Open Shop II: Union Organizing Campaigns

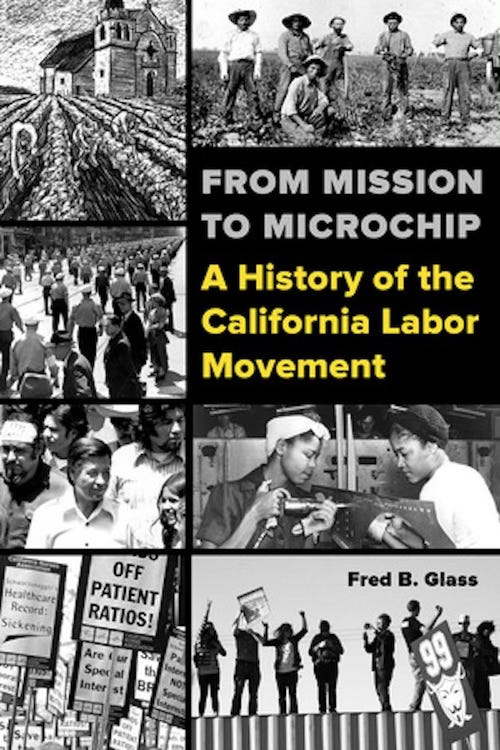

The Labor History Corner--an excerpt from From Mission to Microchip: A History of the California Labor Movement By Fred Glass

A version of this article appeared on the California Labor Federation California Labor History website. You can buy From Mission to Microchip: A History of the California Labor Movement from the University of California Press.

A rapidly growing Los Angeles economy and a population that leaped from one hundred thousand to a third of a million between 1900 and 1910 demanded new buildings, new services and more workers to provide them. Despite the prevailing official optimism about life in sunny southern California, many recently arrived working people found themselves living and toiling in unexpectedly difficult circumstances. When union organizers went looking for workers to sign up, it wasn’t hard to find them, even within the city’s repressive open shop atmosphere.

The Los Angeles Council of Labor authorized two dedicated and capable leaders, Fred Wheeler and Lemuel Biddle, to devote their time and energy to help workers who wanted a union. The California State Labor Federation, formed in 1901, hired Wheeler as its state organizer in 1903, and secured financial assistance from the national American Federation of Labor to help pay for Wheeler and Biddle’s work. Biddle served as AFL district organizer from 1901 to 1907. These two organizers were personally responsible for increasing the number of unions affiliated with the council from 26 to 64 in a few years—and that represented just part of the movement’s growth. Between 1900 and 1904 Los Angeles union membership more than quadrupled.

Organizing El Traque

Born in Philadelphia and trained as a machinist and shoemaker, Lem Biddle passed through many other jobs, several unions and a number of states before arriving in Los Angeles in 1888 at the age of forty-two. Biddle had been blacklisted by the railroad companies for his role in the Pullman strike in 1894. So he was no stranger to organizing when he accepted the challenge of assisting Mexican railway workers form a union.

In April 1903, at the same time as Wheeler was helping organize Japanese and Mexican beet workers sixty miles north in Oxnard, Biddle was asked to help workers on the Main Street line of el traque. Main Street was a center of commerce and industry. But the track workers, who made fifteen cents an hour, had little opportunity to either shop or work in the businesses on either side of the ditches they were digging.

Biddle quickly enrolled several hundred in a newly chartered AFL federal union local. (Federal unions were offered by the AFL to groups of workers without a natural fit with an already existing national union. They were also designed as a way of giving minority workers a union when the appropriate local refused to take them in.) With a workers’ committee, Biddle approached a Pacific Electric Railway manager, who initially agreed to increase wages to twenty cents an hour for day work, thirty cents at night, and forty cents on Sundays.

Pacific Electric owner Huntington reversed the decision, and several hundred workers walked off the job. Within a week, their numbers had grown to fourteen hundred. They received financial support from the Socialist Party and the Labor Council, and other workers joined them in solidarity on the picket lines. But Huntington was ready.

He paid to import an enormous number of African-American workers—by some accounts, nearly doubling the size of Los Angeles’ Black community at one stroke—who accepted twenty-two and a half cents an hour to work for the Pacific Electric Railway. They were joined in strikebreaking by a smaller number of unemployed Japanese workers, and even a few Mexicans who ignored community pressures and crossed the picket lines.

The wives and girlfriends of the strikers didn’t give up. On one occasion a few dozen of them confronted the scabs, going so far as to attempt to wrestle their tools away. They were chased off by police.

Despite the solidarity of the local labor movement and militant actions such as the women’s, the strike could not be sustained. Unlike the situation Wheeler found in Oxnard, Biddle could build on no ongoing relationship between the groups of workers. The Mexican track laborers replicated the results of the Anglo streetcar drivers and conductors, who had attempted union campaigns for the previous three years running, but failed to crack Huntington’s open shop citadel. The Carmen were at a disadvantage; Huntington had persuaded the obedient city government to place policemen in every streetcar, and infiltrated the union with hired detectives.

At this time such defeats were predictable and occurred far more often than worker victories. But the first few years of the twentieth century offered more of an opening, thanks to an economy that needed workers, and experienced militant workers willing to risk their jobs—and sometimes more—to organize a union.

Successful organizing

As a result, a startling number of successful organizing drives occurred around the city. Waiters and waitresses, building tradesmen, garment workers, candy makers, teamsters and laundry workers found their way to collective action and unions. In all, more than 122 new locals were chartered between 1900 and 1904. The city’s union membership jumped from just over two thousand to nearly ten thousand.

This was small potatoes compared to San Francisco, the heart of the closed shop in California, and one of the strongest union towns in America. But soon after the 1906 earthquake, San Francisco labor was forced to face a problem created by its own successes. Union leaders were warned by powerful businessmen that the competition from open shop Los Angeles would eventually either drive San Francisco owners into bankruptcy, or force them to reduce wages in the northern city. These representatives of business issued a challenge to San Francisco labor: organize Los Angeles and level the California labor market playing field, or be prepared for the consequences.

Building Trades Council leader and San Francisco mayor P. H. McCarthy and other northern labor leaders took the warning seriously. They raised money and dispatched organizers to southern California, sparking a resurgence of organizing at the end of the decade. These activities brought Los Angeles labor to a new peak of membership and militancy. By 1910, the growing Los Angeles labor movement boasted 12,000 members. Several large strikes were in progress by mid-year. Hundreds of angry union activists were willing to test the new anti-picketing ordinance, filling the county jails. A full collision loomed between workers intent on expanding their share of the pie and Otis’s open shop forces.

Fred Glass is the author of From Mission to Microchip: A History of the California Labor Movement (UC Press, 2016) and a former member of the State Committee of California DSA

Stay tuned for next week’s installment…