Next year will be the twentieth anniversary of San Diego City Works Press. In the lead-up to this and the publication of Sunshine/Noir III: Writing from San Diego and Tijuana (in 2025), The Jumping-Off Place will be featuring some of the highlights from City Works Press’s many publications.

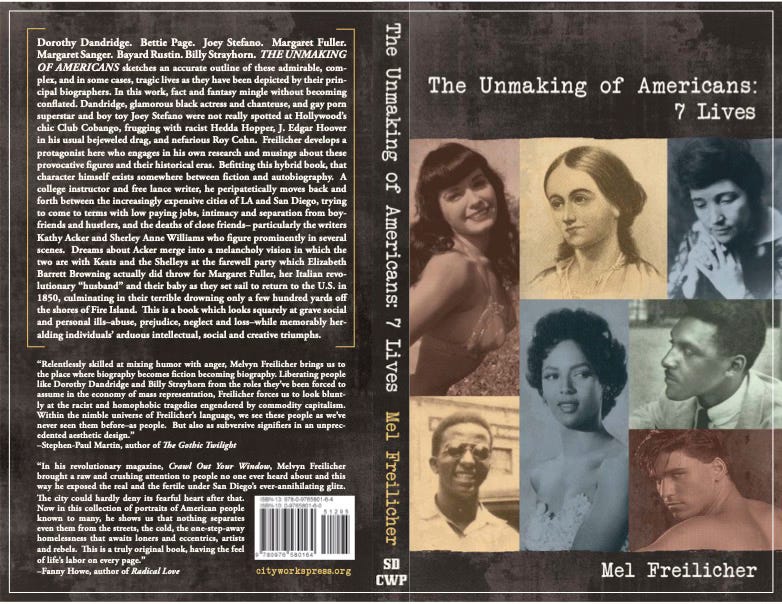

The The Unmaking of Americans: 7 Lives by Mel Freilicher can be purchased here. The selection below is the first part of Book 2: Two Margarets.

MARGARET FULLER: from Transcendentalism to revolution Paula Blanchard

Addison-Wesley, 1987

EMERSON AMONG THE ECCENTRICS: a group Portrait

Carlos Baker

Viking, 1996

WOMAN OF VALOR: margaret sanger and the Birth control movement in america Ellen Chesler

Anchor Books, 19921.

The Book and The Life

Paula Blanchard’s excellent study of Margaret Fuller reveals a fascinating and complex character: America’s foremost female intellectual and “woman of letters” of the 19th century (quite an oxymoronic notion then). Margaret was perceived as pedantic, plain (Oliver Wendell Holmes claimed she could resemble either a snake or swan, viewing her more as the former), competitive with men, and “unsexed”: “a legendary bogey- woman, symbolizing a threat not only to the male ego but to the family, and thus to social order.” The counter-coin-side was her reputation as a brilliant, witty and precise conversationalist—partly because, unlike many male counterparts, she actually responded to other speakers. Margaret’s conversation, Emerson said simply, was the most entertaining in America. After a solitary childhood, she happily developed a talent for friendship, becoming a popular house guest and always maintaining a voluminous correspondence.

These skills led Margaret to earn her living from 1839-42 by teaching some of the most prominent and educated New England women, in subscription series of private seminars, or Conversations. The idea arose, and the nucleus formed for the first series, after Margaret became the natural center of the Transcendentalist group meeting informally at the bookstore Elizabeth Peabody had interrupted her teaching career to open, which offered for sale German and French publications that could not be found elsewhere in Boston. The regulars were often joined by two rather silent visitors, Nathanael Hawthorne and Horace Mann, the educational reformer recently instrumental in founding a State Board of Education, who were both courting Elizabeth’s younger sister.

