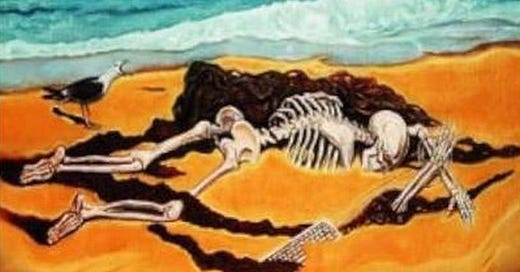

Image credit: Perry Vasquez

Welcome, dear readers.

As the mission statement for this virtual soapbox notes, the Jumping-Off Place takes its name from a 1931 Edmund Wilson piece where he observes what melancholic reading the coroner records are with their tales of the suicides of those who came to the utopia of the West to escape poverty and health woes only “to see the end of their resources in the empty California sun.” Wilson’s ruminations should be mandatory reading for anyone who wants to delve into the secret history of our tourist mecca where only “happy happens” according to the official record.

As opposed to the boosters’ rose-colored view of the city, Wilson saw a place where:

Brokers and bankers, architects and citrus ranchers, farmers, housewives, building contractors, salesmen of groceries and real estate, proprietors of poolrooms, music stores and hotels, marines and supply-corps lieutenants, molders, machinists, oil-well drillers, auto mechanics, carpenters, tailors, soft-drink merchants, cooks and barbers, teamsters, stage drivers, longshoremen, laborers—mostly Anglo-Saxon whites, though with a certain number of Danes, Swedes and Germans and a sprinkling of Chinese, Japanese, Mexicans, Negroes, Indians and Filipinos—ill, retired or down on their luck—

they stuff up the cracks of their doors in the little boarding-houses that take in invalids, and turn on the gas; they go into their back sheds or back kitchens and swallow Lysol or eat ant-paste; they drive their cars into dark alleys and shoot themselves in the back seat; they hang themselves in hotel bedrooms, take overdoses of sulphonal or barbital, stab themselves with carving-knives on the municipal golf- course; or they throw themselves into the placid blue bay, where the gray battleships and cruisers of the government guard the limits of their enormous nation—already reaching out in the eighties for the sugar plantations of Honolulu.

Perhaps no other characterization of San Diego was less welcome in the polite circles of our local boosters until the public art project that greeted Super Bowl week visitors to our fair city in 1988 with an infamous piece of agit prop art by Elizabeth Sisco, Louis Hock, and David Avalos that rechristened our hometown, “America’s Finest Tourist Plantation.” As Artforum noted at the time:

[T]his was the slogan that taunted the citizens of San Diego from the rear advertising panel of nearly one-half of the city’s buses during the month of January. It was art with a message inextricably tied to a specific place and time . . . San Diego is a city with a boosterish attitude, based mostly on the climate and waterfront; it loves to call itself “America’s Finest City.” It is also a city that reportedly relies heavily on illegal immigrants for its support workers, including many in the tourist trade. January 1988 was Super Bowl month, a first for San Diego, and a much touted event for a tourist-hungry urban area.

The message implies that San Diego’s comfort is dependent on a hidden slave population. The photographs make the same point with a cropped image of a handcuffed man and a lawman (focusing on the manacled wrists and holstered gun), flanked by similarly cropped images of a man scraping food from a plate, on the left, and a chambermaid bringing fresh towels to a hotel room, on the right . . . The artists turned it into a major media event, getting the press (including myself as a local journalist/art critic) to provide amplification of the work as it hit the streets. The execution of the event was as much a part of the art as the work itself

The artists set out to publicize the plight of undocumented migrant workers, and they used the theater of the real world very effectively to achieve that goal. They decided that Super Bowl month in the National Football League’s host city would be a vulnerable time to bring out the dark secrets of the tourist industry there, and it was; city leaders reacted with horror.

Cultural/political moments such as this one have occasionally served as lightning flashes that have illuminated San Diego’s darker corners but the theme of innocent fun in the sun devoid of any social, political, or economic complications continues to be a dominant current in our fair metropolis.

Thirty years later, 15 years after the publication of the radical history, Under the Perfect Sun: The San Diego Tourists Never See, that I co-wrote with Kelly Mayhew and Mike Davis, I published a San Diego Free Press column with a title that gave a tip of the hat to that seminal piece of 1980s agit prop art that observed that:

It should come as no surprise to anyone who ventures outside San Diego’s hermetically sealed and relentlessly marketed image of itself as a carefree paradise by the sea that the reality of our city is quite different than the happy fantasy. A recent study by the Public Religion Research Institute (PRRI) confirmed this recently when it released a report that noted of America’s Finest City, “45% of San Diegans fall into an auspicious category: people who work full time and still struggle with poverty.”

The local news coverage of this report understandably focused on the poverty numbers and how here and elsewhere in California, people are losing faith in the American Dream. Digging deeper into the report, we also learn that working Californians suffer great housing insecurity, feel disposable as employees, have negative workplace experiences, and aren’t sure they’ll ever be able to retire. While these are all noteworthy and grim details, several other things, buried toward the end of the study, give some signs of hope but also present a central challenge.

More specifically, worker organizing has huge support in California. As the PRRI report states, “support for organizing among workers is robust across different racial and ethnic groups, but there are varying degrees of intensity. More than eight in ten (85%) Hispanic Californians, more than seven in ten black (77%), and API (71%) Californians, and more than six in ten (64%) white Californians to say that worker organizing is important.” And looking to the future, younger Californians are even more likely to support worker organizing than their older neighbors.

When it comes to economics, it appears that there is a fair amount of class consciousness in the Golden State. In fact, the residents of the land of endless summers aren’t in a mellow mood when it comes to income inequality and its effects on political power.

Today, even as San Diego has shed its Anglo-Saxonist, ultra-conservative Republican, anti-union skin and experienced a seismic political shift with Democrats now occupying the mayor’s office, controlling the entire City Council, and enjoying a majority on the County Board of Supervisors, we are still haunted by the ghosts of San Diego’s past. Many San Diegans still suffer from poverty, inequality, a lack of affordable housing, homelessness and a host of other social and economic ills that don’t neatly fit our postcard image of ourselves.

As the recent flooding illustrates, the costs of economic inequality and climate change in San Diego are disproportionately felt by communities of color, and the urge to cosmetically “solve” intractable issues like homelessness by simply sweeping folks up off the streets and moving them out of the view of tourists and more affluent residents is a temptation that some Democratic politicians simply can’t resist. Of course, their critics to the right are advocating more draconian measures, such as setting up camps like Sunbreak Ranch, to permanently protect the comfortable from the afflicted.

Thus, while some things are clearly better in San Diego, there is still far more work to be done by those who want to organize the unorganized, comfort the afflicted, and fight for social justice across the board. The Jumping-Off Place is dedicated to those ongoing struggles and to giving a space for other kinds of cultural criticism, writing, poetry, and art as more and more sites dedicated to creative voices vanish from our landscape. We may even cover some sports with a critical lens.

Enjoy, fellow workers and friends!