diego media readers that more than 200 cases of wage dispute had been resolved, including the arrest and jailing without bail of Arthur H. Moore, whose Eldorado Development Company had refused to pay wages to workers recruited at the rate of $5 per day for an alleged gold mining operation in Alaska. Significantly, Gue’s success at apprehending Moore was the culmination of a months-long operation initiated by the State Labor Commissioner, based on similar promises made by El Dorado to workers across the state, including in Los Angeles and San Francisco. Researching the classified of the San Diego Union, Tribune and San Diego Bee, over 300 classified ads for El Dorado had been placed by various private employment agencies in the city and this correlated with Gue’s informing the media that more than $1,000 in fees (about $18,500 in 2024) had been collected for the El Dorado employment placements. However, despite the San Diego State Employment Bureau’s achievements in its first year of existence, the San Diego media’s classified columns featured more than 700 ads for private employment agencies throughout 1924, and one anonymous columnist opined that labor conditions in San Diego were good enough to render the bureau’s work futile, because “few complaints have been entered and this is proof that the many employment agencies in this city offer the honest working man a variety of choices for gaining the work he desires.”

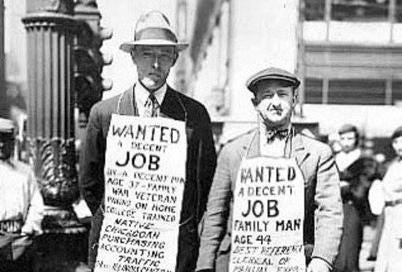

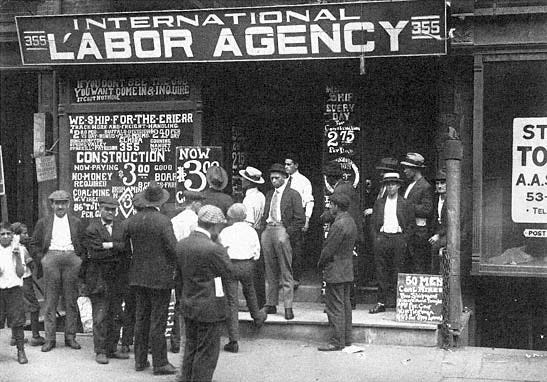

The proliferation of employment agencies in San Diego in 1924, as well as in all the major cities of the United States, virtually controlled access to employment in most occupations. These agencies developed out of the post 1920-1921 economic depression and the high rate of factory and farm foreclosures that resulted from it. By 1924 economic conditions were described as having been impacted by some type of “minor interruption”that was unspecified in a January 16 San Diego Union article. The consequences of all these conditions for working class people were three-fold. Firstly, lack of opportunities resulted in workers moving from place to place, seeking mores table economic conditions. Secondly, employers began utilizing agencies to hire workers in order to cut the costs of maintaining their own personnel and payroll departments. Thirdly, employment agencies made their profits by collecting fees of 33-1/3% from wages paid to the workers they placed. Overall, these conditions led to job insecurity, stagnant wages, and other types of exploitation for workers. One important form of exploitation was the growth of the day labor industry that employed people on a daily basis with no guarantee of a full week’s work or any type of permanent employment. Another was the creation of complex contracts that workers were required to sign in order to be placed in work with clauses that contained deductions for work clothes, equipment, placement and other fees. These deductions placed financial burdens on workers that included being charged so many of them that workers on long-term work placement soften ended up in debt to the agency. Finally, employment agencies operated with little oversight from government agencies, leading to dangerous working conditions that included beatings and other forms of physical abuse as well as a lack of regulation of working hours and break times. Therefore, when Gue and Moore opened the State Employment Bureau in San Diego in 1924, Gue’s description of the practices of employment agency fee-charging as “evil”seems a fair assessment.

Browsing the classified ads in the San Diego Union, Tribune and Daily Bee revealed that most advertised work was controlled by nine employment agencies — Reliable, San Diego Employment Agency, Expert Service Bureau, Star Employment Agency, Model Employment Agency, Western Employment Agency, Employment Specialists, Melruth Employment Agency, and the wrongly named Federal Employment Agency. It is interesting to note that some agencies focused on specific types of workers. For example, the Melruth Agency exclusively placed “coloured help in Coronado,” while the San Diego Employment Agency provided “Filipino cooks to private homes and hotels.” The Federal Employment Agency — named to mimic the United States government’s Federal Employment Bureau — specialised in labourer positions, such as “jackhammer man,” “mucker” and “moulder.” Farm day labor was provided by the Reliable Employment Agency, while the Expert Service Bureau specialised in bookkeepers and stenographers. In addition to named employment agencies, the classifieds also indicate that unnamed individuals were acting as self-proclaimed employment agents, placing ads such as on on April 9, 1924, for “30 pick and shovel men to report at Stockton and Anna Streets, Monday morning, at 7:30 am.” This ad provided no details of the wages for this work or its duration and also did not disclose any fees workers would have to pay.

