By Mel Freilicher

Triangle: The Fire that Changed America by David von Drehle on Grove Press, 2003

Common Sense and a Little Fire: Women and Working-Class Politics in the United States, 1900-1965 by Annelise Orleck on The University of North Carolina Press, 1995

Mary Heaton Vorse: The Life of an American Legend by Dee Garrison on Temple University Press, 1989

1. Rose, Clara, & Friends

The Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire of 1911 propelled several of the country’s younger, most vocal and effective women into a lifetime of political activism.

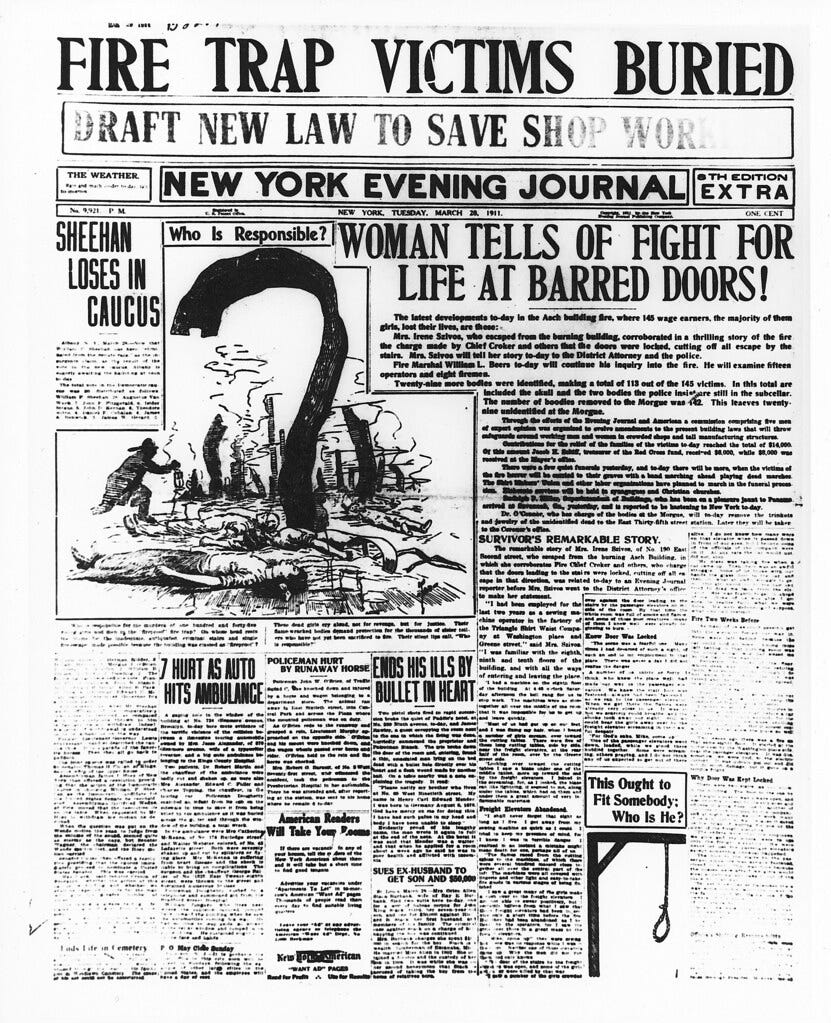

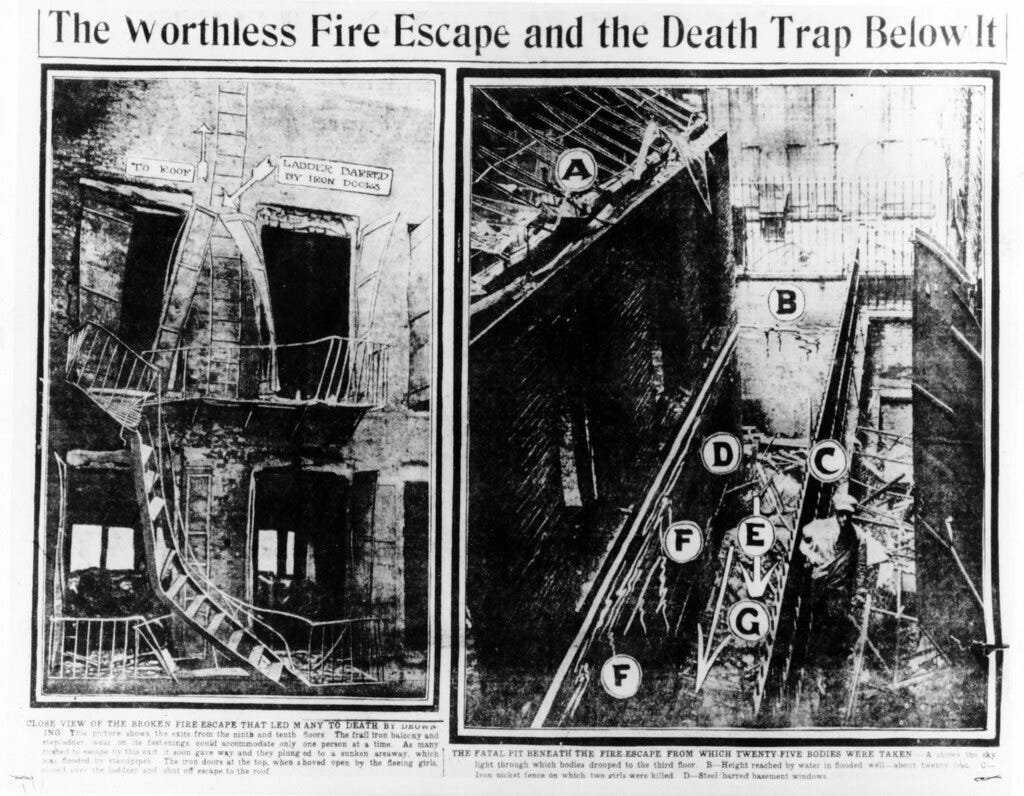

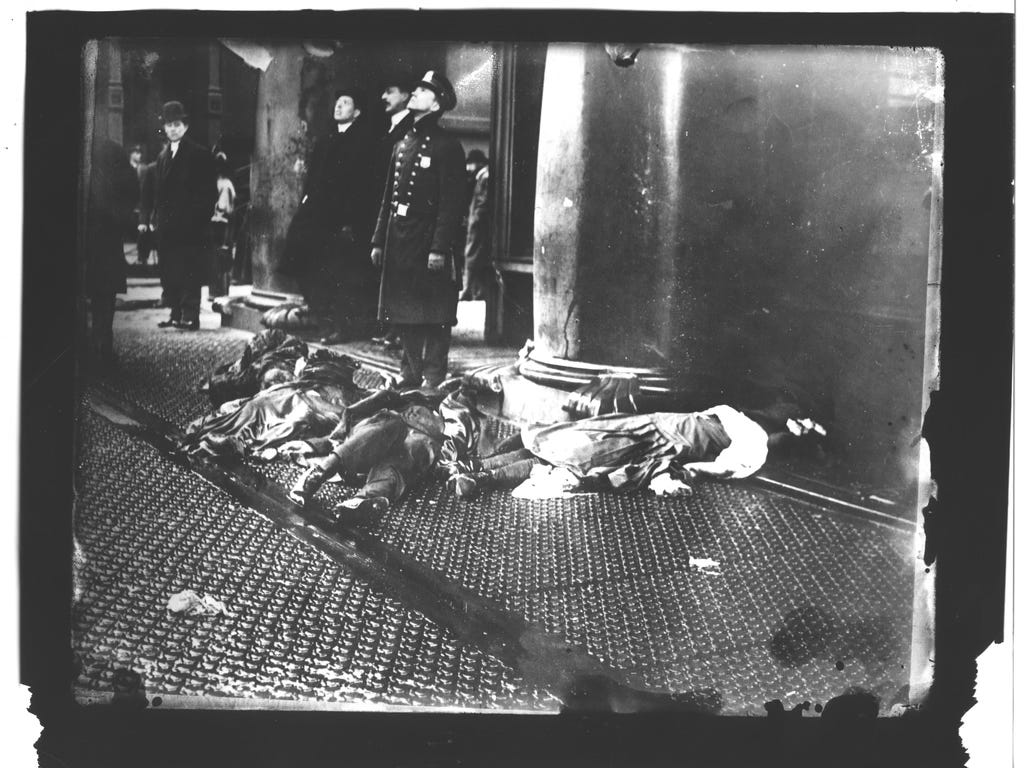

One late Saturday afternoon in March, about 500 garment workers, mostly Jewish and Italian women, were struggling to escape the fire which consumed the factory, located at the Asch building off Washington Square. By the time firemen reached the building, its one fire escape, eighteen and one-half inches wide, had totally collapsed.

