By Mel Freilicher

JUST ANOTHER SOUTHERN TOWN: Mary Church Terrell and the Struggle for Racial Justice in the Nation’s Capital by Joan Quigley on Oxford University Press, 2016

I chose Ms. Quigley’s book somewhat randomly for this last section—having seen Mary Church Terrell’s name in a number of readings, not really knowing anything about her. A rather fascinating story, as it turns out. Born in 1863, Mary was the daughter of a reputed millionaire, the South’s wealthiest African American. Her father, Robert R. Church, was the son of a white steamboat captain and his slave—purportedly the descendant of a Malaysian princess.

When his mother died, Robert also toiled as a slave: a dishwasher and steward on his father’s vessels, plying the Mississippi River. As an adult, he opened a Memphis saloon and billiard hall, and brothels that employed white women. Amassing his fortune from real estate speculation and various enterprises, Robert surrounded his family with the trappings of luxury.

Mary’s mother, Louisa Ayers Church opened her own beauty salon, catering to the well-to-do in Memphis. She had learned to read and write from her master, who apparently was also her father; tutoring her in French, he allowed his white daughter to purchase Louisa’s trousseau in New York. Mary’s parents divorced when she was about four.

Mary “guarded details about her childhood,” according to the author, but she did state her father had a “violent temper,” and her mother tried to commit suicide when she was pregnant with Mary. When Mary Church Terrell wrote her long delayed and much belabored, memoir, she apparently left out any personal information. In his rather ambivalent Introduction, H.G. Wells wrote, the volume suffered from a “discreet faltering from explicitness.”

Unfortunately, we don’t learn much about Mary’s internal life. Simply unavailable material, probably. How did she feel about her father’s wealth being partly derived from prostitution? During the five years after her marriage, Mary gave birth to two girls and a boy, each of whom died at birth or shortly after. One daughter, Phyllis, lived. About this, Ms. Quigley just writes: “As a respite from grief and malaise, she bolted for the public realm.”

Perhaps Ms. Quigley, a journalist and lawyer herself, was less interested in her subject’s psyche than in her tireless organizational and advocacy work. Certainly, this study is quite thorough concerning the political figures and events of Mary’s lifetime—sixty years of which were lived in Washington D.C.--and the many civil rights court cases, whether or not she or her husband, Robert H. Terrell, a longtime federal judge, were involved.

Particularly keen on contrasting the styles and philosophies of Supreme Court Justices William O. Douglas and Felix Frankfurter, Quigley also details much of what HUAC and other repressive government agencies were up to: particularly targeting Black leaders like Paul Robeson, Langston Hughes, and W.E.B. Dubois. She sensitively traces Mary’s attempts both to distance herself from “the taint of communism,” while supporting the free speech rights of these significant leaders.

Mary’s life was long, and her many contributions are meticulously detailed. Some major achievements: a charter member of the NAACP, she also helped found the National Association of Colored Women, serving as its first president, and was a founding member of the National Association of College Women. In her mid-80s, Mary was instrumental in the sit-ins and picketing which finally desegregated Washington’s restaurants and chain stores.

At age six, Mary’s mother sent her to live with a family in Yellow Springs, Ohio, to attend a school affiliated with Antioch College. She rarely saw her parents during those years. Around age ten, Mary transferred to a public school in Oberlin, Ohio, where free slaves settled and thrived. A hotbed of abolitionism, the whole community had functioned as an Underground Railroad station, with residents, sometimes facing armed resistance, often smuggling slaves into Canada.

In 1880, Mary enrolled in Oberlin College: this first coeducational institution, established in 1833, began accepting African American students two years later. When she matriculated, sixty-three African Americans already numbered among the college’s alumni, including thirty women. Studying Latin, German and Greek, Mary sat on the editorial board of the Oberlin Review, wrote poetry and “penned essays about the urban poor and prejudice…with thoughts that seemed to pour from her pen.” A classics major, she went on to get a Master’s degree in education.

After graduation (which both parents skipped), “Mary found herself an outlier with a suitor-deflating interest in philosophy and mathematics.” Her parents subsidized a two year stay in Europe where she honed her skills in German, French and Italian. At first she was alarmed at Robert Terrell “bombarding” her with letters. Claiming Mary’s letters were the most interesting he’d ever seen, Terrell urged her to consider a career in journalism. Throughout her life, she did frequently publish in periodicals, and ultimately a memoir, but was never satisfied with her own writing style.

