For Max Miller, it was over before it ever began. The young writer, “caught hard in the Renaissance of our generation,” confesses that “I wanted to be the great novelist. And yet no publishers ever come round begging me to write.” Thus, he muses at the end of his most famous novel, “that while the world whizzes around me, while men are made and unmade . . . I am content to stay here in this sunny port getting names, names, names. I am nothing—a nothing with lungs to keep me a mortal and with eyes for recording names.”

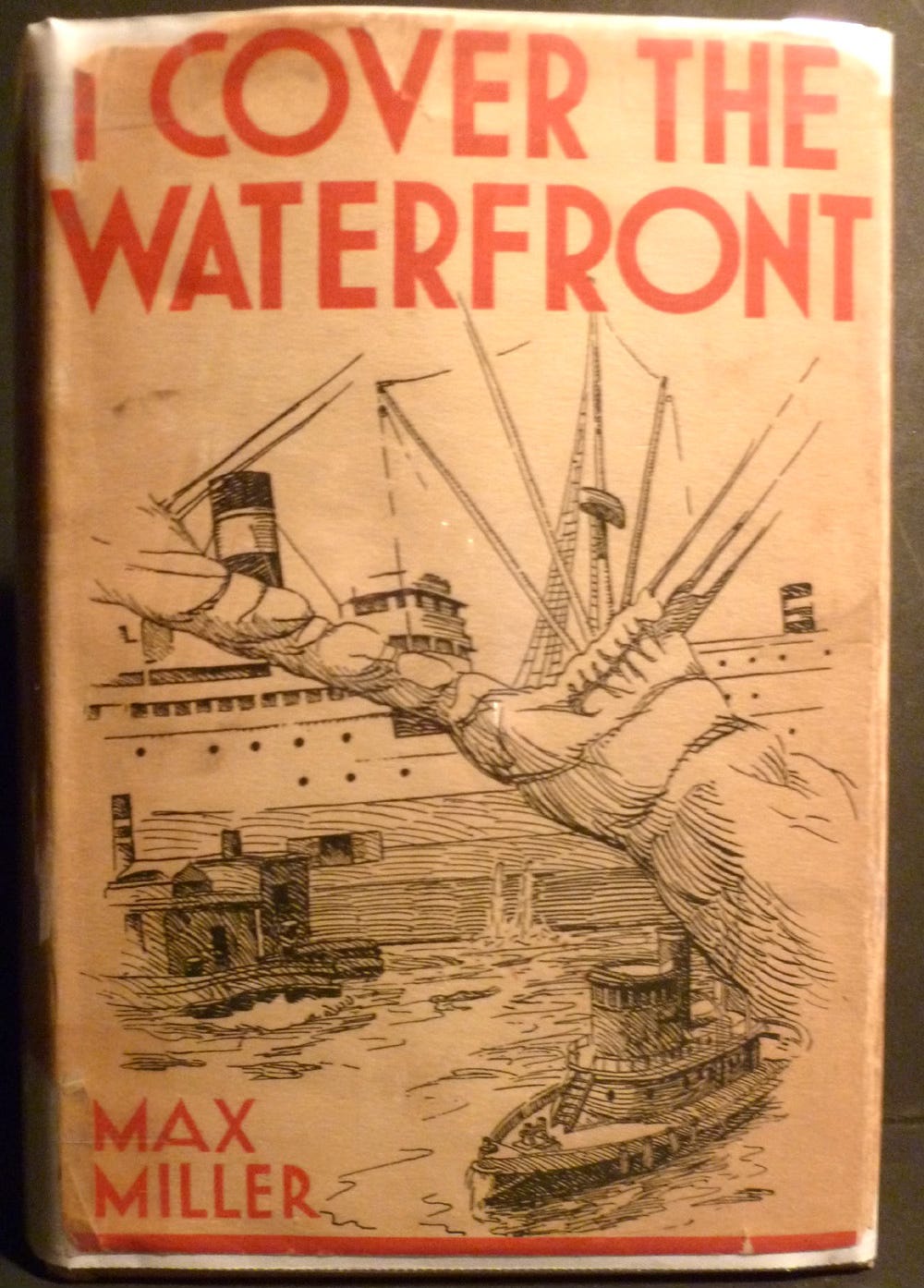

Of his most-praised book, the bard of San Diego finally observes that “the pieces refuse to stitch themselves together into a plot, into a novel with a hero and heroine, into a theme and a purpose. I lose . . .” And that sense of “dread” and failure along with a studied cynicism pervade Max Miller’s I Cover the Waterfront. Toward the end of his great San Diego novel of the thirties, he ponders how many others there may be who return home bitterly after not measuring up to the dreams they had stored in their ghostly hearts:

There must be thousands of us. Each train must be carrying home at least one of us. Each vessel too, must have at least one of us aboard. We are sick, we are ill, we are diseased. We have no message to deliver because we are too burning with our ambition to give messages. In our hungry desperation to see more than others see we over-focus our field glasses, and instead of creating a second sight we create a blur. We are suicidal, blind; we are clever, not clever enough. We are wise, but our wisdom is without direction. We lug it around only to annoy us.

