By Peter Zschiesche

San Diego shipyards and our unions there are very different today than they were 50 years ago.

They were shaped by their own unique history of organizing and the changing nature of the shipbuilding and ship repair industry that grew so much due to the US Navy’s expansion during and after World War II. Back then work was especially hard, dangerous, and underpaid.

The workforce was diverse and multinational. Shipyard workers from Scotland, Ireland, Portugal, and Greece found work as recent European immigrants. Filipinos often came to the shipyards after exiting the Navy. Vietnamese came in as refugees of the Vietnam War. Mexicans and local Chicanos had a large presence. Most trades had Navy veterans that brought shipyard skills from their time in the service. Women, African Americans, and white veterans often entered NASSCO that way.

As a former shipyard worker at NASSCO and Southwest Marine I offer this short, limited accounting of local shipyards and how shipyard unions were organized over the last 50 years. There are others who are still around and who were active shipyard workers back then, and they may have a different story. I chose this story for the union lessons I believe in.

I worked as an Outside and Inside Machinist at NASSCO before being elected twice as its Union Business Representative. The six other union leaders there selected me to serve as Chair of the Seven Union Coordinated Bargaining Committee from 1986-1994. It was a worthy, wild ride full of lessons for union organizing, hard bargaining, and creative struggle built through rank-and-file activism. Our joint union work made us stronger in the fight for all union workers there.

1970s: The peak of union power on the waterfront.

The 1970s were a decade of union dominance in the shipyards and among many of the smaller shops near the waterfront that serviced those yards with specialized work. There was traditional bargaining between each individual union and the shipyard companies. Union negotiations for better wages and benefits were hard fought but shipyard wages and benefits were lower than in other local industrial union contracts. There was no coordinated bargaining like in the Pacific Coast Metal Trades Councils at some other west coast shipyards. Despite union dominance on the waterfront there were no big union organizing drives. For local union leaders, getting workers’ fair share seemed hard enough.

Safety and health were major issues at all the shipyards. The work was very physical and wore down the bodies of those who made their careers in the yards. According to pension records of the 1980s NASSCO workers who reached retirement age lived an average of 3 years after retirement. There was no OSHA law to help protect workers until 1978. And for those lucky enough to live longer, the pensions were shamefully low.

During the early 1970s the attitudes of shipyard workers were influenced by the many protest movements all around them and among some shipyard workers themselves. Newer workers entered the yards as veterans of the Vietnam war, young black and brown community activists, and women seeking non-traditional work in the trades. They all enjoyed the power and protection of union shop contracts that were never questioned by waterfront employers at the time. They did not hesitate to strike in order to get the best from collective bargaining.

