Enter the Bardo

A Poetic Autobiography of Trauma, Redemption, and Persistence

I’ll be reading from Into the Bardo and Paradise and Other Lost Places on Thursday, November 14th at 11:10-12:35 in the Black Box Theater at San Diego City College and on November 21st at 7:00 PM at The Book Catapult (3010-B Juniper Street, San Diego, CA 92104-5437; (619) 795-3780)

It’s been about a year since my last trip to the emergency room when I awoke in the dead of night spitting blood and wound up in the hospital for a week. I have since recovered from this last of my perilous moments, but that six-month period of my life has left its mark on me as I continue the rest of my journey with a renewed sense of both the deep uncertainty and the profound meaning of every moment we have on this earth.

It took what was already a strong tendency of mine toward a tragic sense of life paired with my own, idiosyncratic version of secular Zen and mixed it with intensified feelings of post-traumatic dread and unexpected wonder.

The perilous sociopolitical context we currently occupy has only served to underline my continuing sense that anything, good or ill, can happen at any time. History tells me that this has always been so, but we all experience things distinctly and see the world that we make and have thrust upon us through different lenses.

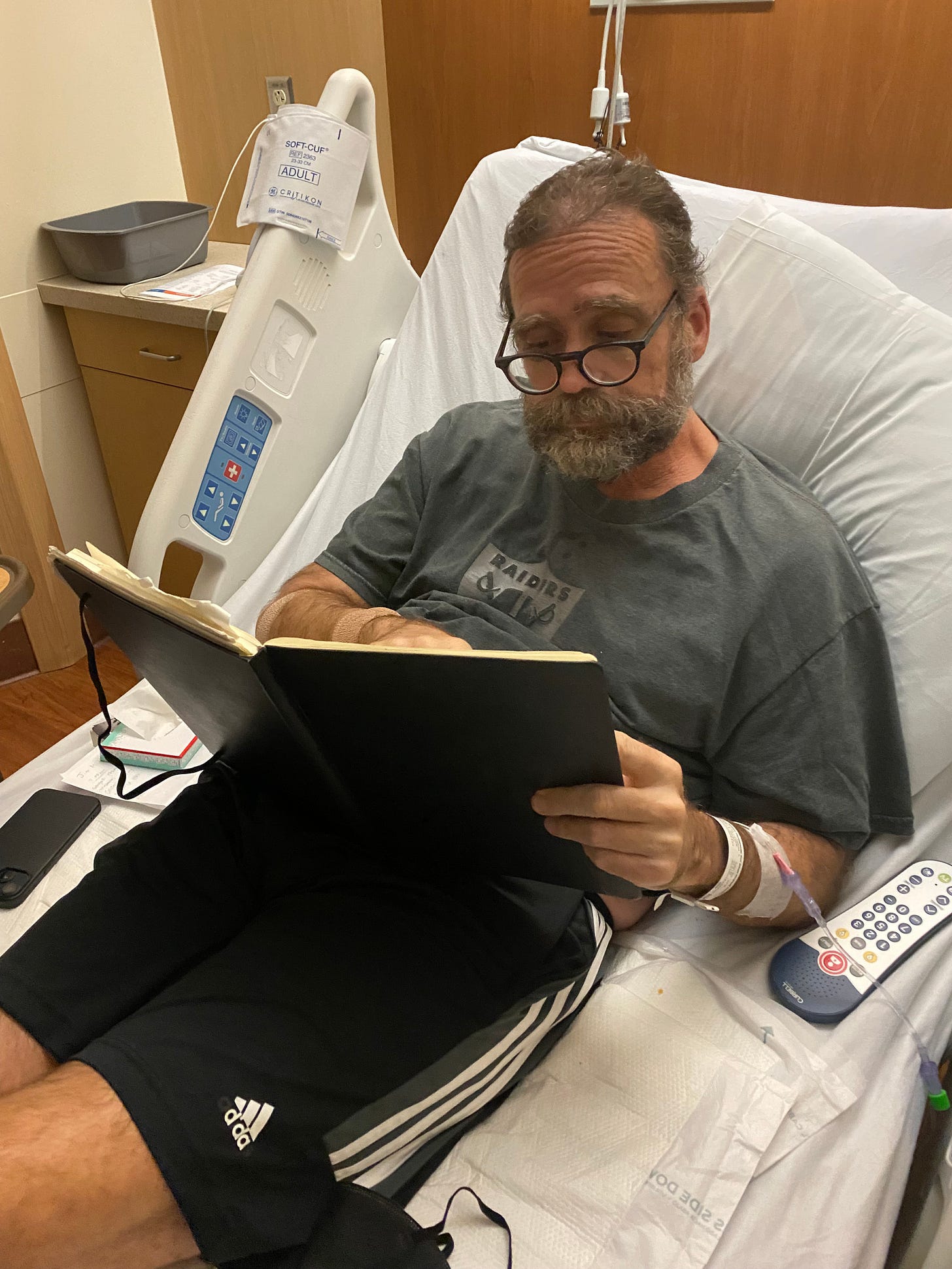

My most recent book, Into the Bardo, was an effort to document and come to terms with my imperiled existence and brushes with death as they happened. The poems it contains were written in Maui immediately after my diagnosis, in various hospital beds, and in my house during my recovery period. In that way, it is a kind of journal of my season in hell and emergence from it.

From the Preface:

In the summer of 2023, I was diagnosed with acute, sudden liver failure, had transplant surgery, a neurotoxic reaction to one of my anti-rejection medications, and multiple near-death experiences.

Tibetan Buddhist nun, Pema Chödrön, in her book How We Live Is How We Die, defines the states of being I inhabited as a kind of “bardo” or transition, which comes from the Bardo Tödrol or The Tibetan Book of the Dead.

As Chödrön observes, the term bardo, “commonly refers to the passage following our death and preceding our next life.” She goes on to say:

. . . a broader translation of the word is simply “transition” or “gap.” The journey that takes place after our death is one such transition, but when we examine our experience closely, we will find that we are always in transition. During every moment of our lives, something is ending and something else is beginning. This is not an esoteric concept. When we pay attention, it becomes our unmistakable experience.

Bardos, then, are states of “continual change,” a “continual flow of transitions” from one thing to another.

I was dying. And then I wasn’t. Now I am aware that, even with new medications to control the worst of my symptoms and make sure my body doesn’t reject my new liver, for the rest of my life, every moment is tentative and precious. The future is always uncertain, becoming and ending and becoming again.