Whatever the topic of Margaret’s individual discourses, she consis- tently strived for women to alter their self-image, by understanding that inadequacies were “a result of superficial education and the attitude of self-deprecation instilled by social custom.” At the time, Fuller was the first editor of the Transcendentalists’ influential review, The Dial, and its greatest contributor, along with Theodore Parker and Emerson, her most valued friend. She had already held several teaching positions of languages, including in a Providence school founded by a disciple of the abolitionist Bronson Alcott, whose own school was closed by the Boston authorities in 1840, when he admitted a black pupil. (Neither her teaching position at Alcott’s Temple School nor the Dial ever ended up paying a cent; when Margaret resigned her editorship, Emerson declared “let there be rotation in martyrdom.”)

The “peculiar intermixture” of Margaret’s intellectual achievements and emotional evolution is particularly comparable to that of John Stuart Mill. Daughter of a former school teacher who was a Harvard gradu- ate, Margaret’s education was classical, rigorous and eclectic. By age 8, she had gone through Shakespeare, as well as Greek mythology, which brought on repeated, blood-drenched nightmares; at 9, Margaret was studying Virgil, Cicero, Livy and Tacitus. At 16, she was reading fluently in French, Italian, Latin and German: works by Petrarch, Dante, Milton, Racine, Epictetus, the romantic poets, Smollett. Margaret developed a lasting interest in Goethe, and began translating and writing about him. Praising contemporary, scandalous European women authors, Mme de Staël, George Sand and Mary Wollstonecraft, she went on to create a cornerstone of American feminist thinking, Woman in the Nineteenth Century, replete with classical paradigms and erudite literary allusions, underscoring her analysis of contemporary women’s customary and legalized servitude in marriage. Drawing on the familiar Transcendentalist theme of self-reliance, Margaret advocated celibacy until a woman became strong enough to choose freely whether or not to marry.

Margaret’s other major writings developed from changing loca- tions and occupations. In the summer of 1843, she and a friend Sarah Clarke set out on a tour of what was still known as the American Northwest—Chicago, Milwaukee, and surrounding countryside: her meticu- lous journal eventually became a book. Summer on the Lakes is a light but penetrating look into an ephemeral period in the history of the Great Lakes region, when the many diverse settlers, Norwegians, Germans, English, Irish, Welsh, remained in separate, homogeneous cultural oases. Margaret described the “generous, elemental landscape” in sharp con- trast to the squalid ugliness and petty greed of the cities; she painted a disturbing picture of misplaced European city dweller settlers, and ruth- less displacement of the Indians.

Margaret’s reputation as a condescending and airy Transcendentalist notwithstanding, she worked very hard to help support her large family, and to assist the youngest of five brothers who was slightly mentally retarded to live independently as an adult, for one period at Brook Farm colony (Emerson also had a developmentally disabled younger brother, as did Walt Whitman).

In the country, at Groton, in 1832, she spent five to eight hours a day tutoring disinterested siblings, while helping in the “numbing routine” of enormous amounts of housework, particularly because her mother was often ill. She nursed her grandmother and two baby brothers, one of whom died in her arms. Later that year, her father died, too. As the eldest child, a thoroughly inexperienced Margaret had to disentangle his unfortunate financial affairs—the money was mostly tied up in unpro- ductive real estate.

Later, Margaret moved to New York, and began a journalistic career. Horace Greeley, bohemian editor of the crusading New York Tribune, deeply admired Woman in the Nineteenth Century which was much talked about then; his wife had been an active participant in Margaret’s Conversations in the Boston area. Greeley hired Margaret as literary editor: her reviews on theology, poetry, fiction, philosophy and history appeared on the front page. Greeley soon commissioned Margaret to do a series of articles on New York’s philanthropic institutions. Fifth largest city in the world, New York boasted an admirable public transportation system, gaslights, a new water works, and an extensive network of insti- tutions for the disadvantaged. Margaret visited Sing Sing prison and the Bloomingdale Asylum for the Insane twice each, hospitals, orphanages, almshouses; she interviewed prostitutes in the Tombs, City jail. While depicting the Bloomingdale Asylum as a model of its kind, she refused to flatter New York civic pride, describing other establishments, along with local slums, in grimly dehumanizing terms.

