John Sloan: Painter and Rebel by John Loughery on Henry Holt & Co., 1995

By Mel Freilicher

1

On the wintry night of January 23, 1917, John Sloan, Marcel Duchamp, Charles Ellis (a premier actor in the Provincetown Playhouse and former student of Sloan) along with four other friends illegally entered the side door of the Washington Square Arch at the foot of Fifth Avenue, climbed the inner spiral staircase, and proceeded through the monument’s trap door to the roof for an impromptu picnic-- supplied with food, balloons, candles, Chinese lanterns, cap pistols, and bottles (some, hot water).

The inspiration came from another of Sloan’s students, Gertrude Drick, a flamboyant Village poet who was known by the name Woe (“I’ve always wanted to be able to say ‘Woe is me.’”) Tying the balloons to the parapet, Gertrude read their proclamation. Consisting of nothing but the word “whereas” repeated over and over until the final words declared henceforth, Greenwich Village would be a “free and independent republic,” claiming the “protection of President Wilson as one of the small nations.”

On the eve of U.S. entry into WWI, villagers saw themselves as defiantly different not only from other Americans but even from other New Yorkers. As John Loughery points out, in an area of low rents and relaxed mores, of minimal interest in conventional success (and what Mary Heaton Vorse termed “the curse of conformity”), Villagers perceived this as yet undeveloped part of the city as a ”spiritual haven,” in the words of one neighborhood woman.

Before the end of that winter, Sloan would be involved with Duchamp, William Glackens and many others in the formation of the Society of Independent Artists, designed to make the work of Villagers—wherever they lived—better known to art lovers and potential buyers. This organization, rebelling against the stuffy National Academy of Design’s neoclassical criteria for exhibiting work, would engage Sloan’s energies, as its Director for 27 years, long after most contemporaries had abandoned the cause.

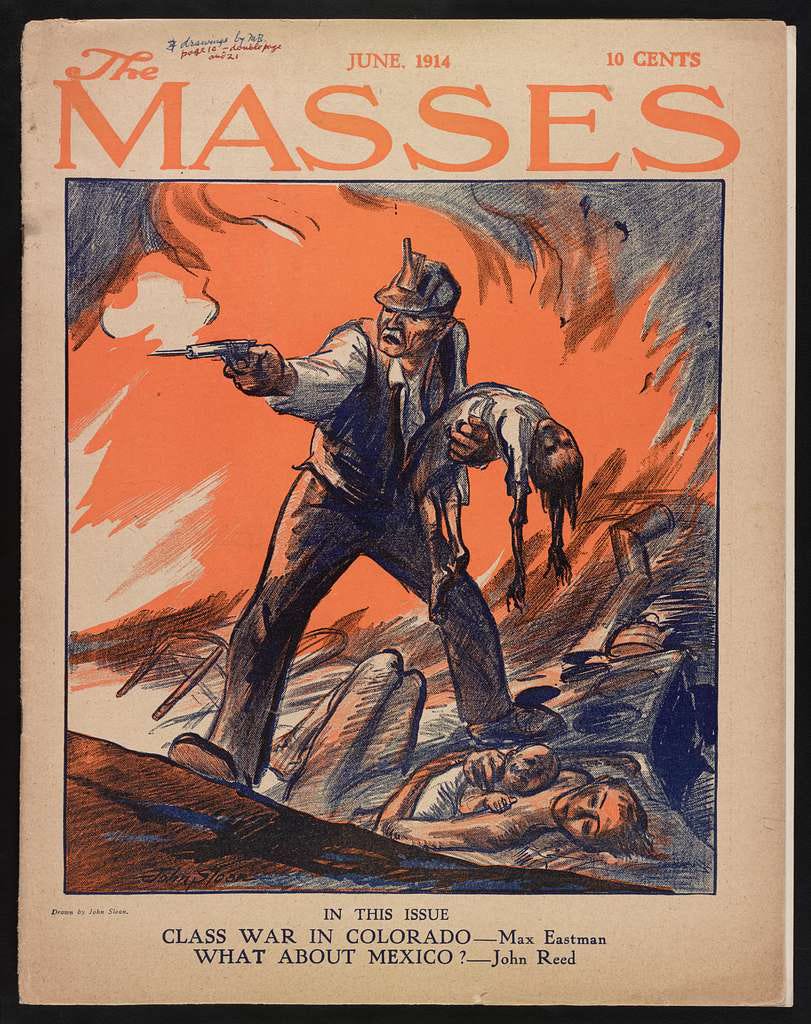

Before Sloan could earn a living as an artist, he taught full-time at New York’s Arts Student League for two decades, and was elected its president in 1931. First as a contributor, then as the art editor of The Masses, “today an especially revered forum in the history of left-wing political journalism,” Sloan provided many of the periodical’s most vivid illustrations: four covers and 32 drawings in 1913 alone.

Aiming for a “jaunty intellectuality, a devil-may-care marriage of levity and principle,” in Loughery’s words, the new magazine remained unaffiliated with any party—some Socialists objected, despite already having their own periodicals. With wealthy patrons like Aline Barnsdall (the California heiress who commissioned Frank Lloyd Wright’s Hollyhock House), Mable Dodge, and the publisher, E.W. Scripps, The Masses was unencumbered by debt, meaning no binding ties to advertisers.

