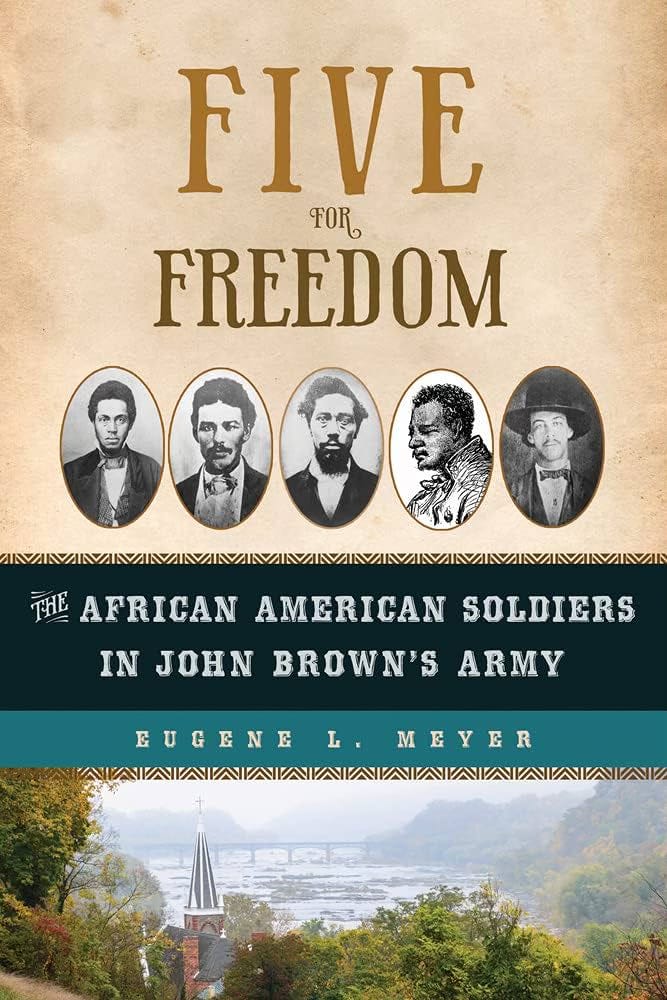

Five for Freedom: The African American Soldiers in John Brown’s Army by Eugene L. Meyer on Lawrence Hill Books, 2018