Biographers tend to view Greeley as having saved Margaret from the “Never-Never-Land of Boston Transcendentalism,” despite the fact that her companion on most of these visits was Boston Brahman William Channing, an ardent socialist and labor reformer. Margaret’s last few years were lived in Europe, as correspondent for the New York Tribune, while simultaneous revolutions were erupting: she became well acquainted with Elizabeth Barrett Browning, Thomas Carlyle, George Sand, Chopin, the Polish patriot and leading epic poet, Adam Mickiewicz. Eyewitness to fervent revolutionary struggles, Margaret sent urgent and eloquent dispatches from besieged Rome during the 1848 uprising, where the Italian nationalist hero Giuseppe Mazzini was a very close friend; she was also writing a book about these events as they unfolded.

As independent thinker, Margaret was heir presumptive: both her grandfather and father had been rebellious intellectuals. The grandfather, Timothy Fuller, a minister without a congregation, was a respected delegate from Philadelphia to the Constitutional Convention in 1787: he refused to ratify the Constitution because it condoned slavery. Margaret’s father, Timothy Jr., one of eleven children, was a debater at Harvard, elected to Phi Beta Kappa, and earned “something of a reputation as a gadfly,” leading student protests against arbitrary college rules. There, young Fuller was a Unitarian among Congregationalists, a Jeffersonian Republican among Federalists, and an abolitionist among wealthy young men whose families owed much to slavery. His political beliefs cost him several potential lucrative jobs; later he was elected to the Massachusetts legislature, and four terms to Congress.

Just at the onset of her rigorous education, a sister Adelaide, two years younger, suddenly died, and Margaret was left to bear the full brunt of her father’s keen pedagogical ambitions. But as she grew older, he began warning about “immoderate indulgence” in reading, and pushed Margaret to learn the virtues of husband-procuring. She then developed symptoms which continued throughout her life: becoming melancholic, priggish, subject to violent tantrums. In conversation, she typically combined haughtiness with absolute candor. Emerson claimed that Marga- ret had no instinct for humility, and referred to her as “this imperious dame.” The adult Margaret was frequently depressed, experiencing periods of lassitude and morbid religiosity, of which only her closest friends were aware.

Accepting the notion that it was impossible for her to be fulfilled both as a woman and a thinker, Margaret voluntarily denied her own interests in a number of younger men. She “assumed the mask of the brisk, self- reliant, neutered being,” while dispensing “sisterly advice to her lovelorn friends.” Compelled to periodically renew “vows of renunciation” in the face of the “quasi-erotic intensity of her friendships with both sexes,” only in Europe did Margaret gloriously transcend that pattern: in Rome, she took a lover and had his child. Giovanni Ossoli was 26 when he met Margaret and spoke no English; he was tall and slightly built, good- looking, with a serious expression. The Ossolis were an ancient family of modest fortune which for generations had been in service of the papacy: his father had been an official at the Vatican before falling ill. Giovanni was “bred as a gentleman and indifferently educated, he was fit for no profession but the Army.” There’s no direct evidence that she and Ossoli ever married, but they remained a devoted couple. Reserved and self- sufficient, he respected, and was content to stay apart from, Margaret’s intellectual work. A fierce Republican, Ossoli joined the civic guards, and was expecting to be killed when the French came in to put down the Roman triumvirate, led by Mazzini.

At age 38, Margaret went off to a village in the Abruzzi mountains, about 50 miles northeast of Rome, to have her baby. She explored the beautiful countryside alone, and continued to work on her book. But Margaret felt increasingly isolated, often unwell, the mail was censored, and she feared the Neapolitan soldiers who were swaggering about town: on their way to put down the liberals in Naples, they began warming up by arresting six there. She reluctantly left the baby, Angelo, with a wet nurse and returned to Rome, where revolutionary turmoil was rapidly accelerating. Margaret became director of one of the hospitals which her friend, the Princess Cristina Belgiojoso started in abandoned ecclesiastical buildings (her own properties had been confiscated); after political exile, the princess organized her tenant farmers into a cooperative community, and built new housing, a school and a recreation center.