As Chödrön shows us, although “we are not in control” and are forced by circumstance to recognize that “stable, solid reality is an illusion,” what the bardo teachings illustrate, according to her, is that deeply engaging with “impermanence” and “all pervasive suffering” does not inevitably lead to despair but puts us face to face with the “wonderous flow of life and death.” Seeing this flow at the center of a universe where “everything falls apart” enables us to admire the joy and beauty at the heart of the dance of life and death. We can stop our constant running away from and resisting reality and adopt “a new way of seeing our [lives] as dynamic and vibrant, an amazing adventure.”

I lived and am living this.

The first several poems that comprise this collection were written before my formal diagnosis when I began to feel that I was very sick and was dealing with a profound sense of doom. They document that moment when one construct I had of myself was annihilated as everything was torn asunder, and I was forced into the uncertainty of the bardo as I had to accept a disconcerting reality and see what remained of my existence anew.

Also included here are poems from June 25, 2023 until my liver transplant a month later. My transplant operation barely came in time to save my life, and thus resulted in my first near-death experience. I wrote about that soon after my surgery in a column I published in the San Diego Union-Tribune, where I observed that:

The great James Baldwin’s title character in “Sonny’s Blues” says that sometimes you need to “smell your own stink.” I did. I was incredibly humbled, made aware of the lack of control I had over things we delude ourselves we can control. I watched my body and my mind’s decline — I had lost my ability to read deeply, to write and even to think clearly by the time I reached the operation table. My idea of “me” withered, and I was not at all confident I would be there after the surgery. I had to tell the ones I love the most, my son, my wife, my family, my closest friends, that I might not make it out of the operation room, the kinds of conversations I would wish on no one, friend or foe.

Thus, a number of the poems in this book deal with the surgery and its immediate aftermath, while the remaining works address the horrific side effects to one of the medications I was prescribed that led to neurotoxicity and a host of jarring physical and psychological consequences. Hence came another series of dark nights of the soul, which I gradually made my way through only to be hit with an undiagnosed lung infection two months later that left me coughing up blood and put me in the hospital for yet another week as I endured new tests and invasive procedures before my turn for the better.

It was only the love of my family, friends, and community that helped me down this path. In addition to that, my adherence to my own idiosyncratic version of Buddhist discipline and an existential effort to maintain some form of grace under pressure were essential tools for my recovery and redemption. The tale of this journey is ongoing but my experience to date has taught me that it is in these interstices, these bardos of our lives, whether they be painful, joyous, or uncertain and bittersweet, that we are most fully alive.

Sometimes it is only by being shattered that we are truly set free.