Before they could even unroll their lines, Triangle workers were jumping the nine floors from the inferno to the street; some women already on fire looked like human torches. Some dove into nets with such force, policemen holding them turned somersaults onto the women’s bodies.

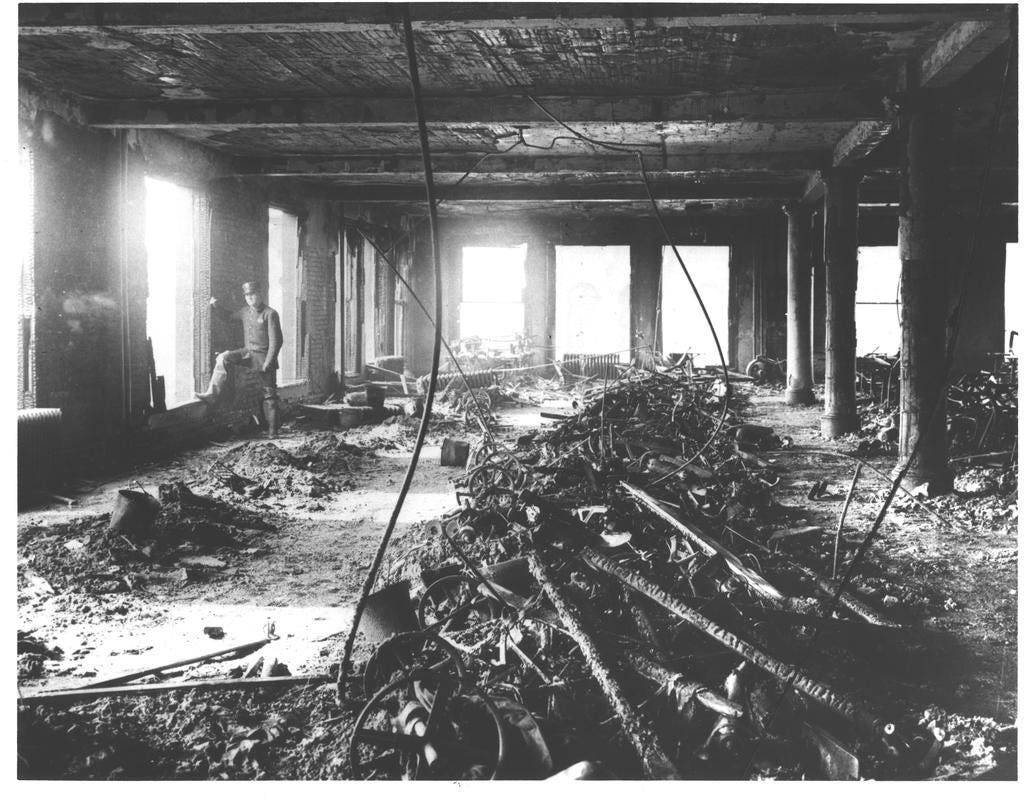

In less than 45 minutes, 146 workers (123 women and 23 men) were dead. A highly documented disaster, due in part to so many eyewitnesses, David von Drehle provides what many view as its definitive account. The fire began in a scrap bin which held two months’ worth of accumulated cuttings, where a cutter (the most skilled and highly paid employees—all male) probably dropped a match. “Cotton is even more flammable than paper, explosively so. Those airy scraps of fabric and tissue paper, loosely heaped and full of oxygen, amounted to a virtual firebomb.”

Von Drehle and Dee Garrison both thoroughly detail the illegal practices of the owners which resulted in the catastrophe. Internal fire hoses emitted no water: there was no water pressure. Building exits were locked. A partition had been put in place so only one employee at a time could pass through. Workers were required to show their handbags to a night watchman as they left—to prevent pilfering of lace or fabric.

Twisted and collapsed by the heat, the single fire escape which the city had permitted Asch to erect instead of a required third staircase quickly became useless. Von Drehle describes the “terrifying” route down the fire escape. Each balcony was only wide enough for one person to walk along it. The sloping ladders connecting the balconies were 18 inches wide. “If, somehow, the workers managed to race down a hundred feet to the bottom of the escape, they would find that it ended futilely over a basement skylight,” with no way to get to the safety of the street.

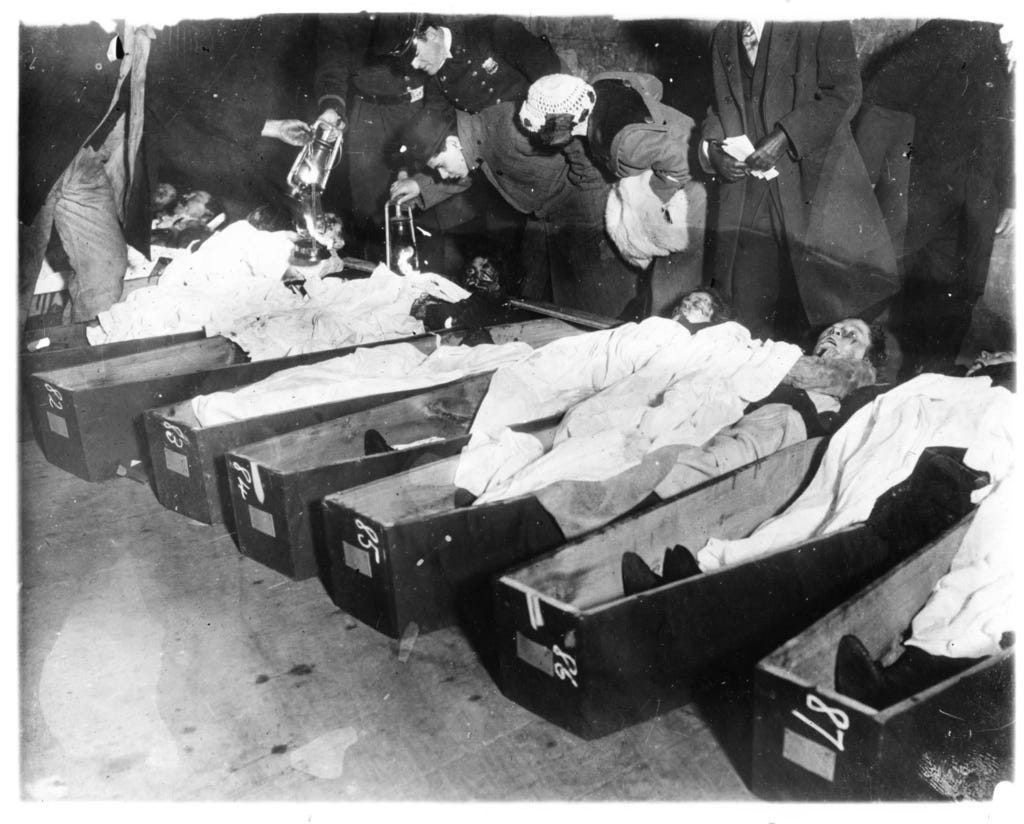

Corpses were laid out in “Misery Lane”—a pier on 26th Street and the East River—for agonizing identification by family and lantsmen. Many bodies were so badly burned, jewelry became the only means of recognition. At the end of his book, von Drehle provides “the first complete list of the Triangle victims ever” by name and age (with 6 unidentified corpses): the youngest being 14, the majority, women in their early 20s.