The couple finally decided on the necessity of leaving Italy, hoping to return in a few years. Exhausted, they made their way to England. Margaret went about preparing for a two-month sea voyage under a cloud of apprehension brought about by a prolonged headache. She saw evil omens everywhere. A steamer and sailing packet had recently been wrecked: both were reputedly safer than the merchant ship, Elizabeth, on which they were booked. They spent their last night in England with the Brownings, who teased Ossoli about a prophecy that he should fear death by water.

On the Elizabeth, their child became very sick, as he had once been in the mountains. Despite Margaret’s characteristic fatalism, she again skillfully nursed Nino back to health. The Elizabeth came in sight of Fire Island, when it ran aground on a sand bar: the violence of the blow drove the cargo of marble through the ship’s hull, flooding the hold. With the beach only a few hundred yards away, they awaited rescue. Although scavengers were visible on shore, there was never any sign of the rescue boat. Twelve hours later, a mountainous wave broke over the vessel, carrying away its mast and everybody who remained on board. Nino’s body appeared on the beach a few minutes later; Margaret’s and Ossoli’s were never found. When news of the wreck reached Massachusetts, her brother-in-law Ellery Channing and Thoreau went to Fire Island for a week, to search for their bodies and personal effects.

2.

WHAT MAKES MARGARET RUN?

When Peripatetic Book Reviewer sleepily read his e-mail that hazy morning, he would have fallen right back asleep had he realized this would one day result in trading salty Fuller stories with crusty old coots at chic Cancun. In fact, P B-R believed he’d been asked to a symposium to help resuscitate Budd Schulberg’s reputation, in which he (Aged One) played some small role long ago, having written his dissertation on social realism and the Hollywood dream machine. True, it was his policy to accept all free trips, but later P B-R realized that he had acted mostly out of nostalgia for an earlier phase of his own erstwhile career: when he still thought it possible to become a more or less established, if distinctly unspecialized, academic.

Budd Schulberg, you may recall, son of B.P. Schulberg, an original Hollywood mogul, was better known for his novels, What Makes Sammy Run? and The Disenchanted (about F. Scott Fitzgerald’s last years) than screenplays. Schulberg, a left-liberal-anti-communist named 15 fellow Party members at the McCarthy hearings. Until he resigned in 1940, the Communist Party tried to shape his writings to become “useful weapons” as “proletarian novels.” He’s one of the few friendly witnesses that P B-R has found it in his none too capacious heart to forgive, chiefly because Schulberg cited the fate of the extraordinary Russian writer Isaac Babel as a primary reason for testifying. (A year later he wrote an article for Sat- urday Review, which discussed how the great Russian director Meyerhold was arrested and vanished, subsequent to a courageous public speech in 1939, also how Gorky died under mysterious circumstances, in 1936.)

Schulberg related that when he went, an avowed Young Communist, to the Writers Congress in 1934 in the Soviet Union, Isaac Babel spoke publicly for the first time since 1928: he was clinging to the right to write badly, which Schulberg didn’t understand then. Eventually, every one of the speakers at that Congress was liquidated. Further, when Schulberg confronted Lillian Hellman about Babel’s fate—he had fought in the Russian Revolution, only to be killed later in a Stalinist death camp—she responded, “Prove it!” Schulberg went on to write the screenplays for A Face in the Crowd and On the Waterfront (which exonerates “snitching” and was directed by Elia Kazan, another notorious friendly witness). Continuing to write, in 1964 Schulberg helped found the Watts Writers Workshop where he remained active.

Not until re-reading his e-mail several days later did Book Reviewer realize the conference didn’t concern Schulberg at all; luckily, that message was still in his trash, along with the computer dating service’s demand to pay the bill and immediately cease his heartless lying. Too late! P B-R had already wired his agreement to appear (shut)—not to mention pre-spending the meager honorarium toward a shiny new root canal. Although he didn’t know exactly who had invited him to this “WHAT MADE MARGARET RUN?” symposium, P B-R presumed it was due to his recent research on female abolitionists in relation to the Transcendentalists: his article had focussed on the violent, large scale uprisings against returning the slave Anthony Burns, who was hunted down in Boston in 1854. At the Framingham Independence Day cele- brations, Quaker activist Abby Kelley Foster, Sojourner Truth, Thoreau, William Lloyd Garrison and others argued for massive disobedience to the Fugitive Slave Law.

