By Mel Freilicher

Vulgar Favors: Andrew Cunanan, Gianni Versace, and the Largest Failed Manhunt in U.S. History by Maureen Orth on Delacorte Press, 1999

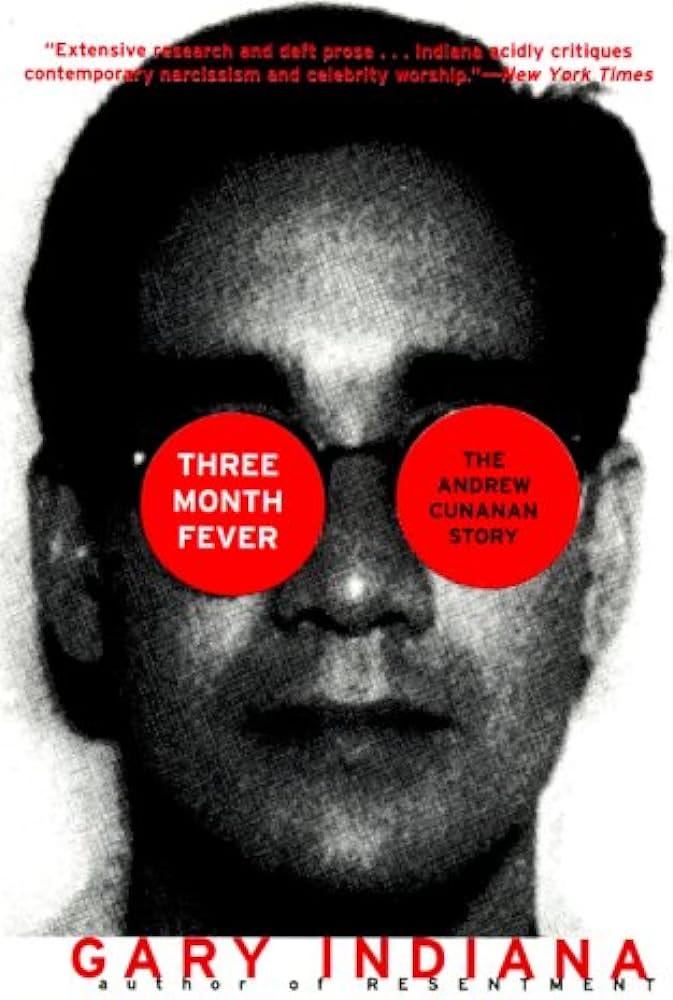

Three Month Fever: The Andrew Cunanan Story by Gary Indiana on Harper Collins, 1999

1

Three years after Andrew Cunanan’s death, I reviewed these two biographies for American Book Review. While I always chose books I admired to review, I proposed this piece because I needed to put in my two cents about why they were so truly trashy (more to come). Although I was satisfied with my comments on the writers’ opinions, writing and research, my own emotional responses to the content could only be implicit.

The whole Cunanan drama bowled me over: his killing five people—the grand finale being Gianna Versace—suggested a psychotic break, of course. But what about before that? I didn’t know Cunanan, but we lived in the same gay neighborhood in San Diego, and he was a history major at UCSD where I was teaching. Also, when the media started going wild, they called him a “chameleon,” frequently showing a kind of rogue’s gallery strip of 6 or 8 of his photos, with somewhat different visages.

Astonished, all these faces looked so familiar. I thought I must have slept with him, in the baths or something. Then I realized, it wasn’t that. We both regularly took the shuttle to and from the La Jolla campus to this neighborhood. I must have observed him, without knowing who he was.

It wasn’t just this kind of proximity which made Cunanan loom so large in my mental landscape. It’s that I had known quite a few gay and lesbian students at UCSD (and some at San Diego State); most of them, like myself and my friends before them, had gone through a certain amount of anguish to come out, then to keep on keepin’ on--even aside from the hellish AIDS epidemic.

At UCSD, I taught in the lit/writing major which was small: some students repeatedly took a variety of my fiction and non-fiction workshops, so I got to know them well. Their writing was often quite candid.

I remember one guy who couldn’t come out and was sobbing in my office. (I myself didn’t exactly come out in classes—though I did to him, naturally, and to others who needed to talk to me—nor was I exactly “in” either.) He dropped out of school, but when I heard from him years later, he appeared to be well-adjusted and happy.

