by Mel Freilicher

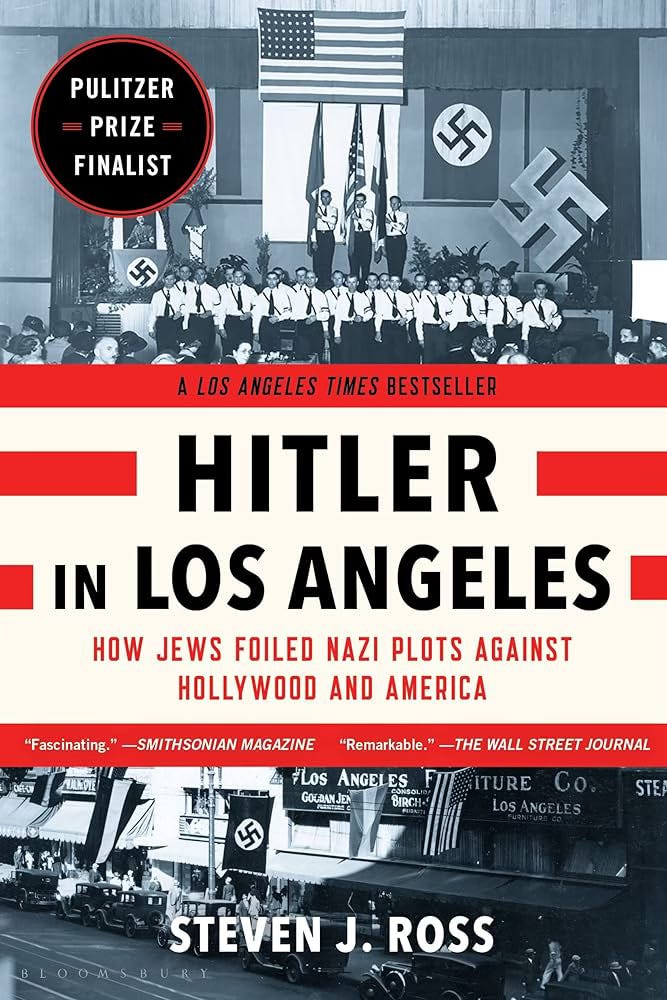

Hitler in Los Angeles: How Jews Foiled Nazi Plots Against Hollywood and America by Stephen J. Ross on Bloomsbury, 2017

On a cloudy Sunday morning in late September, 1935, tens of thousands of Los Angeles Times subscribers opened their papers to discover an anti-Semitic flyer had been inserted. Issued by the American Nationalist Party, with close ties to Nazis and the Ku Klux Klan, and written in the style of the Declaration of Independence, its preamble called for a boycott of all things Jewish in the United States, particularly the perfidious movie industry.

A list of grievances stated, “Through their closely unified banking interests…they have constituted themselves a menace to our free institutions, our Christian civilization and our Aryan culture.” The timing was not coincidental: coming two weeks after the German government had issued the Nuremberg Laws making it difficult for Jews to obtain citizenship and prohibiting intermarriage or sexual relations with Germans.

As the week progressed, these proclamations littered the streets of San Francisco; left on the lawns and slipped under the doors of Jewish shops in San Diego, Santa Barbara, Beverly Hills, Hollywood, and Boyle Heights, the eastside L.A. community of Jewish leftists. From Fresno to Modesto, the San Joaquin Valley was plastered with them. In Portland, the Friends of the New Germany disseminated bundles; by December, more than 40,000 copies of the flyer were circulating in as many as seventeen cities from Pasadena to Chicago.

Southern California had a long history of anti-Semitism and right-wing extremism. However, 60-65% of respondents in national opinion polls conducted in 1938 by both Fortune magazine and the American Jewish Committee felt “Jews had too much power” in America. Even in a wartime poll, Jews were ranked as the “racial or religious group” posing the greatest threat to American society, when respondents were asked to choose among them, Germans, Japanese, Negroes, and Catholics.

Between 1933 and 1941, 200,000 refugees fled from Germany and Austria to the United States (of course, ports were closed to a much greater number); 10,000--half of them Jews—settled in L.A. The Jewish population increased rapidly, from 2,500 in 1900 to 70,000 on the eve of World War II. By 1929, Boyle Heights was home to 10,000 Jewish households, nine hotels, two theaters, a variety of cultural institutions and many inexpensive homes and apartments.

“It is hardly surprising that Hollywood activists were at the forefront of internationalist politics when most Americans were still isolationists,” Stephen Ross points out in his very cogent, readable and detailed study. A national poll in November, 1936 revealed 95% opposed U.S. participation in any potential European conflict.

A Professor of History at USC, Ross came to this subject matter late in his career, even though or because, he states, his parents were Holocaust survivors. Clearly an experienced and thoughtful writer, he does a fine job of laying out a complex picture in a kind of real-life thriller.