So, in true, erratic scholarly fashion, P B-R began to read and ponder Margaret Fuller’s fascinating life and career, whereas previously she’d been an occasional side dish to Thoreau’s tender thorns. Soon P B-R believed that he could whip out a pertinent little paper. He knew Fuller had become a full-blown abolitionist only after she left the country, and witnessed the European revolutions: formerly, she and her father had both advocated the gradual phasing-out of slavery, much to the distress of her close friend, Lydia Maria Child, editor of the National Anti-Slavery Standard.

The more P B-R pondered, the more ponderous he became, until he felt like he resembled a bloated Emerson. Scarcely anyone could comprehend this man in the supermarket, or abroad. Nevertheless, he stood as he would. Typically, at the conference itself, P B-R managed to emit cogent remarks, sometimes posing as Mrs. Margaret Mytholee of Ithaca, or else Oliver de Prongh, self-styled “universal live-wire, ex Eye-Ball, etc.”: mainly de Prongh materialized to cruise ladies of both sexes at Cancun Hilton’s decidedly cocky Cukaracha club.

Overhearing vague talk that a subsequent conference might occur in idyllic Vancouver, on the plane home P B-R quickly began jotting down a list for future thought, and possible articles (hopefully not for academic journals): “WHAT IS TO BE LEARNED?” Number one: the high infant and childhood mortality rate. How could Margaret’s generation stand that awful fact of life? Another major issue concerned how similar Margaret’s familial patterns were to other exceptional women’s (and not just from her own generation)—feminists, abolitionists, Socialists, labor organizers. For instance, to Margaret Sanger and Simone de Beauvoir: all had domesticated and supportive mothers along with strongly intellectual, individualist fathers whose financial losses exposed unanticipated inadequacies; adoring daughters precariously thrust into position to cope with harsh exigencies. Although most biographers believe that Margaret’s own pious mother exerted little influence, Blanchard sees Margaret Crane Fuller as imparting many domestic skills, and the love of her garden, to her daughter.

One definite psychographic area for someone to bubble around in is Margaret’s significant attachments to a number of older women (not to mention younger men!): beginning at age 7 when she developed a strong devotion to Ellen Kilshaw, a visitor from Liverpool; Margaret’s parents were hoping Ellen would remain to become her teacher. A model of British good taste and poise, Ellen played the harp and painted in oils. At age 25, Margaret was fortunate to become the protégée of Mrs. Eliza Rotch Farrar, a handsome woman in her forties, second wife of JohnFarrar, professor of mathematics and natural philosophy at Harvard who introduced Margaret to Cambridge society, offering her a second home. The maternal Eliza Farrar helped to transform Margaret into a poised and graceful young lady, supervising her hairdresser and seamstress; within a few years, Margaret had earned a reputation for irreproachable taste in clothes. She finally met Emerson in 1836 at the Farrars’ soiree for Harriet Martineau, the English Unitarian and writer of semifictional books on social reform. Eliza Farrar’s autobiography, published at age 75, revealed a history of transAtlantic connections: as a young girl she had known Lord Nelson and Lady Hamilton, Maria Edgeworth, Mrs. Siddons the actress, and had once been at a salon of the famous beauty, Madame Recamier (whose ardent relationship with Madame de Staël Margaret wrote about, and wished to emulate in similar relationships with women).

Peripatetic Book Reviewer barely got a chance to expand his original list of topics, let alone do any pondering, before summer was a fluky memory—actually, the month long trip to the east coast didn’t leave much time or money. Now that the new semester was unrelentingly puff- ing away, Peripatetic One felt like he might as well be teaching ancient Finnish epics to over-age, pre-operative pundits. Plus, he had foolishly dreamed of designating whole juicy research areas to particular juicy grad students. If only he hadn’t abdicated his cushy tenured position in cultural anthropology at Harvard to take that perilous plunge into tin stars in a small mining college in suburban Colorado (mumbling some- thing about an LSD experience in which he truly grasped the meaning of “academic freedom”), he could still have grad students galore to mop up the blood, dutifully worshipping every desultory drip.

