By Mel Freilicher

The Cultural Cold War: The CIA and the World of Arts and Letters by Frances Stonor Saunders on The New Press, 1999

We know BIG BROTHER has been watching us forever, way before our smart appliances started clocking our very beings. But less well-known is the story of how the CIA insidiously tried to shape American culture for decades. Frances Stonor Saunders’ groundbreaking book is a detailed and meticulous account of the CIA’s covert actions in the arena of arts and letters since its inception in 1947 through 1967: utilizing dummy foundations, and chiefly its centerpiece front organization, Congress for Cultural Freedom.

The Congress seemed less concerned with the nature of American culture, and more with the attempt to convince Europeans that Americans were not simple-minded philistines. Specifically, they engineered a multi-faceted strategy to woo the non-Marxist left away from Communist Party influence. The literary phase was chiefly funded by the eager Ford Foundation whose assets totaled over three billion dollars by the late 1950s.

In 1952, under James Laughlin (publisher of the significant New Directions books), the Ford Foundation launched its International Publications program. Their first magazine, Perspective, was targeted at the non-Communist left in France, England, and Germany, and published in their three languages. Subsequent magazines included Encounter, Preueves and Cuadernos, directed at Latin American intellectuals.

In 1956, they began Tempo Presente, meant to challenge both Sartre’s highly prestigious Les Temps Moderne, and a similar Italian publication edited by the award winning, anti-fascist novelist, Alberto Moravia. The Congress also subsidized major cultural journals here, such as Partisan Review, Kenyon Review, Poetry, Hudson Review, Sewanee Review, and Daedalus.

A large Ford Foundation grant established the Institute of Contemporary Arts in Washington, D.C., which benefited many leading artist and writers, including Herbert Read, Stephen Spender, Aaron Copland, Isak Dinesen, Martha Graham and Robert Lowell.

The New York Times alleged in 1977 the CIA had been involved in the publication of at least a thousand books. They’ve never made a publication backlist, but Saunders names numbers of books and authors whose involvement with the CIA became known.

According to one of her sources, the aim of the program was to “Get Books published or distributed abroad without revealing any U.S. influence, by covertly subsidizing foreign publications or booksellers.” If covert contact with the author wasn’t feasible, literary agents or publishers could be subsidized to stimulate “the writing of politically significant books by unknown foreign authors.”

The question, of course, is whether these individuals knew where their funding was coming from. In some cases, the answer is unclear, but for the major visual artists we’re coming to, the answer seems to be probably yes (though whether they cared or not is a much thornier question).

In 1964, the Congress’ credibility began cracking open, when The Nation published an article asking, “Should the CIA be permitted to channel funds to magazines which post as ‘magazines of opinion’…Is it a legitimate function of the CIA to finance…conventions, assemblies and conferences devoted to ‘cultural freedom?’”

The CIA had vast resources. In 1949, Congress authorized the agency to spend funds without having to account for disbursements: from ’49 to ’52, its budget increased from $4.7 million to $82 million. It owned airlines, radio stations, newspapers, insurance companies, and real estate.

Their tightly knit “consortium” of allies consisted mostly of former radicals, disillusioned with Marxism due to Stalin’s barbarism: Sidney Hook, Dwight McDonald, Arthur Schlesinger, Irving Kristol, and Nicolas Nabokov (Vlad’s cousin) among them.

First salvo was a gala Masterpiece festival held in Paris in 1952, opening with a performance of The Rite of Spring (with Stravinsky and the French President in attendance). In all, the Festival featured over a hundred symphonies, operas, concertos, and ballets by over 70 twentieth century composers, many of whom, like Arnold Schoenberg, had been proscribed by Hitler or Stalin (Alban Berg had the honor of being banned by both).

Regarding Hollywood, Saunders mostly writes about Carlton Alsop, who first worked as an agent and producer with Judy Garland (and, according to her biographer, Gerald Clarke, was instrumental in her attempts at sobriety), then at Paramount Studios in the 1950s. His reports, part of a by now well-documented, intensive monitoring of the industry’s left wing, summarized the activity of a covert pressure group which Alsop headed (in collusion with most major studio heads), charted with introducing specific themes into films.

Since the Soviets lost no opportunity to underline America’s abysmal race relations, a 1953 report was concerned with black stereotyping. Alsop had secured the agreement of several casting directors to plant “well dressed negroes as part of the American scene, without appearing too conspicuous or deliberate.” One film set on a plantation would include a “dignified negro butler…who is a freed man and can work where he likes.”

“Some negroes will be planted in the crowd scenes in the Jerry Lewis comedy, Caddy,” Alsop reported. Saunders wryly comments, “At a time when many ‘negroes’ had as much chance of getting into a golf club as they had of getting the vote, this seemed optimistic indeed.”

