I got a text from my son that the ex-President was grazed by a bullet during a rally in rural Pennsylvania while I was in my room at the Mirage in Las Vegas. A rally-goer was dead, and another was gravely wounded.

We turned on the TV and watched the footage play over and over in a closed feedback loop. The instant analysis shaped and edited the narrative in real time as we looked and listened. It was bewildering, as usual, but we sat and gave the newscasters our rapt attention. We were part of something larger than ourselves, a national, global community of passive spectators. Cynical and innocent at the same time—hijacked by the instantly packaged spectacle of the event that had taken over our lives.

There was the mandatory piety of the intrusive reporters and news anchors. We switched around, but they were all the same channel. The crucial moment, the bloody ear, the clenched fist, the unhinged guy in the crowd flipping-off the camera, played again and again and again.

The news immediately filled me with a sense of dread and menace. Nothing good would come from it.

It was 118 degrees outside, and you could see the Trump Hotel and Casino looming just down the Strip. Earlier that day, I’d read that climate change was altering time. As the news told me: “They found the impact of climate change on day length has increased significantly . . . We have to consider that we are now influencing Earth’s orientation in space so much that we are dominating effects that have been in action for billions of years.”

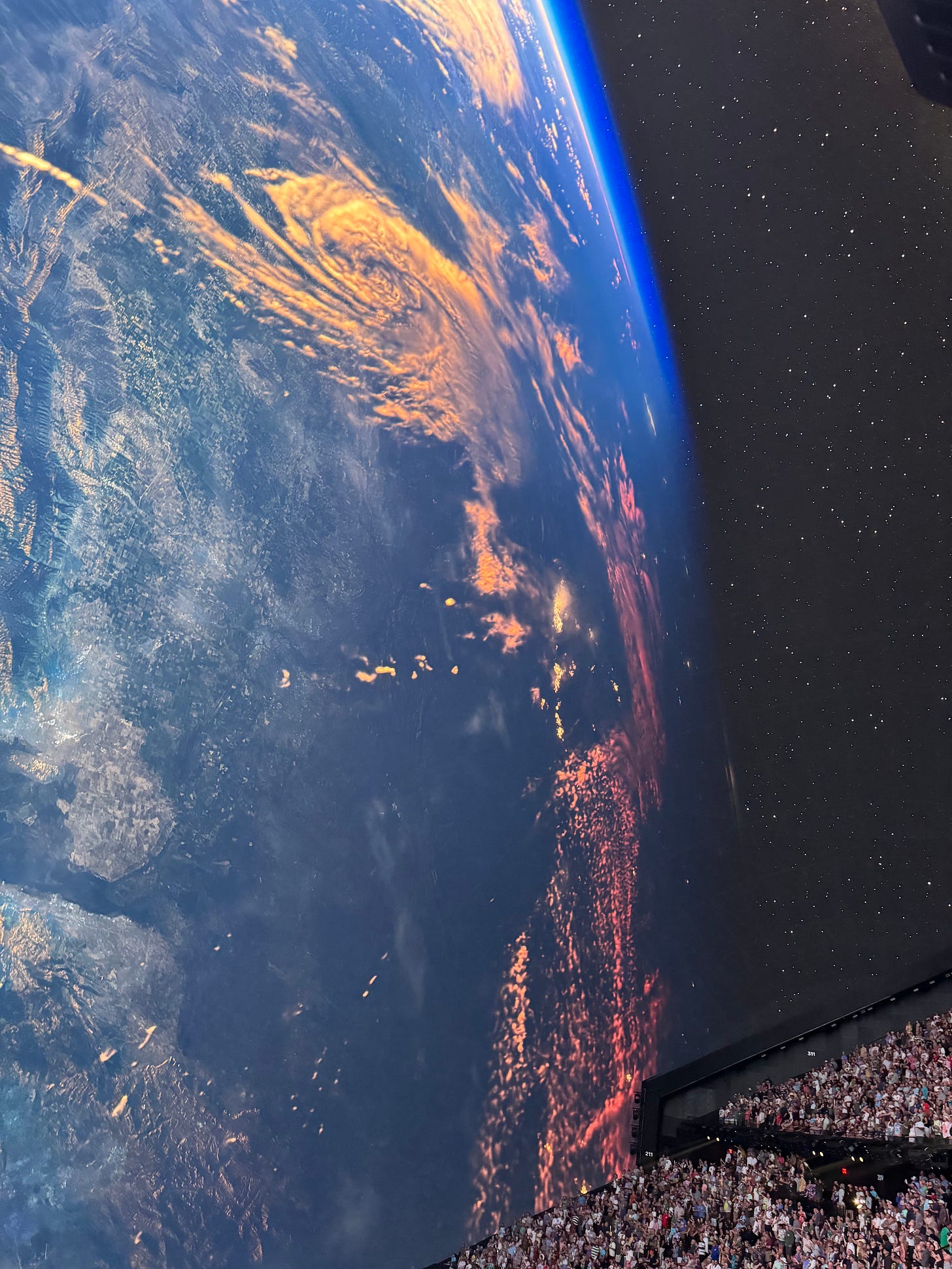

The night before, we’d seen Dead and Company at the Sphere where the visual effects are so powerful they can make you feel like you are flying, even if you are sober as a judge. That evening the most striking song was Bob Weir doing a retooled version of “A Hard Rain’s Gonna Fall” by Bob Dylan. It was a half-step slower than the original and delivered in a sage-like fashion:

Oh, what did you see, my blue-eyed son?

Oh, what did you see, my darling young one?

I saw a newborn baby with wild wolves all around it

I saw a highway of diamonds with nobody on it

I saw a black branch with blood that kept drippin’

I saw a room full of men with their hammers a-bleedin’

I saw a white ladder all covered with water

I saw ten thousand talkers whose tongues were all broken

I saw guns and sharp swords in the hands of young children

And it’s a hard, and it’s a hard, it’s a hard, it’s a hard

And it’s a hard rain’s a-gonna fall

Back at the Mirage, the hotel was honoring its final weekend before being demolished by dispensing over a million dollars on loaded slot machines for those fortunate enough to hit the button at the right moment. The frenzy this evoked in the crowded casino was palpable as people jockeyed for seats, pushed one another, and got into fistfights. We saw several people being escorted out by hordes of security guards and police. One couple got into a heated argument, cursing each other as they were publicly humiliated and dumped on the scorching sidewalk outside.

