Struggle for the 8-Hour Day

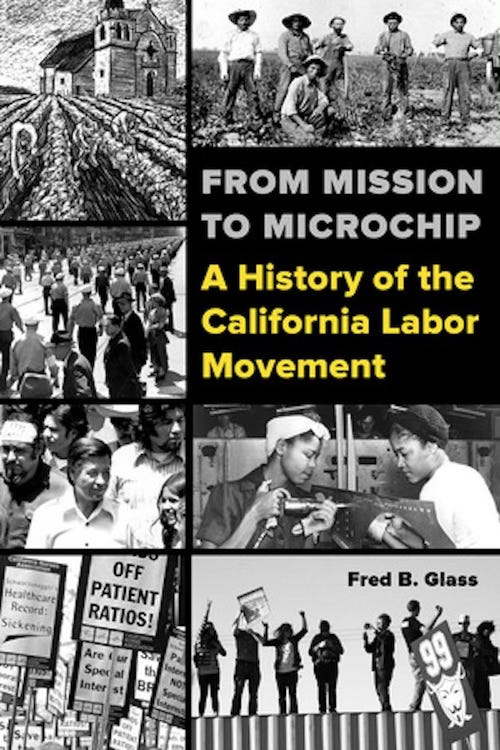

The Labor History Corner--an excerpt from From Mission to Microchip: A History of the California Labor Movement By Fred Glass

A version of this article appeared on the California Labor Federation California Labor History website. You can buy From Mission to Microchip: A History of the California Labor Movement from the University of California Press.

Struggle for the 8-Hour Day

In 1863 a prolonged strike of tailors for higher pay led to the formation of the first central labor body in the state, the San Francisco Trades’ Union. Fifteen unions from diverse trades joined to coordinate activities of common interest to their members. The outstanding leader of the San Francisco Trades’ Union was Alexander Kenaday.

The son of Irish immigrants, Kenaday was born in Virginia in 1824. His parents moved to Saint Louis, where Kenaday learned the printing trade. Like Mark Twain, he worked on a Mississippi River steamboat for a time. He joined the U.S. Army during the Mexican War, earning sergeant’s stripes. He had returned East at the end of the war when news reached him of the discovery of gold. Retracing his steps to California, he prospected without success until he decided a printer in San Francisco might make a better living than a miner. Working for various newspapers, he helped to organize the Typographical Society, and later served as its president.

Under the leadership of Kenaday, the Trades’ Union facilitated “the giving of moral and material aid in times of distress” to its unions, generating support for workers during strikes.

The organization was also central to building a movement, beginning in 1865, for an eight hour day law for all California workers. A state ten hour law had passed in 1853, but was only loosely enforced. Most trades with active unions had achieved a ten-hour day by the mid-1860s, but within a six day work week. In dry goods stores (which sold non-perishable products), salespeople formed a Clerks’ Association. It successfully waged a struggle for “early closing”—which at that time meant 8 p.m. In 1863 bakers struck successfully for a twelve hour, six day week. This may not sound like much of a victory—until we learn that previous to the strike they worked fourteen hours, seven days a week!

Thus, when Kenaday, through the Trades’ Union, issued a call for “…the passage of a law constituting eight hours a legal day’s work…”, his words resonated. After a series of meetings in December 1865, Kenaday was armed with a resolution and instructions to convince San Francisco’s delegation to the state legislature to pass such a measure. At his own expense, he spent the next few months lobbying and organizing.

Many impatient workers didn’t wait for a law. In December, the union of ship caulkers (workers who sealed ships water-tight) struck and became the first granted the new hours. Other maritime unions quickly achieved the same goal in the early part of 1866, some by walking off the job, others through simpler negotiations with their employers.

In February, the state assembly passed a version of the eight hour bill and sent it to the state senate. Kenaday presented a 22-foot long petition with 11,000 signatures supporting the eight hour day to the senate. But after vocal opposition from the iron trades employers association, the bill was narrowly defeated.

The San Francisco Trades’ Union lasted only a few years—it was dead by mid-1866—but the interest in coordinated action continued. In 1866 and 1867, union by union, and sometimes in groups, activists created “eight hour leagues” and presented employers with demands for eight hour days, and with a date by which the employer had to comply. By June of 1867, the Morning Call newspaper acknowledged that “despite the existence of Eight-Hour Laws in other communities, the fact exists that the eight-hour system is more in vogue in this city than in any other part of the world, although there are no laws to enforce it.”

A mass parade and demonstration in San Francisco bolstered the movement that same month. The marching order of the unions was determined by who had achieved their eight hour day first. Reflecting the strength of the most well organized workers, the procession was dominated by skilled tradesmen from the construction, ship-building, and metal industries. One newspaper observed that

There was nothing incendiary in the nature of their speeches; no threats were indulged in, nor any efforts made to intimidate those who disagreed with them, but they evidenced a determination to achieve success by proper and legitimate means.

Despite the show of strength, only a few thousand workers were employed under eight hour contracts, out of 60,000 in the city. Employers formed a ‘ten hour league society’ in response to the workers’ movement. Ship employers, starting with the Pacific Mail Steamship Company, fired employees who had been working eight hours, and advertised back east for replacement workers. A compromise was reached when the fired workers were allowed to return at eight hours per day, but with a slight cut in pay.

At the end of the year unions created the Mechanics State Council. (The term “mechanic” referred to skilled craft workers in any trade—not, as we mostly use it today, to mean someone who works on engines.) It was formed to promote the eight-hour movement throughout California. Within months General A. M. Winn, a retired carpenter and state militia officer, helped the State Council to enroll 23 unions, with a membership of eleven thousand workers. Fifty leagues affiliated with the Council, including activists in Sacramento, Oakland, Vallejo, San Jose and Los Angeles.

Momentum grew until the San Francisco Board of Supervisors passed a law establishing the eight-hour day in all city and county employment. Finally in February 1868 an eight-hour day law for all California workers was passed by the state assembly and state senate, and signed by the governor. A huge torchlight procession in San Francisco celebrated passage of the law, the second statewide eight-hour law in the country (after Illinois the previous year). Far from perfect—the law lacked effective enforcement mechanisms—it nonetheless marked a high-water point for the struggle for a shorter workday.

It meant that perhaps a few hours, wrested from the long work week, might allow “the mechanic and citizen to pass his leisure under the control of mechanics.”

Fred Glass is the author of From Mission to Microchip: A History of the California Labor Movement (UC Press, 2016) and a former member of the State Committee of California DSA

Stay tuned for next week’s installment…

Fred Glass is the author of From Mission to Microchip: A History of the California Labor Movement (UC Press, 2016) and a former member of the State Committee of California DSA

Stay tuned for next week’s installment…