Intending to represent a broad range of progressive news and ideas in a visually impressive assemblage of high quality drawings (usually presented as independent works), cartoons, poems, stories, jokes, satire and commentary, the editors developed fine techniques of reproduction and an uncluttered design which showed the artwork at its best.

An active member of the Socialist Party of America (sometimes publishing illustrations, many of which he frankly viewed as propaganda pieces, in its daily newspaper, The Call), Sloan allowed himself to be nominated twice as candidate for State Assembly. Leaving the Party when many of its members supported U.S. entry into WWI, he remained a lifelong anti-capitalist.

2

Sloan and his wife, Dolly moved to the village in 1912. Before that, for 8 years they’d lived in a small, top floor apartment on West Twenty-Third Street, in the Chelsea district bordering the Tenderloin, where the reputable and seamy overlapped and interpenetrated: with its taverns, restaurants, gambling dens, many affordable shops with enticing picture window displays, movie parlors, dance halls, burlesque stages, brothels, streetwalkers (largely but not exclusively women), cardsharps, con men, quaint boarding houses.

Their skylight afforded a panoramic view that “spanned the architecture of Richard Morris Hunt, the street kids of Jacob Riis’ photographs, great libraries, and massive tenements—constant reminders of profitable successes and abject failure, of pleasure and need.” (Sloan described Sixth Avenue as having a “Coney Island like quality in 1907.”) Awed, he aimed to capture the city’s atmosphere which “contained squalor and exuberance at one and the same time, and moments of anguish and exhilaration not antithetical but necessarily linked,” as Loughery states.

The majority of drawings, prints, and paintings from Sloan’s Chelsea years are glimpses of his neighborhood, street scenes, interiors. “The theme of the window frame, and the very act of looking inevitably became almost a preoccupation for Sloan.” The congestion of the city and the arrangement of apartment buildings in orderly rows abutting each other enabled him to peep into neighbors’ homes without being detected.

More central to his work were extensive walks--the idea of the gaze in motion--tracked in voluminous detail in Sloan’s diaries. His main subject: mostly women passersby and their activities—walking to the theaters, window shopping, pausing to discuss displays of goods, and above all else, watching one another. Realized not as types but as individuals. Integral parts of the chaos and excitement of the crowded streets.

After moving to the Village, Sloan further developed rooftops and city skyline as subjects. Rooftops functioned as extensions of the homes of New Yorkers—what the critic Susan Fillin-Yeh referred to as liminal spaces—not private or interior, and not public like the street: residents hung their laundry, styled their hair, and slept there on very hot nights. “Work. Play. Love, sorrow, vanity, the schoolgirl, the old mother, the thief, the truant, the harlot…” Sloan wrote, “These wonderful roofs of New York bring me all of humanity.”

3

When the couple first moved to New York from Philadelphia, six years after marrying, Sloan had already established himself as a significant illustrator, graphic artist, and promising visual artist. He’d taught himself etching and was soon working as a freelancer. Especially after 1897 when the technique of running halftone images on rotary presses was all but perfected, and photography ascendant in the world of journalism, John was asked to provide illustrations for many “little magazines,” sometimes to accompany a story, such as by Kate Chopin or Mary Heaton Vorse.

Offered a full-time position as illustrator at the then conservative paper, the Philadelphia Inquirer, he was later hired as assistant art editor of the Philadelphia Press which was just as unquestioning of the political status quo. (The Inquirer’s coverage of Coxey’s Army’s march of the unemployed to D.C. during the second year of the country’s worst depression, and the Pullman strike debacle had been viciously anti-labor.) But the Press had a female Washington correspondent, a reputation for a more intellectual staff, fewer racist cartoons, and a less strident tone.

Effects of Sloan’s early training at the then moribund Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts were chiefly countered by the influence of his first, and most significant, mentor and friend, Robert Henri. A charismatic and witty conversationalist, the 27 year-old painter had just returned from living 3 years in Italy and France, when Sloan met him in 1892. The circle of male painters, just a few years younger than Henri, which gathered around him formed the nucleus of John’s social life; Henri was instrumental in this group gaining entrée into gallery and museum shows

Henri viewed the “art for art’s sake” movement as a trap for young artists who were “afraid to engage the more robust spirit of their own time.” The art of the new century was going to have to be less effete, less genteel, more energetic and inclusive of the range of modern experience, little of which entered into instruction in most art schools. The painters discovered their shared passion for Walt Whitman, deceased only 10 months earlier in nearby Camden. Sloan’s visual presentations of the streets of New York were often written about in relation to the spirit of Whitman’s Leaves of Grass

4

Not surprisingly, John’s family, especially his sisters, were none too pleased when, at age 27, he married an alcoholic prostitute, even if they chose to never look closely into Dolly Wall’s past. Born into a once wealthy family whose fortunes were declining, Sloan had every expectation of going onto the university with a scholarship, until his father’s mental breakdown forced him to leave high school in his last year to help support the family.

First meeting Dolly in a brothel where she worked part time (unlike many, she had a day job), she came over and sat on Sloan’s lap. Loughery reports, “This didn’t trigger any of the anxiety that such episodes usually did” for the introverted young illustrator. “Alert, and attractive,” Dolly was brown-haired, brown-eyed, “diminutive…almost doll-like at four foot nine—with a thin waist and warm smile.”

Sloan initially found Dolly’s sexual experience “refreshing rather than titillating or disgusting.” He appreciated her sense of humor, self-deprecation, vulnerability and curiosity. Dolly’s interest in his work and aspirations was genuine and wholehearted, and she relished the bohemian atmosphere of the studio John shared with friends.

