SWIMMING WITH THE SHARKS: Or, Crime Does Pay (Big) in New York’s Gilded Age

Book Report: Americana

By Mel Freilicher

Queen of Thieves: The True Story of “Marm” Mandelbaum and Her Gangs of New York by J. North Conway on Skyhorse Books, 2014

As the city’s premier fence, Fredericka “Marm” Mandelbaum, a German-Jewish immigrant, accumulated more money and power than any woman in the Gilded Age, inconceivable for a woman engaged in legitimate business. A July 1884 New York Times article called her “the nucleus and center of the whole organization of crime in New York City.”

J. North Conway documents her quite infamous career: particularly illuminating are the many passages from contemporaneous periodicals. Marm began as purveyor of stolen wares to dry goods merchants, legitimate commercial establishments, and numerous individuals, some in the underworld: first as a pushcart peddler, then out of a storefront on the lower east side, connected to a warehouse chock full of purloined merchandise of all kinds. It’s believed she herself never stole anything but worked strictly as a fence.

Marm was intimately connected to Tammany Hall, the Democratic Party’s utterly corrupt political machine. Later in her career, she financed some of the “most daring and successful bank robberies ever perpetrated,” stated the Times. Marm also ran a school for crime for 6 years, where young boys and girls were taught by professionals to be pickpockets, and sneak thieves, with advanced classes in safecracking and burglary.

She herself mentored major female crime figures who became high class thieves and ran confidence schemes. Quoted as saying she wanted to help any women who “are not wasting life being a housekeeper,” some contemporary feminist historians view Mandelbaum as a Gilded Age heroine.

And she got away with it all! It’s estimated Marm handled between 1 and 5 million dollars’ worth of stolen goods until she fled the country in 1884, while out on bail, with an estimated fortune of one million dollars. (Canada had no real extradition treaty with the U.S. until the 1970s.) Upon leaving, she even managed to transfer various real estate holdings into her daughters’ names—tenements and warehouses in New Jersey and Brooklyn, mostly used to store stolen merchandise—so the law couldn’t touch them.

The obstacles Fredericka Mandelbaum faced were truly staggering. She and her husband, Wolf, emigrated from Germany due to the failed 1848 revolution, and the potato blight coming on top of almost insurmountable anti-Semitism. Wolf was a peddler: his choice of occupations severely limited by anti-Semitic laws, including disproportionate taxes on Jews, even prohibitions on marrying. A Jewish man who wanted to marry had to purchase an expensive certificate, known as a matrikel, proving he was working in a respectable job.

Marm voyaged to America in steerage class with their one-year old daughter, Bessie. Being confined below deck to a passageway that was seven feet long, two feet wide with a ceiling of six feet was particularly difficult since Fredericka herself was nearly six feet tall and weighed over 250 pounds. The press was often vicious about her massive girth.

A January 1884 New York Times article described, “a gross woman, a German Jewess, with heavy, almost masculine features, restless black eyes, and a dark, unhealthy looking complexion. Her stout figure was incased in a rich sealskin cloak…On her big hand were brown kid gloves…On her head rested a black bonnet with beads and bright colored feathers.”

Arriving safely in New York despite epidemics of cholera and dysentery endemic to steerage class, they were reunited with Wolf. But the infant Bessie died a few years later in the Kleindeutschland (Little Germany) slum where the Mandelbaums lived in one room, in a tenement with no indoor plumbing, heating or sewage disposal.

Health Department records from the period indicated nearly 75% of children under the age of 2 died each year from rampant strains of tuberculosis, typhus, cholera, chicken pox, poor nutrition and sanitation. Sixty-five immigrant children died to every 8 non-immigrant children. The highly industrialized 6-block area of their neighborhood was home to more than 3,600 people as well as iron foundries, brick and sewing machine factories, and coal, lumber, lime and stone yards.

Husband and wife both became successful street peddlers. Continually expanding her contacts, it was said Fredericka never bought any stolen goods unless she already had a buyer in mind. By 1865, the Mandelbaums were able to move to a nearby clapboard house with an attached store and basement for storage.