Mary and Robert Terrell had met when they both taught at the Preparatory High School in D.C., the first African American public high school in the nation. Terrell was a subject of local pride: a native son who’d attended Harvard. He taught French, Latin and geometry; she worked as his assistant in the Latin department.

Returning from Europe, and “apparently to R.H. Terrell” (they married in 1891), Mary taught German and Latin at the Preparatory High School after Terrell had been principal. Then, he was ensconced in the Treasury Department.

Born in rural Virginia in 1857, Terrell never discussed whether he’d been a slave, though Quigley speculates “it seems likely he was.” Apparently experiencing cruelty as a child, one anecdote involved his grandmother “whipping him until he passed out…and kept beating him till he regained consciousness.” The family moved to Washington, and Robert attended the capital’s segregated public schools, until age 16 when he “fled to Boston and landed inside Harvard’s dining hall where students encouraged him to continue his studies.”

Five years later, Terrell enrolled in the prep school, Lawrence Academy, and the following year at Harvard. The year before he was tapped to be a speaker at his commencement, the Supreme Court undid much of the progress of the Reconstruction era, invalidating the Civil Rights Act of 1875: a federal law banning racial discrimination in public transportation and accommodations, including hotels and theaters. The court declared Congress had gone too far: the 14thAmendment “only authorized that body to remedy due process and equal protection violations wrought by state laws and state officials.”

While Mary was roaming through Europe, Robert had been “slogging through equity jurisprudence at Howard University.” In his valedictorian speech to his law school class, Terrell stressed the importance of “rectitude” for men of character—his mentor, Frederick Douglass sat on center stage. Aiming for a position in the Treasury Department, “with the finesse of a Washington insider,” Terrell enlisted the aid of Harvard alumni like Henry Cabot Lodge.

Throughout his career, Terrell skillfully used his Harvard connections. In 1901, he and his allies, including Booker T. Washington, successfully lobbied President Theodore Roosevelt, a fellow Harvard alumnus, to appoint Terrell to one of ten justice of the peace vacancies in the capital. “True to his class and his pedigree,” Quigley writes, “Roosevelt viewed African Americans as inferior to whites…but worthy blacks deserved to be recognized.”

Both of Terrell’s allies “relegated African Americans, at least for the foreseeable future, to a subordinate role (where as a matter of biology and culture, most of them belonged, Roosevelt believed).” In a column for the New York Age, Booker T. Washington, president of the Tuskegee Institute which famously emphasized practical training in manual trades and agricultural skills, had written that most whites never encountered “the higher and better class” of African Americans, while the “Negro loafer, gambler, and drunkard can be seen without social contact.”

At the International Congress of Women, a two week convocation in Berlin, Mary delivered her views on African American women in English and in German; in a separate appearance she spoke in French. Being treated with “perfect social equality,” Mary became more dissatisfied after Europe.

In 1905, almost three dozen intellectuals converged on a hotel in Ontario, Canada, summoned by W.E.B. Du Bois, who a decade earlier had received a Ph.D. from Harvard (admitting him only after he’d done graduate work in history and economics at the University of Berlin). Invoking the legacy of Frederick Douglass, Du Bois rejected Booker T. Washington’s “attitude of adjustment and submission.” Black American men had a duty to “insist” on full citizenship, he wrote, as envisioned by the Declaration of Independence.

Although happily married, Mary’s leanings were less establishment-oriented than her husband’s, who, unlike federal judges, held his post for only four years, and was at the mercy of the president. Hearing Du Bois speak at the Metropolitan AME church, his “sense of impatience resonated with Mary, and in spite of her husband’s allegiance to Washington, her conduct began to betray hints of her sympathies,” which were greatly inflamed by the 1906 Brownville, Texas race riots.

Erupting near Fort Brown, where African American infantry soldiers were stationed, “A haze of ambiguity cloaked the underlying events,” in which a white bartender and a police officer died. Allegedly instigated by armed Black troops, The Washington Post quoted a Houston paper’s reference to the soldiers as “black ruffians and brutes.” The next day, it was reported, residents purchased more than four hundred rifles and erected a “citizens’ guard” between the city and the fort.

But the troops’ white commanding officer vouched for their whereabouts at the time of the disorder. Spent army rifle shells—proffered as proof of guilt—could have been planted. Earlier that month, the commander of the army’s Southwest Division had relayed a warning to the War Department: Brownsville citizens harbored “race hated to an extreme degree.”