It was so hot in Las Vegas that drunk tourists and homeless people had been hospitalized with third-degree burns after too much contact with the sidewalk. As extreme heat continues to break records, the homeless regularly die from it and the situation is getting worse with every passing year.

Each day we were there, a different worker at the Mirage told me yet another tale of madness, depravity, and violence. It was a total shitshow. It was, as Hunter S. Thompson put it, “a savage journey into the heart of the American dream.” People were ready to kill each other over their last little dollar.

The furies, it seems, have been released. It was hard not to see it as an omen of things to come.

I was down with Covid back in San Diego in the weeks before the trip to Las Vegas, which we took to celebrate my one-year survival after almost dying of autoimmune liver failure. They gave me antiviral infusions at the hospital for a few days, and I cleared the virus in a couple weeks without any complications, despite my weakened immune system from my medications.

Not everyone is so lucky.

Being immunocompromised as I am after my transplant surgery makes being in a crowd anywhere, particularly in Vegas, risky, so I mask up there and elsewhere when appropriate. Even with rising case numbers, almost nobody else does, anywhere. So, I stand out. After one of the Vegas Dead shows we saw, a woman in a tie-dye t-shirt chased me down across the casino floor, cursed me, and yelled, “Take off your fucking mask! Covid is over!”

Sunshine daydream.

A few weeks earlier, a fat middle-aged guy did the same thing at a Padres game. In the current context, the mask seems to be a target for folks who’ve been told they should assail people like me. I’ve noticed that I get the side-eye more frequently in public. Sometimes people mutter insults under their breath as they pass me by.

Lots of small things are different. There has not been much comity out there for a good while now, but, from my peculiar new vantage point, we may be getting even closer to the point where all is permitted if the target of your animus is assumed to be an enemy of real Americans. My insignificant corner of the universe is not unique; it’s just a spot where, if I look carefully, I can see the tip of the cultural iceberg.

On the night after Trump was shot, we walked through the crowds in the casino, and no one acted as if something historic had just happened. Rabid gamblers kept jostling for seats at slot machines, pounding cocktails, and making losing bets on baseball. Outside on the way to our final show at the Sphere, my son said that, except for the concerts, what small sociological interest he had had in Vegas had disappeared. Underneath the flashing lights, he noted, “it’s just a bunch of well-dressed people walking by a bunch of desperate people on the street like they don’t even exist. It’s the ugliest side of America—the epitome of late-stage capitalism.”