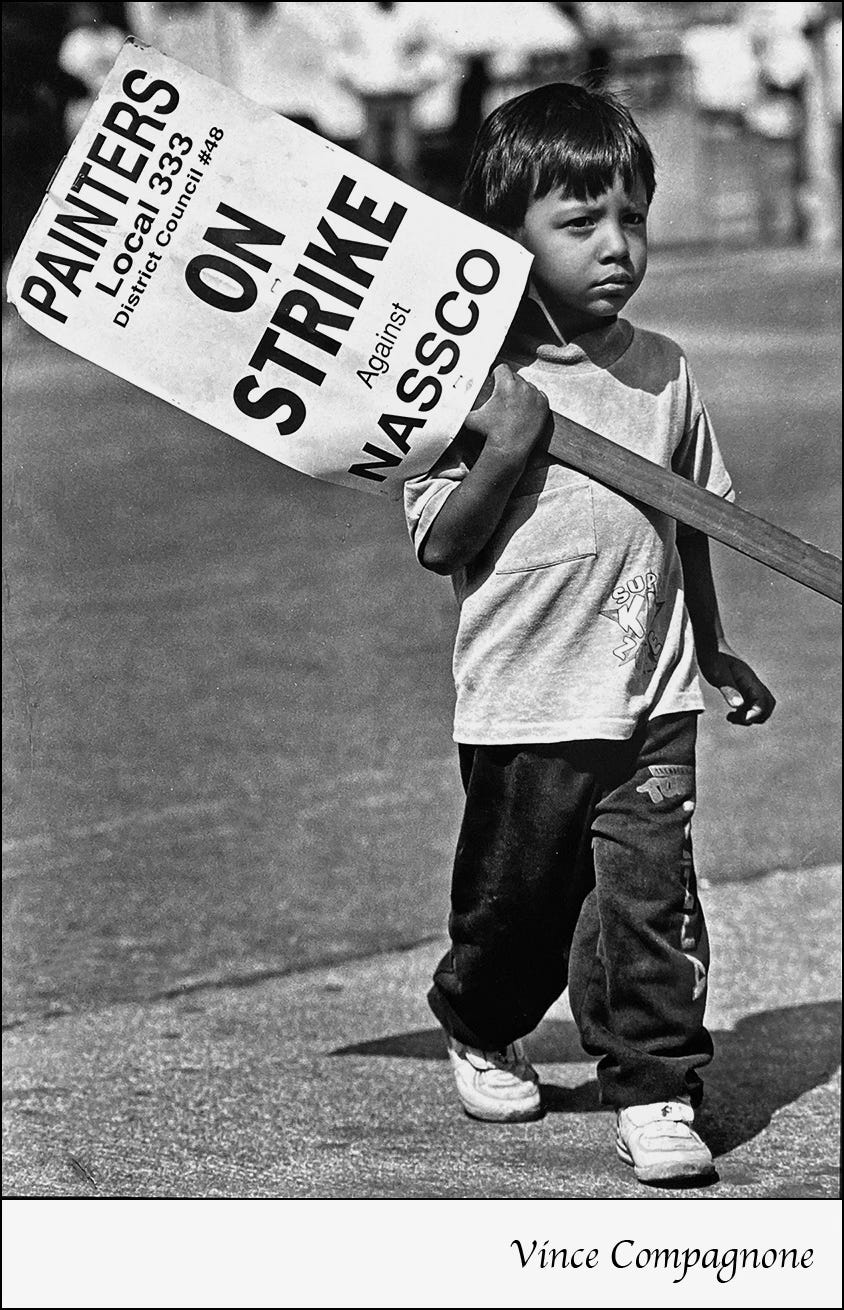

NASSCO was by far the largest shipyard on San Diego’s waterfront with many thousands of workers (up to 7,000) when new construction was booming. Shipyard workers were represented by one of 7 unions in the AFL-CIO: Ironworkers in Local 627, Machinists in Local 389, Electricians in IBEW Local 569, Carpenters in Local 1300, Painters in Local 333, Teamsters in Local 36, and Operating Engineers in Local 501. The Ironworkers and Machinists unions represented the various metal trades, and the Carpenters union represented not only carpenters but also the large group of “ways men” (like laborers). Operating Engineers ran the big cranes. NASSCO was building large tankers and Navy ships and repairing Navy vessels.

The two smaller shipyards on San Diego’s waterfront, San Diego Marine and Campbell Shipyard each had many hundreds of workers depending on the amount of smaller ship and boat building and repair they had going on. Several unions represented the trades there: Machinists Local 389, Carpenters Local 1300, Electricians Local 569, & Painters Local 333.

There were smaller union shops off the waterfront that serviced the shipyards, including:

Triple A (Boilermakers Union); Fraser Boiler (Machinists Union); Pacific Marine Propeller (Machinists Union); Pac Ord then/L3 now (Machinists & Electricians); Western Pump (Machinists Union); M. Slayen (Machinists Union), Hopeman Brothers (Carpenters), and many others.

Some of the shipyard unions were shop locals of international unions in the Building Trades – the Ironworkers, Carpenters, Boilermakers, and Operating Engineers. Some of them were building trades local themselves – the Electricians in Local 569, Teamsters in Local 36 and Painters in Local 333.