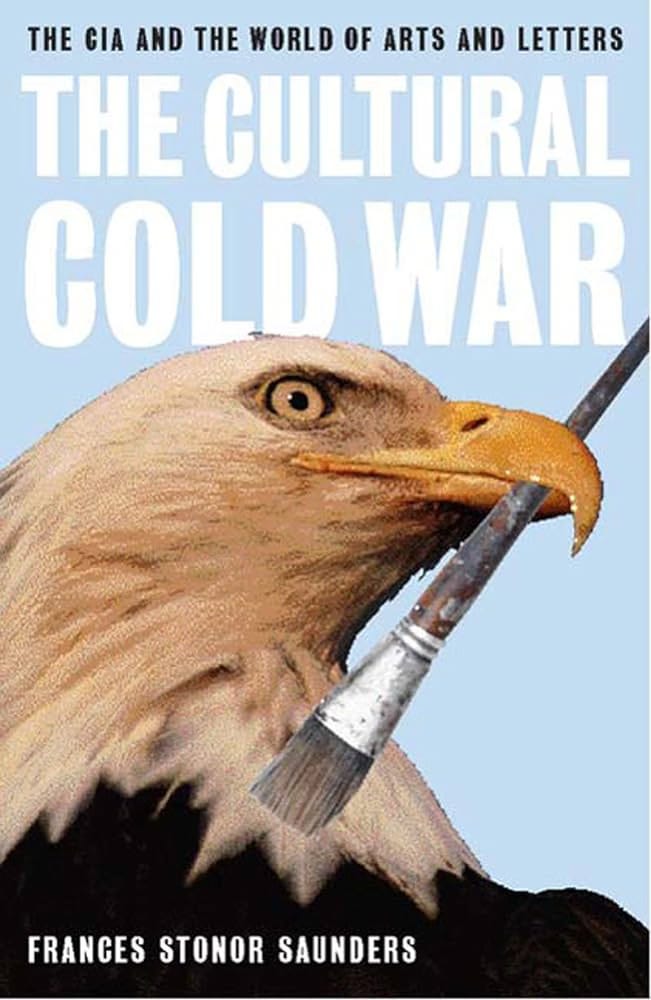

Psychological warfare experts established a secret Cultural Presentation Committee with the chief function of planning and coordinating tours of black American artists on the international stage: Leontyne Price, Dizzy Gillespie, Marian Anderson, the Martha Graham Dance Troupe, and a host of others.

Also including an extended tour through western Europe, Latin America, then the Soviet bloc, of what one covert strategist described as the “Great Negro Folk Opera,” Porgy and Bess. Its cast of seventy African Americans a “living demonstration of the American Negro as part of America’s cultural life.”

“Curiously, the rise of this black American talent was in direct proportion to the demise of those writers who had first given voice to the poor status of blacks in American society.” In 1955, two short stories by Erskine Caldwell were published in a Russian magazine. Cold Warriors in the USIA and the American Committee for Cultural Freedom [sic] condemned Southern writers for depicting “American degeneracy and inanity,” as Sidney Hook put it. Sales of books by Caldwell, Steinbeck, Faulkner and Richard Wright “slumped in this period.”

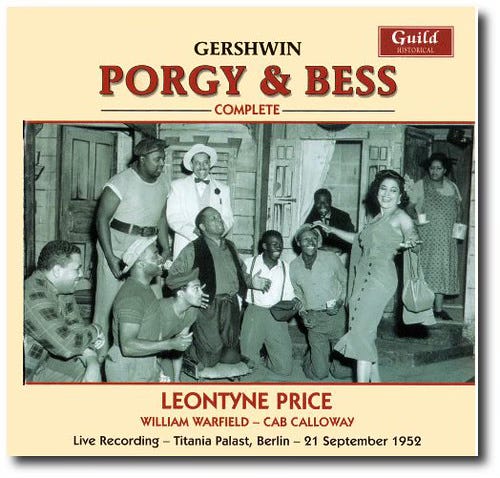

Perhaps the CIA’s most complex, and effective maneuvering was its promotion of abstract expressionist painting, just when Republicans in Congress were declaring “all modern art is Communistic,” even stating “ultramodern artists are unconsciously used as tools of the Kremlin.” Some actually claimed abstract paintings were secret maps of U.S. strategic fortifications(!).

But the cultural mandarin “consortium” took the opposite view. Non-figurative, non-political art was specifically anti--Communist, speaking to the ideologies of freedom and free enterprise—the antithesis of Soviet social realism. The CIA sponsored major, highly touted traveling exhibitions in Latin America, and in virtually every prestigious art institution in Europe.