The hero of his story is Leon Lewis, a Jewish lawyer who’d been operating a successful spy ring, since August, 1933, infiltrating fascist organizations in L.A. to report on their activities, expose Nazi-led public events as such, and inculcate dissension among the leaders (COINTELPRO, move over!). By the 1935 LA Times incident, Lewis’ spies had already seen many instances of money and Nazi propaganda being illegally smuggled into L.A. ports, much less closely monitored than New York’s.

In March 1933, a former German captain and his Nazi cohorts set up quarters at the Alt Heidelberg, opening the Aryan Bookstore in a multipurpose building that was “a lively haunt of the city’s German community,” also containing a beer garden, a large German restaurant, several private dining rooms, Friends of the New Germany (FNG) headquarters, a big meeting hall, often packed when Bund leaders came to town (one “delivered a fierce attack on Scholastic magazine for its communistic efforts ‘to discredit Nazism and Fascism in the eyes of the school children’”). In basement barracks, unemployed Germans were fed, housed, and indoctrinated.

Holding closed weekly meetings, L.A. Nazis were attracting dozens of sympathizers: efforts to recruit active agents aimed chiefly at disgruntled German American veterans. So Leon Lewis did exactly the same! His extensive spy ring was comprised almost entirely of German-American vets, and often their wives, posing as disillusioned emigres, mostly recruited from the American Legion (the downtown post was atypically liberal), and Disabled Veterans of America. Only one of Lewis’ agents was Jewish.

Nazis had every reason to believe their recruitment strategy would succeed. In May 1932, 10,000 World War I veterans, many of them unemployed since the onset of the Depression, marched to Washington, D.C. to demand an early payment of their military service bonus. When Congress refused, they camped out near the Capitol in peaceful protest. Three months later, President Hoover ordered General Douglas MacArthur to disband the camp: an armed force of 400 infantry, 200 cavalry, and 6 tanks gassed the veterans and burned their makeshift tent camp to the ground.

The election of FDR did little to quell growing discontent among veterans. Shortly after taking office, Roosevelt tried to balance his budget by slashing pensions for 20,000 veterans by 40%, and reducing monthly disability stipends. Faced with outrage from veterans groups, and the threat of a second march, Congress restored many of the cuts. But in another series of reductions, disabled veterans who’d been supporting their families on $60 to $80 a month were permanently cut off from all benefits.

Lewis saw how many Angelenos were attracted to flamboyant demagogues such as Gerald B. Winrod, the far-right Kansas evangelist known as the Jayhawk Nazi, later shown to be in the service of the Reich Ministry of Propaganda. Father Charles Coughlin’s weekly anti-Semitic rants reached 14 million radio listeners. William Dudley Pelley led the nation’s largest and most dangerous fascist organization, the North Carolina-based Silver Legion of America (known as Silver Shirts). Members donned uniforms much like the ones Brownshirts wore: sewed themselves so as not to wear anything touched by Jews.

In his early years, Pelley was a successful journalist, fiction writer (winning the O. Henry award in 1930) and screenwriter--between 1927 and ’29, Hollywood produced sixteen of his films. In 1928, while living in an L.A. suburb, he underwent a life-changing experience. Awakened between 3 and 4 in the morning by an inner voice, shrieking, “I’m dying! I’m dying!” he experienced a physical sensation akin to a “combination of heart attack and apoplexy.”

Recounting how he then plunged “down a mystic depth of cool blue space,” Pelley found himself on a naked marble slab, surrounded by two “Spiritual Mentors,” who ostensibly guided his earthly activities from then on, urging Pelley to build the Silver Legion into a formidable quasi-religious, quasi-paramilitary organization. Christ had asked him to transform America’s spiritual character.

Pelley set out to rid the nation of its two greatest dangers: Jews and communists. Dividing the United States into 9 regions, he ordered each post to organize a paramilitary band of a hundred, dues-paying “actionists,” presided over by a commanding officer who answered to him. Long before Hitler’s final solution, Pelley’s 1933 book promised a “permanent solution to the Jewish problem,” involving mandatory ghettoization.

Los Angeles Jews were also threatened by armed anti-Semitic groups in Mexico. Shortly after Hitler’s rise to power, Nazi emissaries traveled to Mexicali to help General Nicolas Rodriguez organize the Gold Shirts, with the goal of a fascist takeover of the government. In March, 1935 the former general marched his Gold Shirts to the president’s palace in Mexico City. During an ensuing riot, 5 of them were killed, 70 people wounded. Rodriguez was stabbed, taken to a hospital then exiled to Texas. He often visited Deutsche Haus to speak, and plot with Silver Shirts for his return to Mexico.

In the ‘30s, the German American Bund placed a number of agents, skilled mechanics, inside Douglas and other aircraft and munitions factories, with the plan of paralyzing Pacific coast defenses by blowing them up along with docks and power plants.

