By Fred Glass

In the 19th century, it was common for American workers to labor for 10 or more hours a day, six or even seven days a week. The struggle for the eight-hour day began in earnest in the 1860s, slowly winning the goal workplace by workplace, state by state, but always prone to reversal during economic depressions. Employers were dead set against it, claiming, as they continue to do today whenever workers call for a better deal, that should it prevail, it would be the permanent ruin of business, and all the jobs will disappear. Instead of the eight-hour day, in the words of railroad baron George Baer:

“The rights of the laboring man will be protected, and cared for, not by the labor agitator, but by the Christian men to whom God has given control of the property interests in this country.”

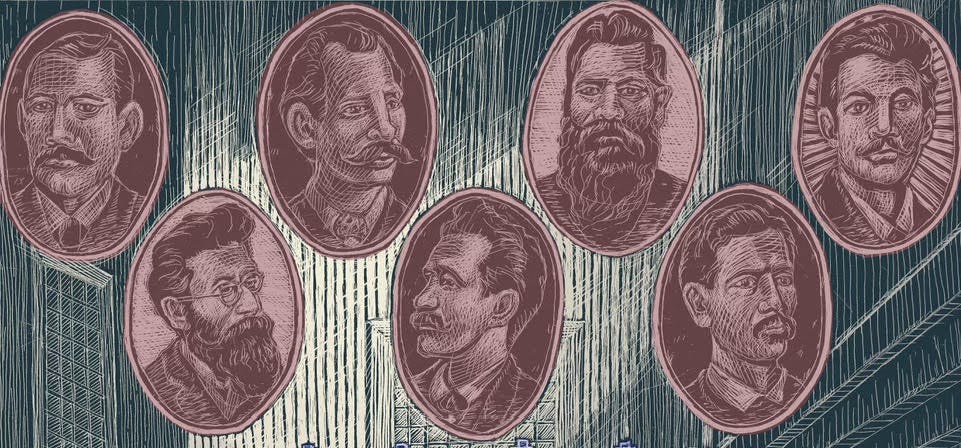

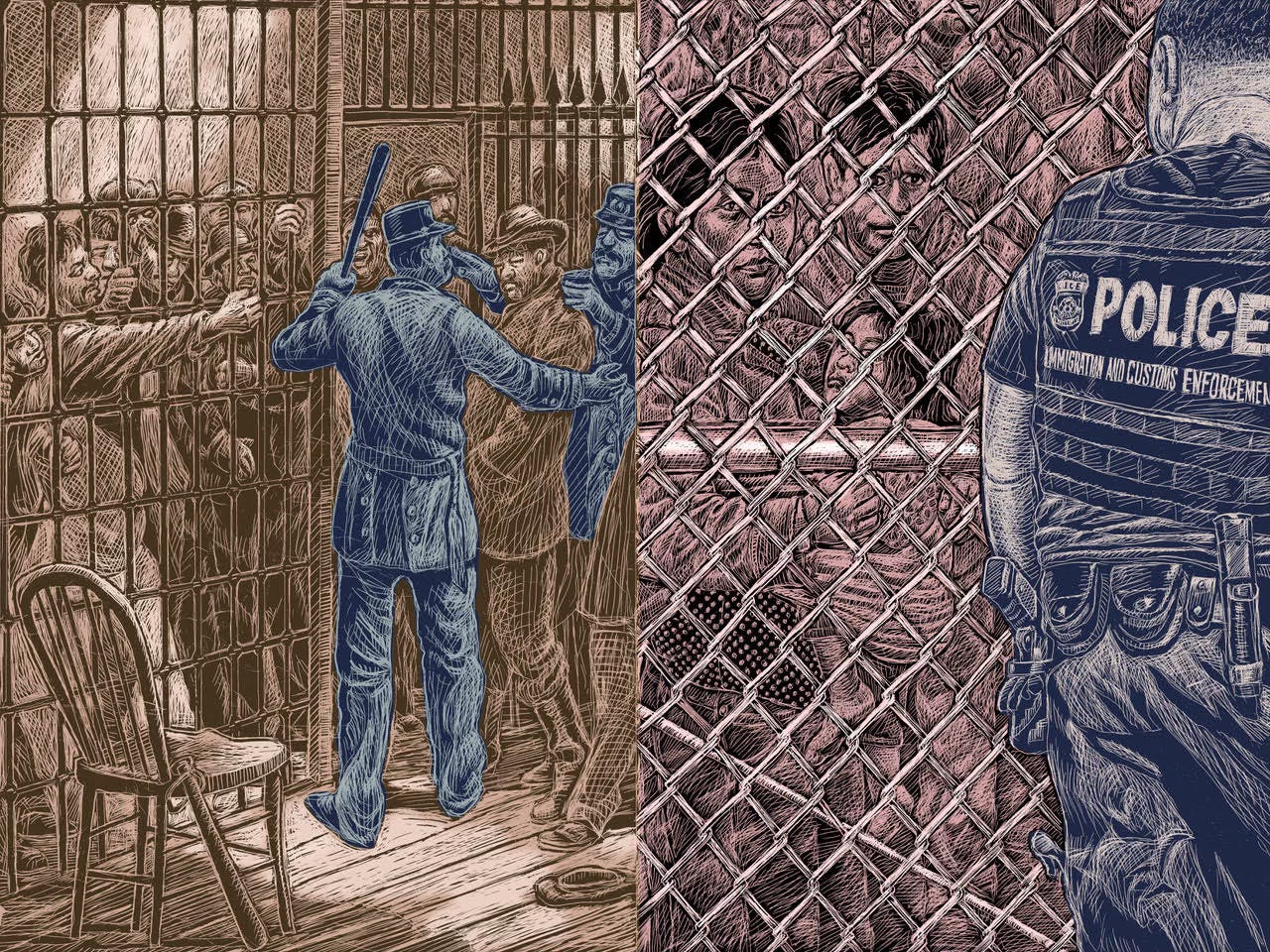

The battle for the eight-hour day built to a call for a general strike on May 1, 1886 answered by a third of a million workers across the country. But after the infamous events in Haymarket Square in Chicago — involving a bomb, an unknown perpetrator, and a police riot — the city’s employers and government unleashed a red scare, targeting the most effective immigrant worker organizers. It ended in the kangaroo court conviction and hanging of four men and continued imprisonment of three others. Illinois governor John Peter Altgeld, after examining the matter, pardoned and freed the prisoners, declaring their trial a miscarriage of justice.