To promote their agenda, they turned to the private sector, most particularly New York’s Museum of Modern Art, whose president through the 1940s and ‘50s was Nelson Rockefeller (his mother cofounded the institution). With its powerful board of directors including William Paley, owner of CBS, Allen Dulles, and John Hay Whitney (all having complex ties to the CIA), MOMA began collecting and showcasing these works, even selling part of its l9th century collection to do so.

Nelson himself was a keen supporter of Abstract Expressionism which he referred to as “free enterprise” art. His private collection swelled to over 2,500 works; thousands more paintings covered the lobbies and walls of Rockefeller-owned Chase Manhattan Bank buildings.

Rockefeller had myriad direct links to the CIA: he’d headed up the government’s wartime intelligence agency for Latin America. In 1954, Eisenhower appointed him as special adviser on Cold War strategy, and he chaired the Planning Coordination Group which oversaw all National Security Council decisions, including CIA covert operations. Additionally, he exerted influence as a trustee of the Rockefeller Brothers fund, a New York think-tank subcontracted by the government to study foreign affairs.

While Saunders appreciates the artistic merit of this movement and its artists, she provides substantial evidence of its politicization. Commenting, “thus installed within the canon, the freest form of art now lacked freedom,” and suggesting the canvases got “bigger and bigger and emptier and emptier.” In some European showings, museum doors had to be removed in order to get the paintings into the building.

The rumor MOMA was in some official way connected to the government’s secret cultural warfare program was first examined in 1974 by Eva Cockfort, in a seminal article for Artforum, called “Abstract Expressionism: Weapon of the Cold War.” These links, Cockfort wrote, were “consciously forged…by some of the most influential figures controlling museum policies and advocating enlightened cold war tactics to woo European intellectuals.”

The critic Harold Rosenberg wrote that post-war art “entailed the political choice of giving up politics. Yet in its politically shrewd reaction against politics, in its ostensible demonstration that competing ideologies had depleted themselves and dissipated adherents…the new painters and their supporters of course became fully engaged in the issues of the day.”

The natural question arises as to how these artists felt about being used in this manner. Saunders’ speculations are rather dire. At first, we hear most of the Abstract Expressionists had worked for the Federal Arts Project, part of FDR’s New Deal, “producing subsidized art for the government and getting involved in left-wing politics.”

Jackson Pollock, in the 1930s had been part of the Communist workshop of the Mexican muralist David Siquieros. Adolph Gottlieb, William Baziotes and several other painters from this movement “had all been Communist activists.”

After their major successes, on the surface, they all disavowed their left-leaning pasts—except Ad Reinhardt (who Saunders applauds for attending the March on Washington). Of course, many other American leftists were similarly disillusioned.

Robert Motherwell, Baziotes, Calder, and Pollock (“though he was sodden with drink when he joined”) became members of the American Committee for Cultural Freedom. The realist painter Ben Shahn refused to join, referring to it as the ‘ACCFuck.’”(Realist painters during this period were seen as tangential and often shut out of major museum showings.)

Former fellow travelers Mark Rothko and Adolph Gottlieb both became committed anti-Communists, and helped form the Federation of Modern Painters and Sculptors in 1940, “which started by condemning all threats to culture from nationalistic and reactionary political movements.” An active agent for anti-Communism in the art world, when the Federation voted to cease their political activities in 1953, both artists resigned.

Without drawing conclusions, Saunders points out their dismal endings. “Jackson Pollock, a notorious alcoholic, was killed in a car crash in 1956, by which time Arshile Gorky had already hanged himself. Franz Kline was to drink himself to death within 6 years. In 1965, the sculptor David Smith died following a car crash.”

In 1970, Mark Rothko slashed his veins, and bled to death in his studio. Some of his friends speculated he’d killed himself “partly because he could not cope with the contradiction of being showered with material rewards for works which ‘howled their opposition to bourgeois materialism.’”

The International Association for Cultural Freedom voted to dissolve itself in 1979, but covert operations had already been disintegrating for some time, spurred on by intellectuals’ opposition (particularly in the New York Review of Books) and the abortive attempts to control international PEN, which then had 76 centers in 55 countries and was officially recognized by UNESCO as representing the world’s writers.