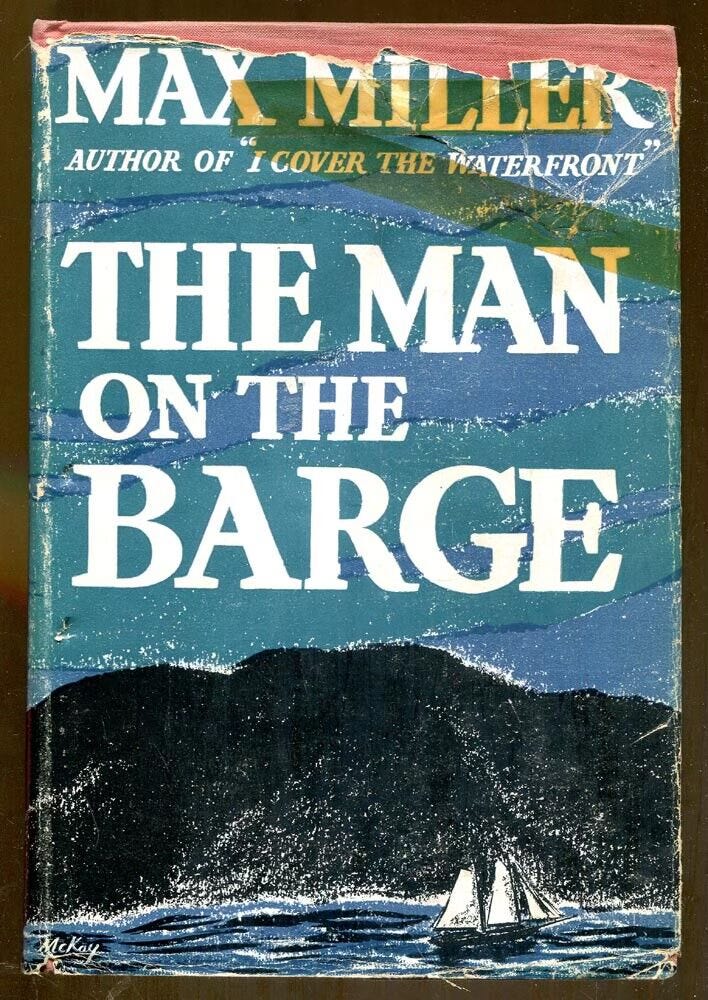

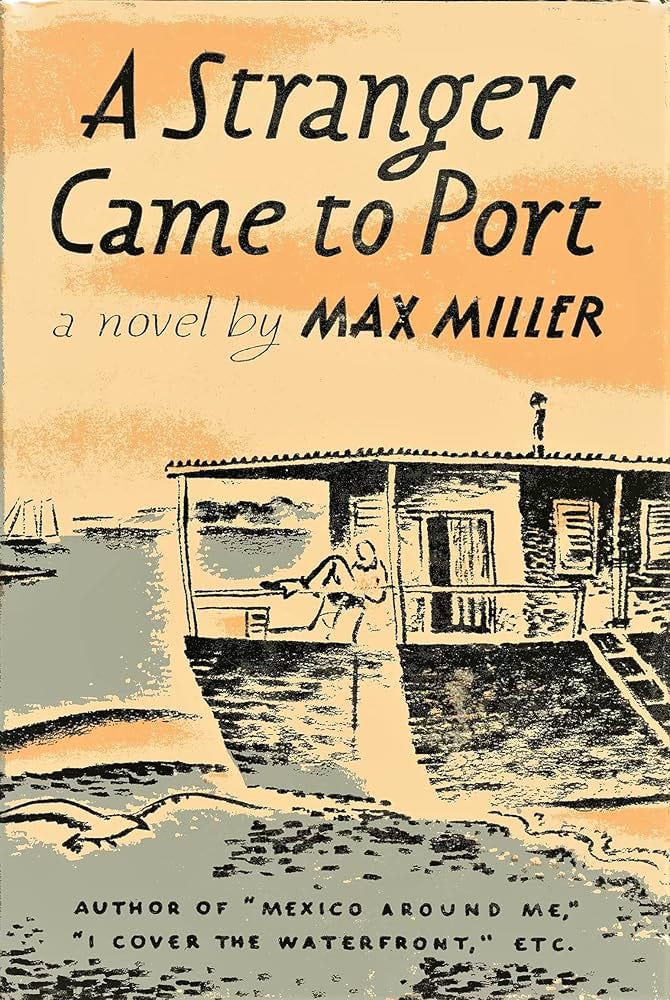

Despite his deep inner reservations, Miller was one of San Diego’s most prodigious and nationally recognized writers, author of twenty-eight books including The Man on the Barge, A Stranger Came to Port, and his best-known work, I Cover the Waterfront. Writing during the Depression era, Miller’s work spoke of alienation and unease underneath our perfect sun.

In an insightful San Diego Reader piece, “Who Was Max Miller?”, long-time San Diego journalist, the late Don Bauder describes I Cover the Waterfront as “a book of vignettes about San Diego’s waterfront — an area of seedy saloons, brothels, hard-toiling fishermen, hard-drinking dock workers, hard-bitten con men, and hard-up sailors that the preachers wanted to sanitize, and city fathers wanted to keep hidden.”

In his book, Miller’s disdain for tourists is clear as he acerbically notes their love of “hand polished shells” and “shoe-boxes in which the florists around here pack their tiny cacti plants for customers” and has fun mocking the rotating cast of indistinguishable characters who come to San Diego on boats and trains to get their packaged experiences, whether that be cheesy mementos or fishing trips.

Indeed, his brutal portrayal of henpecked Johnny Lafferty’s funeral, whose death is preceded by a humiliating descent from lobster fisherman to shore boat captain shuttling passengers to Navy ships to tourist guide in a “white uniform and a white cap,” who at his funeral had his ashes cast into the wind by his wife only to be blown back into the faces of the mourners gathered on his old vessel oozes with revulsion and contempt.

Miller contrasts scenes like these with vivid portrayals of the remote islands of San Diego’s coast that are home to elephant seals, huge flocks of birds, rattlesnakes, and the odd hermit and his eventual female partner forced upon him by the madame of the local waterfront brothel. Mixed in with these sketches are murders, suicides, liquor smuggling, and other grim aspects of life along the waterfront.

Some of the best writing in the book outlines the nitty gritty details of the work of tuna fishermen who labored in large teams, “the hooks flying everywhere and some of the men become badly cut up. They sometimes have their eyes put out, and now many of the men wear heavy masks of wire over their faces.” And the sardine boards where the narrator observes, “the sardine school to our starboard was nothing more than a wide sheet of phosphorescence. A man on the bow was signaling with his arms to Mederna at the wheel. The two men had to work fast as the school was likely to dart in any direction which pleased its fancy.”