Machinists Local 389 was in large and small yards and shops that were not part of the over 20,000 aerospace and manufacturing workers in the large industrial plants of General Dynamics, Rohr, and Solar Turbines. These workers had their own Machinists Union locals.

NASSCO unions struck in 1975 and 1978. The unions at Campbell Shipyard also struck in 1975. Few workers crossed the unions’ aggressive picket lines. Negotiations were tough and contract gains were modest, but there were no attacks on the unions themselves. Meanwhile business was slowing and by the end of the decade the two smaller shipyards, San Diego Marine and Campbell Industries, were losing business and up for sale.

.

1980s: NASSCO as the center of union activism

The 1980s were years of transition in local shipyards and saw the rise of non-union shipyards on the waterfront. Triple A and San Diego Marine went out of business early on. The owners of Triple A created Southwest Marine which took over the space of San Diego Marine at the foot of Sampson Street. It became the largest non-union shipyard on our waterfront without any struggle from shipyard unions at the time. In 1986-87 NASSCO union locals got active members out on leave to organize at Southwest Marine but there was no support from their international unions. This was a serious oversight for all the 7 unions at NASSCO.

Later on, Southwest Marine was bought by a large conglomerate, BAE Systems. Campbell Industries went out of business and eventually Continental Maritime took over space nearby at the foot of Cesar Chavez Parkway. Like Southwest Marine it was never organized by our unions. These are repair yards that do not compete for NASSCO’s new construction but they do compete for Navy repair work and are the base of nonunion shipyard workers in the area.

The smaller off-waterfront union shops also went out of business or became non-union shops (ex. – North Star Propeller in Barrio Logan). One exception is Pac Ord – now L3, which remains union. While the seven unions remained strong at NASSCO and represented the majority of local shipyard workers, the shipyard unions as a whole lost a lot of their power to create better wages and benefits for all shipyard workers in San Diego. Non-union subcontractors from San Diego and around the country, especially from yards in the south, replaced those smaller shops that had serviced local shipyards. Subcontracting to non-union outfits became the norm instead of the exception and was another blow to union power on our waterfront.

These changes left the NASSCO unions at the center of union activity on the waterfront. In September, 1980 two machinists died on the job, which elevated union activism around terrible health and safety conditions in the shipyard. Radical activists disrupted a Navy ceremony inside the yard and a bunch of union workers were fired. One year later, the 1981 union negotiations and a strike created a new approach to health and safety – a joint union-management health and safety committee that used concepts from the new 1978 Occupational Safety and Health Act. OSHA became an important tool for unions to improve and enforce shipyard safety.

The contract language created a joint union-management safety committee where the seven unions could “officially” work together. The unions met to select three (3) full-time union safety representatives – one from each of three unions - to help educate and enforce good safety practices in the yard. Their powers included the right to shut down work that was unsafe. The seven unions selected their reps and urged them to be aggressive with large rolls of orange tape that they could use to identify immediate dangers/safety violations and get production suspended until the conditions were corrected. This was new union power that the union safety representatives used to build and demonstrate that power on the job.

Each union selected its own delegates to the joint safety committee that met monthly during work hours to create better safety conditions, including regular communications with shipyard workers through bi-lingual leaflets and lunch-time meetings in the yard. Union activists from the seven different unions built unity and trust through working together on health and safety issues and developed ties with organizations outside the yard on these issues, including the UCSD School of Medicine and the new Environmental Health Coalition – both focused on worker and community health.

The seven unions’ leaders did not build on this joint work to create coordinated bargaining during the 1984 negotiations but there were raised expectations from rank-and-file activists for them to communicate and cooperate more at that time. The unions struck again in 1984 as they had every three years since 1975. They negotiated another set of 3-year contracts which would be the last 3-year union shop contracts they negotiated for the next 40 years.