One frequent pattern I saw with the males: mostly serious and excellent students until they hit the age where they could go to the gay bars. After that, some of them seemed dragged out at school, either tweaking or coming down from meth. Unsurprisingly, Andrew’s drug of choice—San Diego was the crystal capital of the universe for quite a while, and still seems to be a major epicenter.

I don’t mean to be blaming bar culture. Haven’t been inside a bar in many decades, but one in particular was lifesaving when I finally came out in grad school here. Jeff Weinstein and I would regularly go to the Barbary Coast together: a hang-out near the airport, chiefly for black sailors and their posse, hippies, students (always some females there, including our friends) and counter-culture types. The dancing was intense; the whole experience exhilarating, tribal, without posturing (and for us, anyway, without drugs, except pot).

But the majority of gay men I’ve known—whatever generation—have had a drug and/or alcohol history: quite a few, including acquaintances and close friends, went down the tubes completely. A number of friends did save themselves, mostly through 12 step programs. (I never went that route with my own cocaine addiction, which happened later, still a long time ago. I was able to stop completely—but more than a year after I knew I needed to.)

Heartbreaking to watch some of the younger guys I used to go out with get totally strung out on meth. Despite the existence of some quality gay rehab centers here, and literally hundreds of 12 step meetings daily all over the county, sadly for most, it seemed like there was no way back.

The causes of drug use are many and more or less obvious, especially for any group of people who already have a strike or two against them to start with. Certainly, growing up, most gay people, even post-Stonewall, are aware of virulent obstacles, even if their families are accepting--or sympathetic, even rarer. Of course, for the poor, especially non-whites, just existing within the racist crap of this class-stratified society must be utterly strenuous.

Questions about why some people can get it together and others can’t are unanswerable: though looking at individual stories can be instructive—or, less often, titillating. In NA, they talk about hitting bottom first--busted and/or jail. Without something you love more than getting high, it’s mystifying to me what motivates people to stop. I myself had a lot to lose—teaching jobs I liked, a strong desire to keep writing, a lively social life, a devoted partner.

Cunanan’s background is one of the thorniest: a fact which his biographer. Maureen Orth, seemed able to report on with some accuracy, but with zero ability to empathize, or comprehend the consequences of how deeply damaged he was. And, poignantly from my perspective, both biographers appeared to have no regard for how much Cunanan attempted to create a satisfactory life for himself, before what must have been the psychotic break.

For an exhausting period of nearly 4 years, Andrew lived with his mentally unbalanced mother in a small, two bedroom apartment: she chain-smoked, talked incessantly, and threatened suicide. (Orth describes her as “both needy and smothering.”) Even before his father deserted the family, she used to call Andrew her “marriage counselor.” Neighbor Hal Melowitz, a psychiatric social worker, was quoted: “You’d need a crowbar to pry her away from her son.”

During this same period, he was working part time at Thrifty’s drug store, attending UCSD full-time in two stretches, doing volunteer work with the AIDS Foundation (years before life-saving antiretrovirals were available).

The disappearance of his father, Modesto “Pete” Cunanan, after Andrew’s first year at college (he got a scholarship to return to school) made life deeply problematic. Pete had retired from a career in the Navy, earned two business degrees, and moved the family from a lower/middle class suburb to Bonita, an upper class one.

During the nine years he worked as a licensed stockbroker, Pete was employed by six different brokerage firms; never staying at one for more than two years. Fired from several agencies, Pete came under suspicion of embezzlement, fled the country for good, then became a member of Clare Prophet’s cult.

When his father was in the money, they sent Andrew in eighth grade to one of the most exclusive private schools in the area, the Bishop’s School in La Jolla. His classmates’ families were incredibly wealthy. When Pete went back to the Philippines—Andrew had never told anyone he was bi-racial—suddenly, vertiginously, no longer even a nominal member of this social class, Orth remarks Andrew “slavishly lusted for the material goods of his privileged classmates.”

Although these facts come from Maureen Orth’s horrible book, she totally ignores their import in her tendentious, essentialist effort to paint Andrew, as she writes in her prologue, as a “narcissistic nightmare of vainglorious self-absorption.” There, she claims to be “saddened to see how drugs and illicit sex increasingly coarsened his instincts, how prostitution on many levels eventually left him lazy and unprepared.” (Saddened, indeed!)