Acquitted of negligence, the two Jewish owners of the Triangle firm (who were in the building at the time but on a more protected upper floor) soon reopened their shop in a condemned building. “They again proceeded, with official cooperation, to defy the safety ‘laws’ of New York,” Garrison points out. The shop had an extra row of sewing machines that blocked the outside exit.

Max Blanck and Isaac Harris quickly filed insurance claims approaching their maximum coverage. Having habitually paid the highest premium rates in their industry, they were able to collect more than $60,000 above any losses they could prove—about a million dollars in current terms. “This was, in a sense, pure profit,” Von Drehle comments, “more than four hundred dollars per dead worker.”

New Yorkers responded to the fire with an unprecedented outpouring of relief donations, mass meetings, and emotional speeches. But it wasn’t necessarily clear if anything would change. In the past, large disasters had resulted in nothing except grief. Von Drehle cites a “gaudy steamboat called General Slocum which caught fire while taking 1400 passengers, mostly women and children, up the East River to a picnic” in 1904. More than a thousand perished, most drowning after they plunged from the burning ship.

Even as the Triangle fire was burning, construction was underway on the Titanic: its capacity would be more than 2400 passengers, with a crew of over 900; it would carry life-saving equipment for no more than a third of them.

Enter our heroines! Rose Schneiderman, Clara Lemlich, Mary Heaton Vorse. My purpose is to delineate their fascinating, productive lives and to contrast the political trajectories of these three key women in the labor movement.

Rose and Clara, both Jewish immigrants from inside the Russian pale, arrived steeped in Marxist philosophy. Their families had joined the flood of roughly two million Eastern European Jewish immigrants who entered the U.S. between 1881 and the end of WW1. Approximately a third of its Jewish population left home, driven by ever more virulent anti-Semitic legislation and violence levelled at all social strata.

Moving to the lower east side meant horrifically squalid conditions, with as many as 800 people per acre in some blocks: a quarter of the families lived 5 or more to a room. In 1909, of the more than 100,000 tenement buildings in New York City, about a third had no lights in the hallway, making nighttime visits to the toilet treacherous. Nearly 200,000 rooms had no windows at all.

As teenage factory workers, both young women, who’d met at Socialist Party meetings, had already been active in several strikes, and become leading union organizers. Rose, a 4’9” cap maker with flaming red hair and legendary speaking powers (famously proclaiming, in 1911, “The woman worker wants bread, but she wants roses, too”) was an official on the Central Labor Council, and in 1906 was elected Vice President of the impactful Women’s Trade Union League (WTUL), composed largely of middle and upper class women in support of labor and suffrage movements.

Formed at the 1903 AFL convention, the WTUL was not an official union but rather a quasi-educational organization; Jane Addams was one of its prime initiators. Membership was open to anyone, wage earner or not, who promised to render assistance in organizing women into trade unions. But as Mari Jo Buhle states in Women and American Socialism, 1870-1920, joining “working-class unionists with middle class ‘allies’ as they were called, formed an association destined to split.”

Periodically resigning but always returning to the WTUL, Rose Schneiderman served as president of both its national and New York branches in the 1920s and ‘30s. She moved through political office in Albany, then D.C. as a New Deal administrator, and personal friend of the Roosevelts. At that point, she was seen by many on the left as the “Old Guard” of the WTUL, playing a conservative role in the labor movement.

Clara Lemlich, with a handful of other young women, on the advice of editors of the Jewish Daily Forward, formed Local 25 of the International Ladies Garment Workers Union in 1906, to serve the female waist and dress makers. But, Von Drehle asserts, men who ran the ILGWU did little to support them, believing women were willing to work for lower wages, and were destined to leave as soon as they found husbands.

Before the fire, Clara had helped lead three wildcat strikes, including two protesting work speedups (greatly increasing in 1905 with the invention and refinement of the industrial sewing machine), and the firing of better-paid male workers in order to hire lower-paid females.

A mesmerizing street orator, Clara had studied Marxist theory at the Socialist Party’s Rand School and remained a staunch member of the Communist Party from the 1920’s on. Schneiderman and other union leaders continued to work with Clara, but with a greater level of mistrust. Never wavering from class-based organizing, for the next 3 decades Clara helped build neighborhood coalitions of housewives to fight for public housing, better education, and price controls on food and rent. (Her son became an officer, and probably a spy, for the CPUSA.)

Two years before the Triangle fire, some 20-40,000 New Yorkers had actually staged the most massive strike of women workers till then, popularly known as The Uprising of the 20,000: affecting over 500 shops, and virtually shutting down production in the garment industry. At that point, New York City was home to 30,000 manufacturing establishments, with over 600,000 employees—more industrial workers than in the entire state of Massachusetts, Eric Foner points out.

Breathing new life into the labor movement, the Uprising of 20,000 transformed the tiny International Ladies Garment Workers Union into a force of national significance. But it had “mixed success for workers. Some won pay increases, and union recognition, others did not,” Anneliese Orleck states.

Tragically, the Triangle Shirtwaist factory contracts hammered out by the male leadership of the ILGWU, without consulting the women strikers, did not include any safety conditions: it having been determined these were of minor importance.

Rose Schneiderman had pulled Clara Lemlich into becoming a chief organizer of the 1909 Uprising, and she rapidly became its public face. Along with support from the WTUL, strikers received logistical and financial assistance from the United Hebrew Trades, the Arbeter-ring [Workmen’s Circle], the Socialist Party, and its weekly, The Call.

The WTUL had been urging organizers who wanted to call for a general strike in their industry to go slow. However, strikers got an unexpected boost when its wealthy, reformist president, Mary Dreier, was arrested on the picket line. An embarrassed judge quickly dismissed all charges, apologizing for the arrest.

Wide press coverage of police brutality heightened public sentiment, and in this atmosphere, the ILGWU agreed to host a general meeting at Cooper Union: speakers to include Samuel Gompers, Dreier, Schneiderman, Lemlich and others. (The Socialist Party held its own rally, featuring the legendary United Mine Workers organizer, Mother Jones, known as “the most dangerous woman in America.”)

Clara Lemlich later recalled, “’Each one talked about the terrible conditions of the workers in the shops. But no one gave or made a practical or valid solution.’” When she cried out, “’I want to say a few words,’ Clara was enthusiastically led to the platform.”

She simply said: “’I have listened to all the speakers. I would have no patience for further talk, as I am one of those who feels and suffers from the things pictured. I move that we go on a general strike.’ The room was rocked by cheers.” Lemlich’s speech was delivered in Yiddish, Orleck notes, which “dramatically illustrated how overwhelmingly Jewish this movement was.”

Somewhat melodramatically, von Drehle’s book opens with a hired thug stalking Clara through a crowd of picketers at the 1909 strike. During an earlier strike that year she was arrested 17 times and had six ribs broken by police and company guards. “Without complaint, she tended to her bruises and returned to the line.” These young women were still living with their families, Orleck points out, and Clara “hid her escapades and bruises from them.”

The bosses frequently resorted to a variety of violent tactics. Downtown gangsters were used as strikebreakers, while police patrolling the picket lines did nothing. The Greater New York Detective Agency sent letters to leading manufacturers, offering “to furnish trained detectives to guard life and property, and if necessary, furnish help of all kinds, both male and female for the trades.” In other words, their nefarious services extended to providing scab labor.

Employers and police basically treated strikers like “’bad’ women whose aggressive behavior made them akin to prostitutes.” At one point, “In an attempt to sully the strikers’ reputations by association,” management actually hired prostitutes to infiltrate the picket line. When they offered suggestions about more lucrative work the girls might engage in, Orleck adds, “fights broke out and police quickly arrested the picketers.”