So much for our holiday amidst other people’s misery.

My kid was right—we were there in the middle of it all, consuming commodified, recycled counterculture, buying t-shirts, trying to enjoy the ride for at least one evening as the country went to hell in a bucket. Was there still something about music and collective joy that redeemed the experience in any way? I liked to think so as I walked down the long corridor towards the gilded pleasure dome, but I didn’t really know.

Nothing, it seemed, could escape being swallowed up by the market as even the “fuck you” refusal of punk rock had made its way to Vegas with aging punkers floating in the luxurious pool at the Golden Nugget after their nostalgia fest the last time we were in town. At the time, I was amused by the easy co-optation of an angry subculture, how seamlessly it was gulped into the belly of the Las Vegas beast. Of course, that was just “entertainment” dressed up as resistance rather than “real” rebellion, right? I’d be back to teaching and doing union and activist work soon enough but was that enough to redeem the moment? Despite my desire to think so, I didn’t know about that either.

As I walked on, I was reminded of old graduate school arguments about hegemony and resistance and whether there is an “outside” of our seemingly all-encompassing systems of power. Our dissent is commodified and sold back to us in every way imaginable. And yet we persist.

During one of the Dead shows as the spectacle of a mountain vista unfolded for the audience in the comfortably air-conditioned theatre, I thought that perhaps I was sitting in the future where, as the world warmed to unsustainable levels, those of us with resources would continue to live and over-consume as always in completely artificial environments, blocking out the death of nature as we experienced a reproduced version of it while downing the beverage of our choice or enjoying a perfectly curated high in seats that vibrated to the music.

Outside, others would suffer and die without even a social media meme to commemorate their existence.

***

The revolution on the right was televised.

It was one part Fascist spectacle, one part Vegas lounge act. There were professional wrestlers, washed up rock stars, golf pros, and a host of other cheap stage props. Trump kissed the helmet of the firefighter who died at his rally, wore a bandage on his ear, inspiring his devoted throng to also do so in solidarity. He read a few nice things off the teleprompter, evoked the divine, anointed himself savior, and went on an incoherent dictator-style address that proved to be the longest ever convention nomination acceptance speech.

Newsflash: we should hate immigrants. We should hate Democrats. We should hate student protests. We should hate all the stuff he hates.

Yawn.