In 1985 NASSCO management met with union representatives of the seven unions and described the loss of future contracts and the need for wage cuts in the next contract if the company expected to survive. Throughout this period NASSCO was owned by Morrison-Knudsen, a world-wide construction company. Wage cuts had never been on the table.

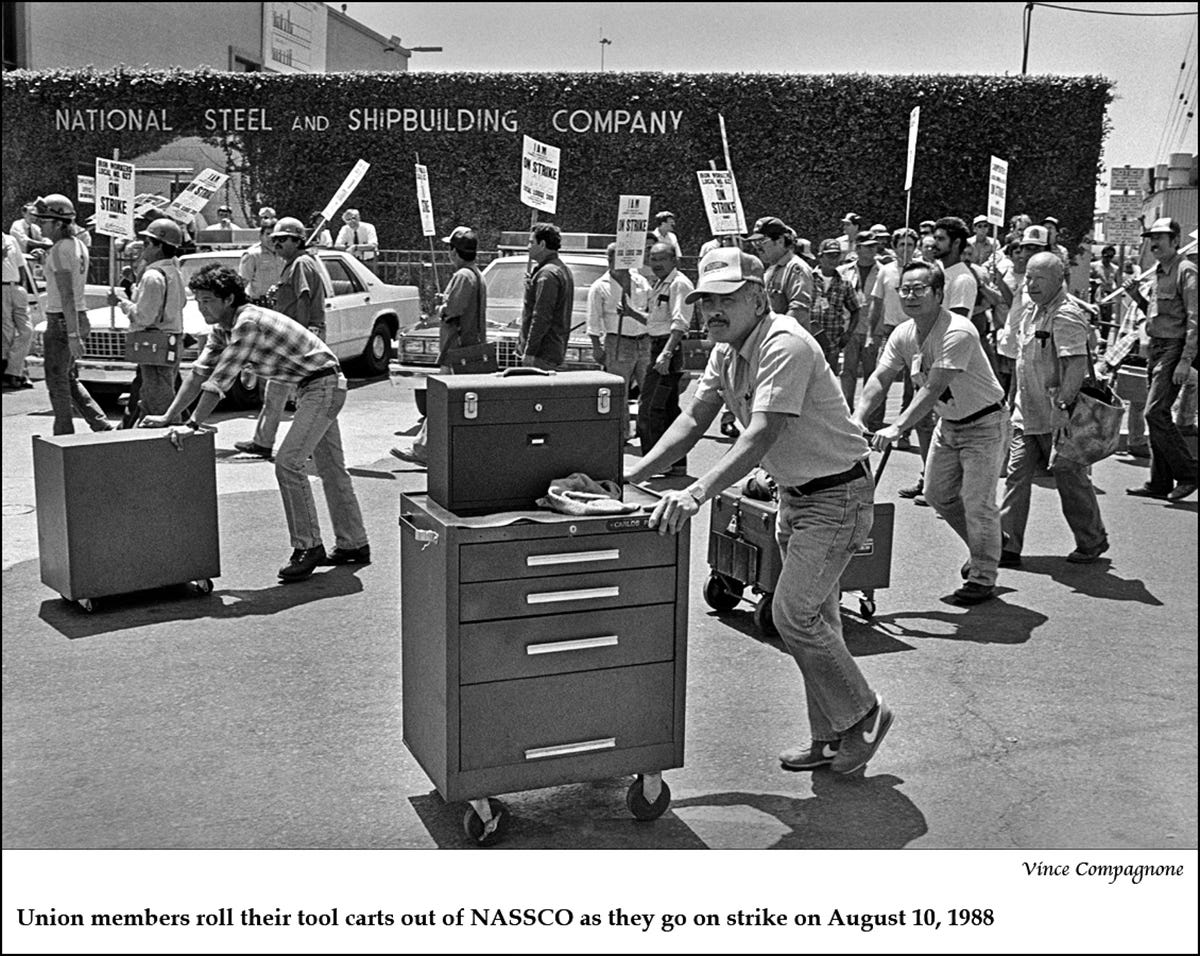

Then In 1986, union representatives, some of which were newly elected, met to discuss how to respond to management’s early threats of wage cuts during the 1987 negotiations. They created the Seven Union Coordinated BargainingCommittee and chose a chair of that new committee. They began meeting to discuss their common issues long before the 1987 negotiations began. This process developed trust among the unions and made each other familiar with the issues of each union. This was the first time that the seven unions built union power through organized solidarity in contract negotiations. They needed it badly.

NASSCO, July 11, 1987. “Six civilian shipyard workers were killed and six others injured, one of them critically, when a crane-operated steel basket carrying the men plunged nearly 30 feet onto the deck of a U.S. Navy ship early Friday morning. NASSCO, which builds and repairs commercial and military ships, employs about 2,300 workers at the shipyard, located just south of downtown San Diego. The accident is the latest in a series of mishaps at the shipyard that, before Friday, had resulted in five deaths in the last seven years, according to company officials.” (Los Angeles Times)

The 1987 negotiations were tough and wage decreases remained in the company’s final offer with the biggest wage cuts (almost 50%) coming in the non-journeyperson trades. Local unemployment was 9% and the danger of replacement workers was real. Under President Reagan the permanent replacement of strikers with strike breakers had become law. Locally, in the summer of 1987 Solar Turbines retained its strike breakers as permanent employees when it settled its strike by the Machinists Union. These contract negotiations were a tough test for a new way of bargaining – coordinated with all seven unions in the room but with no rules to govern their work. Decisions were made by consensus among all the unions, big and small.