To say the least, the growing fascist movement in this country was not closely monitored by government agencies, either regional or federal: J. Edgar Hoover was way more obsessed with the Red menace. (During the early 1920s, his agents filed over 1,900 pages of reports on Charlie Chaplin alone.) So the question of who Lewis and his allies could trust with information was of paramount concern until the U.S. entered the war in 1942.

Quite a few high-level L.A. politicians and law enforcement personnel were Nazi sympathizers. William “Red” Hynes, LAPD police captain and head of its notorious Red Squad, was a known anti-Semite, and a regular at Friends of New Germany headquarters. Back in 1922, the L.A. district attorney had raided Ku Klux Klan headquarters, and found a local membership list of 1500, including the L.A. County sheriff, and chief of police.

Initially, Leon Lewis turned to police chief, James “Two Gun” Davis, but quickly discovered the man admired Hitler, and would supply no police data. Rumors of Davis joining the Silver Shirts persisted. One of its members told Lewis’ agent, the “entire Los Angeles Police Department, Sheriff’s Office, Federal Office, including the Department of Justice had all taken the oath of the Silver Legion.”

Laura Rosenzweig’s Introduction to her Hollywood Spies notes how widespread political espionage was in L.A. in the ‘30s, by the police as well as by both right and leftist groups. Ultraconservative, The Better American Foundation paid members of right-wing organizations like the Silver Shirts to infiltrate and disrupt Communist Party meetings.

Compensating high school students who reported on “subversive activities among students and teachers,” according to writer Carey McWilliams, for 20 years, the BAF also hired a “prominent Los Angeles clubwoman” to sit on the boards of liberal organizations and report on their activities.

According to three informants, Rosenzweig writes, the Friends of New Germany’s plan was to incite unrest among American workers to hasten a communist insurrection. Then the private militia they were training would come to the rescue, “consolidating and marching in military phalanxes to take over the government…shoulder-to-shoulder with U.S. veterans,” starting in cities where the FNG was most active--St. Louis, Chicago, New York, and L.A. Within two weeks, Protestant churches, led by the Lutheran Church, would launch a boycott of Jewish businesses.

On New Year’s Eve of 1936, Lewis received a report on the American National Party, an alliance of various anti-Semitic groups, the KKK, Silver Shirts, and Russian National Revolutionary Party. Its inner circle included highly reputable figures such as former Los Angeles mayor and Klan leader, John Porter, a California state senator, the Pasadena city prosecutor, and a Pasadena real estate agent who later served in Congress.

The ANP planned to kidnap and hang Leon Lewis and 20 nationally prominent Angelenos. Their original hit list—a second appeared the following year—included local attorneys and judges, and film director and choreographer Busby Berkeley. (An ANP leader quipped, “Busby Berkeley will look good dangling on a rope’s end.”) To send a stark warning to Christians too sympathetic to Jews, the list also included a district attorney and political leaders.

Plans entailed bombing all the victims’ homes, and killing everyone in them in one day, while also establishing assassins’ escape routes and alibis. Its mastermind, Leopold McLaglan, was an “intelligent, dangerous, and delusional” British combat veteran and martial arts expert who knew how to kill and taught others to do so with precision.

McLaglan, brother of the famous actor, Victor McLaglan, recipient of a best Oscar performance in The Informer, had fought in the Boer War and World War I, then taught ju-jitsu and martial arts around the world, including at Scotland Yard.

His list included Lewis, naturally, along with some of the most famous people in the world: among them, Jack Benny, Herbert Biberman, James Cagney, Eddie Cantor, Charlie Chaplin, Sam Goldwyn, Al Jolson, Frederic March, Louis B. Mayer, Paul Muni, B.P. Schulberg, Donald Ogden Stuart, Walter Winchell, William Wyler, and two women—actresses Sylvia Sydney, and Gloria Stuart.

McLaglan boasted, “I can get the Nazi boys and the White Russians who would do this for us,” while procuring all the dynamite he needed “through the police.” When Lewis’ agents exposed the plot, McLaglan was sentenced to five years in prison. Instead, he was allowed to bail on the next boat back to Britain.

Hatred of fascism led Hollywood liberals, Communists, and some conservatives to join a wide range of Popular Front groups such as the Motion Picture Artists Committee to Aid Republican Spain (with 15,000 members at its peak), the Joint Anti-Fascist Refugee Committee, and most notably, the Hollywood Anti-Nazi League (HANL), an offshoot of the New York Non-Sectarian Anti-Nazi League, founded in 1933 by Samuel Untermeyer, the attorney largely responsible for leading a boycott against importing German goods.

Perceiving the neophyte HANL as “babes in the woods,” Leon Lewis agreed to serve as liaison, providing a steady stream of information and cogent analyses. HANL was led by screenwriter Donald Ogden Stewart: author of sophisticated comedies like Philadelphia Story, a member of the Algonquin Round Table literary circle, friends with Dorothy Parker, Robert Benchley, George S. Kaufman and Ernest Hemingway.