3.

A LITERARY LI(F)E

Back in San Diego (“oy, homebase”) to teach his standard “new journalism” courses, P B-R was ruminating that although he’d eagerly left a too provincial feeling Colorado only a few weeks before, it already seemed like a lifetime—at least he wasn’t run out of town, like in unspeakable Duluth. (How had that spotted cow gotten into his studio, anyhow?) Upon returning, P B-R promptly learnt that Anne was dying of cancer; she’d been sick the past year, without anybody at school appearing to know much about it. Close friends many years ago, still with a strong affinity, P B-R called several times; they gossiped and laughed, but when he said he wanted to visit, Anne replied, “Please don’t”—no possibility of laughter there.

P B-R had many intimates who had died of AIDS or cancer, of course, but none in the past two years. Trying not to dwell on any of this (despite those individuals being on his mind almost daily), P B-R began casting around for a diverting and manageable writing project: he got an idea when some friends, who came over to play cards and Clue, jokingly started casting the Margaret Fuller Story. The big budget version would star either Jodie Foster or Lili Taylor—Taylor might also be induced to appear in the independent feature. Johnny Depp would obviously be ideal for Count Ossoli; understandably, one faction insisted on Gary Oldman. Opinion was also divided as to whether Lyle Lovett would make a more convincing Thoreau or Emerson. For the young Emerson, there was a comic yet oddly heated debate on the virtues of Joaquim Phoenix vs. a cravat clad Winona Ryder. For the made-for-tv-movie, they couldn’t think of any youthful equivalents of staples such as Lindsay Wagner, Meredith Baxter Birney or Tom Skerrit ( a plausible father in all 3 versions, they concurred).

The story would open in England, on the night before Margaret and Ossoli’s fateful sailing, with gracious Elizabeth Barrett Browning (Patti Smith?) hosting a gala farewell party: establishing the couple’s significance while affording juicy cameos, like Heather Locklear (or Patty Hearst) as George Sand. They debated having Keats and the Shelleys present, mostly to weave a Frankenstein subplot into the film—Cristina Ricci would make a wonderful Mary Shelley, and James Brolin a divine Frankenstein!—figuring nobody would recognize or care about a small anachronism. But in case any critics were unable to assent to this patently pomo aesthetic, they had fictionalized a certain Kelley and Sheats, possibly to be played by identical twins; John thought both might be power- fully portrayed by Courtney Love.

The very next morning, P B-R began composing this telling tale:

I passed the summer of 1816 in the environs of Geneva. The season was cold and rainy, and in the evenings we crowded around a blazing wood fire, which cackled like a howling ode. Occasionally we amused ourselves with some German stories of ghosts, which happened to fall into our hands. These tales excited in us a playful desire for imitation. Two other friends (a tale from the pen of one of whom would be far more acceptable to the public than any thing I can ever hope to produce) and myself agreed to write a story, founded on some supernatural occurrence.

The weather, however, grew serene; and my two friends left me to take a journey among the Alps, and lost, in the magnificent scenes which they later present, were all their ghostly visions. The following tale is the only one completed:

I awoke one morning, and began my usual ablutions, when I was quickly overcome by an attack not of dizziness exactly, rather eerieness. My familiar pink tiled bathroom felt alien, slightly malevolent. I couldn’t remember if I was at home or somewhere on the road, in the midst of travels. Then, I saw her standing there, the ghost of my recently deceased soul-mate, Kathy Acker: vibrant, sunny, knowing, brilliant, looking like no ghost of which I could conceive.

Kathy beckoned me to follow. Without even brushing my teeth, I left the house, or passed through its pulsating portals. Outside, we were on a concrete patio which had many broken old tv sets scattered around its perimeters, weeds growing haphazardly in the cracks. With a wave of relief, I realized that we were in the pleasantly run-down seaside shack where I had resided in my student years; Kathy was also a graduate student, living nearby with her younger, composer lover and several cats. The blue blue sky was broad and dotted with glorious, puffy white clouds, which seemed dense but like they might precipitously vanish. Down the hill, the shining sea called. We were so happy to be alive, and together.