Nevertheless, four weeks later, Roosevelt discharged “without honor” 167 African American soldiers, barring them from further service in any branch of the military. And with “severity and breadth that puzzled major metropolitan dailies,” he also prevented them from ever again working for the government even in civilian jobs. Releasing his discharge order after the midterm congressional election was Roosevelt’s “effort to forestall adverse publicity and hold onto the black vote.”

The army never granted the Black soldiers a hearing, trial, or a court-martial proceeding. On the day after the first discharge papers went out, Mary beseeched William Howard Taft, War Department chief, to suspend Roosevelt’s mandate until the troops could stand trial. The next day, newspapers from Atlanta to Providence, “trumpeted Mary Church Terrell and her session with Taft”; the New York Times calling her “one of the leading colored educators of the country.”

Mary and W.E.B. Du Bois broadcast their dissatisfaction with Roosevelt in the Voice, a Chicago-based monthly magazine. “The president had earned the distrust and disapprobation of the best class of black men,” wrote Du Bois, urging all Black males to “insist” on justice for the Brownsville troops. Trying to put a positive spin on the incident, Mary noted it had united American Blacks, and “filled the whole race with grief as an evil out of which good will eventually come.”

In August 1907, Mary placed an article about convict labor in a British magazine, explaining chain gangs in detail. Detained on ”trumped up charges,” thousands of African Americans were confined to cells, undernourished, overworked, and “only partially covered with vermin-infested rags.” Several weeks later, she received a letter from a grandson of the abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison; Oswald Garrison Villard had been railing against peonage almost weekly in his publication, the New York Post.

Like Mary, Villard soured on Booker T. Washington after Brownsville. Mary’s husband continued defending his patron as “the great leader of his race.” But Mary was more inclined toward ViIlard’s call for resistance than Washington’s implicit embrace of patience—his plea for Blacks to demonstrate their worthiness as a condition of equality.

Mary’s status as a race spokesperson kept improving among progressives who paid to hear her on the lecture circuit. At the same time, she found herself marginalized by Booker T. Washington’s supporters, including those in the Black press. Robert sent William H. Taft a congratulatory letter after defeating William Jennings Bryan in the presidential election, suggesting Brownsville—such a preoccupation with his wife—had been all but forgotten. Stating, “I know that the colored people of the country are happy over your election,” Robert received a response appointing him to Taft’s Inaugural Committee; his judicial position was soon renewed.

Proving to be even less progressive about race relations than his predecessor, Taft quickly nominated a white man to serve as the collector of the port of Charleston—a position previously occupied by a Black man. It became known the Taft administration would not appoint or retain any African men in the South. Three weeks before Taft’s inauguration, the newly formed NAACP passed resolutions criticizing him.

Nationwide backlash against Blacks manifested itself in other [sick] ways. Later that year, a group of Galveston, Texas residents planned to publicly finance a $500,000 memorial to “mammy.” Supporting resolutions hailed “mammy” as “one of the grandest characters” in world history, known for her “pure, unselfish and unfaltering devotion.” Less than two weeks later, the Washington Post ran an editorial—reprinted from the New York Sun--calling for the monument’s construction in the nation’s capital.

The Post’s [deathless] prose suggested: “To Southerners, whether we refer to those still living South, or to the countless thousands who are now distributed all over the North, the East, and the West, hers is a name to conjure with. [voodoo, anyone?] White aproned, turbaned, always devoted and alert, she nursed a strenuous and proud race [sic] through the ailments and vicissitudes of childhood.” The Terrells responded with a blend of flight to Martha’s Vineyard, bullishness, and private alarm.

Robert, meanwhile, embarked on a lecture tour of the Midwest where he sounded his usual themes: thrift, hard work, frugality. “Optimism has been the saving grace of the Black man in this country.” While privately expressing doubts about Taft to Booker T. Washington, Robert’s speeches defended the president, explaining he was a misunderstood friend of African Americans.

Speaking to the graduating class of students at Howard University Law School where he’d been appointed by the board to teach, Terrell continued to publicly impart a message of hope. But Quigley asserts, “Robert knew that he and his generation had failed…to vanquish racial injustice, they had settled for tenure in the so-called Black Cabinet, as the Afro American newspaper dubbed Taft’s black loyalists.”

Mary decamped to Oberlin with her daughter, Phyllis, and Mary, the niece the Terrells raised, where she hoped the girls would benefit from a climate of intellectual and moral development. Instead, citing a housing shortage for undergrad students, her alma mater relegated the girls to a segregated boarding house. “Now parted all but officially, Mary and Robert still corresponded on a regular basis.”