At one HANL meeting, Stewart stated he had been a member of the Communist Party. Subsequently blacklisted in 1950, he and his wife, the journalist and activist, Ella Winter (formerly married to muckraker Lincoln Steffens), emigrated to England where he lived the rest of his life.

The Hollywood Anti-Nazi League included an amalgam of liberals such as Melvyn Douglas, Edward G. Robinson, Sylvia Sidney, Eddie Cantor and Gloria Stuart, along with prominent conservatives such as John Ford, Joan Bennett, and Dick Powell. Renting space on Hollywood Boulevard between Grauman’s Chinese Theater and Musso & Franks, the popular bar frequented by screenwriters, HANL proceeded to mount star-studded anti-Nazi demonstrations, photographs of which appeared on front pages of the nation’s newspapers.

A huge rally at the Shrine auditorium of over 7500 people, with another several thousand outside, included a large contingent “of famous screen personalities.” HANL’s well-publicized events featured Viennese-born director Fritz Lang, black scholar and activist W.E.B. DuBois, actors Ray Bolger, Fanny Brice, Bing Crosby, Frederic March, Joan Crawford, Fred MacMurray, and Sophie Tucker. The League drew nationwide attention by boycotting Hollywood visits of Benito Mussolini’s son, and of Hitler’s favorite filmmaker, Leni Riefenstahl.

Viewing HANL as a serious threat, Nazi operatives met frequently to discuss the best ways of disrupting their rallies. One outrageous suggestion entailed filling an auditorium with cyanide fumes then firing “automatic rifles and sawed off shotguns” into the audience. They discarded the idea of making a hypodermic gun inside a fountain pen that could shoot poisoned needles at Jews, as well as the suggestion of sending a gang of thugs to provoke a fight.

Every day Lewis ran the risk of being attacked by some crazed fascist. Nazis and Silver Shirts were quite aware he was running a spy service out of his office in the Roosevelt Building, just minutes from Deutsches Haus. Clearly courageous, skillful in recruiting and training fellow vets, Leon Lewis appears to have been a truly remarkable figure, and a modest one—he left no diaries or accounts of his life, only correspondence with spies and colleagues. “Few people talk about him in their memoirs, and there is little trace of his personal life in newspapers,” Ross notes.

Born in 1888, Leon Lewis attended Milwaukee public schools, went to the University of Wisconsin and George Washington University, earning a law degree from the University of Chicago. He became the first executive secretary of the Anti-Defamation League, created in 1913 after an Atlanta jury wrongfully convicted B’nai B’rith president Leo Frank of murdering a thirteen year-old girl who worked in the pencil factory where he was superintendent. (Frank was sentenced to death; the Supreme Court refused to hear his case. Two years later, when the governor of Georgia commuted his sentence to life imprisonment, infamously, Leo Frank was lynched.)

Described by Ross as a lawyer with a social worker’s heart, Lewis spent the next few years speaking extensively throughout the Midwest, documenting instances of discrimination and aiding vulnerable Jews. In 1917, two months after the U.S. entered World War1, Lewis enlisted in the army and was sent to France. During 18 months of military service, including combat in the Somme, he rose from private to captain.

At war’s end, recently promoted Major Lewis served as Deputy Chief of the Army’s War Relief Section, organizing Red Cross aid for wounded American soldiers in Great Britain. Returning to Chicago in 1919, he married, resumed his position with the ADL, and began presenting reports to the Central Conference of American Rabbis on the dramatic rise of anti-Semitism in Europe and the U.S.

Becoming executive secretary of ADL’s new international division, he also served as founding editor of the B’nai B’rith Magazine, and helped organize the Hillel Foundation to further Jewish life on college campuses. When ADL moved its national organization to Cincinnati, Lewis went to work in a private law firm before relocating to Los Angeles, setting up a practice specializing in business affairs. As ADL’s representative to Hollywood, he monitored films for anti-Semitic images.

Both Ross and Rosenzweig intensively cover the March 13, 1934 meeting at the Hillcrest Country Club where Leon Lewis made the case for funding to the wealthiest Jews in the city who he’d tried approaching before, but had lacked the right connections. However, the Nazi faction of the Friends of New Germany had recently taken over the German-American Alliance, the affluent umbrella organization for the city’s German voluntary associations.

The Nazis won the highly publicized trial to overturn those internal elections. Several of Lewis’ agents were exposed, but now Nazi presence in L.A. was unequivocally visible: enabling Lewis to broker the Hillcrest Country Club meeting through Hollywood attorney, Mendel Silverberg, an acquaintance from veteran circles.