What follows are four poems from the beginning, middle, and (for the time being) end of that trip through various manifestations of myself, transient as they were.

The Imperfect Now

Trembling in paradise,

I sit on a chair in the shade

looking out the window

at the expanse of green green grass,

rolling toward the silver road of the sun

glittering on the deep blue ocean.

There is nothing left anymore.

No dreams of a brighter future,

no roads yet to be taken.

Just this imperfect now,

the cool breeze on my face,

a catamaran in the distance,

with its white sails pushing on

against the rising waves.

The palm trees are bowing to the wind,

and the sound of ceaseless surf

is operatic.

My body aches in a thousand places,

and the nausea is raging within

but my eyes still take delight

in tender glimpses of the radiant world—

a turtle’s head pops up and gasps for air,

and the silhouette of the frozen lava flow

is framed by the boundless sea.

I should drown myself in this

pain and longing,

and be reborn diffuse,

surging and flowing,

from matter to emptiness,

part of the nothing

that is inside

the billowing clouds

that aimlessly roam the sky

and make the poetry of the day’s last light

sing

before it dies gently

in the darkness

like the first words of a prayer.

Into the Bardo After Pema Chödrön During the dawning hours, I struggled to sleep, failing to catch even a stray minute of peace. Throughout it all my nurse, Jeff, said to me, in his calm, steady voice, “Go with the river, you can’t fight the river, go with the river.” He repeated it, over and over, like a mantra, and his words stayed with me throughout the night, into the early morning and onward to this day. Before they came to take me to surgery, I said to my son, “If I don’t make it, remember to look at your hand and I’ll be there, always.” My wife wiped away my tears, kissed me, and, as they wheeled me down the hallway, I recalled what I told my son the day before, as I cradled his head in my hands, “Be not afraid, have courage, and be steadfast.” But in my gut, I was sure I would die. Death was smiling at me in the darkness, waiting patiently by my side, whispering to me that it was time to pass over, quietly and quickly, to his lonely kingdom. “It will be a delicate and difficult procedure,” I heard a surgeon say in the operating room, thinking that I had already gone under. So, I lay there, on the razor’s edge. Now, I knew I had no time, no time, no time to waste— Not. One. Moment. More. My body had been screaming this for months, and now the doctors knew it too as they spoke in a semi-whisper, “Let’s start the procedure.” As the anesthesia took hold, I occupied a space between life and death, tiptoeing along the border, trying to impose a semblance of order on my inner chaos. I held tightly to the discipline of just breathing in and out, in and out, deeply and slowly, and letting whatever came to be sit there as it was. Suddenly, I reached a strange state of grace and went blank. My last thought, before the six-hour caesura, was of teaching Hemingway’s “A Clean Well-Lighted Place” in a classroom with a view of a distant tree shedding a few reluctant autumn leaves in the soft breeze. And then deep nothingness, suspended from time. Still lying on my back, I came back to consciousness, furtively, eyes closed, silently repeating to myself a line from Pema Chödrön, “How we live is how we die,” which I seamlessly replaced with a memory of my nurse slowly guiding me forward, “Don’t fight the river, go with it. You can’t fight the river, let it flow through you.” Amen.

Crown of Thorns

I spent days in a prison-like bed,

hemmed in by high, padded siderails

and an alarm set to go off if I left

without a nurse.

Both of my arms were hooked up

to IVs or monitors.

My head was tethered to the

wall behind it

by a cord connected to dozens of

electrodes attached to my

freshly shaven skull,

providing a continuous stream

of images of

brain activity

to a computer monitor

by my enclosure.

At one point, I made the mistake

of looking at myself on the monitor,

and as Melville said of Ahab,

“There was a crucifixion in his face.”

Indeed, after months of taking

what the same old courage teacher called

the “universal thump”

I was humbled, leveled, and

laid as low as I’d ever been.

I too had seen the dark patches

where those lonely, wandering, lost souls

on our streets live every day,

finding no place of solace or refuge,

lurching between terror and rage.

This was my crown of thorns—

not knowing if I’d ever occupy my right mind again,

whether I would ever read, write, or concentrate

with focus.

Would I be set adrift forever?

After days of this, I left the hospital.

Sitting numb and defeated in

the passenger seat,

I was only reached by

the visage of yet another abandoned soul

sitting in a wheelchair

on the street outside the ER,

still wearing a frayed hospital gown,

and holding a sign

that simply said,

“Help.”

This One Small Life

If one day

the blood I spit in the sink

turns out to mean that

I’m dying,

what will this

one small life,

this stream of continuous

moments

that are me

amount to?