Wages offered by employment agencies were low compared to union shop pay scales and the type of work most often was considered to be unskilled labor. For example, according to the U.S. Department of Labor’s Bureau of Labor Statistics Handbook for the years 1924 - 1926, wages for unskilled males averaged $22 per week and for unskilled females $16 per week. Daily wages for unskilled males $2.40 per day. Although federal income tax withholding had been mandated by the federal government in 1913, a lack of oversight meant that federal taxes were rarely, if ever, withheld from workers’ wages. Additionally, there were no social programs, such as Medicare or Social Security, nor any state tax withholding requirements. Ideally, this would have meant that workers kept the entirety of wages earned, however, employment agency fees often consumed at least 1/3 of earnings, and, most often, more. This, combined with the lack of stability of employment agency work placements, placed workers in the precarious position of not knowing from day to day if they would be able to earn any money.

The cost of living for the most basic necessities — shelter and food — could just barely be covered by a day labor placement, if a worker could keep all they had earned. For example, the San Diego media classified advertised budget hotel rooms for rent at an average of $1.50 a night and greasy spoon cafes sold meals for between 10 cents and 50 cents. A cup of coffee from a cafe cost 5 cents, as did piece of fruit — most often apples — sold in green grocer shops. Therefore, a worker who earned $2.40 per day could conceivably be fed and housed for a day and one night, and possibly even have 10 cents to spare to visit the cinema, and 25 cents to have their clothes laundered. However, the myriad of new-fangled consumer goods, fashions and leisure pursuits that characterised the 1920s would be out of reach of the average day labourer. Additionally, should the worker’s wages be impacted by employment agency fees, the worker would either become indebted to the agency for wage advances to cover the cost of living, or simply be unhoused, and subject to being jailed for vagrancy. Finally, workers were subject to restrictive employment practices, such as agencies accepting particular demographics and excluding others, and the San Diego media classified ads contained phrases describing work available based on whether a worker was white, coloured or Filipino, as well as clearly stating which demographic was preferred by prospective employers.

The classified ads in the San Diego media in 1924 revealed that workers sought to circumvent the exploitation of fee-based employment agency work placements by offering their services directly to potential employers. However, these advertisements also revealed that workers had to offer lucrative terms for potential employers, such as working for “room and board only,” for no more than a day, or accepting “piecework,” such as sewing or embroidering. Piecework was as it sounds — workers were paid a fixed price for each piece of a good that they produced in their own environments. Importantly, piecework required that workers have stable housing and also that their living conditions were such that the required items would not be stained, soiled or otherwise damaged. Another form of piecework was being paid a set price for harvesting a set amount of produce, such as 5 cents for a bushel of strawberries. However, employment agencies and other types of companies also had an interest in piecework and the San Diego media contained numerous advertisements that promised women $20 or more per week for “sewing and embroidering at home.” Additionally, advertisement from companies located in other cities and states promised women up to $100 a month for “addressing postal cards and envelopes and clipping newspapers.” While no specifics for fees and costs are indicated in these advertisements, the promised income is much higher than wages for unskilled labor and this suggests that these offers may have been a bit too good to be true and perhaps had hidden costs and fees associated with them.

Workers also advertised what appear to be self-owned small businesses, such as requests for “laundry to take home,” and “day labor as domestic servants, construction workers, plumbers, painters, and car mechanics.” The San Diego media displayed ads in which “parents offered their children for farm work, a man and woman offered to run and maintain an apartment building furnace as well as keep the building clean in exchange for lodgings, and a group of young woman described how they could deliver meals in cafes whilst also performing dances for customers.” Likewise, potential employers made offers such as one for “a man to construct a bungalow home and receive a Ford truck in return for the labor.” Finally, workers also offered money to people who could give them work, with one December 1924 advertisement promising “a $20 reward for information leading to steady employment.”

One type of work that persistently was advertised in the San Diego media in 1924 was that of “driver” or “chauffeur.” Both workers and potential employers placed advertisements for this type of work, with some employers being very specific as to whether they wanted a coloured or a white chauffeur, and workers describing themselves in demographic terms. Importantly, the 1920s was an era in which the private automobile was being mass-produced and those who had the means to own a car did not always know how to drive it. Therefore, chauffeurs were both a practical necessity and a status symbol. However, advertisements for chauffeur work also included requirements that drivers did not “drink alcohol, had no bad habits and were reliable.” Additionally, San Diego media in 1924 featured articles about chauffeurs using an employer’s private automobile to operate taxi-type services as well as joyriding, speeding, crashing, and absconding with the vehicles. However, chauffeurs were most often in-home employees of wealthy families and having a driving job could potentially include the benefits of having a place other than live and daily meals, as well as uniforms provided and maintained.