Born in L.A. to assimilated Russian and Austrian Jewish parents, and raised as a Christian Scientist, Silverberg was a major power broker in the Republican Party. (Louis B. Mayer was the state chairman of the Party in 1932 and ’33.) The nation’s most powerful entertainment attorney, Silverberg represented MGM, RKO, and Columbia studios, along with individuals like Jean Harlow, and Louis B. Mayer.

Mayer, Irving Thalberg, producer David O. Selznick, directors Ernst Lubitsch and George Cukor among others were present from MGM. Five other studios were represented by chief executives, producers, directors, and legal counsel. Silverberg was able to galvanize representatives from the “Old Money” downtown professional Jewish establishment as well.

Lewis was prepared. As the men emerged from the club’s large private dining room and took their seats, each found several copies of Silver Shirts periodicals, Liberation and Silver Ranger, containing a stream of vicious articles denouncing the Jewish-dominated movie industry which would “rip our Divine Constitution to shreds and hand it over, HEADS BENT LOW, SPIRITS CRUSHED, MORALE DESTROYED, TO THE BULBOUS NOSED LORDS OF INTERNATIONAL JEWRY.” That night, Lewis secured $24,000 (approximately $425,000 in 2015 dollars) in pledges, and the Los Angeles Jewish Community Committee was formed with some 30 members.

Almost always with 100% attendance, LAJCC weekly meetings deliberated how to respond to informants about escalating Nazi activity in the city. The Committee required Lewis to report on Nazi activity within their studios, while Lewis, in turn, insisted: “We must keep Jewish participation and cooperation in the background as these veterans are not doing this work because they love the Jew, but because they have been impressed with the seditious and Fascistic character of the propaganda”--rather than with its anti-Semitism.

While studio heads paid close attention to their above-the-line personnel—an industry term for the stars, writers, directors and producers—they knew far less about the craftspeople who comprised 80 to 90% of their employees. After interviewing every Jew who’d worked as an extra over the past several years, Lewis discovered widespread discrimination by studio foremen, many of whom were openly sympathetic to the Silver Shirts.

Paramount’s two studio managers had fired so many Jewish employees in the past few months, “the number of Jews can be counted on the fingers of one hand.” One manager was eventually canned “because he attempted to adopt Hitlerism, as a policy in running the studio.” Paramount was not unique, Lewis warned—other studios had also “reached a condition of almost 100% [Aryan] purity.” We don’t learn if Lewis’ report changed anything.

Neither Leon Lewis nor any members of his courageous squad is noted as being particularly ideologically left, though naturally there were plenty of Reds in Hollywood. The LAJCC made sure to distance itself from Jewish leftists of Boyle Heights, so they themselves would appear more “American.”

Initially, Mayer asked his friend William Randolph Hearst to have a chat with Hitler, and “was relieved when Hearst assured him that Hitler’s motives were pure.” Neil Gabler further reports in An Empire of Their Own, Irving Thalberg (Mayer’s ”Boy Wonder” production chief, considered the creative head of the studio), returning from Germany in 1934,“sanguinely pronounced that ‘a lot of Jews will lose their lives’ but ’Hitler will pass, the Jews will still be there.” Thalberg insisted, “German Jews should not fight back, and Jews throughout the world shouldn’t interfere.”

Some Hollywood studios closed down their relations with Germany in 1936, but M.G.M. and two other studios continued, avoiding using Jewish stars. Broadway Melody of 1938 ran for months in Berlin to standing room only crowds and wild applause. “Hitler loved Garbo and Jeanette MacDonald and ran their pictures over and over again,” Charles Higham writes in Merchant of Dreams: Louis B. Mayer, M.G.M. and the Secret Hollywood. Hitler’s love for the racist Gone with the Wind was legendary; finally, jealous of his mistress’, Eva Braun’s, infatuation with Clark Gable, that movie was banned.

Both Ross and Rosenzweig supply many examples of what scant interest the communist-obsessed government took in the Nazi fifth column. Clearly, American Jews, confronted with direct threats to their own well-being, needed to organize to defend themselves. And who had more money than Hollywood’s moguls? (For 7 years running, Mayer’s salary was the highest in the country; he also had extensive real estate holdings.)

But defending your own community isn’t exactly ideological commitment to humanity, or to solidarity with society’s multitudinous fucked-over “Others.”

Louis B. Mayer was a poor Ukrainian immigrant: the only thing he had in common with many of the radicals I’ve been writing about for years. Never having made any money, Mayer’s father moved the family to New Brunswick, Canada when Louis was a child. The provocative and controversial thesis of Neil Gabler’s Empire of Their Own concerns, of course, over-compensation: the Jewish men chiefly responsible for establishing Hollywood, immigrants or children of immigrants who had all “grown up in destitution…with a patrimony of failure.”

Gabler writes, “One hesitates getting too Oedipal here,”—though, in fact, he doesn’t seem at all hesitant--”but the evidence certainly supports the view that the sons…launched a war against their own pasts.”