by Mel Freilicher

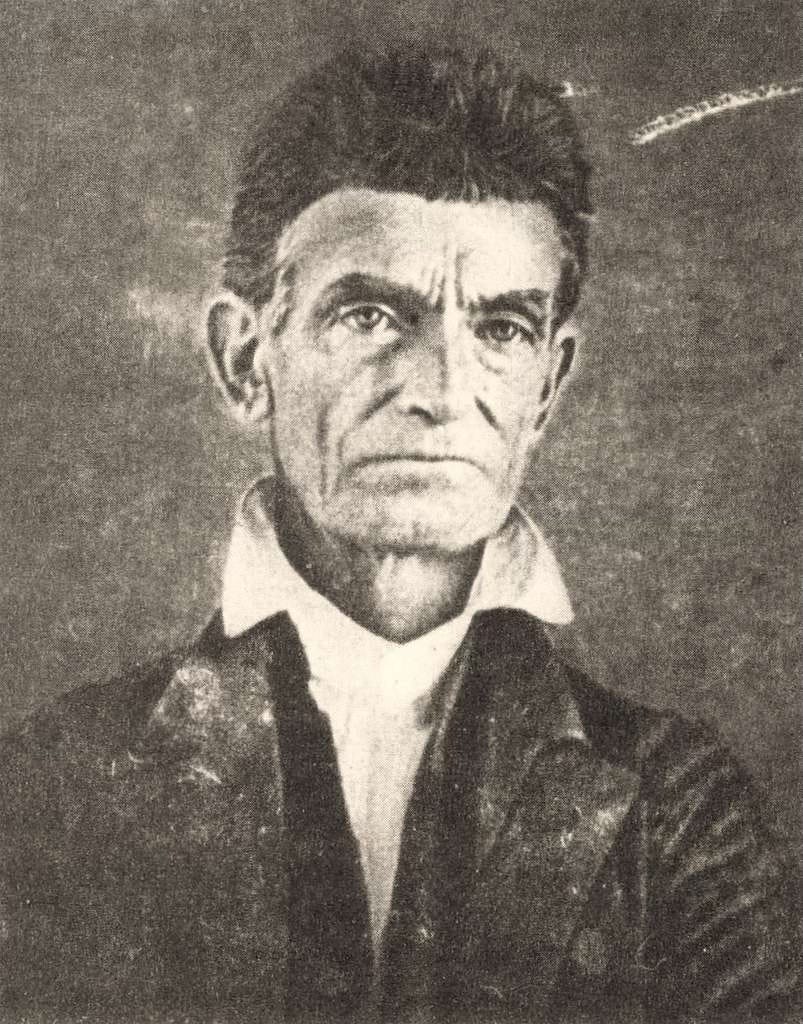

More than a month passed between the capture of John Brown and the seven men at Harper’s Ferry, and their execution for treason. In that period, John Brown wrote many eloquent letters which were widely published nationally in newspapers, and garnered tremendous sympathy for the cause. (Thoreau called him “an angel of light.”)

John Anthony Copeland, one of the African Americans in “the army,” would say he, like most of the other recruits, initially understood the plan was simply to rescue slaves and take them to Canada—certainly not to foment insurrection or provoke a shoot-out with farmers, militiamen, and U.S. Marines in a futile attempt to take over the federal arsenal.

John Brown was hanged not in the jailhouse courtyard, but in a more public space for all to see, as the judge at Harper’s Ferry mandated. The New Orleans School of Medicine offered to pay Virginia $500 for his remains “for dissection.” But Governor Henry A. Wise, who had asserted state jurisdiction over the bodies of the captured insurrectionists, chose to honor Mary Brown’s request to ship the remains of her husband north to their farm in upstate New York.

Of the other raiders who died at Harper’s Ferry, the remains of the white men, Weston Brown and Jeremiah Anderson, went to the medical college in Winchester. The remaining eight corpses, including four African Americans, were left in a pile on the town streets for a day. No cemetery would take them. Instead, two local men were hired to load the corpses into a wagon. Driving half a mile up river, arms and legs dangling over the side, two wooden storage boxes were buried in unmarked graves in an out-of-the-way site.

Having previously read and written about the sparse and puritanical life of John Brown and family, I was looking for facts like these which I hadn’t known. The unusual focus on the 5 African Americans of Brown’s 18 raiders (including two of his sons who died in the battle) seemed quite promising.

Clearly, my Meyer review would need to herald some basics of John Brown’s saga, even if they weren’t really covered in the text: especially the consequences of the Kansas-Nebraska Act of 1854, which repealed the Missouri Compromise. Newly admitted states would now become free or slave, not according to geographical location, but by a vote of fiercely clashing residents--not surprisingly, Lawrence (home of the state university, opened in 1866) was an abolitionist center, Leavenworth its nemesis.

The common assumption was if Kansas went for slavery, all the other territories would, too. I remembered David S. Reynolds’ description of the zeitgeist in his book, John Brown, Abolitionist: The Man Who Killed Slavery, Sparked the Civil War and Seeded Civil Rights which he considered more typical of the antebellum South: “eye-gouging, bowie-knife stabbing and scalping, hanging, burning over slow fires, whipping, tarring and feathering.”

Not only were individuals on both sides kidnapped, ambushed, and murdered but whole towns were sacked. Moving to Kansas in 1855, John Brown dove right into the violent vigilantism between Free Staters and pro-slavery forces, retaliating, with several sons, against the pro-slavery settlement of Pottawatomie, by brutally hacking up and butchering Drury Doyle and two of his sons.

Turns out Meyer barely touches on the “Secret Six,” the group of eastern male financiers of Brown’s Harper’s Ferry invasion, only remarking their identities were later discovered, but none was ever punished. One, Thomas Wentworth Higginson, Unitarian minister, Emily Dickinson’s friend and “preceptor,” went on to command the first all free black male regiment of the Union Army. I also recalled when John Brown was captured, Frederick Douglass, and four of the “Secret Six” temporarily fled to Canada.

FIVE FOR FREEDOM…

Four of the five African Americans who chose to raid the federal arsenal were mixed race, and free men. Only one, Shields Green, was a fugitive slave. Claiming to be descended from African royalty, he’d met John Brown in Rochester, New York, where he was unsuccessfully trying to convince Frederick Douglass to join the raid. Douglass argued Brown was “going into a perfect steel trap. And that once in he would never get out alive.” But Green, who was staying with Douglass at the time, decided to “go with the old man.”