The noise of Spanish dance music trumpeted seductively. Peering behind the house, where formerly a small vegetable and marijuana garden had provided us with mucho nourishment, I found a makeshift wooden structure—imagining it a captivating cabana in a small Mexi- can seaside resort. I thought about the Sea of Cortex, for some reason. We noticed that drinks and sandwiches were being served, so we entered the haunted refreshment area.

A number of disconsolate individuals sat stiffly at separate tables; a few obvious expatriates, and quasi-Eurotrash tourists, were reading thin volumes of rhymed verse. Kathy raised a dubious eyebrow, murmuring that the tattered appearance of this place should really have drawn a more buoyant and funky crowd. We were getting ready to make our way down to the beach, when a distraught yet lithe man rushed into the enclosure, breathing heavily, “le migra,” trying to blend into the woodwork.

Suddenly, several inert patrons unexpectedly sprung into action. Motioning for the recent bearded arrival to join them, one sedate Eng- lishwoman handed him old-fashioned writing implements and a spanking new Baedecker’s. They hurriedly dressed the refugee in an inexpensive fedora, and cheap but trendy paisley, suggesting that if the police arrive, he speak only Russian. Surprisingly, he responded fluently in what sounded like the mother tongue all right, shyly smiling his thanks. People at other tables nodded their approval; some began to spoon.

Kathy and I sat back down at a table speckled in sunlight, and ordered cassis, though I didn’t quite know what that meant. We grumbled about how awful grad school was, despite our studying dyspeptic and witty old Jonathan Swift. Then we laughed again about the grotesque reading we had recently attended in New York, in which the bourgeois essayist Philip L. prattled on about his newly renovated loft in Soho, and a très naughty dog who simply refused to stop peeing on the darling wooden floors.

The migra never appeared. As the afternoon shadows lengthened, more and more immigrants wandered in, their tattered rucksacks bearing precious photographs: perhaps a cameo or old-fashioned piece of jewelry, maybe a bit of provolone or passion fish. Weary and suspicious, nonetheless most seemed immensely relieved to have arrived at this charming canteen. Ostentatiously sighing, they took seats, ordered ceviche and Dos Equis. The music and chatting grew louder yet more languorous.

These sweet and shell-shocked souls became almost merry. Oddly, a number of them somehow knew Esperanto; many also spoke Spanish and some English. Photos of loved ones accompanied funny, fortunately not-too-lengthy anecdotes told around the heartily decorous outdoor fireplace. Dancing commenced. Our original refugee was now back in faded cut-offs and sandals, standing by the fence, staring wistfully out to sea. He began to jump up and down to the captivating samba music.

At first, flailing in futile escape gestures, he could only move in place, frantically kicking his heels higher and higher. After awhile, partly because nobody visibly reacted, this lovely man’s motions became increasingly rhythmic, his expression concentrated and joyful, released. His droopy eyes were simultaneously more lucid and narcotic; sometimes, he reminded me of himself! His laugh was that of a beaming boy turning green. Kathy and I suddenly knew that we were sharing a wonderfully improbable moment: there in this sprawling seaside cabana in a town so plainly doomed to horrific gentrification, solace in communion was temporarily granted us all.

Weeks later, my dear comrades returned from their mountain trek, and I read them my tale. When the name “Kathy Acker” was first uttered, Kelley and Sheats started, as if harkening to a distant star; shortly, both poets were weeping. Sheats sadly opined: death comes far too early to genuine artists, the very people vitally needed to grow old, and truly be identified as the public’s seers and healers. Instantly, we all had a foreboding of never reaching the age at which it would become necessary to practice steely indifference. A collective shiver was followed by lissome Sheats quickly adding, not without a soupçon of slyness, “Still, we are already immortal—and we know it.”