Sloan knew his career as a fine artist would make supporting a family dubious at best. Neither wanted children. They believed Dolly was infertile until she got pregnant years later in New York, when Sloan performed an abortion on her, using instruments provided by a friend.

Both of Dolly’s alcoholic parents died by the time she was three. Caught shoplifting more than once, for a while she and her two sisters were living with an older brother, a devout Catholic and strict disciplinarian. Early in her teens, Dolly began drinking, a lifelong addiction which didn’t prevent many later, intermittent, successful endeavors: business manager of the Masses; secretary of Branch One of the Socialist Party (the “Silk Stocking” group with a large number of professionals), and fundraiser for various leftist causes.

Promoting a lecture by Eugene Debs in 1911, Dolly supervised ninety-odd volunteers. A “veteran of Carnegie Hall benefits,” she helped organize a rally there in 1916 on Emma Goldman’s release from prison for urging the dissemination of family planning information for anyone who wanted it. (Dolly’s picture was in the Times rather frequently those days, and she was often quoted.)

John’s sympathies were not with the anarchists (or communists), but both Sloans appreciated Goldman’s anti-capitalism and pacifism. Dolly “vehemently approved of Emma Goldman’s outspoken advocacy of birth control.” Attending her provocative lecture series on the topic, Dolly joined the Women’s Suffrage Committee of the Socialist Party, going to every branch and committee meeting , “and leapt at every chance” to distribute birth control tracts at major street rallies.

She was involved with the labor strike of the era, in the textile mills of Lawrence, Mass. Taken over by the Wobblies, and dramatized with mass picket lines, huge mass meetings, revolutionary songs, flying banners, nationwide publicity and appeals for support. To great media fanfare, Margaret Sanger led the children’s march out of Lawrence, placing them with willing families in the Northeast until the strike was over. (When this tactic was tried again in Lawrence, police and militia were called on to halt the exodus, entailing vicious beating of parents in front of their children at the railroad station.)

Dolly took charge of a contingent of boys and girls sent to Manhattan and Brooklyn, meeting them at Grand Central Station where police, journalists and political types singing the “Marseillaise” and waving red flags had created a scene of utter pandemonium. The train was late, the city permit to march the children to the relocation center hadn’t come. Sick children had to see doctors in local hospitals.

Although Dolly periodically disappeared to go on drunken binges, often involving other men, and possibly prostitution, sometimes bringing home venereal diseases, and John periodically suffered bouts of depression and despair, their marriage lasted 42 years until Dolly’s death in 1943 at age 66.

Toward the end, Dolly did have a major rival in a former student of Sloan’s, Helen Farr, who became his second wife when he was 72; she was 40 years younger. Wealthy, well-educated, Manhattan-bred, scheduled to go to Bryn Mawr, instead Helen decided to take up painting at the Art Students League. From age 16, she was totally enamored of John.

Once Helen and John began their affair, in strange ways Dolly came to rely on the younger woman. In 1935, when Dolly received a notice from NYU evicting all the tenants in their Washington Square apartment, as part of an expansion program, she asked Helen to stay with her until Sloan returned from Santa Fe. Despite offering to lecture at the university for free, the Sloans were evicted; their last residence was on the top floor of the famed Chelsea Hotel.

The next summer in Santa Fe, Sloan accidentally drove their car off an embankment and Dolly suffered a cracked vertebra. Listening to her “sob out her pain about their life and his relationship with Helen,” he finally acknowledged Dolly had known for a long time and was tormented by the truth. “With trepidation at the prospect of the loneliness he was consigning himself to, but with a strong feeling for what he owed Dolly,” Sloan promised to end the affair, and he did.

In 1938, John’s digestive problems had reached a crisis point, and he needed gall bladder surgery. “Feeling her usual panic,” Dolly asked Helen to come stay with her at the Chelsea. When Helen arrived, she got rid of the strychnine Dolly was hoarding and threatening to use. She stayed until Dolly seemed steadier, even enduring a visit from Sloan’s latest private student and model who made it clear she’d been more intimate with Sloan of late than either woman.

5

In 1916, Sloan’s part-time job at New York’s Art Students League turned full-time: its students generally technically competent, and knowledgeable about current trends. The school, founded in 1875, enjoyed a reputation as the place where a would-be artist could structure his own education, with no curriculum demands and complete freedom to choose courses.

But Sloan felt the student body was not always well served by those offerings. Artists such as Robert Henri, George Bellows, Guy Pene du Bois, Thomas Hart Benton, and Stuart Davis had been instructors, but in Sloan’s estimation most of the rest of the faculty was decidedly second-rate.

“Contrary to the long-established assumption that the realists of Sloan’s generation were to a man threatened and unnerved” by the Armory show of 1913, which introduced modernist European aesthetics in painting to the U.S. for the first time—Post-Impressionist, Cubist and Fauve art--Loughery asserts, Sloan, who was both represented in the show, and involved in hanging it, “knew that he was in the presence of something significant and challenging.”

When he began teaching, Sloan was ardently enthusiastic about the Old Masters as well as much of modernism. He wanted his students to see it all, to reject the narrowness of the academy which he himself had rejected: to ponder even the work he had trouble with at first, calling Cubism “the grammar of art,” which could only be beneficial for everyone to study.