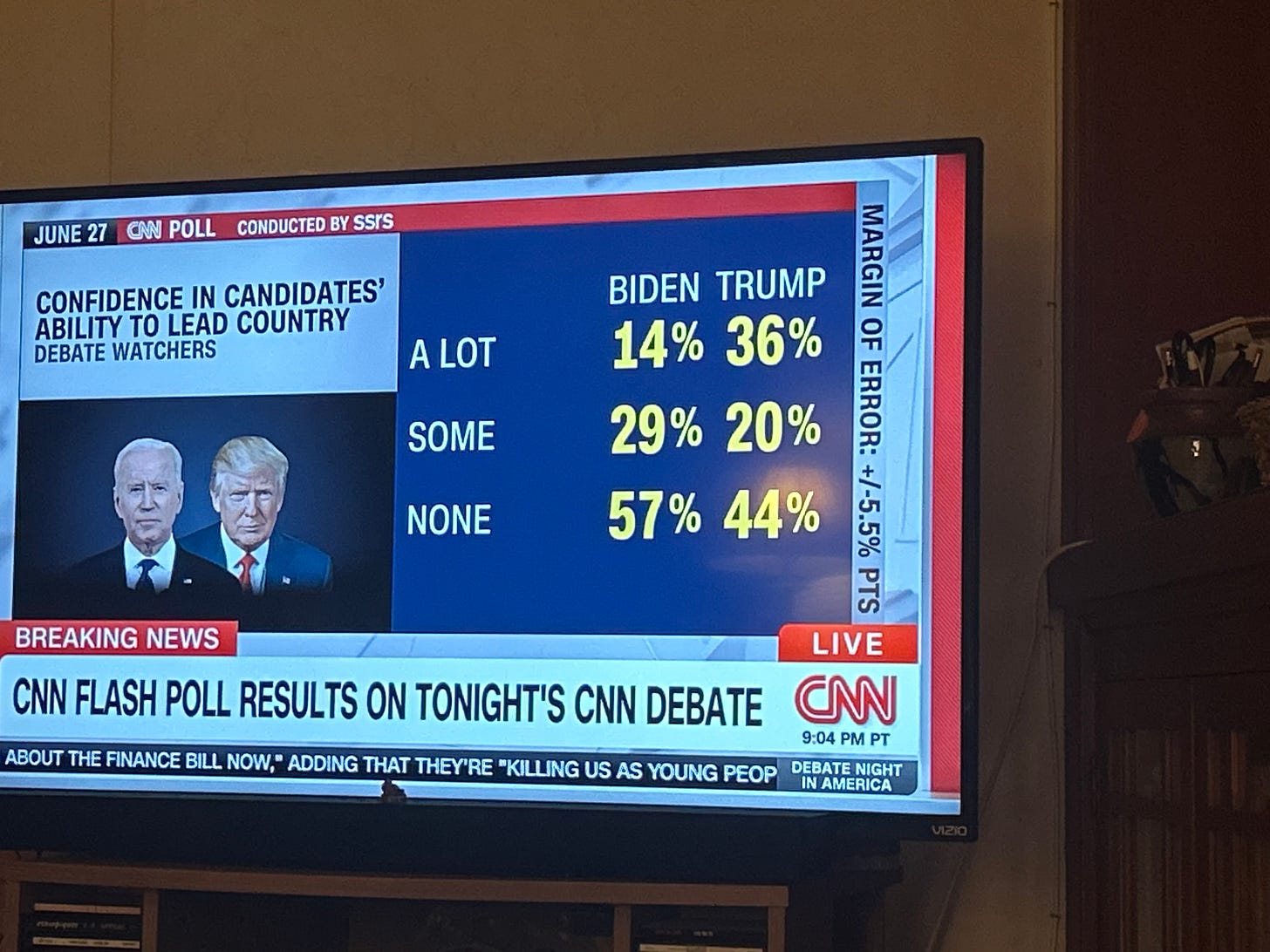

People were leaving the arena before he finished. It was a train wreck of epic proportions. But the polls still showed him winning, and it seemed that nothing would move the needle away from creeping dystopia.

In the days that followed, the Republican National Convention evoked a nearly universal wave of fear, loathing, depression, bickering, despair, and other unpleasant emotions amongst my circle of friends, family, colleagues, and fellow activists. There were social media posts, texts, calls, and face-to-face conversations about how to fight back, switch candidates, and/or flee the country. Folks made bad jokes, shared Onion articles, hatched conspiracy theories, angrily backed the sitting President, grieved the death of any sense of normalcy, gave very serious analysis while urging very serious action, and more.

And outside those circles, summer rolled on. People went to baseball games, hit the beach, packed the bars in the Gaslamp, comingled with tourists, and largely ignored or were simply totally unaware of the high stakes of the current crisis.

The weather in town was perfect, our beloved cat suddenly became gravely ill, camps of homeless neighbors came and went across the street from the house we rent, and we tried to do what we could to hold onto the things and people we love even as the outside world and the winds of history seemed to turn against us.

At the last show we saw in Las Vegas, Bob Weir performed yet another classic, stark, existentialist Dylan song. In his slow, wavering, aged voice he sang, “Forget the dead you’ve left, they will not follow you/The Vagabond who’s rapping at your door/Is standing in the clothes that you once wore/Strike another match, go start anew/And it’s all over now, baby blue.”

That was the feeling we had for a few days in the middle of July 2024.

***

I was watching the Padres game against the Guardians when I checked the New York Times on my phone during a commercial, three minutes after Biden dropped out of the race. First, I texted my wife at the vet. “Wow,” she replied. After that my son walked in the front door, and I told him, “Biden’s out.”

The Padres scored two runs in the top of the second. Most of the time, the team that scores first in baseball wins, but not always.

We switched between cable news and the ballgame as history happened yet again, only a little more than a week after the shooting and days after the GOP Convention. My phone blew up as it had in Las Vegas. It was full of shock, glee, sorrow, relief, speculation, disbelief, and more. The talking heads on TV wrote and rewrote the narrative as events unfolded.

People endorsed Kamala Harris in lockstep, called for an open convention, reported record fundraising for the presumed Democratic candidate. One could almost feel the collective spirit of half the country rising as each hour passed. The Republicans were unhappy and searching for a way to shape the conversation in their favor again. It was like the player representing the winning run for team GOP had been called out after video review.