Shown little deference by police and company thugs, picketers were attacked with iron bars, sticks, and billy clubs. Pressing charges was futile. One judge dropped an assault charge against the police, telling a worker, “’You are on strike against God and nature.’” Only the League’s decision to invite college students and wealthy women onto the picket lines ended the violence.

Alva Belmont, ex-wife of railroad magnate, William Vanderbilt, and heiress Anne Morgan led a contingent of New York’s wealthiest women in what newspapers dubbed “mink brigades.” Fearful of clubbing someone on the Social Register, police grew more restrained. The socialites’ presence on the picket line generated both money and press for the strikes, and proved politically wise for the suffrage cause as well: Alva Belmont, who frequently bailed strikers out of jail, was a suffrage zealot.

Two years after the fire, affluent women again helped stem violence against strikers. When New York’s mayor scoffed at chief organizer, Rose Schneiderman’s, request for him to deputize 50 trade unionists to arrest strongmen hired by employers to break into union meetings, a group of Barnard college women announced they would walk the picket lines. Rose Pastor Stokes (who later became a founding members of the CPUSA), the former cigar maker married to Socialist millionaire J.G. Phelps Stokes, opened five lunchrooms around the city so strikers could eat free of charge.

Reminiscent of the 1909 strike, suffragists flocked to the picket lines to convince workers of the importance of the vote: sponsoring regular entertainments which infused classical music with a women’s right message. Progressive feminist Fola La Follette, daughter of Senator Robert La Follette, mobilized a group of suffragists to accompany strikers to jail: collecting enough evidence in one night to convince her father to sponsor a congressional resolution calling for investigation into conditions of the garment trades.

“But rubbing elbows with the mink brigade did not blind workers to the class-determined limits of sisterhood,” Orleck declares. The Triangle fire itself had “heightened their distrust of upper-class allies who preached sisterhood while counseling patience and cooperation.” At a memorial held by Anne Morgan in Carnegie Hall to raise money for the families of victims of the fire, Scheniderman issued a classic challenge to sympathetic members of the upper class:

“This is not the first time girls have been burned alive in the city. Every week I must learn of the untimely death of one of my sister workers…There are so many of us for one job it matters little if 146 of us are burned to death…I can’t talk fellowship to you who are gathered here. Too much blood has been spilled. I know from experience it is up to the working people to save themselves.”

Before going further into our heroine’s lives and careers, I need to summarize the career of another eyewitness to the fire, Frances Perkins (who I’ve written about before). When Frances heard fire engines and rushed out of her Greenwich Village apartment, she was a 31-year-old secretary of the National Consumers League. “The fire created in her a sympathy for working women rare among middle-class reformers,” Orleck comments, lasting a lifetime.

After obtaining a degree in physics and chemistry from Mt. Holyoke (where she was president of her class), Perkins had volunteered at Jane Addams’ Hull House, studied economics at the Wharton School, and received a Master’s degree in political science at Columbia.

A state labor official in the 1920s, Perkins was then appointed by FDR as U.S. Secretary of Labor, the first woman to ever hold a Cabinet position. An intimate of the Roosevelts, Perkins introduced them to many women organizers of the WTUL, in particular Rose Schneiderman, while also providing “a sounding board and influential support for WTUL ideas about revamping government relationship with employers and workers.”

Initially, Perkins had been hired by the state Factory Investigating Commission to probe conditions that led to the Triangle fire. With the help of two men, Al Smith and Robert Wagner—leaders of the New York State Assembly and Senate—the famous industrial reformer Florence Kelley, and Meyer London (one of two Socialist Party of America members ever elected to Congress), the Commission managed to push a bill through the state legislature, establishing a maximum 54 work week for women in factories and stores.

To prevent salaries from being cut as a result of the new restrictions, they quickly began lobbying for a minimum wage bill: opposed by owners, naturally, but also by the AFL, whose president, Samuel Gompers, argued such laws infringed on unions’ prerogative to negotiate wages. However, between 1912 and 1923, this Commission helped 13 states and Washington, D.C. establish minimum wages for women workers.

But Orleck comments, “These laws were not intended to encourage a young woman to live independently of her family. They sought to provide just enough so that she could survive in a rather grim fashion without having to turn to prostitution to supplement her income.”

By the end of World War I, 38-year-old Rose Schneiderman, “feeling worn out by years of constant organizing,” began to devote increasing amounts of time pursuing legislative change by forging bonds with sympathetic women of other classes, and with male politicians, especially in the ‘30s when big labor grew closer to the government. “To their amazement, they found it was easier for working class women to articulate and win entitlements from an expanding state than from male colleagues within their own unions.”

Eleanor Roosevelt’s forty-year friendship with Rose Schneiderman began when Eleanor’s ambitious husband, then assistant secretary of the Navy, hosted the first International Congress of Working Women in 1919. Two years later, accepting an invitation to a fundraiser for the WTUL, Eleanor soon became an active member. Later, she presented Rose, as League president, with a $30,000 check to pay off the mortgage on the WTUL building.

Before long, Eleanor began inviting Rose and her partner Maud Swarz (national vice-president of WTUL) to the scrambled egg suppers she liked to cook for friends at her house on 67th Street in Manhattan. “A special closeness developed between ER and Schneiderman that would continue until Eleanor’s death…a remarkable bond between a scion of one of the country’s oldest and most aristocratic families and an immigrant daughter of the Lower East Side.”

Orleck tosses off one sentence: After 1925, Rose and Maud “came regularly to the cottage at Val-Kill that FDR had constructed for Eleanor and her friends, Marion Dickerman and Nancy Cook” who had joined the WTUL when Eleanor did. Nothing more is said about the cottage. Or about this prominent lesbian couple, an English professor and Democratic Party organizer.

Orleck describes her book, COMMON SENSE… as “a collective biography of four Jewish immigrant women radicals” (including Pauline Newman and Fannia Cohn) who “rose from the garment shop floor to positions of influence in the American labor movement.” Rife with discussions of relations among male and female politicians and unionists, intricacies of class vs. union politics, and ideological feuds among liberal Democrats, Socialist and Communist Party members, an odd feature of Orleck’s book is an apparent reluctance, or half willingness, to discuss the doubtless complex gender issues involved here.

Although virtually all these leaders appear to have been lesbian or bisexual, that fact is somewhat obscured, and the homosocial bondings among them drawn rather sketchily.

Outing herself in the Acknowledgment page, this author thanks her same-sex partner of many years. But Orleck takes a strangely ambivalent approach to the Maud Swarz-Schneiderman relationship: “There is very little hard evidence that has survived about their friendship, since almost all of their personal papers have been lost or destroyed. We will never know for certain whether the two became lovers or what the nature of their intimacy was.” (We do hear about another Triangle activist’s unrequited love for Rose.)

Then, Rose’s “lifelong desire for respectability…made her never feel comfortable enough to fully immerse herself in her relationship with Maud.” Though they were involved for nearly a quarter century, the women never lived together; Rose continuing to live with her mother.

However, Orleck immediately adds, “They became partners in work and in their travels, and they were invited places together and gave gifts together.” (They also accompanied Eleanor and her children on camping trips.) When FDR was governor of New York, he appointed Maud state secretary of labor, the first trade unionist to hold that position.

Somewhat more bizarrely, the author never discusses Eleanor Roosevelt’s longtime liaison with journalist Lorena Hickok (though she does mention they traveled together, once with Rose, on a “working vacation” to Puerto Rico). This book was published in 1995. In 1992, Eleanor Roosevelt’s biographer, Blanche Weisen Cook, declared, based on their letters, the relationship with Lorena was, indeed, romantic.

The women activists profiled in COMMON SENSE certainly went against the grain politically, and inevitably, socially (few ever married). Totally speculative on my part: perhaps Orleck felt an emphasis on gender issues might prejudice some readers against unionism, or even against Jewish women. (Pauline Newman, it’s reported, declined to publicize being sexually harassed by an ILGWU officer because she didn’t want to “muddy the waters” for future female activists.)