Many students were motivated by Sloan’s passion, “almost maniacal fervor,” and rigor. The abstract expressionist painter, Adolph Gottlieb, a student in his teens, later declared Sloan’s wide range of interests was his finest contribution as a teacher.

In March, 1932, hearing George Grosz, one of the best graphic artists of Weimar Germany, was coming to the United States in the fall, Sloan told the League’s board of directors they desperately needed someone with Grosz’ strong academic background and modern vision as a satirist and cosmopolitan. Economic objections quickly sprung up, as well as uneasiness about hiring a foreign artist, when so many Americans were out of work—and a foreign Communist at that!

Grosz did end up teaching at the League in the ‘30s and intermittently till 1955: his collage techniques greatly influencing his student, Romare Bearden. But in the middle of a heated debate about hiring the emigre, Sloan called the League “a sinking ship,” resigned the presidency, and in high dudgeon, announced he would run for reelection the next month. “I’ll win it in a walk or not at all,” he declared publicly. And not at all, it was!

Believing students appreciated his flair, definiteness, clarity of principles, Sloan’s idea was to offer a compelling image of the artist which had nothing to do with the mundane business of making a living or pleasing a client. The great thing about embracing the calling of an artist, he told students, was freedom--from personal ambition, dictates of others, and just about everything that made life seem small and crass.

But as a teacher, he remained concerned with technique: the basic artists’ tools of solid draftsmanship, composition and color, the rudiments of anatomy and perspective. The compositional principles Sloan articulated whether in analyzing works of an Old Master, a contemporary talent or a student’s work in progress were constructive, without being either pedantic or formulaic, according to a student in one of his early classes.

However, by the time Sloan lost this election, he was viewed as cantankerous--too radical by many of the faculty, and old-fashioned by many of the students. Over the years, his take on modernism had hardened, being particularly dismissive of surrealism. Valuing human emotion and interaction as the center of painting, Sloan objected to the Post-Impressionists’ seeming “jarring indifference” to their subject matter.

In the last speech he ever gave at the League in a 1951 fundraiser, Sloan seeing himself as ”dusted off and dragged out of my ivory tower,” was determined to give his listeners a “good diatribe,” consisting of an unusually vitriolic attack on abstract expressionism.

The thing itself, he explained, wasn’t the problem: he’d seen some fine Pollocks and Gottliebs. “The nightmare,” Loughery writes, “was the generation of art students who were forsaking draftsmanship and the artists’ most important themes—human emotion and interaction—for the sake of paint-smearing and the cult of the new.”

6

The Society for Independent Artists had some trouble finding a venue in wartime New York for its 1918 show, but the 569 participants used several storefronts on 42nd Street. By 1919, and for the next ten years, the Independents would show at the Roof Garden of the Waldorf Astoria. The patronage of cosmopolitan New Yorkers generated abundant press coverage. Now painters and sculptors whose work had previously been seen only in the Village had an uptown audience of several thousand for a month out of every year.

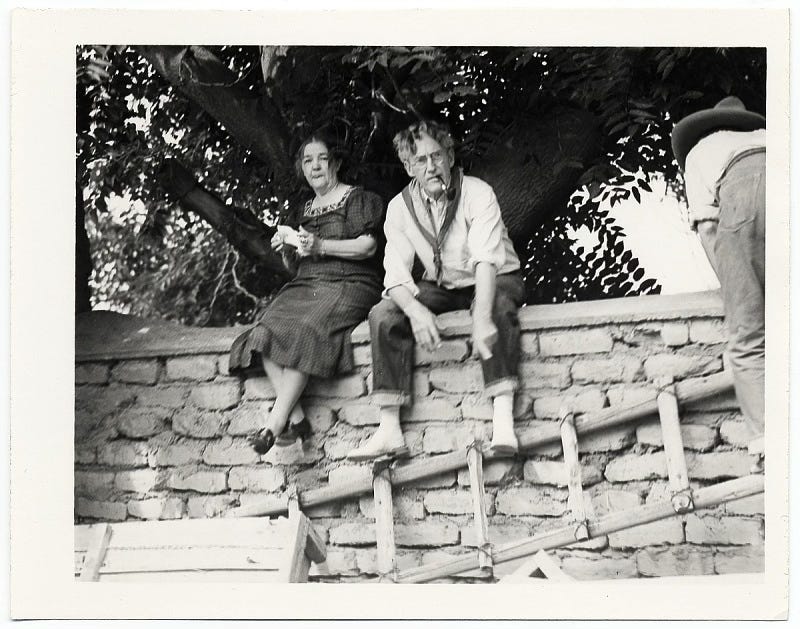

Despite criticisms that rank amateurs were displayed side by side with seasoned fine artists—anyone paying a nominal fee could enter—Sloan held firm and accomplished a great deal. In 1923, he invited Diego Rivera, David Alfaro Siqueiros, Jose Orozco, Rufino Tamayo and other Mexicans to exhibit their work. The 1933 show included six Native American murals (the Sloans had begun spending winters in the then-inexpensive Santa Fe area) and fifteen paintings by inmates of the Clinton Prison in New York.

Dolly Sloan was a significant force in the Society’s success, as fundraiser and organizer for their opening events. The Waldorf Astoria orchestra provided music one year, the Provincetown Players came to dance the next. At Dolly’s memorial, the chaplain at the Dannemora Prison, among others, remembered her as the woman who, since the Society first exhibited convicts’ work ten years earlier, had made sure art classes in the prison were kept properly supplied, especially when the state tried to cut the budget for such “inessentials.”