Osborne Perry Anderson, the sole African American survivor, was born free in a small town in rural Chester County, in southeastern Pennsylvania. Adjoining Philadelphia, and heavily influenced by its Quaker population, the County was a hotbed of abolitionism, containing many Underground Railroad stations; the county seat was the home of some 300 free blacks.

Anderson went to public school there but was part of the mass migration to Canada after the passage of the infamous 1850 Fugitive Slave Act (the “Bloodhound Bill,” as Frederick Douglass called it) which precipitated an exodus from every northern city with a sizable black population. 120 members of the Baptist Colored Church in Rochester, 100 from the Colored Baptist Church of Buffalo, and 200 from Pittsburgh rushed across the border.

Within three months, the Pennsylvania Freeman estimated some 3,000 African Americans had crossed into Canada, including more than a third of Boston’s black population. Most landed in the southwestern corner of what is now Ontario; many, like Osborne Anderson, stayed in Chatham, a naval shipyard dating back to the 1790s.

Before that, a continuous trickle of runaway slaves had found their way to Canada. In 1830, mob violence and the institution of rigid black codes in Ohio culminated in the exodus of nearly 2000 blacks from Cincinnati to Upper Canada where land was cheap. Slavery was abolished in 1833; black men could vote, own property, serve on juries and in the military.

Returning home to Chatham, Osborne Anderson wrote A Voice from Harper’s Ferry, an insider’s critical view of Brown’s organizing abilities. The plan to arm local slaves in the hope of starting a mass insurrection was unrealistic in an area in Virginia which lacked large plantations. Also, the raiders had never really talked about staying at Harper’s Ferry—certainly not holing up there.

Dangerfield Newby’s situation was the most urgent: one of 11 children born to Henry Newby, a white man, and his common-law enslaved wife, Elsey Pollard, who was said to be of Native American, African, and European descent. In 1858, Dangerfield’s father took him and several siblings to Ohio: just living there made them free.

Two years earlier, a State Supreme Court decision about an enslaved worker from Kentucky who’d been hired out by his owner, and established Ohio residence, declared the “chains of slavery must crumble to dust when he who has worn them obtains the liberty from his oppressor, and is afforded the opportunity of placing his feet upon our shore.”

Dangerfield had a strong relationship with Harriet, a slave with whom he had children, probably seven. Trying to negotiate for their purchase, using his trade and skills as a blacksmith to earn money, Dangerfield had saved nearly $742 (almost $21,000 in 2017 dollars). Not enough to buy his wife and even one child! Meanwhile, her owner was threatening to sell her down the river. Meyer writes, “Dangerfield could not have foreseen that he would be the first fatality among the raiders, that Harriet and their children would indeed be sold south.”

The final two “mulattos,” John Anthony Copeland and Lewis Sheridan Leary, were related by marriage: two Leary sisters had married two Copeland uncles. Both men had migrated, several years apart, from North Carolina to Oberlin, Ohio. And both had rather illustrious ancestry.

Lewis Sheridan Leary’s father was a free man: his own father was of mixed Irish and Croatian Indian blood; his mother, a tri-racial woman whose father had been a Revolutionary War soldier. Becoming rich with a wholesale business, Lewis’ father had actually been a slaveholder himself, but had given money to his slaves to buy their freedom.

John Copeland’s father was the son of a white master who died when John was 8, freeing him but leaving no money. His mother, descended from the Revolutionary War general, Nathanael Greene, was a light-skinned free woman.

Following the self-styled preacher, Nat Turner’s, 1831 rebellion in Virginia—when more than 50 slaves had been convicted and executed by twenty judges, all slaveholders—North Carolina was among several Southern states vigorously participating in an ever-expanding legislative maelstrom to restrict the movements and liberties of all blacks, free or enslaved. Prohibitions included preaching the gospel, attending nighttime religious services without permission, and learning how to read and write.

Required to carry papers attesting to their legal status, there was always the threat that away from home, North Carolina’s free blacks could be kidnapped as fugitive slaves and sold into bondage. When the Copelands wanted to leave for Ohio, they needed to carry letters of transit from white patrons attesting to their good character.