In Washington, the horizon for African Americans kept shrinking with the election of Woodrow Wilson, a Virginia native who’d campaigned as a man of the people, a progressive alternative to Teddy Roosevelt, running on a third party ticket. With Democrats in control of both houses of Congress, southerners dominating Wilson’s cabinet harbored an agenda for D.C.: segregate its streetcars, prohibit interracial marriage, and terminate all Black appointees.

Timothy Egan, who writes about the havoc D.W Griffith, son of a Confederate Colonel, wreaked on race relations with his epic 1915 film, Birth of a Nation, also describes Woodrow Wilson as “a loathsome soul about race”: pointing out words from Wilson’s five-volume history were used as a title card in the film, “lending presidential authority to this rewrite of a nation.”

Mary’s husband’s job was in jeopardy, and she returned to D.C.; living separately, she successfully advocated for his reappointment. Fourteen months later, she left town again. Returning in 1916, “the effects of the new segregation reverberated in the capital and across the nation.” The War Department had issued a directive segregating the armed forces by race. Feeling the impact personally for the first time, Mary was denied service in a local D.C. chain drug store.

“For Robert, what had happened to Mary at People’s Drug Store served as a jolt and a turning point.” The incident “apparently reconciled” the Terrells. In a rare double appearance, both were on the program when, after Booker T. Washington’s death, Joel Spingarn, one of NACCP’s white leaders--the son of an Austrian Jewish tobacco merchant, who’d studied at Harvard and Columbia, a former chairman of their comp. lit department--hosted a conference of African American leaders in an attempt “to bridge the chasm between Washington’s supporters and the NAACP.”

After the U.S. entered WW1 in 1917, some 370,000 African Americans served in the military, more than half of them in France. Both Robert and Mary Terrell believed, and spoke about, the war yielding “dividends at home,” Quigley writes, “including freedom for all, irrespective of race and color.” [dream on, O ye wealthy ones!] Almost as soon as the war ended, the backlash began. Throughout the summer and fall of 1919, racial violence exploded in more than two dozen cities.

A mob of white servicemen amassed after nightfall near the White House, on July 19, 1919. “Murder Bay,” the nearby neighborhood, was renowned since before the Civil War for its gambling dens, brothels and allure to servicemen. Prohibition, job and housing shortages, and an onslaught of seventeen-year locusts already saw “a capital stewing in misery.”

Washington’s white newspapers had featured stories for several weeks about Blacks attacking white women. Those dailies, the NAACP warned, were “sowing the seeds of a race riot.” They lobbied Attorney General Palmer to prosecute the Washington Post for inciting a riot.

For several more nights, a throng of soldiers, marines, sailors and civilians roamed the mall and stormed the city’s main streets, armed with clubs: bashing in the head of a Black man with a brick; assaulting African American men on the streets, sometimes right outside the White House; and dragging them off streetcars.

Then some African Americans fought back. Inside a streetcar, one man pulled out a revolver and started shooting, wounding two soldiers and killing a civilian. Two blocks away on another streetcar, a man “aimed through a window and emptied his firearm into a crowd of jeering whites.” An African American man leaned out another window and shot a group of soldiers, wounding one. And a seventeen-year old girl allegedly shot and killed a police detective.

Consequently, an estimated 2,000 federal troops descended on Washington. A makeshift arsenal arose, stocked with more than 1,000 army-issue Colt 45 revolvers and more than 20,000 rounds of ammunition. Once the violence was quelled, the “editorial pages of the media now weighed in.”

Bemoaning the “demise of pre-war Washington, with its small-town placidity and well-behaved, law-abiding African Americans,” a New York Times editorial lamented, “Most of them admitted the superiority of the white race, and troubles between the two races were unheard of.”

Robert Terrell’s criticisms became more severe and pointed, blaming white servicemen in D.C. who had “run amok through the streets of the National Capital.” After the violence, he wrote, it was “our duty to contend and contend, to protest and protest…for a fair and square deal.” Adding, “Black men do not come begging: they come standing erect, demanding their just share of the fruits of war as American citizens.”

From that point, until Terrell, who was in ill health, died of a cerebral hemorrhage in 1925 at age sixty-eight, his relations with his wife were on and off again. Just two weeks after the war ended, Mary took a job with the War Department, which seemed to mostly involve tirelessly advocating, especially among newly enfranchised Black women, for the election of Warren G. Harding, whose campaign embraced antilynching legislation, and broad proclamations about equality.