7

In 1912, several Socialist writers and graphic artists met to resuscitate the original, short-lived periodical, The Masses, which had gone bust, they felt, because it contained too much propaganda, not enough playful satire and graphic skill.

In REPUBLIC OF DREAMS: Greenwich Village, The American Bohemia 1910-1960, Ross Wetzsteon describes a typical revitalized 12 or 14 page issue which might include on-the-scene accounts of labor strife unreported in the mainstream press; articles on IWW efforts to organize the unemployed; exposes of manufacturers’ attempts to influence Congress; dispatches unavailable elsewhere on revolutions in Mexico, China, the Philippines. Essay subjects ranged from psychoanalysis to the link between capitalism and militarism, from birth control to prison reform, from free love to the Boy Scouts (who were being trained, the magazine asserted, to become soldiers).

MASSES’ writers debated the relative merits of direct versus political action, anarchism versus socialism, free verse versus meter. Editorials might touch on Margaret Sanger’s defense fund, the general strike in Belgium, the right to suicide, mutiny in the French army, organized charity, suffragists, the stock exchange, religious hymns, industrial sabotage, the Manufacturers Association, Fabianism, welfare. Even their advertisements captured the ethos of the era—Karl Marx five-cent cigars, birth control pamphlets, Jung’s books, Cubist prints.

Contributors included many of the leading poets, artists, writers and political theorists of the prewar and following decades—Sherwood Anderson, Upton Sinclair, Djuna Barnes, Vachel Lindsay, Amy Lowell, William Carlos Williams, Elizabeth Gurley Flynn, John Reed, Walter Lippmann, and from abroad, Maxim Gorky, and Bertrand Russell. However, the publication “remained actively hostile to the stirring of radical arts on the continent,” according to Wetzsteon.

Gertrude Stein was parodied; Proust, Joyce, Kafka and Eliot, all working at this time, were ignored. Although a Picasso drawing was published in an early issue, cubism tended to be seen in a “lighthearted but dismissive caricature.”

Sloan’s eclectic graphic contributions achieved considerable recognition. Particularly lauded for his cover after the Ludlow, Colorado massacre of striking miners, in what Loughery terms his “most dramatic and most effective image as a political artist.” Entitled “Caught Red Handed,” mine owner, John D. Rockefeller, is depicted as nervously attempting to wash the blood off his hands as the door to his hiding place is battered down. At his feet, his personally inscribed Bible lies open near a soiled towel.

Understandably proud of bringing in first rate artists to The Masses, Sloan also took great pleasure in working with fellow Village radicals on the 1913 Paterson strike pageant in Madison Square Garden, “throwing himself into the painting of the scenery, including a two-hundred foot backdrop of the mill.” John Reed coordinated the massive event (whose ultimate benefit to the workers was much debated), starting with 1500 strikers from the textile mills in Paterson, New Jersey crowding into ferries, then marching uptown singing the “Marseillaise” and the “Internationale.”

After a founding meeting, Max Eastman, disciple of John Dewey, was chosen as editor of The Masses. He received a congratulatory note from Sloan and the writer, Louis Untermeyer, which read in its entirety: “You are elected editor of The Masses. No pay.”

One historian described Eastman as the “John Barrymore of American radicalism.” A lean, blond Adonis, Max was a ladies’ man and an intellectual, having studied at Williams College and Columbia University (where he completed all requirements for a Ph.D. but refused to pay the $30 commencement fee). Max founded the Men’s League for Women’s Suffrage in 1909; his mother, a highly prominent minister, was asked to conduct the funeral of her friend, Mark Twain.

Max’s sister, Crystal, an anti-militarist socialist, was a leader of the suffrage movement, and co-founder and editor with her brother of a radical arts and political magazine, The Liberator. A graduate of Vassar and NYU law school (where she was second in her class), Crystal was co-founder of both the Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom, and the ACLU.

“No one was more aware than Eastman of the irony inherent in a ‘super-revolutionary magazine’ that lived as it was born on gifts solicited from individual members of the bourgeoisie,” the critic Rebecca Zurier points out. Author Floyd Dell called it “the skeleton in our proletarian revolutionary closet.” An early backer was Mrs. Alva Belmont, former wife of William Vanderbilt, an active suffragist who had led the “Mink Brigade” picket lines after the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire.

“A healthy lack of respect for the individuals and institutions most Americans held sacred had pushed the Masses into progressively more daring positions,” Loughery comments, “often with Max Eastman in the lead.” Editorials castigated the Associated Press for its failure to report on a coal miners’ strike in West Virginia: the news service’s own correspondent had served on the military tribunal which enforced martial law in the county during the strike.

Initiating a prolonged series of court battles in which people of the stature of Lincoln Steffens and Charlotte Perkins Gilman spoke up on behalf of the publication, only when AP management began to fear for its credibility were all charges dropped.

But with U.S. entry into WW1, the end was in sight. Although Eastman failed to get consent of the editors to sign a manifesto against American intervention when the artist George Bellows objected (soon afterwards, volunteering for the tank corps), the periodical continued bitterly attacking the war and condemning militarism.

Finally, the “government decided to curtail democracy in order to protect it,” as Wetzsteon remarks. The Espionage Act of 1917, along with the Alien Act, decimated the IWW and the American left, generally, resulting in many jail sentences and deportations.