Reminds me of some early chroniclers of the Harlem Renaissance who omitted or minimized discussion of its prominent gay, lesbian and bisexual participants for fear of backlash--which, of course, many individuals felt compelled to rectify in the post-Stonewall era.

The book does contains photos of Triangle Shirtwaist factory activists, Pauline Newman and Frieda Miller, who openly lived together as a couple, with their daughter. But it takes Wikipedia to inform us Mary Dreier, President of the WTUL before Rose took over for a 32 year run, lived with her female partner for 47 years; they were buried together.

Frances Perkins was married for only 2 years before her husband started showing signs of mental illness, and was institutionalized on and off for most of their marriage. Again, Wikpedia reveals, “Perkins privately had a romantic relationship with Mary Harriman Rumsey,” founder of the Junior League, and sister of Averell Harriman. They lived together in Washington, D.C.

When Frances Perkins became Secretary of Labor, she appointed Rose as the only woman on the National Recovery Administration’s Labor Advisory Board: she was expected to write the health, safety and employment codes for every industry with large numbers of women workers. For the next decade, “though still technically president of the national WTUL, Schneiderman became, essentially, a government administrator.” By January, 1934, the New York Times was calling Rose the “leader of nine million women workers in the United States.”

“The two most important people in shaping Franklin Roosevelt’s understanding of labor issues were Rose Schneiderman and Maud Swarz,” Orleck asserts. Introducing them to her husband, Eleanor was surprised by the quick rapport they developed. And within “the casually anti-Semitic, ruling-class atmosphere of Hyde Park,” even FDR’s mother, Sara, “gradually warmed to Schneiderman over the years,” personally welcoming WTUL members to her home.

Orleck comments how intimacy with the President’s family for a “Polish born Jew whose formal schooling had ended when she was thirteen years old” would have made it difficult to criticize the Roosevelts. “People who have that kind of access to the White House rarely feel inclined toward revolution.” Without further elaboration, she adds, “What they did not see--what few people could see then—was FDR’s gift for making formerly marginal people feel like insiders did not alter his politician’s understanding of the realities of U.S. power relations.”

Describing her years in Washington as “the most exhilarating and inspiring of my life,” Rose began to dress more demurely and in a more feminine style; she wore dresses and pearls and carefully applied red lipstick. Some of her successes included helping to shape a code which outlawed children under 16 from working in cotton mills. But a wide-ranging coalition pushing for a single wage for men and women couldn’t make this happen. Rose also condemned New Deal legislation for its failure to deal equitably with African American women: in her efforts there, “she won fewer battles than she lost.”

Rose led the WTUL into increasingly cautious positions. “Partly out of respect for the Roosevelts, and partly in anger over the internecine battles that had almost destroyed many labor unions in the 1920s, Schneiderman…was wary of associating the League with any insurgent union movements, Communist or otherwise.” Some of the younger women began to brand League leaders as “conservative and stuck in their ways”; some in the labor movement viewed Rose as reactionary, as she remained rigid in decades-old opposition to the Equal Rights Amendment

Particularly egregious was her refusal to support the CIO. When John L. Lewis of the United Mine Workers initially led a convention floor revolt in 1935, and formed the CIO, comprising 8 of the AFL’s largest unions, Rose had been the only delegate on the Central Trades and Labor Council to vote against expelling CIO delegates. But she didn’t resign from the Council when the CIO was expelled. And in 1938, despite vehement objections by several women on New York’s WTUL executive committee, Rose denied the request to send a League delegate to the CIO convention.

Even Mary Dreier, close friend, and former WTUL president, wrote to the leaders, “It seems to me that the League Executive Board members are afraid to act with independent judgment in cases…when the AF of L has not acted.” Several “promising young women organizers” decided to leave the League which eventually became moribund; those who stayed felt obliged to curb ties with the Communist Party and the CIO.

After the war, conservative politicians rode to victory in elections, so there was little hope of passing any new labor-friendly laws. Redbaiting was especially amped up in the 1948 investigation of the State Department, and the conviction of Alger Hiss on perjury charges. Since the leadership of the WTUL was devoutly anti-Communist, Rose was never investigated (though many allies, including her lawyer, were summoned to appear before HUAC and McCarthy’s witch hunts).

On the other hand, once Clara Lemlich Shavelson (she married Joe Shavelson in 1913, who also became a dedicated Party member), had been blacklisted from garment factories, she was in the forefront of organizing housewife consumers: her constituency for the next 38 years. While not giving up on trade unionism, Clara had no illusions of the ILGWU becoming a vehicle for revolutionary change.

News of the Russian Revolution “had certainly electrified Jewish immigrant radicals.” It’s not entirely clear when Clara joined the Communist Party, USA; some describe her as a founding member in 1919. Orleck states the most accurate information seems to suggest 1926, the year she and Kate Gitlow, married to a Party leader, founded the United Council of Working Class Housewives.

Socialists, Communists and trade unionists alike had tended to ignore working class wives and mothers. Although a number of United Council organizers were Party members, the CP was not convinced of the efficacy of organizing around cost-of-living issues. They did create a Women’s Commission in 1929, a “neglected stepchild” from the beginning, Orleck declares. Considered mavericks within the Party, its members received minimal staff support and funding.

During the Depression, from New York City to Seattle, from Richmond, Virginia to Los Angeles, and in hundreds of small villages in between, poor wives and others staged food boycotts and anti-eviction demonstrations, created large-scale barter networks and marched in Washington.

As early as 1939, the Hearst papers charged the consumer movement was little more than a Communist plot; investigation by the Dies Committee of the U.S. Congress was halted only by the bombing of Pearl Harbor.

In a 1948 consumer boycott of meat (price controls had been lifted after the war), some newspapers charged the housewife leaders with being too friendly to Progressive Party presidential candidate Henry Wallace. In 1949, HUAC announced it was looking into the background of women who’d organized the ‘47 consumer march on Washington.

Soon after a trip to the Soviet Union in 1951 where Clara adamantly refused to recognize the existence of any anti-Semitism or slave labor camps, the U.S. revoked her passport, and she was summoned to Washington to testify. In subsequent years, she and her family were frequently visited by the FBI.

When the Shavelson family first moved to the Brownsville section of Brooklyn in 1917, 33-year-old Clara had a three-year-old son and an infant daughter. For at least 15 years before their arrival, Brownsville, a longtime Jewish immigrant ghetto, was “an activist hotbed…where everyday discourse was saturated with the language of Socialism and trade unionism.”

Wartime food and rent increases became fodder for Clara’s vivid street corner orations. In 1917, housewives there joined Jewish women across New York City in a series of food riots followed by boycotts of kosher meat. The nest year, Brownsville women led the way for what would become an intense, months-long battle between tenants and landlords in several Jewish neighborhoods.

A virtual moratorium on building during the war years had left the entire city in the grip of a severe housing shortage. Families unable to pay rent increases had no chance of finding other housing. This rent strike resulted in the formation of a long-term advocacy group, the Brooklyn Tenants’ Union, made up primarily of housewives: a new level of organizing made possible by U.S. War Department agents, who during WW1 had mobilized millions of housewives into Community Councils for National Defense.

On these foundations, as well as on traditional Jewish women’s charitable associations carried over from Eastern Europe, neighborhood organizers began to build tenant and consumer groups. Modeled on the principle of trade unionism, members of the formidable Brooklyn Tenants’ Union held union cards, walked picket lines, and spoke the language of class conflict.

By May of 1919, this organization boasted 4,000 members who pledged not to pay their rents until increases were rolled back. One judge accused strike leaders of seeking to form a “tenant’s soviet.” Even New York’s tough, conservative Tammany mayor, “Red Mike” Hylan, formed a Committee on Rent Profiteering, urging judges to be lenient in eviction hearings, and requesting federal aid to provide cots and tents for the evicted. Methodist and Episcopal churches announced they would open their doors to them.