However, in his inaugural speech which pledged to initiate “an era of good feeling,” Harding reiterated his “campaign themes of isolationism, convention, and thrift”—with no reference to a federal public welfare department, no promise to appoint a woman in his cabinet, and no mention of antilynching legislation or equal rights for African Americans.

Three months later, the Associated Negro Press, a news service for Black publications, grilled a Justice Dept. official about placards in their building denoting whites-only men’s rooms. Feigning ignorance, he then responded, since whites hadn’t complained, he saw no basis for an objection. When the proposed “Black Mammy” statue resurfaced due to the Daughters of the Confederacy, with the Senate’s blessing, Mary wrote letters to major newspapers, pointing out the obvious: enslaved Black women had no homes of their own, no legal rights to marriage, and their own children were often sold away.

Joining Black leaders in a meeting with the War Department secretary to decry a segregated bathing area at the tidal basin near the Lincoln Memorial, her disenchantment with Harding was complete when the Memorial was dedicated in 1922. The invited Black luminaries were directed to a segregated area. Most “felt compelled to leave to avoid the humiliation of sitting in a Jim Crow section.”

After Robert’s death, Mary began writing her memoir which she’d been yearning to do for decades. Receiving some initial encouragement from Little, Brown & Co., both Mary and the editors were dissatisfied with her drafts. H.G. Wells was not encouraging either, when Mary met with him. Nine years later, she decided to release the book on her own through Randall Inc., a publisher and printer of books, magazines and catalogs whose other titles included scholarly, legal, and medical treatises.

Wells agreed to write the Introduction, but he “had not raved about her effort.” As much as he liked her, and admired Mary’s many achievements, he wrote, her book was “artless,” a “loose and ample assemblage of reminiscences of very unequal value.” In an undated typed note from early in the process, Mary stated her intention not to explore in-depth the “obstacles” and “barriers” she’d encountered because of race, opting instead to focus on “opportunities.” Over time, she excised potentially telling details in various drafts of the book. The memoir had little impact.

My own quick perusal of A Colored Woman in a White World, reprinted by The National Association of Colored Women’s Clubs in 1968, was a bit like reading a long, impressive, but rather tedious list: Mary (called Molly by all) goes into some detail about each house the family bought and furnished, the preserves she put up, the many institutions and clubs she spoke at, especially for women’s suffrage, the people she met, her organizational work, and multitudinous court cases. She refers to her husband throughout as Judge Terrell.

Discussing her political activities, she offers rather hollow topic sentences, like “Having observed from attending the Woman Suffrage meetings how much may be accomplished through organization, I entered enthusiastically into clubwork among the women of my own group.” Although this kind of opener might be followed by vivid, personal anecdotes, it isn’t. Similarly, on her family: “I enjoyed my children thoroughly while they were growing up, and spent as much time with them as I possibly could.” (Some of which--when they went to the movies and theater—was spent passing.)

The most poignant paragraph, to my mind, is a kind of meta-comment on her book, and her life. “If I had lived in a literary atmosphere, or if my time had not been so completely occupied with public work of many varieties, I might have gratified my desire to ‘tell the world’ a few things I wanted it to know…I can not help wondering whether I might not have succeeded as a short-story writer, or a novelist, or an essayist, if the conditions under which I lived had been more conducive to the kind of literary work I longed to do.”

During the Depression, real estate values plummeted, so did the income from her inheritance, tied up in Memphis properties. In 1931, Mary divided up into apartments her S Street row house (which the agent had initially refused to sell her, until she agreed to pay several thousand dollars over the asking price and to make a larger down payment): installing herself on the ground floor, with her divorced daughter, Phyllis, who slept on the day bed in the library.

Mary also became involved with a Chicago Republican, married and seven years her junior: the first African American congressman elected in the twentieth century and the first elected in the North. “Like a much younger woman afflicted with a crush, she kept track of when he called…and when he admired her appearance at a reception.” The liaison ended two years later, with Mary expressing relief. ”Months after that, she bristled at his refusal to lend her a typewriter.”

Before WW II, Roosevelt, “with little fanfare,” desegregated the federal workforce: following concerted agitation by labor activists, particularly A. Philip Randolph, organizer and President of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters, the first successful African American-led labor union. Jim Crow restrictions were removed from most government cafeterias, as well as the capital’s federally controlled parks and recreation areas, including picnic grounds, golf and tennis facilities.

But three months after V-E Day, the Mississippi Democrat, Chair of the Senate’s Committee on the District of Columbia (thus, its unofficial mayor), called for construction of a Washington stadium with Jim Crow seating. Also claiming federal contributions to Howard University were unconstitutional, he reputedly complained to the police chief about Black motorcycle cops detaining white drivers.