From all accounts, Fredericka was a devoted mother to her 4 children. When Wolf became seriously ill with tuberculosis in 1870, she dutifully cared for him for 5 years until his death. Seemingly, he had no part in the evolution of her criminal enterprise which dramatically accelerated after his death.

In her residence, just one block from a police station, Marm built an elaborate hiding apparatus within the store: behind a chimney with a fake back was a dumbwaiter operated by a secret lever. Dealing in just about everything that came her way—not just silk, lace, diamonds, gold and silver, but also horses and carriages—for a sizable profit, she ended up selling a large portion of the property looted during the Chicago fire of 1871.

Steadily building her clientele while being schooled by some of the city’s top criminals, Marm’s efforts were greatly facilitated by the reign of William Marcy Tweed, ultra-corrupt leader of Tammany Hall, the Democratic Party political machine: controlling the treasury, judiciary, all city contracts, and money-making operations, including gambling dens, and houses of prostitution.

Within 3 miles of City Hall were more than 4000 prostitutes (opium addiction being a chief occupational hazard), inhabiting approximately 400 brothels, some of which established telegraphic communication with the police department to be warned of any impending raids, and to summon help.

Between 1865 and 1871, Tweed and his gang stole anywhere from $30 million to $200 million from the city, with the Criminal Courts building project at the heart of their empire. Begun in 1861 with a projected cost of $350,000, by 1869, nearly $11 million had been spent.

In his Low Life: Lures and Snares of Old New York, Luc Santé (now Lucy) notes Boss Tweed’s great influence over newspapers as well: the World was his organ in the days before Joseph Pulitzer bought the paper from Jay Gould (who originally purchased it to use as leverage to buy Western Union); one of the three directors of the Times was Tweed’s business partner; at one point, he was paying the Post $50,000 a month.

The Tweed Ring garnered huge profits from the development of the upper east side, especially Yorkville and Harlem, at the cost of tripling the city’s bond debt to nearly $90 million. Buying up undeveloped property, they’d use their resources to improve the value of the land—such as installing pipes to bring water from the Croton Aqueduct—before selling it. Santé also points out Tweed’s generous side. He created a public works project, built and supported a variety of hospitals, orphanages, schools, churches and old soldiers’ homes.

By 1870, Boss Tweed’s worth was estimated at $12 million. Third richest landowner in the City, proprietor of the Metropolitan Hotel, and the New York Printing Company, he was also President of the Guardian Savings Bank, on the board of directors of the Brooklyn Bridge Company, and thanks to Jay Gould, a director of both the Tenth National Bank and the Erie Railroad. Gould had wrested controlling interest of the railroad from Cornelius Vanderbilt due to a $1 million bribe to the New York State legislature to legalize the issuing of $8 million in “watered stock” (stock not representing real value).

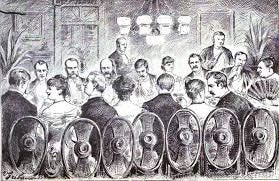

Marm loved to throw lavish dinner parties á la Mrs. Astor where the criminal fraternity mingled with the social elite—judges, lawyers, politicians. Clearly, whether such lines had ever been more than theoretical, they were utterly obliterated by the rapaciousness of the robber barons and their political functionaries. In fact, Boss Tweed, who she’d been paying off for years, was Marm’s frequent dinner guest.