Certainly, Mayer is portrayed as highly ambitious and strategic from an early age. Involved in the nickelodeon business from its start, his first major financial success involved maneuvering to be sole New England distributor of D.W. Griffith’s racist epic, Birth of a Nation—later, it was alleged Mayer “fiddled the books,” as his biographer, Charles Higham, puts it.

Declaring his own birthday to be the 4th of July (in what Higham loyally if fatuously describes as Mayer’s “patriotic whimsicality”), he gave the entire studio the day off to celebrate it along with the nation’s birth. “Profoundly sentimental,” his favorite painter was Grandma Moses; his favorite composers Rachmaninoff and Tchaikovsky.

Even Higham, a most ardent admirer—“Mayer was in fact an inspired and culturally aware executive who made the most beautifully crafted of Hollywood movies”—admits the mogul “could be manipulative, despotic, cruel, unforgiving.”

]“Actors did not know what was good for themselves; he controlled them to the point of personally putting saccharine in their coffee…telling them what they could eat for breakfast, lunch and dinner, whom they could marry, whether it was time to have a baby or not, how to obtain an abortionist if a picture was at stake.” Mayer actually addressed them as his children, allegedly making “everyone who worked for him feel they were members of a royal family.” (Married twice, Mayer had 2 daughters.)

In love with many famous women, according to Higham, Mayer “conducted his affairs with all the courtly gallantry of one of his WASP movie heroes, with flowers, champagne, mothers brought along as chaperones, discreet rhumbas and tangos in nightclubs protected from the press.”

In his biography of Judy Garland, Get Happy, Gerald Clarke depicts Mayer as “one of the worst sexual predators” at the studio (having even “pawed and propositioned” Shirley Temple’s mother). “Between the ages of 16 and 20, Judy herself was to be approached for sex—and approached again and again,” especially by Mayer. “Whenever he complimented her on her voice—she sang from the heart, he said—he’d invariably place his left hand on her beast to show just where the heart was.”

When Judy finally had the courage to put a stop to it (“If you want to show where I sing from—just point!”), to her surprise, Mayer burst into tears, crying, “How can you say that to me, to me who loves you?” She ended up consoling him. Years later, she wrote, “It’s amazing how these big men, who had been around so many sophisticated women all their lives, could act like idiots.”

Although Mayer’s tastes were for sentimental, patriotic, wholesome entertainment, Higham reveals fascinating details about some of the studio’s great films. Howard Hughes, allegedly having an affair with Katherine Hepburn at the time, held the rights to the play, Philadelphia Story. Both agreed not to sell it to Mayer unless she played the lead (as she had in the theater), though she was then considered “box office poison.” ”Despite Mayer’s continuing dislike and contempt for him as a homosexual,” Hepburn insisted George Cukor direct the film, and pro-communist Donald Ogden Stewart adapt the screenplay.

Mayer did have the good sense to hire Irving Thalberg as his chief producer who “emphasized good taste meticulous period detail in historical films and the classical dramaturgy of struggle.” Well educated, a total perfectionist and workaholic, Thalberg had rheumatic fever as a youngster; until his death at age 37, his health was always precarious. “He was not to be crossed,” Higham comments, “he had a fiery temper, surprising in one so frail and so complete a certainty in his own judgment that he would strike fear.”

Thalberg’s politics were no better than Mayer’s, though as a young man Irving had been a Socialist. Hollywood contributions to anti-Nazi activity slowed down, Stephen Ross points out, the fall that industry leaders from both parties turned their attention and money to defeating Upton Sinclair’s gubernatorial campaign.

The longtime socialist had stunned the political establishment by capturing the Democratic nomination for governor of California in August, 1934 (having previously run unsuccessfully for Congress several times on the Socialist Party ticket). Sinclair’s EPIC platform (END POVERTY IN CALIFORNIA) called for a graduated income tax which would increase to a point where all incomes over $50,000 would be taxed at 50%.

Sinclair also promised to initiate a special tax on the state’s highly profitable movie industry. As Billy Wilder, recently arrived from Austria, noted, Sinclair “scared the hell out of the community. They all thought him to be a most dangerous Bolshevik beast,” and teamed up with Hearst and others to trounce him.

When polls showed Sinclair and his Republican rival running neck and neck, Mayer and Thalberg produced a series of three fake newsreels, California Election News, distributed free to California theaters: well-dressed, nice looking people spoke favorably of the Republican candidate, and criminal looking types with Russian accents expressed their hopes for Sinclair’s victory.

“Vy am I foting for Seenclair?” boasted a bedraggled, wild-eyed immigrant. “Vell, his system vorked vell in Russia, vy can’t it vork here?” In another newsreel, an army of hoboes descend on California in anticipation of Sinclair’s election.