About the prostitution, Orth describes Andrew as the “Dolly Levy of Hillcrest.” That is to say, he introduced young men to older gays (not for pay), especially closeted Republicans. For some time, he himself had a sugar daddy (“like a geisha,” Orth remarks) who took him to Europe.

A scene you could find in any gay community at this time, and presumably virtually every hetero one as well, which included young people with uncertain futures—especially before computer and smart phone hook-ups made such an intermediary unnecessary. (Silverdaddies.com, anyone?)

Some of Orth’s examples are particularly absurd. For instance, she argues Andrew refused to work to help pay for the Bishop’s School, which doubtless would have been both a token gesture, and completely set him apart from his classmates. Nor is it at all clear Andrew had any awareness whatsoever of his father’s precarious financial position, shady dealings, or any premonition of being abandoned by him.

In that same preface, Orth establishes her Sodom-and-Gomorrah-cum-California stereotypes, remarking Andrew had been “seduced himself by a greedy, callous and pornographic world that proffered the superficial values of youth, beauty, and money.” The book repeatedly depicts a “lazy materialist,” hopelessly entangled in status and unmanageable struggles within a debauched gay community. Any desperately needed discussion is forestalled by invoking a diagnosis of “classic narcissism”: more or less a defining symptom of every affective disorder ever conceived.

Orth makes much of the fact that meeting gay men at the bars, Andrew lied about his background, mostly painting himself as richer, older and more experienced—as if this was unique behavior--meanwhile cheerily cataloging his burgeoning obsession with crystal meth. Tagging him as an “habitual closet user and dealer” (which may have only meant he supplied it to his peer group—a common strategy of users, to cut their own costs.)

Despite the manifest delusionary, paranoid and just plain crazy thinking endemic to crystal meth users, Orth continues to pile on many examples of Cunanan’s “pathological lying” about his origins and famous friends. This, too, despite her report that Andrew’s average endowment and avoidance of the gym eliminated his chances of being a high-priced rent boy: forcing him to rely on his wits and personal charms.

Her depiction of Hillcrest borders on the hysterical (in all senses of that word). For one, she focuses on sensationalistic details about a bizarre acquaintance who played a minimal role in Andrew’s life, a “pornography purveyor,” and crystal meth dealer who stole a million dollar Barbie doll collection from his ex-lover then burned down his house.

She devotes almost an entire chapter to Vance Coukoulis, son of a retired Air Force general, allegedly “the most notorious party giver in Hillcrest—the ringmaster of the Evil Circus…a diminutive ex-seminarian, half-Irish, half Greek.” With no evidence, she claims, “Andrew desperately tried to keep up with him.” Coukoulis spent some time in jail before he returned to Hillcrest, and it’s not clear if Andrew even knew him at that point.

However, “Vance’s dungeon was notorious in Hillcrest”—where was I?—“a must-see venue for a social animal like Andrew.” She goes on to assert, “In a place like San Diego,”(now, is that Sodom or Gomorrah?) “it was inevitable that Vance and Andrew would meet and conspire—they often favored the same quarry.” (Perhaps they went quail hunting with Dick Cheney and Co.!) Many kooky Coukoulis tales accrue concerning charges of sexual exploitation of minors, the Pope, Chernobyl, and counter-spying for the CIA and the Chinese.

Citing interviews with some alleged friends of Andrew’s, Orth claims he was “cheap entertainment” for them. Absurdly, she takes them to task for not displaying appropriate moral indignation at his crystal use—despite whatever these individuals’ own roles may have been in what she repeatedly describes as the community’s drug-saturated lifestyle.

Significantly, Orth neglects to interview key individuals who might actually have shed some light on Andrew’s own options and choices. Notably, roommates, bartenders, part-time students and hustlers, all coping with similar difficult familial, economic and social exigencies.

Orth goes into great detail about Cunanan’s murder victims to which the media applied the odd term “spree killer” (distinguished from serial killing): nomenclature seeming to imply giddy glee. The murders have been gone over ad nauseam in various biopics and mini-series (which I’ve mostly avoided), chiefly focusing in Versace: anyone interested in such details will have an easy time accessing them.

About Cunanan’s first murder, Orth clearly seems to share Andrew’s predilection for clean-cut Midwesterners like Jeff Trail and his partner, David Madsen (the second victim). “Although Andrew was a practiced phony,” she comments, “he knew the genuine article when he saw it.” Trail, a graduate of Annapolis, was a “handsome, authentic all-American,” and Orth asserts he, “personified the solid ideals of the land he sprang from.” (Ugh.)