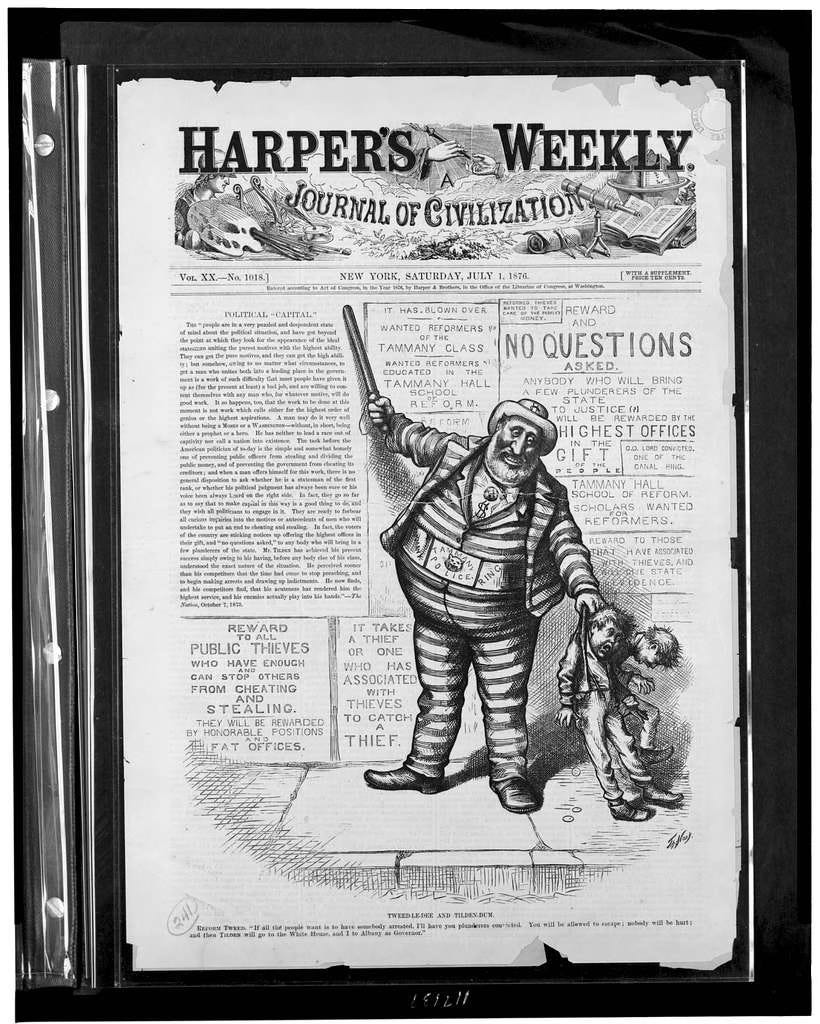

By 1871, the Times and Harper’s were publishing damning evidence, supplied by a disgruntled insider, of the Tweed Ring’s corruption, especially regarding kickbacks to contractors. For example, the city spent $10,000 on $75 worth of pencils, $171,000 for $4,000 worth of tables and chairs, and $23,000 for 36 awnings. Boss Tweed was convicted on 90 of 120 counts for stealing, as estimated by an aldermen’s committee, between $25 and $45 million from the city.

Finally given a 12-year prison sentence, it was rumored Marm financed Tweed’s escape, while under guard, first to Cuba then to Spain. But the U.S. government arranged for his arrest at the Spanish border where he was recognized from Thomas Nast’s political cartoons in Harper’s Weekly (always featuring his prominent diamond stickpin). Held till a Navy cruiser arrived to bring him back to the states, Boss Tweed died in a New York jail.