To me, the most surprising (and least depressing) section of this book concerns the central role of Oberlin, which Meyer describes as virtually a utopian community: settled mostly by New Englanders with a Puritan ethic and strong moral convictions against slavery. “What the newcomers found shocked them. People of both races walked together, prayed together, went to school together. They were even buried together.”

In effect, the whole town of Oberlin, where both Copeland and Leary first met John Brown, was one major Underground Railroad station. Residents refused to celebrate the Fourth of July because the Declaration of Independence excluded blacks. Their big holiday was August 1, the date slavery was abolished in the British colony of Jamaica.

Oberlin, the first college in the country to admit African Americans, (Brown’s father, Owen, was a trustee from 1835 to 1844), played a major role in both men’s lives. John Copeland attended Oberlin’s preparatory department for one year. Lewis Leary met his wife there who left school when their first child was born. After Lewis’ death, his widow, Mary, married Charles Langston, and moved to Kansas: in time, becoming the grandmother of Langston Hughes.

Meyer vividly describes Ohio’s vehement reactions to the Fugitive Slave Law. Prominent politicians, such as Massachusetts born Senator Benjamin Wade, suggested Ohio should secede rather than acquiesce to the Act’s noxious terms. Citizens of one township passed resolutions holding the law “in utter contempt…sooner than submit to such odious laws we will see the Union dissolved.”

A meeting in another Ohio town asserted any person accepting the office of commissioner or marshal under the bill was “a man utterly devoid of humanity and a fit associate of hangmen.” Senator Chase led a meeting which resolved that “Disobedience to the enactment is obedience to God”: presaging a Martin Luther King, Jr. pronouncement.

Outrage was widespread over the north and western states. The Common Council of Chicago, by a vote of 10 to 3, adopted resolutions denouncing the Fugitive Slave Act, declaring its supporters “fit only to be ranked with the traitors, Benedict Arnold and Judas Iscariot.” In The Coming of the Civil War, author Avery Craven also points out the Council refused to require the police to render any assistance for the capture of fugitive slaves. (Viva Sanctuary!)

Two Oberlin students witnessed the kidnapping of runaway slave, John Price, who had been living and working with black laborers there for two years. Tricked into being taken captive, he was whisked off to a train station to be sent to Columbus then back to Kentucky.

Within hours, a swarm of local residents—estimates range from two to six hundred—surrounded the hotel where Price was being held. Some tried to negotiate with the captors; others attempted to arrest them. John Copeland urged Price to jump from the attic window, threatening to shoot anyone who tried to interfere.

While the abolitionist crowd (which included Lewis Leary as well as several professors) milled outside, two groups of young men stormed the hotel. Three white Oberlin students went through the front door while Copeland and two others used a nearby ladder to climb to a second story balcony in back. Reaching the room where the marshal was holding Price, they forced his release, taking him out of the building, with nobody being hurt.

Copeland, among others, including two of his uncles, was under federal indictment, but he couldn’t be found, and was never arrested. Of the total indicted, 25 were from Oberlin, 12 from nearby towns; 12 were black. Several were found guilty, fined and jailed but a deal was finally struck: the County dropped the kidnapping charges, the U.S. attorney dropped all other charges; those still in jail were released.

Brown had appeared at key moments during the 1859 trial, and Leary was “mesmerized by his eloquence and passion.” A month after the release of the prisoners, Brown’s son, John Jr., was in Oberlin, and in touch with Leary. When Lewis Leary abruptly left town to join the raiders, he deliberately didn’t inform even his wife of his destination.

Just ten days after the runaway slave, John Price, was rescued in Oberlin, a remarkably similar event took place in Chatham, Canada in which Osborne Anderson, and probably John Copeland, too, participated. (It was believed Copeland took Price to Chatham where John Brown held a mass meeting the year before.) An individual who claimed to be the owner of a ten-year-old free boy of color, Sylvanus Demarest, was seen boarding a train with him—with the intention, it turned out, of bringing him back to the states to sell into slavery.

When the Grand Western train carrying these 2 individuals stopped for water, the Chatham Vigilance Committee, of which Anderson was an officer, swung into action. An estimated 100 to 150 black men and women intercepted the train; several armed members boarded it, rescuing Sylvanus.