This situation, along with the burgeoning House Committee on Un-American Activities, drove Mary to ease back into her activist role. She’d been deeply incensed by the actions of the Washington branch of the American Association of University Women which she’d applied to join in 1946. The only admission criterion was to hold a degree from an accredited university, nonetheless the eight-member executive committee voted unanimously to reject her.

In 1949, a three judge panel of the federal appeals court in Washington upheld the branch’s right to exclude African Americans. (When the national organization voted to accept qualified members regardless of race, the Washington branch seceded from the AAUW.)

At a time when CORE was forming, and many African American leaders were being vilified, a Chicago Defender columnist blasted HUAC. The article ended with a quote from Mary Terrell: “Suspected of ‘Communist’ is every colored person in America who believes in political and civil rights, and proposes to get them, and every white person who thinks he ought to.” (In 1949, the NAACP barred Communist-front entities from its upcoming civil rights mobilization in Washington.)

Mary decided not to attend the World Peace Congress in Paris where Paul Robeson numbered among the speakers. There, he proclaimed Black Americans would refuse to fight Russia on behalf of a government which had oppressed them for so long. Terrell, along with many Black leaders, distanced herself from this remark, fearing to be labeled a communist. She did sign a statement demanding Robeson’s right to speak and sing at a Negro Freedom Rally in D.C.

In text and lists in a 166-single-page report, HUAC named Mary Church Terrell five times. The committee did not suggest she was a known Communist Party member. Rather, they consigned her (along with W.E.B. Du Bois, and more than 50 others) to the ranks of “fellow travelers”: individuals affiliated with a significant number of Communist front organizations.

President Truman, wishing to secure the Black vote, pushed ahead on a civil rights agenda, finally issuing an executive order in 1948 mandating equal treatment and opportunities without regard to race, for all persons in the armed services. He also established a fair-employment policy for federal civil service workers. Still, a strong backlash existed in the nation’s capital; most private facilities remained segregated.

Meanwhile, the longstanding, insidious “separate but equal” doctrine was being eroded in several Supreme Court cases concerning the treatment of specific university and grad students; momentum was gathering for the landmark 1954 Brown v. Topeka, Kansas desegregation decision. Petitioning the United Nations about discrimination in the U.S., Mary remarked African Americans in Washington fared “no better” than Blacks in Georgia and Mississippi.

Later that month, at age 85, Mary agreed to serve as permanent chairman of the soon-to-be-highly-influential committee to revive the Reconstruction-era laws which had initially prohibited segregation in D.C. In 1949, while HUAC and McCarthy were going strong, the National Lawyers Guild, which HUAC had branded a Communist front organization, issued a legal opinion stating D.C.’s Reconstruction-era antidiscrimination ordinances remained “in effect and enforceable.”

Looking for a test case, Mary, with a Congregational Church pastor, and a member of the cafeteria workers union, returned to Thompson’s chain store for a second time, joined by a white friend. Only the white man was permitted to purchase something to eat. In March of that year, the Municipal Court convened a hearing in Mary’s case against Thompson’s.

A press release emanated from the Coordinating Committee for the Enforcement of the D.C. Anti-Discrimination Laws, operating “under Mary’s stewardship.” Summarizing the allegations against Thompson’s with the names and backgrounds of the four complaining witnesses, it also contained a statement from Mary, defending her own patriotism. Declaring those who were trying to enforce the Antidiscrimination laws “are rendering their country a great service. They are trying to stop it from being disgraced by preventing hotels and restaurants from refusing to serve colored people in the capital of what is called the greatest democracy on earth.”

The charges were dismissed; in essence, the judge found Thompson’s not guilty. With two compatriots, Mary returned for a third time, and again was refused service. An appeal was filed. On her eighty-seventh birthday, while an Afro-Americanphotographer hovered in the background, she coached volunteers about contesting segregated seating at dime stores.

On Christmas Eve, grabbing her cane and purse, Mary marched on a picket line outside Kresge’s, a five-and-ten-cent store. After the holidays, the Afro-American ran her photograph, clad in a winter coat and lace-up oxford heels, holding a placard that read, “Don’t Buy at Kresge’s—the only Jim Crow Dime Store on 7th Street.” Kresge’s quickly capitulated, announcing it would serve African Americans.