At the end of September, in a tremendous break with its waterfront tradition, the seven unions refused the company’s final offer but decided not to strike right away. Instead, they worked without a contract for the next eleven months and activists in the different unions spearheaded workers’ opposition to the company’s demands from inside the yard. They borrowed the “Inside Game” from shipyard workers at Dillingham Shipyard in Oregon and encouraged workers to “work to rule” and resist cooperative work patterns while the unions continued to bargain for a better contract. This prolonged struggle by all the unions built much unity among union leaders and shipyard workers themselves. It also caught the company by surprise and without tools to cope. The many decentralized work processes in the shipyard were vulnerable to workers’ resistance. Workers found new ways to struggle and still, at the end, waged a short strike to push back. The seven unions would not find this level of union and worker solidarity again.

The 1988-1992 contract did not avoid wage cuts but did introduce a profit-sharing plan under which shipyard workers would recover some of those cuts in future years, which they did. It also created new efforts by NASSCO management to work with the unions on certain issues. The unions helped NASSCO bring the Exxon Valdez tanker, which was leaking oil into the sea just outside San Diego’s harbor, into its shipyard for major repairs by bringing environmental allies into negotiations of that process. Union leaders lobbied Congress for more federal funds and new double-hull requirements for tankers that would reduce oil tanker spills like those from the Exxon Valdez. In 1989 NASSCO’s 4 top management bought out Morrison Knudsen and with the seven unions’ approval created an ESOP for all employees which created future payouts of over $50,000 for those workers with seniority.

The 1990s: The end of the union shop at NASSCO

This was the decade that the seven unions at NASSCO and their coordinated struggles fell apart. The unions prepared for coordinated bargaining again in 1992. But they faced a new kind of management - one that locally owned the company through the top-heavy ESOP and had never shouldered the full weight of multi-union negotiations. They were on their own and hired the big Littler-Mendelson anti-union management consultant firm to guide their negotiations. It was going to be a dog fight!

NASSCO’s 1992 proposals to the seven unions were like nothing ever seen on our waterfront before. Their “final offer” prior to the end of the existing union contract was full of extreme takeaways, including seniority rights – the bedrock of job security – and health plan benefits. All during contract negotiations management did not budge – these takeaways were not “bargaining chips” to counter the unions’ demands. They became NASSCO’s bottom line.