When actor and Democratic activist Frederic March blasted MGM’s scurrilous newsreels as “the damndest unfair thing I’ve ever heard of,” Thalberg quickly shot back, “Nothing is unfair in politics. We could sit down here and figure dirty things out all night and every one of them would be all right in a political campaign.” Only a handful of movie people opposed the studios, organizing a writers’ committee for Sinclair.

At MGM, “simple extortion was thought to be the most efficient way to raise vast sums for the defeat of Sinclair,” Leon Harris writes in UPTON SINCLAIR: American Rebel. At first every employee earning over one hundred dollars a week was expected to contribute a day’s pay. Soon not only highly paid employees but also stenographers, technicians, writers and others were tapped. Harris quotes an anonymous, indignant scenario writer: “Few studios were not involved in the drive…Many employees were given blank checks made out to Louis B. Mayer.”

Studio heads threatened to move the industry to Florida if Sinclair was elected. “That’s the biggest ‘piece of bunk’ in this entire election,” Upton told delighted audiences. “They couldn’t move if they wanted to. It would cost them too much...Besides, think of what those big Florida mosquitoes would do to some of our film sirens. Why, one bite on the nose could bring a $50,000 production loss.”

Mayer’s reactions to the visits of Vittorio Mussolini and Leni Riefenstahl were considerably less than admirable. The dictator’s son was invited to Hollywood by Hal Roach, a producer of Harold Lloyd, and particularly Laurel and Hardy films, who’d formed a company with Vittorio to make a series of five movies to be distributed by M.G.M.

At this time, “as has been noted, it was not uncommon for America business leaders, including the heads of studios, to express an unabashed admiration for Mussolini,” Higham writes. “Unlike Hitler, he was not taking a strong line on Jews; he was considered to be a bulwark against Communism.”

While a handful of pro-fascist Hollywood figures received Vittorio—including Walt Disney, Gary Cooper, Winfield Sheehan (a top executive at Fox studios, responsible for Shirley Temple’s career), the censor Will Hays and William Randolph Hearst—adverse reaction was abundant.

The Anti-Nazi League, led by Fredric March and James Cagney, held a meeting on the night of his arrival, stating every effort must be made to expel Mussolini. Popular Hollywood gossip columnist, Jimmie Fidler, denounced him, while anti-fascists in the Screen Actors’ Guild took a full-page ad in Variety, quoting Vittorio’s statements glorifying war.

Black political figures shouted against him in downtown LA meetings. Calls to boycott Hal Roach films were reinforced with publicity about the book Vittorio had written on his father’s bombing of Ethiopia. His father was also supplying Spanish fascist Franco with arms and money, and Vittorio’s brother was flying for Franco in Spain.

“Mayer’s position was intolerable,” proclaims the ever-sympathetic biographer Higham, because the Roach deal had already been signed. Finally, “forced to a decision,” Mayer canceled the deal just after Vittorio Mussolini left town. But in secret, Mayer continued meeting with Nazi consul general, Georg Gyssling, to discuss how certain pictures with an anti-German bias might be presented without offense to the Nazi government.

Returning to Italy, Vittorio published an article stating it was not surprising how many American movies carried Communist propaganda because “Hollywood is as full of Jews as Tel Aviv.” He charged Hollywood with supplying its Italian earnings to the Reds in Spain. As a result of this threat to revenues, an industry representative was sent to meet with Mussolini to “correct the misunderstanding.”

Largely here to publicize her movie of the 1936 Olympic Games staged in Berlin and designed as a glorification of Hitler, Leni Riefenstahl was shunned by all except hardcore pro-Nazis. Even Gary Cooper, recently a guest of Herman Goering’s industrialist brother, originally called Miss Riefenstahl to pick her up at her Beverly Hills Hotel, then rang again, saying he was sorry he had to cancel—he’d been transferred to Mexico for a picture.

Riefenstahl did meet with the Museum of Modern Art’s film curator, with Henry Ford in the company of the local German consul, and had friendly discussions with ice skating star Sonja Henje. Walt Disney gave her a three hour tour of his studios: later, lying “he didn’t know who Leni Riefenstahl was when he gave her the tour.”

Over lunch, Disney talked about the fact that his Snow White and her Olympiad were in competition for the Mussolini Prize in Venice. (The year before, Disney had visited Italy and was entertained by Mussolini in his private villa.) He’d love to run her picture, but, alas, his projectionist was in the union which might then boycott the theater chains.

When Riefenstahl announced she wanted to meet Louis B. Mayer, Higham describes him as pacing up and down, with the head of his foreign division, discussing whether they would invite her to the studio. “Vogel pointed out to Mayer that he was damned if he did and damned if he didn’t.” Jews would call him a traitor, but if he kept her out, “the Loew’s shareholders would say he was letting personal feelings interfere with their dividends.” Phoning Riefenstahl, Mayer told her, “He would like to be friendly…but that feeling was strong against Germans.”