At first, editors of the MASSES (whose readership had reached 40,000) failed to recognize the seriousness of the situation. In jest, circulating letters and postcards inviting each other to seditious meetings designed to overthrow the government. Three weeks later, The Masses received a letter from the postmaster of New York City, declaring the current issue “unmailable,” under the terms of the Act.

The editors won several court battles, but the magazine’s second class mailing privileges were revoked. Even Columbia University “mulishly” (as Loughery puts it) announced cancellation of their library subscription. Almost on the very day the staff closed up the office—giving away the furniture and selling the empty safe—they learned of the long-awaited Bolshevik revolution in Russia.

Forcing The Masses out of business didn’t prevent the government from charging them with conspiracy to obstruct enlistment. Despite representation by Morris Hilquist, an able lawyer and recent candidate for mayor on the Socialist Party ticket, popular sentiment was quite hostile to socialists and pacifists. And both the president and attorney general were known to be looking for a conviction which carried mandatory jail sentences. The trial was bizarre: “a scene,” Floyd Dell wrote, “out of Alice in Wonderland rewritten by Dostoevsky.”

Outside the courtroom a Liberty Bond drive was taking place. Every time the band struck up “The Star-Spangled Banner,” everyone in the court (led by one of the defendants) felt obliged to stand, until the judge finally called a halt to that putative display of patriotism. Some defendants had a hard time staying awake; Max Eastman did some serious “backpedaling under oath,” to insist The Masses was by no means an unpatriotic journal.

Dolly’s “pungent testimony confirmed absolutely the explanations by the defense,” Floyd Dell asserted. Apparently, hoping to use them as evidence of anti-governmental conspiracy, the D.A. had acquired the minutes of the 1916 meetings—possibly taken by Dolly herself—which had led to an artists’ strike. If there was one thing the leadership of The Masses had not been, Dolly clarified, it was a unified band of conspirators. Trouble was, they hadn’t been able to agree on anything. The fights, the jabs, the sarcasm! The jury deadlocked with eleven for conviction, one for acquittal. The defendants were freed.

Max Eastman subsequently went through numerous transitions. Visiting Russia in 1922, he extolled the virtues of Lenin, and befriended Trotsky who’d lived in New York for 3 months in 1917. One of the first Americans to perceive Stalin’s totalitarian tendencies, Eastman became Trotsky’s American translator, also arranging for the publication of “Lenin’s Testament,” warning the Bolsheviks against Stalin--damaging rather than enhancing Eastman’s own reputation among radicals.

A series of books written in the thirties and forties denouncing Stalin and Marxism made Eastman more of a pariah. When he became a “roving editor” of Reader’s Digest and a supporter of Joseph McCarthy in the 50s, he was dismissed, as Wetzsteon remarks, “as the kind of crank who saw Russian tanks on the border of Idaho.”

Sloan also saw the politics of the Kremlin as bankrupt. Supporting progressive presidential candidate Henry Wallace in the 1948 election, he viewed himself as occupying a sensible middle ground. But he’d served as Vice President of the Art Committee of the National Council on American-Soviet Friendship during the last year of the war, and had contributed some etchings to The New Masses, basically a CP organ.

In the heyday of the House Un-American Activities Committee, Sloan was ready to sign any petition against that “disgrace to the nation.” After two decades of keeping a resolutely nonpolitical profile he was again talked about in some circles as an unreformed “leftie,” or a “fellow traveler.” The FBI reactivated its file on the former Socialist Party activist, and Emma Goldman ally.

8

Leslie Fishbein’s Introduction to the lavishly illustrated, ART FOR THE MASSES; A Radical Magazine and Its Graphics, 1911-1917, cogently delves into the publication’s complicated, often disappointing, portrayal of African Americans--even though the editors generally “cherished and sought to preserve the integrity of ethnic cultures, espousing cultural pluralism long before it became fashionable.”

Blacks presented a special problem. The Socialist Party, hoping to achieve respectability, virtually ignored them; center and right-wing socialists sometimes acquiesced in segregation. Even Eugene Debs, the Party’s most popular leader, who refused to speak before segregated audiences in the South, failed to see any need for organized attention to the plight of blacks.

Dissatisfied socialists increasingly turned to the Industrial Workers of the World which attacked the racial policies of the American Federation of Labor, constituted almost exclusively by white men organized in skilled craft unions. While espousing egalitarianism, the AFL actively discriminated against black workers. Further, in 1901, they lobbied Congress to reauthorize the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, and began the first organized labor boycott: to discourage consumers from purchasing cigars rolled by Chinese workers.

In contrast, Fishbein writes, the new radicals in Greenwich Village appropriated blacks as a cultural symbol of paganism, free of the puritanical repression that plagued whites: wanting them to remain exotic and uncivilized, innocent of the corruptions of modernity. Blacks felt similarly constrained by white literary aspirations for them. Floyd Dell, for example, dubbed them instinctive poets—closer to nature than whites—yet demanded they be confined to dialect verse.

THE MASSES failed to sustain a coherent editorial policy regarding African Americans, Ms. Fishebin assesses. Portraits of blacks ranged widely from caricature to celebration. Dialect jokes and cartoons based on stereotypes (drinking and carousing men appearing idle, foppish, and dissolute) abounded.

On the other hand, the editors wished to support civil rights by portraying their subjects sympathetically. In support of the NAACP crusade against lynching in 1916, cartoons sharply attacked blacks’ victimization, likening lynching to the Crucifixion. As early as 1913, in response to a racial war in Georgia in which hundreds of blacks were driven from their homes, Max Eastman editorially urged them to arm themselves and retaliate.