Three outs now. New ballgame.

Michael King was mowing down the Cleveland batters as the Padres held onto their slim lead; highlights from the Cardinals game showed players mimicking Trump’s post-shooting fist pump after getting big hits.

You just can’t make this shit up.

The next day, in her first speech after Biden stepped down, Harris addressed a room of campaign supporters, spoke with love, joy, and ferocity as she thanked Biden, attacked Trump, and evoked a dream of a more just and inclusive America. She was sharp as a razor. Whatever, policy differences one may have had with her in the past, it was inarguable that this was a seminal moment in American history.

Maybe team dystopia was not going to win after all. It was far too early to tell, but history was sprinting forward again and suddenly, anything seemed possible at any moment.

***

Last Wednesday, Israeli Prime Minister Netanyahu gave a speech to Congress attacking American protestors of the war in Gaza as pro-Hamas Iranian proxies who were nothing more than useful idiots. Representative Rashida Tlaib of Michigan sat quietly and held up a sign that said “Guilty of Genocide” on one side and “War Criminal” on the other.

Some Democrats cheered, others sat without clapping, about half refused to come at all. Outside, protests raged on the streets, and the talking heads on TV debated which way the youth vote would swing. Pro-Harris or stay home?

Most of the discerning, politically active young people I talk to resent being forced into a corner where they either must support what they see as horrible policy or be labeled antisemitic. There is no room for nuance. That political cul-de-sac is a dangerous place for a split Democratic party and the future of democracy in the United States.

As the week moved on, Harris issued a statement condemning the protesters, another expressing sympathy for the human suffering in Gaza. Republicans called her a DEI candidate. Would she pick a centrist white man in a swing state for VP? Netanyahu went to visit Trump at Mar-a-Lago. Polls showed Harris narrowing Trump’s lead or even pulling ahead. The talking heads on MSNBC were giddy. What clever meme will the kids come up with next? Snoop Dogg helped deliver the Olympic torch in Paris.

Our cat died on the foot of the bed in our guest room, and we cried.

Dylan Cease threw the second no-hitter ever for the Padres. History kept whizzing ahead at a ferocious pace. In another week, I’ll be back in the fray, preparing to teach classes on U.S. labor history and early American literature and doing political work for my union, the American Federation of Teachers, one of the first national unions to endorse Harris. My labor siblings and I will be running campaigns for local school board races and doing what little we can to positively influence the national contest that will determine so much about our futures, particularly for folks younger than me.

What kind of “we” will we become? That question weighs heavily upon me. I’ll do what I can, however modest, and hope.

Nobody knows what will happen.

Note on the Summer Chronicles:

A decade ago, during my time writing for the OB Rag and SD Free Press, I penned a series of pieces over the summer that moved beyond the blog/column form to something a little looser and more open to improvisation and the poetic turn. Last summer, a health crisis intervened, but I made it through to the other side of that and here I am again, writing, word by word, breath by breath.

Below is the original preface for the first series of chronicles:

In the summer of 1967, the great Brazilian writer, Clarice Lispector, began a seven year stint as a writer for Jornal de Brasil [The Brazilian News ] not as a reporter but as a writer of "chronicles," a genre peculiar to Brazil. As Giovanni Pontiero puts it in the preface to Selected Chrônicas, a chronicle, "allows poets and writers to address a wider readership on a vast range of topics and themes. The general tone is one of greater freedom and intimacy than one finds in comparable articles or columns in the European or U.S. Press."

What Lispector left us with is an eccentric collection of "aphorisms, diary entries, reminiscences, travel notes, interviews, serialized stories, essays, loosely defined as chronicles." As a novelist, Pontiero tells us, Lispector was anxious about her relationship with the genre, apprehensive of writing too much and too often, of, as she put it, "contaminating the word." It was a genre alien to her introspective nature and one that challenged her to adapt.

More than forty years later, in Southern California—in San Diego no less—I look to Lispector with sufficient humility and irony from my place on the far margins of literary history with three novels and a few other books largely set in our minor league corner of the universe. Along with this weekly column, it's not much compared to the gravitas of someone like Lispector. So, as Allen Ginsberg once said of Whitman, "I touch your book and feel absurd."

Nonetheless the urge to narrate persists. Along with Lispector, I am cursed with it—for better or worse. So for a few lazy weeks of summer, I will try my hand at the form.