Scenes like these along with descriptions of men waist deep in fish on the boats as the hauls came in or listening to the ocean for signs of a big school or exploding with boy-like enthusiasm over the opportunity to spear a swordfish evoke a long-lost San Diego of working people on the waterfront, in the packing houses, and at the dive bars by the water. Rereading Miller’s book makes me remember the nets I used to see tossed out to dry by the harbor when I was a little boy driving past the bay, back in the dying days of the industry.

Throughout his deadpan reportage and frequently cynical takes, the narrator holds onto some aspect of rugged romance about the work of the sea despite himself. It is a kind of San Diego grit that belies tourist images of the sunny port, then and now.

Despite this noir edge, though, Bauder observes that Miller was no Thirties radical. As opposed to the upstart young journalist Neil Morgan, he bristled against urban change in San Diego: “Morgan portrayed a postwar community beginning to experience big-city life. Miller wanted to keep San Diego small. He railed against tourism and tract homes.”

Many readers of Miller’s work think he never wrote anything better than I Cover the Waterfront, but not everyone was as kind. As Bauder wrote: “[Neil] Morgan, had a different interpretation. ‘I Cover the Waterfront was widely said among publishers to have been rewritten by a very beautiful literary agent in New York who was in love with Max at the time,’ says Morgan. ‘It was a nasty allegation, but it was a better book than any he wrote subsequently. I tend to believe the rumor of the publishing trade.’”

But on this summer day, I prefer to give Max the benefit of the doubt and remember him as the man whose best known-narrator oddly nestled up to a baby seal on the beach at night and told his readers that “the eye of a fish is a beautiful thing.” Max Miller may not have lived up to the literary giants of the Modernist literary renaissance he admired, but, despite his bitterness, he could still see something in San Diego that evoked a dream in the old working port:

Nights down here on the waterfront are not at all like daytimes. It is as if while we are away to supper somebody comes along and redecorates the whole shoreline. The lights along the embarcadero multiply in the water, and when a shoreboat noses along cutting the surface the lights multiply still more. So strange is the change here between nighttimes and daytimes that for all I know I too could have moved to Constantinople . . .

And to see this as a local, he reminds us, is much better than to come as tourists on an ocean liner like “shackled prisoners being transported,” unlike Miller who watched the “latest transfiguration of the cloud, the night clouds specially” feeling “aloof” from “the moneyed travelers” who don’t have the privilege of having “gone around and around and around the world while sitting with my cigarettes in this tiny tugboat room of mine.”

Note on the Summer Chronicles:

A decade ago, during my time writing for the OB Rag and SD Free Press, I penned a series of pieces over the summer that moved beyond the blog/column form to something a little looser and more open to improvisation and the poetic turn. Last summer, a health crisis intervened, but I made it through to the other side of that and here I am again, writing, word by word, breath by breath.

Below is the original preface for the first series of chronicles:

In the summer of 1967, the great Brazilian writer, Clarice Lispector, began a seven year stint as a writer for Jornal de Brasil [The Brazilian News ] not as a reporter but as a writer of "chronicles," a genre peculiar to Brazil. As Giovanni Pontiero puts it in the preface to Selected Chrônicas, a chronicle, "allows poets and writers to address a wider readership on a vast range of topics and themes. The general tone is one of greater freedom and intimacy than one finds in comparable articles or columns in the European or U.S. Press."

What Lispector left us with is an eccentric collection of "aphorisms, diary entries, reminiscences, travel notes, interviews, serialized stories, essays, loosely defined as chronicles." As a novelist, Pontiero tells us, Lispector was anxious about her relationship with the genre, apprehensive of writing too much and too often, of, as she put it, "contaminating the word." It was a genre alien to her introspective nature and one that challenged her to adapt.

More than forty years later, in Southern California—in San Diego no less—I look to Lispector with sufficient humility and irony from my place on the far margins of literary history with three novels and a few other books largely set in our minor league corner of the universe. Along with this weekly column, it's not much compared to the gravitas of someone like Lispector. So, as Allen Ginsberg once said of Whitman, "I touch your book and feel absurd."

Nonetheless the urge to narrate persists. Along with Lispector, I am cursed with it—for better or worse. So for a few lazy weeks of summer, I will try my hand at the form.