As much as we try

to trap ourselves

into a snapshot

in time,

we cannot be measured

or defined by

grief, joy, anger, boredom,

or any of the

myriad moods

that flow through us.

I am not my dying

or becoming,

not agony, ecstasy,

dignity, despair, desire,

pride, envy or humility.

Nor am I triumphant, transcendent,

or absurd—

just all these things

running together

in the flux.

I am made of memories

of running through

the orange groves,

open fields,

rocky hillsides,

green forests,

and sandy beaches

of my childhood.

I am the ballfields,

basketball courts,

grid irons,

grass, dirt, sweat,

and bloody fights

of early contests—

the sound of the baseball

in the glove

and off the bat,

the feel of hitting

and being hit,

the easy grace

and quick movement

of my youthful body,

the sound of sneakers squeaking

on the court,

the basketball leaving my hands

as I leap through

the air.

I am the endless

shelves of books

I’ve read,

the ocean of words,

phrases, sentences,

and passages pored

over, again and again—

Whitman, Lispector, Neruda,

Kerouac, Thich Nhat Hanh,

Knausgaard, Miller, Kafka,

Duras, Baldwin, Oliver,

and on and on.

All the flashes of insight,

meditative moments,

thoughts that cut

deep and hard,

the beauty that cracked

the shell of myself

and left me exposed

to the black of night

and the glory of

the new day,

the unspeakable brilliance

of stars

and the burning heat

of the sun.

The music too is me—

the sounds that crept

into the forgotten corners

of my being

and grew deep roots there

like the silence between

trumpet notes of Miles Davis,

the lilting rise

of Jerry Garcia’s guitar,

slow blues,

tender plaintive voices,

the rush of jubilant, ecstatic noise,

jams, dub, punk, and spare acoustic strumming,

the geometric precision of Bach,

and the forgotten

wonders of melody.

And the art is me—

seeing things just like Robert Frank

on a lonely American highway,

Van Gogh in the garden,

Vermeer peering into the pantry

through a side window.

The funky old houses are me—

Craftsman, Victorian, Spanish style

along with the Modernist landmarks

and the spare lines

that frame the studio

down the street.

I’ve walked by them all

and every wandering step is made

of longing, curiosity,

and the melancholy light

of a late fall afternoon

in the park.

The millions of footsteps

exploring the insides of buildings,

classrooms, union halls, picket lines,

hotels, and ballparks in cities,

and the open spaces outside them,

under the cover of redwoods by the sea,

across the desert, up alpine trails,

or by farms and patches of wildflowers.

I’ve seen there the faces of animals,

the gladness and glory

of their movements—

the sweet eyes of deer,

the lumbering carriage of bears,

and the delicate poetry of birdsong.

I love them all and their brethren

are part of me.

I see myself in

the woodland critters and sea creatures—

the grand elk, big horn sheep,

jack rabbits, chipmunks,

turtles, dolphins,

grey whales, starfish, urchins

and snails

along with a host of animals

lost to the world.

I mourn the vanished,

love and remember them

with bittersweet fondness.

What will the world be

without you?

I too am the faces I’ve kissed,

the breasts suckled,

thighs stroked,

and bodies that have engulfed me.

Is there a more holy place

than where we touch each other

naked and alone together

as our skin tingles,

and flesh engorges and merges

with the other?

I am those intimate caresses

as well as bear hugs,

pats on the back,

hands on shoulders, and

the wonderfully

terrifying moments

when our eyes

lock into each other

and share everything

and more

without words.

I am you, sisters and brothers,

And you are me—

groping from minute to minute,

second by second—

newborn, child, adolescent,

young adult, middle-aged,

old and dying.

I am mother, father, child,

parent, grandparent,

and all those who came before

and will come after

are me,

right now—

staring at the blood in the sink

and knowing it is

our time

but not wanting it to be—

yearning for just one more

perfect fall morning

when there is dawn in me,

one more gentle twilight sky

as I sit on the porch

and lose myself

in the deep glowing red

between the branches

of the grand old pine tree

as cars roll by honking,

ambulances screaming,

and the wings of birds

fluttering above me

like a miracle

as profound as any other

day we have

for as long as we

are still breathing

and deeply adoring the air

that bathes this precious, beautiful,

horrifying, grace-filled world we share.

My blood, your blood,

everyone’s blood

flows together

and apart

in unison,

feeding the life

we witness

and hold tenderly

for how long

we don’t know.

I just know that

this very instant

has always been

and will always be

so full and

glowing with love

that it blinds us

to see it.

You can buy Into the Bardo here or at The Book Catapult in South Park.