Should she happen to walk onto a sound stage, he speculated, and an electrician accidentally on purpose dropped a lamp on her head and killed her, M.G.M. would be legally liable. He offered to visit her instead. “But, furious, she refused to see him.” Sycophant Higham concludes this vignette bizarrely (but not uncharacteristically), with the statement: “One can only assume that Mayer’s admiration of her genius overcame his misgivings about her politics.”

Although I’ve mostly skimmed Higham’s 487-page bio, he seems quite determined to valorize Mayer, unwilling to ascribe mercenary motives to him. (Money talks, nobody walks.) His book’s index lists the heroic Leon Lewis exactly zero times. About Upton Sinclair, Higham declares his “campaign publicist exaggerated their [Mayer & allies] prejudices and political slanting.”

One provocative anecdote in his Prologue informs us Mayer twice “covered up acts of manslaughter, one of them by Clark Gable the other by John Huston.” Later we learn, driving drunk, Gable “rounded a bend too sharply, and struck a pedestrian, killing her instantly.” Allegedly, his heavy drinking was “partly because of the fact that Joan Crawford had dumped him in favor of the handsome young Franchot Tone.”

Mayer then selected an executive in his office to take the rap for Gable, claiming he was at the wheel: guaranteeing him lifelong employment at MGM, and an income until death. By prearrangement with the district attorney, Mayer’s chum, the fall guy pled guilty to a manslaughter charge, and served a 12-month prison sentence. Gable went off to Palm Springs; his salary was cut a bit.

Meanwhile, back in San Diego…Count Ernst Erich von Bulow ran a spy ring from his hilltop home where he could “see every move made by the Navy, the Marines, the fleet and the air base. His was the most strategic location in Southern California,” according to one of Leon Lewis’ chief operatives who believed von Bulow “was the head of German espionage on the west coast.”

In addition, Commander Ellis Zacharias, director of the entire Pacific coast of the Office of Naval Intelligence, termed San Diego “the very hub of the wheel of Japanese espionage.”

An Austrian spy who had been sent to investigate defense preparedness on the west coast was welcomed by von Bulow “as one would greet a friend of long standing.” After receiving permission to see the navy destroyer base in San Diego harbor (that district’s chief of Naval Intelligence was von Bulow’s “very close friend”), the two men spent half an hour going through the yards taking photographs, then driving along the shoreline. Later, they were chauffeured to Balboa Park, the grounds of the California Exposition, where they spent the evening watching “a bevy of beautiful women who performed in the nude.”

Lewis’ agents revealed a San Diego post of the Silver Shirts regularly used “graphic pictures of a dead Christ being feasted on by Jewish communists to get a rise from the audience.” Ross also describes an occasion when agents discovered two marine corporals selling government rifles and 12,000 rounds of ammunition to the Silver Shirts. Not trusting either L.A. or San Diego police chiefs, Lewis alerted Naval Intelligence authorities who seized the weapons and dismantled storm trooper units, “well armed and trained in the use of their weapons.”

Another incident involves a six-foot-one “distinctly German looking Californian,” Chuck Slocombe, “the most unlikely of Lewis’ recruits: a Ku Klux Klan member who spurned his past beliefs but remained active in the Klan,” maintaining a front to provide information about its Long Beach branch. A rabid anti-Communist, and paid informant always strapped for cash, Slocombe ran 7 boats (“water taxis”) from Long Beach to Catalina Island, “where pleasure seekers could dance to the sounds of the Jimmy Dorsey and Glenn Miller orchestras.”

Slocombe, with 3 other men, including a Nazi operative on Lewis’ Most Dangerous List, were planning to disrupt a talk for San Diego Jews, by “snowstorming” it with thousands of anti-Semitic flyers. By 1938, “snowstorming”--dropping masses of leaflets from the tops of small buildings--had become American Nazis’ favorite propaganda method: viewed as more effective and less labor-intensive than stuffing individual mailboxes, papering car windshields, or pasting up trees and telephone poles in the middle of the night.

On the drive down from L.A., Slocombe was shown the operative’s “kike killer,” an 18 inch long, 2 ½ inch wide oak club with a leather thong. Instructions on its use: “You wrap it around your wrist and then poke it in the man’s stomach, and when he bends over, come down on top of his head with the flat side.”

Arriving in town, the men looked for tall buildings to drop flyers from while Slocombe, pretending to check a nearby roof, slipped into the office of a Jewish attorney, tipped him off about the snowstorm operation, and asked him to call the police and district attorney. The police seized the men and took them to jail. The Sargent knew about the setup; his men didn’t, believing they were arresting Communists.

After reading the flyer, one officer apologized to agent Slocombe. “This is a hell of a note that we have to pinch a guy that’s fightin’ the Communists. I wish I had read that before I took you to the station. This is good and I’m going to put one of these in my pocket.” He handed copies to the janitor. “Hell, they ought to give him a medal.” Nodding in agreement, the police passed the handbills around.