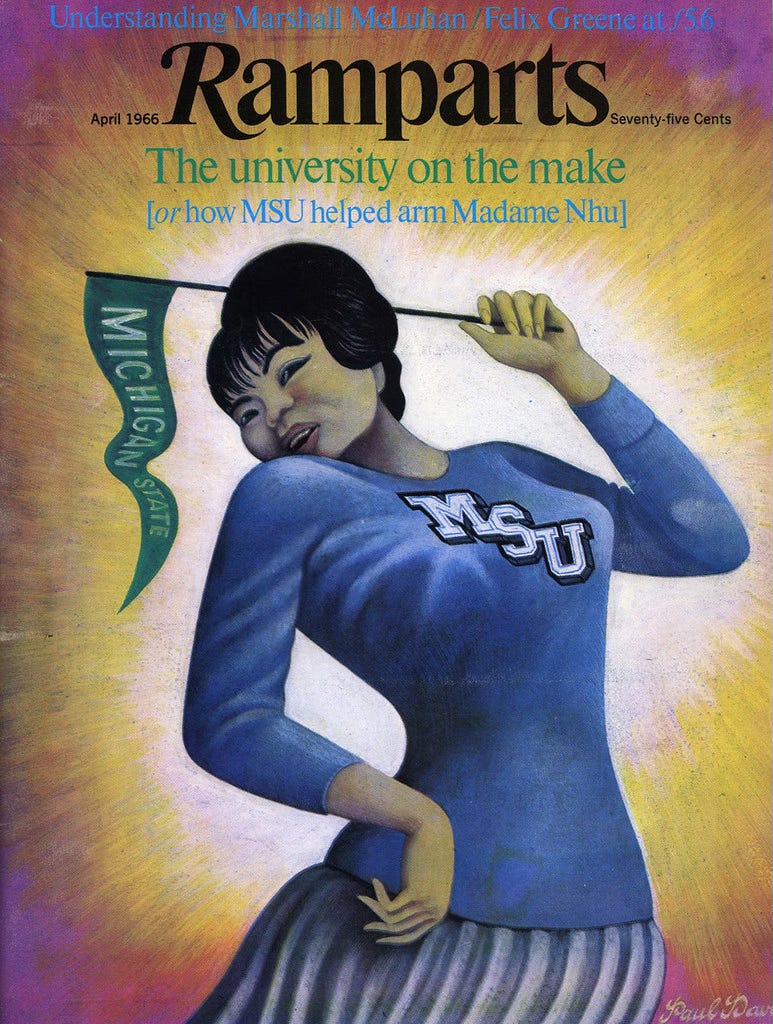

Out of the ‘60s anti-authoritarian counterculture came a slew of alternative media, especially Ramparts, which unlike the others was slickly and professionally produced and graphically sophisticated. Its first piece on the CIA concerned collaboration with Michigan State University during the Vietnam War, to train South Vietnamese police, including in interrogation tactics.

The CIA worked relentlessly to destroy Ramparts, and discredit its editor, Robert Scheer. The magazine, Human Events, ran a smear under the title, “The Inside Story of ‘Rampart’ Magazine.” Its journalists were dismissed as “snoops…eccentrics…ventriloquists and ‘bearded New Leftniks’ with a “’get-out-of-Vietnam fixation.’” Signed by M.M. Morton “the pen name of an expert on internal security affairs,” Saunders writes, “The article bore all the hallmarks of a CIA plant.”

The Deputy General Inspector later confessed, “The people running Ramparts were vulnerable to blackmail. We had awful things in mind, some of which we carried off.” Nevertheless, in 1967, Ramparts published detailed investigations into CIA covert operations, including their sponsorship of the Congress for Cultural freedom and its magazines.

National newspapers picked up these stories, and an “orgy of disclosure” followed. Including the CIA’s involvement with the National Student Association from the early ‘50s to 1967: running its international program and some domestic affairs. Paradoxically, the organization, which advocated for a student-centric vision within American universities, trained a number of leaders who went on to found Students for a Democratic Society (SDS),

A shift occurred in the group when they debated and defeated a proposal to deny support to SNCC, then a fledgling civil rights group. Later, the right-wing Young Americans for Freedom tried to take over the NSA; a number of mostly southern schools completely withdrew as a result of civil rights sit-ins. The organization became defunct in 1978.

One commentator concluded that “before long, every political society, philanthropic trust, college fraternity and baseball team” will be identified as a CIA front.

Much of Saunders’ book concerns profiles of the Cold Warriors (chiefly conservative intellectuals) and many internecine squabbles and counter-accusations, particularly in the midst of their disarray.

For me, the single weirdest fact which emerges: the CIA commissioned a translation of T.S. Eliot’s Four Quartets, then had copies air dropped into Russia! True, this poet was a devout Catholic, thus conservative, but his writing was esoteric, not easily accessible (to say the least). Evidently, no maneuver was too bizarre to preserve our “cultural freedom.”

Mel Freilicher retired from some 4 decades of teaching in UCSD's Lit. Dept./ writing program. He was publisher and co-editor of Crawl Out Your Window magazine (1974-89), a journal of the experimental literature and visual arts of the San Diego/Tijuana region. He's been writing for quite some time. He is the author of The Unmaking of Americans: 7 Lives, Encyclopedia of Rebels, and American Cream, all on San Diego City Works Press.