But the women rent strikers “had no intention of being evicted quietly.” In Brownsville, housewives attacked two landlords, pouring boiling water from teakettles on those who arrived to carry out their evictions. In an incident making the front page of the New York Times, women activists successfully blocked the eviction of 450 families by showing their tenant union cards to movers, and appealing to their sense of solidarity not to break the rent strike. Housing court judge Leopold Prince called for municipal, even federal action. “Bolshevism,” he declared, “appears to be running riot over the city.”

2. Mary, Mary…

In her mid-thirties at the time of the Triangle fire—6 to 8 years older than Rose and Clara—Mary Heaton Vorse’s Village bohemian credentials were already established, as a founding member of the Liberal Club, and an early editor of The Masses. Soon to become involved with the new Heterodoxy group of extraordinary women centered around Greenwich Village, Vorse was then instrumental in founding the Provincetown Playhouse.

Coming from an extremely wealthy family, Mary’s trajectory was quite different from these other activists. Often wintering in Paris, New York or California, she grew up in a 24-room house in Amherst, Massachusetts. Her mother, Ellen Heaton, could trace her English ancestry back to the settlement of the New England colonies in 1630. At age 18, she married a 39-year-old “fabulously wealthy visiting seafarer,” who made his fortune in the China trade and as a liquor merchant serving the 1849 San Francisco gold rush boom.

Idiosyncratic, but extremely conservative all her life, Ellen Heaton opposed women’s suffrage on the grounds that “too many fools are already voting.” The only product of Ellen’s second marriage (she had five older brothers), Mary learned to speak and write French, Italian, and German before she was 15. Always rebellious, she studied painting in Paris and in New York at the Art Students League. Recognizing her own lack of talent, Mary turned to writing popular, light fiction to support her two children--especially crucial after being totally disinherited in her mother’s will.

Months before the fire, Vorse had become a district leader, joining middle class women on the New York Milk Committee. For a year, the Committee distributed free or low-cost pasteurized milk: when the infant mortality rate dropped by some 13%, the city took over the program. Many commentators attributed the high death rate of infants of the poor from a host of illnesses like scarlet fever, diphtheria, and tuberculosis, not to polluted or watered down milk but to neglect of their children by ignorant immigrant mothers. “Shocked out of complacency,” Mary responded by writing angry rebuttals with statistical data.

Eyewitness to the Triangle fire, Mary Heaton Vorse’s “transforming experience,” as her biographer terms it, led to her becoming the country’s foremost labor journalist (most often participating in the strikes she was covering). Her knowledgeable accounts found their way into major journals normally closed to writers associated with the left, like Harper’s, Scribner’s, and the Atlantic. But, Dee Garrison adds, Vorse also “wrote for intellectuals and reformers in The Masses, the Nation, and the New Republic, and for workers in hundreds of dispatches for union newspapers and union press.”

One of two women reporting on the shameful Scottsboro Boys trial, over the course of a long lifetime, Vorse covered nearly every major strike in the steel, coal, textile, and auto industries. After war broke out in Europe, Mary helped found the Women’s Peace Party, for which she served as delegate to the International Congress of Women held at the Hague (which spawned the Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom). Remaining in Europe to report on the war for several American magazines, she focused on its effects on ordinary people, especially women and children.

Redbaited from almost the start of her career, Vorse was never a member of the Communist Party, having witnessed many cruel excesses of the centralized Russian state; in 1921, she was among the first to tour the famine area as a Moscow correspondent for the Hearst papers. Also, she was one of the few American reporters to visit Bela Kun’s short-lived Communist government in Hungary in 1919.

A major supporter of the Wobblies, in the abysmally cold winter of 1914, as her friends appeared with their heads laid open by police clubs or disappeared into jail on trumped up charges, her Village apartment became the staging center for the IWW-led branch of the unemployment movement.

Further catapulting Mary into a lifetime career as labor reporter, she became a close friend of the young firebrand, Helen Gurley Flynn, who, when they first met at the Lawrence, Massachusetts textile strike in 1912, had already been arrested numerous times for leading IWW free speech movements in cities around the country.

Mary was particularly impressed with the active role women played in the Lawrence strike. Not only leading the picket line, running soup kitchens, and organizing relief, they also voted on all strike decisions and were elected to the Strike Committee. Margaret Sanger led a highly publicized march of the strikers’ children to the homes of relatives and supporters in New York

In 1917, IWW leaders, “Big” Bill Haywood, and Elizabeth Gurley Flynn, asked Mary to come to Minnesota to report on, and help publicize, the Mesabi Range mining strike. Agreeing partly out of concern for Flynn, whose lover, the anarchist Carlo Fresca, was in jail there, Mary picked up assignments from the Outlook, Harper’s Magazine, the New York Globe, and the Masses.

Since war conditions restricted immigration, employers found it difficult to import scabs, relying instead on the companies’ private armies which “prevented picketing, harassed strikers, and arrested workers on trumped up charges.” The historian Melvyn Dubofsky also noted, “Often drunk and brutally aggressive, the private guards established a veritable reign of terror” over the 35 identifiable large minorities on the range.

By 1902, most of the mines on the range were owned by the nation’s first billion-dollar company, the U.S. Steel Corporation. The strike was lost: owners granted a few concessions, but an open shop was retained, and the Mesabi miners remained unorganized until the CIO drive of the 1930s.

Allegedly, Vorse met with several anarchist, Communist, IWW, and AFL leaders in Chicago, where, under the leadership of John Reed, they formed a plan to overthrow the U.S. government and kill all high public officials—or so the Thiel Detective Agency, an anti-union group for hire, informed the Justice Department in November, 1919. Prisoners taken in the Red Scare Palmer Raids in Chicago were questioned about the supposed meeting.

Infamously, the Espionage Act resulted in smashing the IWW and generally decimating the left. When her friend Bill Haywood was sentenced to 20 years and fined $20,000 (impelling him to escape to Russia), Vorse wrote: “There is an unwritten law that you break at your peril. It is: Do not attack the profit system…It is because the IWW believed that the workers should control industry that wartime hysteria was used to put leaders in jail.”

Mary’s outrage quickened the Bureau of Investigation’s (later to become the FBI) surveillance. Monitoring her for at least another thirty-six years, she continued to report on child labor, infant mortality, working class housing as well as labor disputes for several newspapers, including the New York Post and New York World. The Lusk Committee, founded by the New York State legislature in 1919, listed her “seditious” associations. Vorse’s name also appeared on the well-publicized blacklist of the Daughters of the American Revolution.

American labor exploded in 1934 in major strikes around the country. Elizabeth Dilling’s private publication, The Red Network, in that year was, according to Dee Garrison, “the single most irresponsible—and most humorous—example of anti-Communist propaganda”: listing 460 organizations and 1,300 persons as American members of the international Communist conspiracy, including Vorse along with most of her close friends and a host of liberals like Eleanor Roosevelt, and Jane Addams.

Although the few journals reviewing the book “treated it as a howler,” by 1938, when the Dies Committee made redbaiting a popular pastime, “Dilling was hailed as an incontestable authority to support congressional attacks on the civil liberties of political dissenters.”

In 1935, the New Deal Commissioner of Indian Affairs, Mary’s old Village friend, John Collier, hired her as publicity director of the Bureau, and editor of its biweekly journal, Indians at Work. Collier vigorously attacked the prevailing idea that Native Americans should be assimilated into white society. For the next twenty-one months, Vorse’s publication propagandized for reform, castigated opponents and featured articles from anthropologists, lawyers and conservationists.

