What do D.H. Lawrence, James Joyce, Margaret Sanger, and Geoffrey Chaucer have in common? HINT: it has to do with S E X.

The answer? All were caught up by the Comstock Act—the same set of zombie laws that antiabortion forces are trying to reanimate right now to try to make one of the medications used in abortion, mifepristone, illegal, and thus, effectively, outlawed.

The Comstock laws prohibited anything sexual from being sent through the mail—thus “lewd” books and contraception became unhappy bedmates in its enforcement. As a March 2017 issue of Granta notes:

On 3 March 1873, the Comstock Act was passed by the United States Congress, making it illegal to send any ‘obscene, lewd, or lascivious’ books through the mail. The law was used to suppress birth control and abortions, but also led to the banning of classics such as Chaucer’s The Canterbury Tales, Boccaccio’s The Decameron and, later, to persecute modern authors like Ernest Hemingway, John Steinbeck, William Faulkner and F. Scott Fitzgerald.

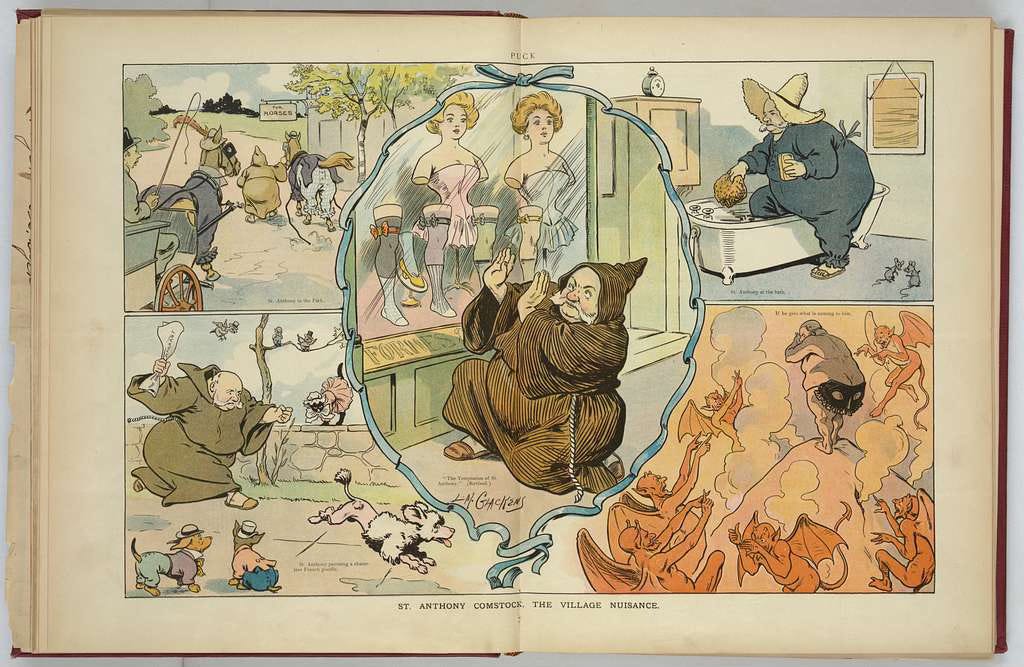

The man behind the law, the eponymous Anthony Comstock, considered himself a ‘weeder in God’s garden’, and was behind a number of placard-appropriate catchphrases used to rouse support for his Victorian moralising. His best are probably, ‘Morals, not Art and Literature!’ and ‘Books are feeders for brothels!’

Comstock’s extreme prudery dated from his experiences in the Union army during the Civil War where not only did he have to watch his fellow soldiers get drunk (the horror!) but see them read sexually explicit dime novels that were widely available through the mail. Later, he joined forces with elites through the YMCA to try to ban everything from saloons, nude paintings, and naughty books to birth control, abortions, and women’s health pamphlets.

He was never elected to public office but was appointed a postal inspector, which gave him great powers to enforce the law that was named after him, but which he didn’t actually write. To say Comstock was obsessed with eradicating sex is an understatement. And while much of his laws were eventually deemed unconstitutional, they weren’t wiped off the books, so like zombies, they are being revived by the Right to go after sex and women’s reproductive autonomy yet again.