The second half of the book is less vicious: detailing the unfolding evidence against Cunanan, the inept, cross-country manhunts, and the murky jurisdictional issues they brought to light. The writing there is marred by a falsely modest, self-congratulatory tone when reporting her own contributions to unearthing new evidence (rather, evidence lying there unnoticed), and her inadvertent assistance to the Versace family in precipitously shutting down the Miami investigation, so Gianna’s HIV+ status wouldn’t be exposed.

It’s disheartening and tedious to revisit this author’s complete lack of understanding or empathy. Personal preference, and/or encouragement by her editors, looking for sensationalistic melee—who cares? Her contempt is palpable, and clearly symptomatic of the larger sociological problems gay people face. That Orth can’t see Andrew Cunanan as an actual person is not surprising.

But Vulgar Favors’ fatal failure is the total absence of any pertinent analysis concerning the consequences of homophobia, for instance, the politics of our sinister, often engineered, drug epidemics, or the chronic media fetishizing of youth and power. In her need to paint his entire milieu in broad and stereotyped strokes, the book’s only value seems to be in providing some useful details for others with a surer hand, actual class consciousness, and far better intentions, to interpret.

2

Gary Indiana, often a fine writer and savvy social critic, doesn’t do much better in the case of Cunanan. Since Three Month Fever isn’t a biography, it provides considerably less information than Orth’s book, especially concerning Andrew’s childhood. Indiana’s preface is as revelatory as Orth’s, and in some ways similar. He seems to share much of the contempt she displays, believing the people he interviewed are completely unreliable. ”I did not reckon on the extreme difficulty of getting anyone involved with Cunanan to talk.”

Claiming to have “encountered a kind of phobia—laden mendacity among potential informants,” he suggests Cunanan may have simply had “ghastly taste in picking friends; at any rate, some made it plain that whatever tidbits they had were only available for great sums of cash.” Besides, Indiana argues the media had already totally obfuscated everything: “egregiously, with little or no regard for accuracy, Cunanan’s life was transformed…into a narrative overripe with tabloid evil.”

Both writers excoriate the media and many individuals’ greed, but neither one addresses the question of why others—particularly their interviewees, let alone readers—should perceive them (writers from the east, unfamiliar with the scenes they’re describing) any differently.

While Indiana’s preface sensibly concludes a search for the truth “is somewhat close to folly,” it also asserts, “It was clearly necessary to simulate Cunanan’s mental state throughout the narrative”: a “necessity” which seems to have disallowed work more suitable to Indiana’s considerable talents, such as close scrutiny into media techniques of distortion and dismissal. One wonders if his and Orth’s editors went to the same book-as-tabloid management schools.

In any case, Indiana declares it was “crucial to speculate about many quiddities of Cunanan’s psyche and solitary behavior [differing from Orth’s depiction of the “social animal”]—I wanted above all to make this person palpable to the reader as a person.” He readily admits he didn’t know how Cunanan felt: for example, if he had “the standard male tooth-less castration dreams [?!] when he left Norman Blanchford. But I feel that he did.”

Such ersatz empathy appears to be the guiding principle for Indiana’s going into and out of Cunanan’s consciousness, often at the most difficult, nuanced, and inaccessible junctures of his life: how Andrew’s need to impress the idealized David Madson dovetailed into their sliding thresholds of S&M play; complex adolescent reactions to his father’s financial collapse; flashing panic about kept-boy Andrew’s ever-thickening waistline.

Highly conjectural, often unconvincing, these intermittent first-person stream-of-consciousness sections (in addition to some from the victims’ perspectives) appear to function mainly to exhibit the writer’s own rhetorical flourishes.

Constructed as a pastiche, interestingly, Indiana weaves in fragments of Andrew’s own writing, mostly from letters and postcards as well as documents from his life: autopsy reports, his admission essay to the Bishop’s School, their letter of support for his college applications, and records of FBI interviews.

Like Orth, Indiana indulges in sensationalism. In fact one of the most vivid parts of the book, when Andrew visits his first victim, the wholesome Jeff Trail, is also the most sensational. Indiana sketches ultra-prosaic dinner table chit-chat, barely masking Andrew’s homicidal, masturbatory fantasies. (Somewhat inexplicably, he sees Cunanan as originally bringing a gun with him to Minneapolis to commit suicide.)