Yet, the employment of chauffeurs was also dominated by the private fee—based employment agencies and this could impact the actual cash wages available to drivers. For example, the cost of licensing, uniforms, hats, room and board could be deducted from a driver’s wages, thereby placing them in the position of not earning home much, or even any, money at all. And, while chauffeurs were required to have licenses to operate vehicles, these could be revoked due to traffic infringements such as speeding, reckless driving, or accidents. Additionally, any fines incurred for these violations had to be paid by the chauffeur, and, incurring them could potentially prevent future employment. Advertisements in the San Diego media classified sections indicated that some drivers advertised their services with the emphasis on the fact that they owned their own car, thereby decreasing costs for potential employers, but also incurring significant costs for drivers.

100 years later, by 2024, the driver-for-hire industry came to be dominated by “app” companies that classified drivers as “independent contractors.” By doing so, this absolved the “app” companies of any responsibility for payroll taxes that provided drivers with unemployment and disability insurance or any payments into Social Security and Medicare. Additionally, this new form of the 1924 drivers-for-hire structure charged fees to drivers that reduced their earnings to only 70% of what they actually accrued. These fees are simply described as external fees on “app” websites and are explained away as “service fees that cover various mandated taxes, commercial insurance coverage and other expenses.” The mandated taxes are described as “local sales tax” and “congestion fees,” as well as “airport fees.” Whilst drivers are charged a fee for commercial insurance coverage, they are also required to maintain coverage of their personal vehicles at their own expense. Finally, the “app” companies state on their websites that these fees are used “to better serve everyone who uses the platform, including customer promotions, marketing and tech improvements”—in other words, the fees are used to pay overhead expenses for the “app” companies.

According to the CalMatters website, “more than 1.4 million workers in California do app-based driving and deliver work for big gig companies, according to the industry’s latest estimates.” These workers are classified as “independent contractors” and the gig economy companies do not pay any payroll taxes for them, which means they have no have no UEI, SDI, federal disability, retirement, Medicare or any other medical insurance. And, not unlike the private employment agencies of 1924, these companies spent huge sums of money — an estimated $200 million — to support a 2020 ballot measure that allowed them to continue to classify workers in this manner. Although the ballot measure was passed, the California State Assembly already had Assembly Bill 5 (AB5) in place since 2019, and this bill aimed to protect workers from being misclassified so that they “would not lose important workplace protections,” including benefits and protections for workplace safety.

Four years after gig economy companies spent millions to support the 2020 ballot measure, a judge for the 9th Circuit Court of Appeals ruled that one of the largest of these companies could not overturn AB5, because “the Legislature perceived transportation and delivery companies as the most significant perpetrators of the problem it sought to address — worker misclassification.” Whilst this protected drivers-for-hire from gig economy company efforts to erode, evade, or eliminate protections afforded to them by AB5, the 2020 ballot measure classifying workers as independent contractors remains valid and can only be overturned by another ballot initiative that would cost millions to create and campaign for. This leaves gig economy workers perched precariously between one bill that protects them and another that potentially erodes those protections.

It has been 100 years since the State of California established local Employment Bureaus to provide job search, employment placement, training and other services to working class persons. Since that time, the State has transitioned to the Employment Development Department, whose website promises similar services, including information on job fairs and workshops, employment protections, and processing of unemployment and disability insurance claims for workers. Additionally, the Labor Board hears cases of wage theft, and the State Assembly and 9th Circuit Court creates and enforces legislation that is meant to protect workers from predatory employment agency practices and misclassification by companies in order to avoid complying with payroll tax and occupational health and safety regulations.

However, the private employment industry is now a part of a global mega-corporation network, with five of the largest United States members having a combined revenue of $212.8 billion. These companies impose mark-up fees of from 45 - 100% of a placed worker’s wages onto companies that hire them, and this keeps worker wages low. These fees remain unregulated by any federal, state or local agencies, despite the 1933 Congressional Wagner-Peyser Act, that prohibited by law charging a fee to either a worker or the employer for job placement. It took just over 30 years for one of the nation’s largest private employment agencies to lobby politicians and achieve in the 1960s the creation and enactment of state laws that made employment agencies “employers” instead of “agents of job placement.” This, combined with the emergence in the early 2000s of the “app” employment companies, has ensured that workers remain employed in the gig economy, hoping that patchwork legislation and court rulings that attempt to address their condition will eventually eliminate 100 years of exploitation, job insecurity and wage inequality.

Fanny Elisabeth Wooden Garvey was adopted into a family of “San Diego Black Pioneers” and grew up in an unincorporated part of the city during the 1950s and 1960s. Her first published work was a poem written in kindergarten that was selected for the San Diego Unified School District’s Quest magazine where student writing was featured from the early 1960s to the late 1970s. She has also worked with various creative collectives in the United States, Ireland, and England as well as published works in magazines and anthologies and written scripts for plays and other performative works since the 1970s.