According to FBI records, her personnel file indicated “she had been cited for inefficiency” prior to her resignation in 1937. However, Garrison notes, the full story is much more interesting. Vorse and her colleagues on Collier’s staff were smeared before both Senate and House subcommittees on Indian affairs as “Christ-mocking, Communist-aiding subversives bent upon finding a back-door entrance for the establishment of Communism in the United States and supplanting of the Stars and Stripes with the red flag of Moscow.”

Mary had frequently met with individuals associated with what would come to be called the Ware group, including Hal Ware (son of Communist leader, “Mother Bloor”), his wife, Jessica Smith, and others. Most of them were Communists interested in farm policy, and involved with the left-liberal faction within the Agricultural Adjustment Administration—almost all were fired in 1935.

“Vorse came naturally enough to this group,” her biographer points out, having long been interested in the plight of the southern tenant farmer. Traveling with Jo Herbst in 1932 to report on the farm strike in Iowa, she’d encountered Hal Ware organizing farmers in the Midwest.

“The acceptance of Vorse into the Ware circle, despite her public alignment with anti-Stalinists as a contributing editor of Common Sense, is another indication of the fluid alliance between liberals and radicals in the early thirties,” Garrison suggests, “before the Cold War freighted such associations with ominous implications and personal danger.”

In Washington, Vorse’s participation in this network was fated to receive wide attention in 1948 for its connection to the Alger Hiss affair, the State Dept. official involved in establishing the U.N., and accused of being a Russian spy. This case “rested entirely on Chambers’ testimony that Alger Hiss was a member of the Ware circle,” which he claimed was a cell of the American Communist Party.

Whitaker Chambers, then a senior editor at TIME, and former member of the CPUSA, testified before HUAC that Hiss’ own denial had been perjured testimony (for which Hiss spent several years in prison, protesting his innocence). Chambers was particularly incensed at the role Hiss played in the Yalta conference which divvied up Europe at the end of WW11—giving Russia, Chambers believed, too great an influence.

Garrison’s book covers multiple aspects of Mary Heaton Vorse’s ground-breaking life and career, including friendships with notables like Flynn, Dorothy Day, Lincoln Steffens, Emma Goldman, Crystal and Max Eastman, Roger Baldwin, Frances Perkins (who later “snubbed” Mary—presumably, the first female Cabinet member felt she had to distance herself from her radical connections). One lover, Robert Minor, gave up a major job as cartoonist on a Pulitzer newspaper to work on the Masses. Like Vorse, he began by mistrusting Soviet style Communism, but soon became a diehard, lifelong supporter.

Reporting on, and sometimes serving as publicist for many major strikes, especially in the steel and textile industries--such as Gastonia, North Carolina (where she was driven out of town by night riders); Flint, Michigan; Harlan County; the CIO sit-down strikes in the auto industry—during WW11, Vorse was perhaps the oldest American war correspondent. Afterwards, serving in Italy with the UN Relief and Rehabilitation Administration.

“Vorse’s most unique contribution to the labor journalism of her time is her consistent attention to the role played by women,” Dee Garrison asserts in an introduction to a volume of Mary’s writing, Rebel Pen. For example, in “How Scottsboro Happened,” a 1933 piece for The New Republic, she viewed the perspectives of the two girls who falsely accused the defendants of rape (one recanted the following year)—not to defend them, but to illustrate the “poverty and ignorance” of their backgrounds.

She wrote: “Victoria Price was spawned by the unspeakable conditions of Huntsville. These medium-sized mill towns breed a sordid viciousness which makes gangsters seem as benign as Robin Hood and the East Side a cultural paradise. As you leave Huntsville you pass through a muddle of mean shacks on brick posts standing in garbage-littered yards. They are dreary and without hope. No one has planted a bit of garden anywhere.”

Victoria Price “worked in the mill for long hours at miserable wages, and here was arrested for vagrancy…and served a sentence in the workhouse on a charge of adultery. Here she developed the callousness which made it possible for her to accuse nine innocent boys.”

Vorse’s well-received 1921 book, Men and Steel, features many interviews with women in strike zones, especially those whose husbands had been killed or blacklisted--effectively dramatized by dialog techniques she’d learned writing fiction. Alternate sections describe picket lines, strike meetings, company brutality, living conditions of miners’ families. (All told, Vorse published 18 books, and countless articles.)

Vorse also played an integral part in publicizing yet another government frame-up--of the self-avowed anarchists, Sacco and Vanzetti, convicted of murdering a guard and a paymaster during an armed robbery of a shoe company. Traveling with Elizabeth Gurley Flynn to the Dedham, Massachusetts jail to visit Sacco, and meet with his wife, Vorse’s reports on these interviews, in the New York Call, and in Norman Thomas’ magazine, the World Tomorrow, were among the first published journal alerts to the significance of the case.

After bringing their plight to the attention of the ACLU at their Executive Committee meeting, Felix Frankfurter, later a Supreme Court Justice, eventually took over the Sacco and Vanzetti Defense Fund: assisted by the ACLU, enlisting prominent intellectuals in the cause.

An early resident of the Village, Mary was one of the first of her set to buy a house in Provincetown. “In part, due to her influence Provincetown had already become, by 1913, a kind of summer resort for the New York intelligentsia.” The Provincetown Playhouse, of which she was a founding member, showcased many controversial plays, such as those of Susan Glaspell and, especially, Eugene O’Neill.

The Playhouse’s first performances took place on Mary’s fish wharf. Within a few years, the Provincetown Players decided to do a season in New York, later establishing their own groundbreaking theater in the Village.

Garrison also discusses Mary’s two-year morphine addiction (with a several month relapse a few years later), complicated by increased use of alcohol. Four months pregnant at age 47, she fell down a long flight of stairs, causing an immediate miscarriage. A local female doctor treated her with morphine. Although some medical authorities had warned against it, many doctors continued liberal use of morphine—which was easily available in dozens of patent medicines before 1914.

Married twice, both husbands died young: the first was a journalist, a friend of muckraker Lincoln Steffens, and he encouraged Mary to write. For many years Mary was a single mother raising three children. With many lovers, and being away from home on assignment for long stretches at a time, she felt intense guilt about her children not having a “regular” mother, as her daughter Ellen complained. “Through most of the 1920s, Vorse was obsessed with one thought,” Garrison claims. “She had failed her children.”

Ellen was “either sullen or hysterical, always depressed and accusing while Vorse was placating, ‘cheerful,’ and ‘rational.’” These difficulties didn’t resolve themselves till Mary was in her mid-seventies, living alone in her Provincetown home; her adult children all seemingly well- adjusted, and productive.

Anneliese Orleck’s Common Sense…also emphasizes how unhappy Clara Lemlich Shavelson’s children were with their mother’s frequent absences, and their embarrassment at her neighborhood rabble-rousing. Severe conflicts occurred later when her daughter was engaged to an African American man (despite the CP’s ideological commitment to expose and combat racism). But Clara had a supportive husband, and in the end, her children all became radicals. Still, motherhood was a major challenge in both women’s lives.

When initially deciding how to delineate the lives of these three women activists, it seemed to me the most useful distinction was their relations to the left and specifically the Communist Party, plus the degree of persecution they endured. Not entirely sure why I’m so obsessed with the CP, since I admire many past progressives of all stripes.

Still, historically, the CPUSA seemed to represent the most serious and disciplined attempt to remedy the inherent, utter cruelty of capitalism. McCarthy and HUAC were so ruthless, destroying the lives of many truly salt of the earth individuals. And significantly, not just in the Scottsboro Boys case, but generally, the Party was reacting more strongly to racism than any other group.

In that regard, I certainly don’t dismiss charges of opportunism. “Red Dorothy” Healy’s candid 1993 autobiography (written with Maurice Isserman) details her organizing and participating in many arduous strikes, including with farmworkers, some of which they were winning until the faraway Comintern told Party members to pull out: they’d already gotten the publicity they were after.