Unlike in 1987, the unions decided to strike and stayed out for three weeks until the company agreed to return to the bargaining table. By now union workers knew how to “work to rule” to exert power in the negotiations, but the struggle became another long one. The company soon stopped dues check-off and union membership fell dramatically. It was a year later in 1993 before negotiations moved to resolve the many issues, and that momentum carried early into 1994. Then coordinate bargaining began faltering and tactical errors were made. Some union leaders and their members were getting anxious and tired of the prolonged negotiations.

At the same time Ironworkers Local 627 and its International had issues and Ironworker International representatives began meeting with management separately from the other six unions and without coordinating or informing them. Then in spring of 1994, management announced that it would no longer accept a union shop security clause. That was the heaviest blow. From this point forward NASSCO was an open shop with no signed contract in sight.

During 1994 the seven international unions took over coordinated bargaining with no new results. There was at least one strike during that time, but several unions withdrew from any activity at the yards or in union efforts at negotiations. In the late 1990s union activists from Ironworkers Local 627 organized a decertification of their union and won. They formed the Shipyard Workers Union independent of the AFL-CIO. They followed that victory with successful union decertification drives among several other of the seven unions using an anti-AFL-CIO message. Given the fact that these unions had abandoned any efforts to help their members at the shipyard, this was an easy message to hear. The Shipyard Workers Union then won representation elections for the bargaining units of Carpenters, Painters, and Teamsters. Later, IBEW 569 agreed to let their Electricians join the Machinists Union at the yard.

The 2000s

In 2000 the Machinists Union restarted collective bargaining with NASSCO and signed a 7-year contract that included an open shop (union membership optional). The larger Shipyard Workers Union soon followed and did the same. However, coordinated bargaining was a thing of the past. These two unions have negotiated their contracts separately ever since that time. The big change was that the Shipyard Workers Union affiliated with the International Boilermakers Union and rejoined the AFL-CIO and our San Diego-Imperial Counties Labor Council. These two unions hold the future of our remaining organized shipyard workers in their hands. Our local Labor movement is more active than ever now, and I am sure both the San Diego-Imperial Counties Labor Council and the San Diego County Building & Construction Trades Council stand ready to bring local AFL-CIO Labor Solidarity to help when asked.

In the 2020s General Dynamics (GD) NASSCO won large new construction contracts with the US Navy and just recently announced new long-term contract for even more Navy construction of new ships. They have no economic reason to keep insisting on the “open shop” provisions of the two union contracts. They inherited the NASSCO contract when they bought the shipyard from the four local owners in 1998.

General Dynamics is a corporate giant that has union shop contracts at other US shipyards. But on our waterfront, they want greater power over our local workers who make them profitable and earn them more contracts. And there are still deaths and dangerous working conditions. We should remember that in August this year, J C Adame, a pipefitter for almost 39 years of production at NASSCO, died when a heavy metal structure fell on him where he was working.

GD NASSCO management purposely denies its production workers the right to full union representation through the union shop, where everyone pays dues and has a voice at the bargaining table. In an open shop, all workers in a “bargaining unit” are represented by a union even if they are not dues-paying union members. But in the open shop only union members get to negotiate and vote on their contract with the company. The most fundamental and democratic right of union workers – to negotiate and vote on their pay, benefits and working conditions - is denied to the union bargaining units at GD NASSCO.

If GD NASSCO considers itself a good corporate citizen of our democracy, then why not let its workforce decide whether or not they want full union representation? Let all represented workers at NASSCO get the chance to choose their power—depend on GD or be union!

Peter Zschiesche is a retired Machinist Union member, who served as President and Business Manager in IAM Local 389. He is also the founder of the Employee Rights Center and was elected to the San Diego Community College District Board of Trustees, where he served for 16 years. Currently, he is on the Board of the United Taxi Workers of San Diego.