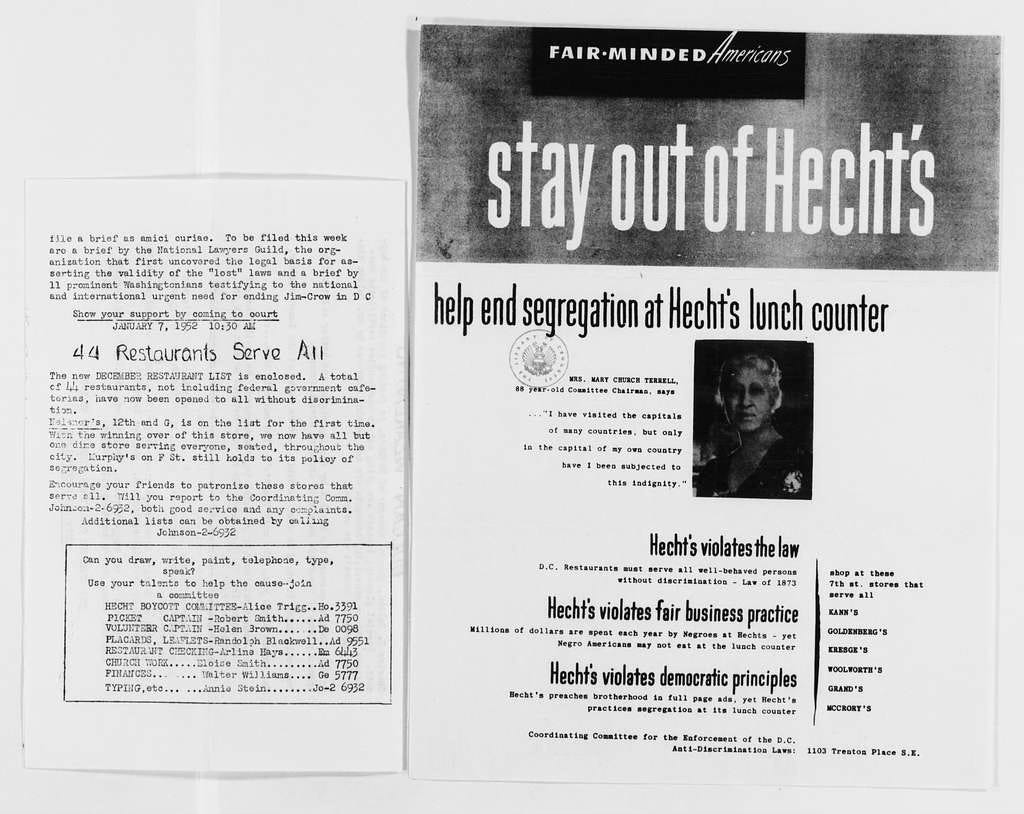

In May of 1951, a two-judge majority of the Municipal Court of Appeals upheld the validity of one of the Reconstruction-era antidiscrimination laws. Five days later, Mary and others met at the First Congregational Church to celebrate their victory, and to organize support for a four-week old boycott of Hecht’s, where management still refused to serve African Americans at the downtown store’s basement lunch counter.

They tacked on a protest against Vernon West, the District’s chief legal officer, who announced he would not enforce the antidiscrimination laws until litigants had exhausted their appeals. West had behaved like a dictator, Mary declared, one who could tutor Spain’s General Franco in autocracy’s nuances. His stance fueled resistance. Sixteen Blacks and four whites staged a three-hour protest at Hecht’s lunch counter, occupying stools while management ignored their presence and ordered African American waitresses not to serve them.

The Hecht’s boycott went on for eight months. Its financial impact could not be ignored, and two weeks before the end of its fiscal year, the store reversed their lunch-counter policy. “Based on her calendar, one might surmise that Mary Church Terrell was not well,” Quigley writes. “But…with the Hecht’s white sale in progress in all three stores, she radiated vitality. As she chatted with a reporter and ate her lunch, she distilled a lesson, as if reverting to her days as a teacher. ‘We’re second class citizens because we sit idly by.’”

During the Coordinating Committee’s two-year boycott of downtown five-and-ten cent stores, all but one of the chains, Murphy’s, yielded to integration. First, Mary wrote the company’s chairman, conveying her shock that a store with northern roots would be the last Jim Crow adherent. With the advent of the back-to-school shopping season, she sent a letter to local ministers, under the Coordinating Committee’s name, urging them to remind their congregations: “DON’T BUY EVEN ONE PENCIL AT MURPHY’S DIME STORE.”