The Haymarket martyrs’ cause was taken up by the newly formed Socialist International, which among its first orders of business designated May Day as a day of remembrance and called for its establishment as a workers’ holiday the world over. In one country after another, workers’ movements pushed employers and governments to recognize May 1 as a paid holiday and to establish the eight-hour workday as the standard. At times, the May 1 movement was met with bloody repression. In some places, it took a general strike to win the holiday and the eight-hour workday.

In the US, Labor Day in September was viewed as a safe alternative, a non-radical day of rest for workers, untainted with association with anarchism, socialism, and the Haymarket bombing. It took another half-century before the eight-hour day was made the standard workday in the United States with passage of the Fair Labor Standards Act in 1938.

Today, International Workers Day, or Labor Day as it is simply called in many places, is celebrated in close to 100 countries. Despite May Day’s lack of official recognition in the United States, the idea has been making a surprising comeback against traditional Cold War–era disapproval over the past few years. As a new generation becomes radicalized by the continuing failure of neoliberal capitalism to offer a viable future, perhaps the egalitarian ideas behind May Day will resonate with young people fighting against systemic racism, economic inequality and climate change, and for a better world.

Fred Glass is the author of From Mission to Microchip: A History of the California Labor Movement (UC Press, 2016) and a member of the State Committee of California DSA