A red diaper baby, Dorothy had been in the Young Communist League, and was well known in California for her Pacifica radio show in LA. As a national leader (chairwoman of the Southern California district, and member of the Party’s National Committee), she left the CP late in life, first trying to change the Party from within--even after Khrushchev’s stunning 1956 revelation of Stalin’s murderous purges from the ‘30s onward decimated Party ranks. (How CP members here could have remained blind to Stalin’s tyranny for so long is deeply perplexing to me.)

In the New Left, I always disdained sectarian politics, with their oxymoronic battles: which of the multiple Parties’ multiple sects had the correct line, and the correct Russian/ Chinese/ international Marxist affiliations—and thus would inevitably (scientifically! through the magic of dialectical materialism) lead “the Revolution.” (A shibboleth which felt so deeply absurd in this military bastion of San Diego.)

The Coalitions I was part of were chiefly comprised of independent, non-sectarian leftists with various ideological affinities, and a scattering of Party members, only some self-professed. Most of the Maoists I knew tended to be doctrinaire, fairly self-righteous lesbians, former grad students who’d dropped out to work in factories, and a lovely and earnest Chicano couple.

So many stories from those years, often involving heinous police entrapment. One of the funniest (and quite filmic) anecdotes which I’ve previously described involved watching a room full of dykes change out of their boots and jeans into dresses, stockings, and high heels, rather inexpertly applying makeup and teasing their hair, in order to attend a Maoist cell meeting. This, of course, when all leftist parties, except the Trots, still deemed homosexuality as “bourgeois decadence.”

At some point in the ‘70s, certain Maoist groups, like the Communist Workers Party, decided gay people were oppressed too—therefore they could join the Party! One woman I knew went on a national recruiting tour, under the comic name, Mara Maath.

A friend I met from Harvard (here to get a Ph.D. with Marcuse) told me pathetic tales about when he and his girlfriend—he, a short, intellectual Jew, she a statuesque shiksa, both sharply intelligent, warm, exceptional people—were in a Maoist group in Boston, where sectarian battles on the left were famously brutal.

Assigned to work in the cafeteria of Northeastern University, as union reps, they were told by their Central Committee to call strikes or other work actions which the couple knew full well, and fruitlessly articulated to the powers that be, the rank and file were very far from supporting.

In the Farmworkers Support Group here (we picketed Safeways endlessly, and did fundraising), several CP members (mostly older UCSD professors who had not previously been involved in our anti-war organizing) tried a bizarre tactic at one point to oust the group’s two lone, quiet Trotskyist party members.

There had been a fracas in Coachella Valley where leaders had decreed no party newspapers should be distributed at any of the grape strike sites. Apparently, in one instance when strikers were set to confront scab pickers, some Trots started handing out one of their newspapers. Instead of the intended confrontation, there was an internal scuffle among the strikers.

While this clearly happened and it was a stupid move, it seemed a singular incident; in any case, entirely unrelated to the people in our group. Regarding this incident, to delineate the insidious nature of Trotsky’s followers, at our meeting, these CP members revealed the hitherto unseen “Jesus.”

Standing before us, heavily muscled and tattooed arms folded across expansive chest, obligatory headband, sleek black hair cascading down his back, grimacing, he discoursed mightily on eliminating these two perfidious individuals from the group. I argued rather vociferously, and probably semi-hysterically, against the motion which was handily defeated.

Afterwards, a glowering Jesus came up to me, muttering something like “dirty liberal dog.” “Worse!” I replied, “I’m an anarchist!” Not really accurate, but it elicited the desired apoplectic response. When I repeated this to a young, hirsute undergrad in our group who did identify as an anarchist (having, in fact, changed his name to something close to Kropotkin), he looked aghast, warning me, in hushed tones, against revealing that to any CP member--anywhere, ever.

While Trotskyist party lines were traditionally the most humanistic, quite supportive of feminist and gay and lesbian issues, and the least obsessed with the notion of class as “the primary contradiction” (thus, basically, providing the only viable organizing principle), those groups were not above attempting manipulation.

I remember fervid meetings at the Gay Center (then in a capacious, run-down, charming old Victorian house in a yet-to-be gentrified neighborhood directly east of downtown) to figure out how to fight the Briggs initiative: a villainous state ballot referendum barring gays from teaching in public schools.

One woman who tried to take over the leadership (I’d never seen her before) identified herself as a member of the Trotskyist Socialist Workers Party—you know, all straightforward and above board! But those meetings were packed with new people who nobody had ever seen before, and for that matter, whose gender preferences seemed unknown to anyone. Never stating any outside affiliations, they all voted in unison (“democratically”) with their forthright leader.

Prompting one right wing member of the coalition—a drag queen who ran a downtown, transvestite prostitution ring, was then head of the Teddy Roosevelt Young Republican Club, profoundly involved both with the “Imperial Court,” and with the owners of the city’s bars and bathhouses, and currently a major player in national gay politics—to start spreading rumors about “Nazis and communists” having taken over the group.

In the end, the ballot measure failed—mostly, it seemed, because at the last minute, Our Fearless Governor Reagan came out against it.

The last reputed old-time CP member I had to deal with was a wealthy La Jolla matron with a reputation for trying to control every group she was ever in. For a while, the Republican National Convention to nominate Reagan was going to be held in San Diego: at least 100 individuals—including who knows how many agents--consistently turned out to organize against them (though clearly any actions would have to be held miles from the convention site). Thankfully, the Republicans moved the venue out of town; we wondered if that had anything to do with the surprising strength of the opposition.

I was on the Media Committee with my friend, Marcia (Director of the non-profit--to say the least!—Economic Conversion Council, proposing ways military installations and facilities might be used for peacetime purposes), and C, the one CWP member (or fellow traveler, I never knew which) I really liked—a middle-aged, actual working class lesbian from Chicago. (She did seem rather unrealistic, however: taking a job in a power plant, so she could shut it down, “when the call came.”)

I can’t remember who else was on the Committee, but we worked well together. Everything we put out was censored, edited or just cancelled by Ms. CP who, as far as I recall, didn’t actually have any authority to do so. (She must have been on the ”Executive Committee.”) Frustrated, I’d sometimes call her at home, but the housekeeper, who supposedly spoke no English, always answered. Nobody was ever put through, I found out from others who’d “worked with her” before.

The last strike Mary Heaton Vorse covered, at age 85, was in Henderson, North Carolina where she traveled alone by bus: the Textile Workers Union of America was leading a strike of over 1000 workers, 60% of them women. On the return trip, Mary had a stroke which, to her dismay, partly affected her memory. She wrote nothing in the last decade of her life, and only published two articles in the decade before that.

From the late ‘50s until her death at age 92 in 1966, Vorse survived on funds supplied by friends, as well as on a meager income from renting rooms in her Provincetown house. Walter Reuther invited Mary to the 1962 UAW convention in Atlantic City as an honored guest. Before an audience of 3000, including Eleanor Roosevelt and Upton Sinclair, in a standing ovation, Vorse received the UAW’s first Social Justice Award, with an “honorarium” of $1000--“the grand old lady of labor, again the living symbol of a heroic era,” as Garrison puts it.

Outliving most of her contemporaries, Mary’s passing was only briefly noted in the mass circulation media. But, as Dee Garrison, her elegiac biographer, states, “Vorse’s most significant achievement was her participation in virtually every American social movement which championed greater economic power for workers, racial minorities, and women; world peace; or economic democracy. Again and again, she sensed the movement and moved to the appropriate place where the action would begin…present at major strikes and international hot spots, always in the vanguard of key political movements for change.”

As they say in activists’ obituaries nowadays, may this marvelous woman, “Rest in Power.”

Mel Freilicher retired from some 4 decades of teaching in UCSD's Lit. Dept./ writing program. He was publisher and co-editor of Crawl Out Your Window magazine (1974-89), a journal of the experimental literature and visual arts of the San Diego/Tijuana region. He's been writing for quite some time. He is the author of The Unmaking of Americans: 7 Lives, Encyclopedia of Rebels, and American Cream, all on San Diego City Works Press.