So we rushed down to the sea, to feel a tiny toehold on eternity. The rain had stopped: egrets were cutting capers in the moonlight; sudsy surf shimmering. Lucid and lovely. But Kelley (and perhaps Sheats) abruptly caught sight of the doomed ship Elizabeth, tilted upright in the sand bar; anguished Margaret Fuller clutching her baby, seemed to sight them too—distant onlookers, safely ashore. I also had a momentary, stark glimpse of the ghostly Elizabeth, pounded by waves of death. Instinctively, I tried to forget, and stay grounded: pondering the preparation of pungent leek soup, for the coming midnight repast. Little did I realize how impossible that simple task would soon prove to be.

4.

THE ETERNAL TRIANGLE, Or Love is a Square

Margaret Fuller witnessed the marriage of the two people she was most in love with: Anna Barker and Sam Ward. It was Margaret’s fervent conviction that they were both all which she herself was not: gracious, handsome, wealthy, plus possessing none of her ungainly, and implacable ambitions. Anna Barker was a fresh, exquisitely captivating spirit. Upon first meeting her, Emerson wrote, “She had not talents or affections or accomplishments or single features of conspicuous beauty, but was a unit and whole, so that whatsoever she did became her...She had an instinctive elegance...No princess could surpass her clear and erect demeanor...Her conversation is the frankest I ever heard. She can afford to be sincere. The wind is not purer than she is.” Whenever Margaret was inclined toward playing Madame de Staël, Anna was forever her rapturous Madame Recamier.

Seven years younger (in other words, exactly the right age for her), Sam Ward was a passionate devotee of fine arts, about which Margaret knew very little until the pair literally pored over thousands of prints and sketches that Sam had brought back from his two-year grand tour of Europe: a reward for graduating from Harvard College, of which, in addition to the Boston Athaneum, his father was treasurer. Margaret first met Sam the year before, on a party which journeyed by steamboat to the upper Hudson with its spectacularly scenic gorges and deep ravines. Some twelve miles north of Utica, Margaret and Sam took a long walk at Trenton Falls, where they came upon a clump of snowdrops at the foot of a rock. “It passed quick,” Margaret wrote to Emerson, “as such beautiful moments do, and we never had such another.”

That union of two adored ones, Sam and Anna, was engineered by the same surrogate mother who initiated Margaret into the elite, intellectual circles she so craved, who arranged the steamboat journey where she met Sam, and who later introduced him to Anna. Eliza Farrar and her husband accompanied Sam on his European tour, where Eliza’s cousin Anna joined them. More than anything, Margaret had wished to go to Europe. She was planning on it, until her father’s death threw his family into a state of genteel poverty. Instead, she went to work, while the beloved rich and beautiful ones traveled in style, falling in love under Eliza’s glowing sanctions.

Soon after returning, Sam announced his engagement. But Anna broke it off until Sam agreed to give up a potential career in fine arts to go into his father’s bank—hopefully, Margaret derived some satisfaction from that ultimatum. Sam and Anna’s liaison prompted many “vows of renunciation”: a chief component of Margaret’s “quasi-erotic intensity of friendships with both sexes.” The belief that she was “not yet purified” led Margaret to think of Vestal Virgins, and she wrote, “Let the lonely Vestal watch the fire till it draws itself and consumes this mortal part.”

The message Margaret mirrored from all quarters was ancient, deeply familiar: don’t even consider trying to be both a woman of letters and a woman. You are unsexed. Sacrifice desire. This life of the flesh is not yours; it is our life. As the American oratario drew to a close, Margaret ripped off her own pantaloons, positively insisting that someone else dutifully wipe up the tear-stained chiffonier. Blood of our blood, we rise again to live.

Mel Freilicher retired from some four decades of teaching in UCSD's Lit. Dept./writing program. He was publisher and co-editor of Crawl Out Your Window magazine (1974-89), a journal of the experimental literature and visual arts of the San Diego/Tijuana region. He's been writing for quite some time. He is the author of The Unmaking of Americans: 7 Lives, Encyclopedia of Rebels, American Cream, and Privilege and Passion: The Novel (forthcoming) all on San Diego City Works Press.