The author creeps into Andrew’s mind: The feeling that “it was coming closer, something awful was coming closer,” finally explodes into a graphic scene of Cunanan using a claw hammer to crack open Jeff Trail’s skull, then trying to gouge out both his eyes. “Gouts of brain the consistency of custard clung to the hammer-head and dropped off it. Andrew flicked blobs of it off his arms. Each time the head struck the hardwood it sent a loud thunk through the walls…As life drained away Jeff twitched like an appliance shuddering to a halt. His throat made a harsh clawing noise, Andrew attacked the skull as if driving nails through it.”

Quite possibly Andrew was driven by uncontrollable rage (and masturbatory fantasies); possibly he was partly, or more, disassociated, at some remove from the horrors of what he was doing. In any case, this writing reads like reportage from a deeply grisly situation where Indiana was eminently not present.

Indiana is witty about the vapid social scenes in which Andrew and his sugar daddy, Norman Blanchford, moved among different affluent “Republican queens” in Scottsdale, La Jolla and Europe. Somewhat less so about “the braindead flavor of the ambience” in San Francisco, which he sees as instrumental in David Madson’s initially finding Andrew so attractive. But these attitudes also appear to make such scenes somewhat opaque to Indiana.

Certainly, there are moments of keen insight which we’ve come to expect from this writer, who is gay himself. Discussing why the establishment misunderstood clean-cut Jeff Trail’s and Madson’s attraction to Andrew’s drug use: “Homosexuals are, in American society, widely consigned to the same category of things as drugs, the category of illicit dirty things that people have to be protected from, and any homosexual however law-abiding, and even puritanical…is trained from an early age to distinguish hysteria about sex from the realities of sex and hysteria from reality about drugs.” His conclusion: Cunanan’s drug use probably “would lend a touch of sexy danger to an already fraying romance.”

Indiana invites harsh criticism—or at least holds himself to the highest standards—when his preface declares, “I would like to dissolve these unsatisfying modes,” speaking of the “’nonfiction novel’ a la Capote or Mailer.” But Three Month Fever is in no way comparable to Capote’s In Cold Blood which remains a stellar landmark of twentieth-century American writing.

This author does invoke a pedigree for his own work, notably including James Baldwin’s excellent, The Evidence of Things Not Seen, another high point of contemporary non-fiction literature, and virtually the antithesis of Indiana’s book. In reporting on the trial of the alleged Atlanta child murderer, Baldwin was exquisitely aware of context.

He thoroughly examines the backgrounds, psychological and sociological assumptions of every participant (almost all of them African American), including himself—lawyers, judges, family members of the slain children, the rather hapless defendant, who clearly didn’t commit the vast majority of at least 28 murders done between 1979 and 1981.

Although Wayne Williams was only accused of the last two murders, there appeared to be a general consensus: somehow the conviction would close the book on this situation, and reinvigorate Atlanta’s faltering tourism business.

Central to Baldwin’s study is his discussion of the “moral vacuum” which has always been at the heart of black/white relations in this country, rendering practically all contemporary dialog largely an exercise in bad faith; his resultant writing style is extremely tentative and tenuous.

It may well be Baldwin’s anthropological approach, which takes absolutely nothing for granted, would serve Cunanan’s catastrophic story best. That the requisite compassion, lucidity, and sensitivity to translational complexities would most likely be found in an expatriate like Baldwin—having lived in Paris for years before returning to Atlanta to write this piece, originally for Playboy: someone intimately familiar with our hyper-racist culture from which he had also been mercifully removed for years.

In this case, there is so much to wish to be removed from: fierce economic constraints on the internally chaotic nuclear family, as well as on So-Cal’s fast lane, burnout druggie lifestyles, and, more generally, the whole set of solipsistic, insensate, greedy and violent imperatives saturating our blighted society, then and now.

Mel Freilicher retired from some 4 decades of teaching in UCSD's Lit. Dept./ writing program. He was publisher and co-editor of Crawl Out Your Window magazine (1974-89), a journal of the experimental literature and visual arts of the San Diego/Tijuana region. He's been writing for quite some time. He is the author of The Unmaking of Americans: 7 Lives, Encyclopedia of Rebels, and American Cream, all on San Diego City Works Press.