The railroad pressed charges against 7 of the rescuers, 2 white and 5 black. Among them was Isaac Shadd, who’d been given temporary custody of the boy. The presiding judge authorized fines rather than jail sentences, noting “the force of a higher law” than those on the statute books.

A chief advocate for the accused was Isaac’s sister, Mary Ann Shadd, the first female black editor in North America: Osborne Anderson’s childhood friend, and later, neighbor in Chatham, uncredited editor of his Harper’s Ferry account, and Osborne’s employer on Provincial Freeman (its masthead proclaiming “Self-Reliance is the True Road to Independence”).

Although two men were nominally listed as its editors, “there was little doubt in the community that it was Mary Ann Shadd’s newspaper.” She was also an officer of the Chatham Vigilance Committee (listed only by her initials).

Her family had originally moved to West Chester so Mary Ann and her 12 siblings might attend Quaker schools. Her education would have included instruction in religion and philosophy, literature, writing, basic mathematics, Latin and French, and the mechanical arts. And Mary Ann was taught the equality of not only the races but the genders. Her white teacher and the head of the school, Phoebe Darlington, was a delegate to the 1838 Anti-Slavery Convention of American Women.

While public education became the norm in the nation’s urban centers, free blacks were consistently excluded from these institutions--the responsibility resting with black self-help groups and white philanthropies.

Before moving to Canada at age 28, Mary Ann taught in a number of schools in Philadelphia (where less than two percent of the black working women were in professional occupations such as teacher or musician) and New York: typically, her first school there was impoverished, located in the basement of a black church, serving close to 900 students.

Mary Ann Shadd was born free to a black mother and mulatto father, a prosperous shoemaker and boot manufacturer, and conductor on the Underground Railroad. Her paternal great-grandfather, a Hessian soldier (one of nearly 5,000 who deserted or resigned from the British army and settled in the United States) wounded during the French and Indian War, married into the black family that nursed him back to health.

After Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation, Mary Ann Shadd Cary, now a widow with two children, and Osborne Anderson were both actively recruiting in Indiana and Arkansas for black regiments in the Union army. It’s been suggested Osborne joined the army, but Meyer states there’s no documentation of any military service.

Buying a house in Washington D.C. in 1869, Mary Ann became a public school principal, and enrolled in Howard University’s law school that year, finally receiving her degree in 1883—the second woman to do so. She wrote for the newspapers, National Era, and The People’s Advocate, and organized the Colored Women’s Progressive Franchise.

Joining the National Women’s Suffrage Association, she worked with Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton. Trying to register to vote in 1871, a seven-member board including two elected black officials turned her down.

Having learned this much, I ordered a scholarly work from Amazon: Mary Ann Shadd Cary: The Black Press and Protest in the Nineteenth Century. When it arrived, I was surprised to discover on the back cover its author, Jane Rhodes, was in the Ethnic Studies Department. at UCSD. Her name was vaguely familiar, but I had the strong conviction she was no longer there. Sure enough, the copyright is 1998, and she’s now listed as faculty at the University of North Carolina.

Although I was a longtime lecturer at UCSD and didn’t interact with many faculty outside (or within) the Literature Department, I had some key, well-placed friends, and knew quite a bit of gossip. One thing I knew for sure: until rather recently, this university had a very tough time keeping black faculty. Ethnic studies didn’t exist as a program, let alone a department, for decades after they got the academic green light in 1969—once the mothership, Berkeley, created such a department.

Most of that time, I was simultaneously a lecturer at San Diego State. For all its problems, SDSU was much more a working class school: establishing small but separate Afro-American, Mexican American, and Native American Studies Departments in the early ‘70s, and allegedly the first Women’s Studies Department in the country; something UCSD never did. Very late in the game, a minor in women’s studies was amalgamated with gender studies to create a hybrid program.

UCSD’s racist apotheosis came in 2010 with the infamous COMPTON COOKOUT (referenced in the movie, Dear White People): a mega-party, mocking Black History month—and not because of its token nature—thrown by frat members, many of them Asian. (To be fair, Alicia Garza, cofounder of Black Lives Matter, also graduated from UCSD eight years earlier.)

With no frat row on campus, the “bros” tend to live in awful nearby complexes. In a particularly oversized one, the “cookout” was scheduled to occur in different apartments: each bearing its own unique racist theme. Invitations went out online, replete with photos of students in blackface and fright wigs.