With a group of clergymen, Mary picketed the store. She ”anchored the group, like a hinge. Alone among the participants she carried no sign. Instead, she balanced a purse in one hand and a cane in another.” Then with a children’s picket line planned for the coming Saturday, Murphy’s district manager agreed to integrate the store.

Of course, the backlash was immediate, led by Senator James O. Eastland, a Mississippi Democrat, and plantation owner who won his first full term in 1942 by vowing to prevent Blacks and whites from dining together in Washington. Sitting on the Judiciary Committee’s Internal Security Subcommittee, the Senate’s equivalent of HUAC, Eastland introduced a bill authorizing Congress to declare an internal security emergency. Bypassing the president, Attorney General McGrath would have power to detain anyone likely to commit sabotage.

Eastland, who was up for reelection in two years, claimed to have received “valuable information” that 20,000 Kremlin agents were already in the country, plotting its destruction. McGrath had already started taking preliminary steps to establish 3 facilities, with an estimated capacity of 3000, at 3 locations: a former military airport in Arizona; and two World War II era prison camps, there and in Oklahoma.

More serious backlash followed Mary’ public statement: “Today, every dime store in the city of Washington is serving everyone equally and peacefully, bringing closer the day” when one-third of its residents will be treated as first class citizens. Over the objections of the local NAACP, Truman signed a law expanding the Washington trespass statute, making it a misdemeanor to enter a public or private dwelling in the capital against the will of the person in charge, and remaining in place after being asked to leave.

Nevertheless, grateful for Truman’s civil rights advancements, during the 1952 presidential campaign, Mrs. Terrell switched from being a lifelong Republican to a Democrat. The newspaper, the Afro, learned that Nixon’s D.C. home contained a restrictive covenant prohibiting its sale to “persons of Negro blood or extraction,” including Jews, Armenians, Persians, and Syrians.

Three days later, the Afro took aim at Eisenhower, who was running as a war hero. Until his nomination, the paper reported, Ike had owned a partial stake in a D.C. Howard Johnson’s restaurant which had allegedly fired its night manager for serving two African Americans.

Dovetailing with the complex, and momentous Brown v. Topeka, Kansas lawsuit, the D.C. battle for desegregation went on for some time: a court case overturned the antidiscrimination laws, followed by a Supreme Court case seeking to reinstate them.

Eisenhower was of no help. In his first state of the Union address, he did not endorse –or even mention—federal civil rights legislation. Nor did he refer to the judiciary, across the street at the Supreme Court, where the justices were pondering the future of public education. Instead, Eisenhower “pledged to use the authority of his office to end segregation in the District of Columbia, including the federal government and the military. He received tepid applause.”

When the dust finally settled, the Afro’s banner headline proclaimed: “EAT ANYWHERE!” Filing into Thompson’s restaurant three days later, wearing a two-piece aqua suit and a red hat, the manager commandeered Mary’s tray and carried it into the dining room. “His gesture conveyed deference and respect, courtesies to which she had always thought herself entitled.” Inside the restaurant a photographer snapped Mary’s picture, surrounded by her repast.

The Afro ran the photograph four days later. Underneath was a separate story, in which Mary remarked, “I am greatly opposed to the Eisenhower administration taking credit for opening the restaurants. It had nothing to do with it.”

On her 90th birthday, Mary and several colleagues launched a drive to banish Jim Crow from the capital’s movie theaters. After lunch at Longchamps Restaurant, they were surprised to be admitted to the Loew’s Capital Theatre without objection. At Mary’s formal birthday reception, attended by more than 700 people, she announced every movie house in the capital was now open to customers without regard to race. The theater campaign had been the “shortest and pleasantest” of her career.

During the festivities, Mary posed for a photograph with Paul Robeson. He and his wife, Eslanda, had also sent written tributes to the luncheon committee, praising Mary for her leadership and perseverance. “Certainly no one in our contemporary life more exemplifies our courage, our integrity, our militant demands for full citizenship and full freedom,” he wrote.

Mary Church Terrell’s life began in the year of the Emancipation Proclamation and ended two months after Brown. In an Annapolis hospital, she died of cancer two months shy of her ninety-first birthday. More than 700 people were packed in the church, and loudspeakers transmitted the ceremony to the overflow crowd spilling into the Sunday school rooms, onto the front entrance, and into the street.

Ms. Quigley ends her book: “She had defied the capital’s entrenched southern culture, its deference to racial separatism and exclusion. With a pair of Reconstruction-era laws, with the Supreme Court’s intercession, she had prevailed, reshaping Washington’s image from Dixie backwater to global beacon, for all the people.”