In Intimate Maters: A History of Sexuality in America, John D’Emilio and Estelle B. Freedman outline the profoundly shifting sexual mores throughout the span of the U.S. Of particular note to them are the moments when changes regarding sexual attitudes were happening at a rapid clip.

The mid-to-late 19th century was just such a time. The Industrial Revolution brought more and more people from rural areas into cities and factory work. Immigration from all over Europe was beginning to surge. And post-slavery, many Black people migrated north to find employment. Such profound changes to the ethnic, racial, and class make-up of the country sparked concerns about chaos and how to control it.

This was also a period where women were more frequently in the public sphere via advocacy for suffrage, but also working to mandate temperance to curb what they saw as rampant alcoholism and its terrible impact on Christian families and wives. Thus women were taking on more political roles in their advocacy work—even if that work upheld a conservative Christian moral order aimed at keeping women moral, pure, and in the home.

Add to this the promulgation of more and more commercial representations of sexuality in the form of pulp and dime novels for adults that could be mailed to homes, the growth of prostitution, and the advent of contraception, which working and middle-class women embraced in order to be able to plan their families and limit their pregnancies.

As D’Emilio and Freedman note, all of this provoked a panicked response from moral reformers who sought to contain the vice they saw around them. And yet, this produced some interesting consequences. D’Emilio and Freedman observe:

Such organized efforts to reform sexual practices represented yet another expansion of sexuality beyond the family, into the world of politics. The increased visibility of sexuality in the public sphere disturbed middle-class Americans, especially middle-class women, who had been entrusted with the guardianship of the nation’s morals. In response to the movement of sexuality outside the family, these women sought to retain their authority over sexuality by organizing moral reform and social purity crusades. In the process, women themselves contributed to the expansion of sexuality into the public arena. As they left the hallowed domestic sphere, women increasingly perceived sexuality as a political, and not simply a private, issue.

Hence, to see women as simple victims of an oppressive patriarchal order misses the complexity of its construction. Women were active participants in both the restrictive sexual codes governing them as well as in their dismantling.

Anthony Comstock, then, and his prurient and obsessive crusade against vice and “lewdness,” was able to get his federal anti-obscenity law passed unanimously in 1873 because the public was primed to support his efforts—he “could not have managed his campaign without broader public support,” as D’Emilio and Freedman point out.

Furthermore, they observe:

Two underlying themes characterized the anti-vice efforts to use the state to regulate sexual expression. First, sexuality had to be restored to the private sphere; therefore, any public expression of sexuality was considered, by definition, obscene. Second, lust was in itself dangerous; therefore Comstock and his allies attacked not only sexual literature sold for profit but any dissenting medical or philosophical opinion that supported the belief that sexuality had other than reproductive purposes. Thus, even doctors paid heavy fines for publishing discussions of contraception or sex education.

The point here is that sex itself is suspect. Its only raison d’etre is for procreation: anything else is wrong, dangerous, obscene, and sinful.

And here we get to the crux of our current dilemma. The conservative Christian movement behind antiabortion (and increasingly anti-contraception) efforts is actually also anti-SEX and thus, by virtue of association, ultimately, anti-woman.

The leap from banning abortion to banning contraception emanates from a profound backlash to not just feminism and sexual liberation but to the 20th and 21st centuries, period. As happened in the 19th century, the moral panic over sex is a stand-in for fears concerning massive and rapid change.

The current changes—from AI, Instagram, and Pornhub to climate catastrophes, refugees at the border, war, and a besieged democracy—are real and profound. They’re similarly destabilizing as were the rapid transformations in the 19th century to people then.

So, the problem with powerful figures like Supreme Court justices Samuel Alito and Clarence Thomas, and their willingness to revivify the Comstock laws, isn’t just that they’re patriarchal; they’re anti-sex and anti-pleasure in an era when we actually desperately need real connection and joy.

We’ve got to see all of this for what it is so that we can combat it effectively for theirs is a cold, oppressive, and joyless world order. And history has shown us, it’s not the answer to what ails us.