Only gradually did THE MASSES abandon stereotypes and caricature for a more militant political approach, finally realizing the sense of desperation felt by blacks. Overall “the white radicals’ sophistication in racial matters came too late,” Fishbein comments. “Not until the Great Depression imposed the economic equality of poverty on blacks and whites alike did white radicalism acquire any lasting appeal for blacks.”

Much more progressive on women’s issues, the editors, having “great faith in women’s strength and in their right to full equality with men,” attacked sexual prudery, economic exploitation, social hypocrisy, and considered a wide range of issues: liberalized divorce, sexual liberation, birth control, economic equality, fashion reform. In traditional Marxist terms, some tended to assume “women’s economic freedom would lead to social revolution.”

Some cartoons echoed mainstream suffragists who invoked women’s innate moral superiority and their unique ability to apply lessons of domesticity to political life. It’s essential to realize, Ms. Fishbein writes, THE MASSES did not share the suffrage movement’s preoccupation with the ballot per se.

Floyd Dell, among others, was skeptical of the benefit to be derived from enfranchising women without an attendant alteration of consciousness. Emma Goldman hoped women would use the ballot to wrest control of their bodies away from men, to remove existing penalties against the spread of contraceptive information.

Nor did economic independence necessarily entail social freedom: career women still might remain enslaved to the tyranny of public opinion and to sexual repression imposed by the double standard. As long as the work available to ordinary women was alienating, Goldman argued, it might replicate domestic drudgery and provide no great advantage over it.

Emma Goldman was most acute in exposing the contradictions involved in the effects of sexual censorship. Reared as a sex commodity, in order to be guaranteed the safety and economic security of marriage, girls remained in total ignorance of the importance of sex. “Whether our reformers admit it or not, the economic and social inferiority of women is responsible for prostitution.”

Max Eastman criticized vice-commission reports which naively argued prostitution could be eliminated by the establishment of a national minimum wage for women. “This minimum wage…will give the moral people in the community a comfortable feeling that if any girl goes wrong it’s her own fault. She had the chance to get to heaven on a Minimum Wage and she went to hell on a toboggan.”

While some romanticized prostitution (viewing women as heroic victims) and celebrated any defiance of Victorian morality, the magazine was capable of striking a more positive note, emphasizing the spirit of freedom and joie de vivre of those “fallen women” who’d chosen their lot and derived personal satisfaction from it despite exploitation. John Sloan’s portrait of a prostitute in “The Women’s Night Court: Before Her Makers and Her Judge” contrasts the delicacy and refinement of that woman with the men indicted by the caption as responsible for both victimizing and judging her.

The historian Thomas J. Gilfoyle, author of a comprehensive study of prostitution in New York City between 1790 and 1920, described Sloan’s images as breaking new ground, “simply by minimizing and undercutting the immorality of prostitutes.” Instead of depicting her in a brothel or as an offering for the male consumer, “Sloan presented her as she presented herself in the neighborhood…in essence, an ordinary working woman…Sloan, in effect, erased the line separating ‘loose’ women from ‘good women.’”

9

Sloan’s career was strongly boosted when he and Henri first approached William Macbeth whose gallery was a stable, respected concern, to stage a group show (including some of their original Philadelphia circle) of what came to be called “The Eight.” The press hyped the show as a “secession” from the Academy, whereas the organizers took pains to clarify they didn’t see themselves as antagonistically replacing the Academy.

“The odd fact about this exhibition,” Loughery comments, “which swiftly assumed privileged status in American art history, was that the art works themselves were so varied, so dissimilar in theme and technique, that something for every possible taste might be found.”

What linked the artists was feeling smothered by a style of painting they didn’t approve of—from the genteel Boston crowd with their textbook-homey genre pictures to the over-elegant portraiture currently in vogue. In effect, the show was dedicated to the larger purpose of opening doors, clearing the air, endorsing pluralism seventy years before the word entered common currency.

Gallery shows and openings weren’t public events in 1908. Widely publicized and well attended, interest in “The Eight” hinted at the first stirrings of art as “chic,” rather than an institutional concern. Sloan organized the show’s traveling exhibition, which reached nine cities in the Midwest and East, in seven major museums, including the Chicago Art Institute, and two libraries.

His smartest move was to focus on cities considerably smaller than Chicago and Philadelphia. Art historian, Judith Zilczer, summarized: “In taking their art directly to the American public, The Eight demonstrated that cultural provincialism in the United States was less pervasive than contemporary and subsequent accounts of the period have inferred.”

The wealthy sculptress, Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney offered John Sloan his first one man show at her studio, leading to a respected New York gallery taking him on as a regular. Remaining a staunch supporter of Sloan’s work, Mrs. Whitney purchased some paintings, contributed to a fund which bought another to be donated to the Metropolitan Museum of Art, and financially supported many Society of Independent Artists annual shows.

The one man show emphasized what Sloan felt was his new strength: the radiant color of his summer paintings and portraits of the beaches and byways of Cape Ann. In 1914 and for a few more summers, the Sloans took a small, cozy house in Gloucester. Locals and visitors treated their cottage as an “open house,” with guests staying over, much drinking and occasional sundown to sunrise parties beginning with a clambake and ending with breakfast on the beach.