Instructions included how to act black: women were supposed to have compound, made- up names, garish makeup, wigs and long fingernails which they shook a lot. It was suggested they dress like ho’s—slutty outfits enumerated in detail.

A certain number of the UCSD “community” was outraged, a petition was started. In response, another petition with about an equal number of signers circulated, exclaiming, hey! What’s the big deal? Can’t you take a joke? (Happily, the two female editors of the school paper, my students at the time, did a magnificent job in dissecting what was wrong with that picture.)

The situation escalated dramatically until school ended that year. Tension was already high when a show broadcast on campus closed-circuit TV by the school’s satire paper (which had been funny a very very long time ago) lauded the Compton Cookout: highlighting photos from the invite and soiree itself and using the N-word seemingly as often as humanly possible.

(Not long afterwards, that show was cancelled because the host was allegedly being given a blow job under the table while broadcasting. But when the Associated Students organization tried to cancel the paper’s funding, its editors promptly enlisted the aid of the ACLU.)

Then the famed noose was found hanging in the library! The “what’s the big deal?” group reiterated their cries. About a month later, the alleged noose-maker confessed in an anonymous letter to the school paper. It seems she (who claimed to also be a member of a minority group) and some friends had found a short piece of rope on the ground while walking to the library.

Amazed at how easily it could be turned into a noose—because it was so short, get it!—they just forgot about it, assiduously studied, then left it on a table in the library. Someone must have found it and actually hung it from a high shelf! It was announced this student was suspended for a quarter.

I kept ranting to my students, “This is a failure of the education system,” believing or wishing to believe many undergrads didn’t even understand the semiotics of a noose in this context. (UCSD, founded on the site of the long-established Scripps Institute of Oceanography, has always been a science-oriented school, with a huge number of engineering students.)

Some students, afraid to sleep in their dorm rooms, were camping out at the school’s Cross-Cultural Center. One black, gay student, a bright, handsome, track star (thus popular), told me the administration had installed in hotel rooms some non-white students who were afraid of their roommates—keeping the threatening roommates in the dorms. This was never made public. Then a white hood was placed over the statue of Dr. Seuss (major donor to the school) which under other circumstances, I probably would have found funny.

The Black Student Union presented a rather gargantuan list of demands to the administration, then cut it down. As far as I know, only one or two were granted, creating more administrative positions concerning minority hiring—none about admissions (which had been dealt a horrendous blow in the ‘90s, when the heinous black regent, Ward Connerly, wiped out affirmative action).

Ah, well, posthaste back to Mary Ann Shadd! Aside from other biographical details, the opening sections of this study are intriguing because they discuss how slavery was handled in different upper Southern states.

Some scholars argue, “Delaware’s form of slavery was unique among states in the upper South”: allegedly blacks were viewed simply as an alternative form of labor. Rhodes points out the increasing numbers of free blacks in Delaware. By 1810, 76% of Delaware’s African Americans were free; by 1850, only 11% of the state’s black population were in bondage.

But aside from the usual dangers attendant on free blacks trying to travel anywhere in the South, Rhodes also examines the lack of educational opportunities in Delaware. Quakers established an African school in 1798 which offered instruction in reading, writing, and arithmetic, one day a week. Little changed in the next 20 years.

Further, Delaware officials became increasingly concerned with halting the growth of the free black population: laws were passed preventing reentering the state if they left for more than 6 months. In addition, free blacks from other states were denied entry altogether. Employers could be fined five dollars for every day they hired a non-resident person of color.

One of the largest groups of the American Colonization Society’s “back to Africa” movement was formed in Wilmington in 1824, when Mary Ann was a year old. The Society itself was an odd coalition of northern abolitionists and southern politicians, like Kentucky slave owner Henry Clay, who assumed slavery would be preserved once free blacks were repatriated to Africa.

Some abolitionists in the Society simply felt life would always remain too dire for black Americans. Others rationalized relocation of free blacks would offer the opportunity to govern themselves, and eventually lead to the end of slavery.

Many Society members were the Shadds’ white neighbors and business associates. They “blended abolitionist rhetoric with anti-black sentiment when they declared at their first annual meeting, the slave population ‘deprecates our soil, lessens our agricultural revenue, and like the lean kine of Egypt, eats up the fat of the land.’”