But that summer was also one of the most productive ten weeks of John’s life: completing 60 paintings, a figure equaling roughly one quarter of his total output since the 1890s. Working outdoors for the first time, Loughery describes Sloan’s desire to let color alone do the work of line, to break away from any strict adherence to the palette of nature--modifying his previous notions of craft and artistic purpose.

Henri had introduced Sloan to a “scheme of color”: a new set of pigments created by Hardesty Maratta, based on the primary, secondary and even tertiary hues of the spectrum providing 24 gradations (e.g. one moved from red to orange via red-red-orange, red-orange, and red-orange-orange). Grateful for an expanded palette that seemed more exact and consistent, Sloan’s paintings of the next few years achieved effects of color which the earlier city scenes didn’t even aspire to, Loughery remarks.

His Gloucester landscapes have an “unabashedly experimental, pell-mell, even rollicking air.” In some of these on-site landscapes, everything takes on the fluidity of the water and the sky. Rocks don’t look rock-hard, trees and hills don’t always have a believable weighted presence. Loughery sees elements of the “authentic van Gogh approach to the natural world that Sloan was working toward, with the energy of the brushstrokes themselves and the intensity or unreality of the color conveying a mood, an agitated alertness,” rather than documenting a scene.

The last summer the Sloans spent in Gloucester, 1918, the final year of the war, saw fear of espionage and resentment toward those who weren’t helping with the war effort reach its height--especially after the recent sinking of a tug and three barges off Cape Cod. Gloucester eagerly joined other communities in enforcing new ”anti-loafing” laws which called for the roundup and questioning (read: harassment) of any man between the ages of eighteen and fifty who wasn’t employed in the military. Police were instructed to comb the beaches and streets for “idlers” or “slackers,” and bring them to headquarters.

The Sloans switched to summers in Santa Fe: a roughhewn community of 8,000 permanent residents, with cheap rents, paintable landscapes and people, and pleasanter neighbors than one was likely to find in the east—the haute tourist qualities of present-day Santa Fe still in the far distant future. Yet the town had its own cosmopolitanism. Edgar Hewett, the founder of the New Mexico Museum, was a learned man with a wealth of knowledge about Native Americans.

Eager to see more artists of Sloan’s stature make the trip each year, Hewett ensured he was set up comfortably in his new studio. Sloan was deeply impressed by his initial exposure to those aspects of Pueblo culture which a visitor could know—the ritual dances, handicrafts, artwork (both ancient and contemporary).

His awakening to the profundity and dignity of the Native American experience took place just at the moment when its existence was particularly imperiled. Police harassment of the ceremonial dance was recorded in 1919 in the local papers, and the movement to ban Indian dancing in public continued to find a sympathetic audience. The characterization of these dances by the Commissioner of Indian Affairs as “useless and harmful performances” was racism pure and simple, Sloan felt.

Particularly infuriating were the coordinated attacks by the Bureau of Catholic Missions, and right wing Protestant groups like the Committee on Indian Affairs of the YWCA, working with members of Congress charging the Office of Indian Affairs with failure to assimilate the tribes and put an end to the “soft, nomad trades” of these backward peoples. Sloan and Henri joined in circulating an Artists’ and Writers’ Protest petition against the land-grabbing Bursum Bill, which the Secretary of the Interior was pushing, to facilitate the sale of pueblo lands to whites.

By degrees, Dolly and John came to see themselves as both New Yorkers and New Mexicans, the two identities often being equally satisfying. But Santa Fe was a mixed blessing for the couple, since Dolly was periodically binging on alcohol. At ease with both the locals and imported artists, she was a much loved figure since the late 1920s, as a principal organizer of the Hysterical parade: a kind of parody extravaganza staged each summer in comic tandem with the more traditional historical parade, a downtown celebration of the Spanish conquest of the area.

10

Especially after his Gloucester and Santa Fe paintings, John Sloan hated the “Ash Can” school label which had become attached to him and most of the members of The Eight: realist painters of urban scenes.

The realist slot in American cultural histories was used to categorize a group of artists, also writers—Stephen Crane, Dreiser, Frank Norris, Upton Sinclair—as “an accommodation that served mainly (and still does for some contemporary art writers) to devalue the painting,” Loughery claims. Adding, with the 1927 painting, The White Way, “in its spirit of unrelieved happiness…and with the ebullience of the painting, John Sloan put the dour ‘Ash Can’ label behind him again, just as a generation of scholars was about to embalm him in it.”

This biographer’s description of the painting is vivid. “Against an agitated sky of slate gray, pink, and violet, the view of the street…is chaotic and exciting rather than threatening. Grime is transfigured by snow and neon.” Several groups of people “go in search of a good time after dark through a wide corridor of shops, restaurants, and a theater that reduces the darkness to a backdrop.” Our eye is drawn “emphatically southward: Follow the trolley downtown, follow the pedestrians, follow the bend of the avenue, more pleasures await.” Urban life in the painting means “people coming together in varied combinations, a gaudy spectacle with rich, unforeseen possibilities…and promises of hidden joys.”

Mel Freilicher retired from some 4 decades of teaching in UCSD's Lit. Dept./ writing program. He was publisher and co-editor of Crawl Out Your Window magazine (1974-89), a journal of the experimental literature and visual arts of the San Diego/Tijuana region. He's been writing for quite some time. He is the author of The Unmaking of Americans: 7 Lives, Encyclopedia of Rebels, and American Cream, all on San Diego City Works Press.