Delaware’s oppressive environment became too much for Abraham and Harriet Shadd; moving to Pennsylvania, they settled near the Mason-Dixon Line at the Maryland border, not a region particularly hospitable to free blacks. Beginning in the 1820s, Philadelphia saw numerous riots and anti-black violence. In the 1830s and ‘40s, new European immigrants displaced blacks from semiskilled and unskilled jobs.

Still, educational opportunities were greater for Mary Ann and her siblings: Quakers, African American churches and benevolent societies offered a limited array of schooling options. Although state law established free public education in 1818, not until 1829 was the first black public school built in Philadelphia.

The Philadelphia Female Anti-Slavery Society is often cited by scholars for its inclusion of white and African American women as leaders and members. But, Jean Sodelrund writes in an essay, “Priorities and Power,” the Society lost much of its organizing impetus after Pennsylvania Hall was burned down in 1838, 3 days after it opened: a lofty, 3000 seat auditorium with plush, upholstered sofas and seats in blue damask, built by abolitionists for meetings and rallies.

A mob broke into the empty building, setting fire to draperies and furniture. Volunteer fire companies doused the adjacent structures but did nothing to stop the burning of the Hall. Only after the mob headed for the center of the African American Community, attacking the First African Presbyterian Church, and a colored orphanage, did the mayor send in the police. At the trial, the county defended itself, accusing the abolitionists of causing the fire by the provocative act of hosting an interracial meeting.

In Pennsylvania, Mary Ann’s father had been elected President of the Third Annual Convention for the Improvement of Free People of Color, where he vigorously opposed the back to Africa movement. Declaring black Americans should focus their attention on racial improvement through education and temperance, expressing his Garrisonian leanings by calling for the immediate end to the immoral institution of slavery.

Following in her father’s footsteps, Mary Ann viewed expatriation as traitorous abandonment of the abolitionist cause. However, passage of the Fugitive Slave Act occasioned renewed interest in emigration to Africa, the West Indies, and Canada.

In September 1851, 53 delegates assembled in Toronto to advocate for black emigration to Canada. Most of the delegates were lesser known activists from the cities, towns and hamlets of Canada West. As an American, Mary Ann’s father, Abraham, was in the minority. A new black political establishment emerged in this meeting: Mary Ann met many of the major Canadian activists who made a strong case for a more prosperous future for American blacks.

Frederick Douglass continued to oppose emigration: “It is idle—wore than idle, ever to think of expatriation or removal. We are here, and here we are likely to be…this is our country,” he proclaimed. But only a few days after the Toronto conference, Mary Ann Shadd decided to emigrate.

Offered a position in Toronto (which had a small, but vital, burgeoning black community), Mary Ann decided instead to open a school in a more remote black community, at Sandwich, on the western shore of the Detroit River. Jane Rhodes goes on to explore the relations and difficulties Mary Ann faced with some of the black male leadership in Canada, and her eventual return to the U.S.

Yesterday, at the new-ish, rather lovely, nearby branch of the SD public library, which I’ve been haunting in order to fanatically devour Patricia Highsmith novels, I came across Eric Foner’s massive tome, Reconstruction: America’s Unfinished Revolution, on sale for $1.

Before buying it, I opened to a random entry in the Index for Elizabeth Cady Stanton (none for Mary Ann Shadd), and came across this startling passage:

As her regard for her erstwhile allies waned, Stanton increasingly voiced racist and elitist arguments for rejecting the enfranchisement of black males while women of wealth and culture remained excluded. “Think of Patrick and Sambo and Hans and Ung Tung,” she wrote, “who do not know the difference between a Monarchy and a Republic, who never read the Declaration of Independence...making laws for Lydia Maria Child, Lucretia Mott, or Fanny Kemble.”

In May 1869, Foner tells us, the annual meeting of the Equal Rights Association, devoted to both black and female suffrage, “dissolved in acrimony” resulting in two rival national organizations which wouldn’t be reconciled until the 1890s.

Oy, humanity!

Mel Freilicher retired from some 4 decades of teaching in UCSD's Lit. Dept./ writing program. He was publisher and co-editor of Crawl Out Your Window magazine (1974-89), a journal of the experimental literature and visual arts of the San Diego/Tijuana region. He's been writing for quite some time. He is the author of The Unmaking of Americans: 7 Lives, Encyclopedia of Rebels, and American Cream, all on San Diego City Works Press.