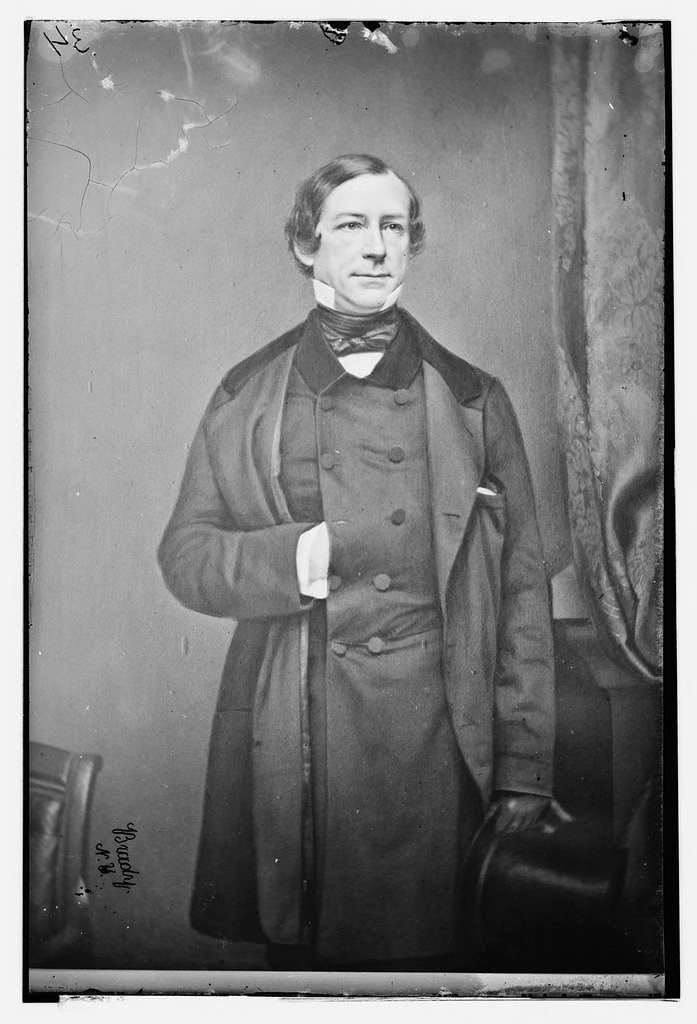

Tweed’s infamy was almost matched by that of Fernando Wood, who began as a reformist, viewed as Tweed’s nemesis, and became, arguably, the most corrupt mayor in New York City history. In 1857, the New York State legislature passed laws to replace the Municipal Police, a kind of private militia controlled by Mayor Wood’s office, with a state-run force. Wood refused to disband his militia which surrounded City Hall to protect him; a riot broke out between the competing squadrons. Wood was arrested but never tried.

The following fall, the Court of Appeals affirmed the decision to disband the Municipal Police. Meanwhile, that summer, “the city was in a state of chaos,” Santé points out. Whenever a cop from one force made an arrest, someone from the other squadron would set the prisoner free. Additionally, “the competing forces continually raided each other’s station houses and freed en masse the prisoners.” As Herbert Asbury relates in his 1927 study, The Gangs of New York, “gangsters and other criminals ran wild…reveling in an orgy of loot, murder, and disorder.”

Asbury revels in examples: the Five Point Gang broke into the Green Dragon, a Bowery Boys hangout, and “after wrecking the bar-room and ripping up the floor of the dance hall, proceeded to drink all of the liquor in the place.” In another incident, beleaguered police managed to clear the streets of a mob, forcing scores of Dead Rabbits and Bowery Boys into adjacent houses, and up the stairs to the roofs. ”One desperate gangster” was knocked off a roof; “his skull was fractured when he hit the sidewalk. His enemies promptly stomped him to death.”

In 1856, Abijah Ingraham created a kind of white paper, addressed to leading New York businessmen, documenting “the model mayor’s” plunder since 1850, when he swindled his friend Edward E. Marvine by overinflating costs for Wood’s own get-rich-quick scheme involving California’s gold rush. Reprinted in the Cornell University Library Digital Collections, “A History of the Private, Political, and Official Villanies of Fernando Wood” is full of facts, figures, and court documents regarding multiple fraudulent accounts of purchases in food, liquor, tobacco, household and office staples, as well as Wood’s “false, forged and simulated bills” to many legal firms and merchants.

Technical and well documented, “A History…” also reveals the author’s personal revulsion: claiming to have affidavits from individuals who were told a story by Wood, “entirely too disgusting for publication…invented, no doubt…to show his utter contempt for the Irish, and more especially Catholic priesthood.”

In his travels, Wood related, he was forced to spend a night sharing an attic bed with a Catholic priest, who instead of climbing down a ladder, “quietly relieved himself” in his under garment. “In the morning he says he complained bitterly to the priest of the disagreeable condition of the bed.”

Despite being driven from office, Fernando Wood was reelected as a Democrat in 1860, opposing the coming Civil War. Before the presidential election, Wood’s brother, Benjamin, editor of the New York Daily News, warned readers: If Republicans win, “we shall find negroes among us thicker than blackberries swarming everywhere.” Other editors predicted, “You will have to compete with the labor of four million emancipated negroes.”

Openly siding with the Confederacy, Wood suggested if the Union dissolved, New York should declare it was “a free city of itself.” (Afterwards, he spent 14 years in the House of Representatives, vigorously opposing the 13th Amendment to the Constitution, abolishing slavery). “With our aggrieved brethren of the slave states, we have friendly relations and a common sympathy,” he told the press.

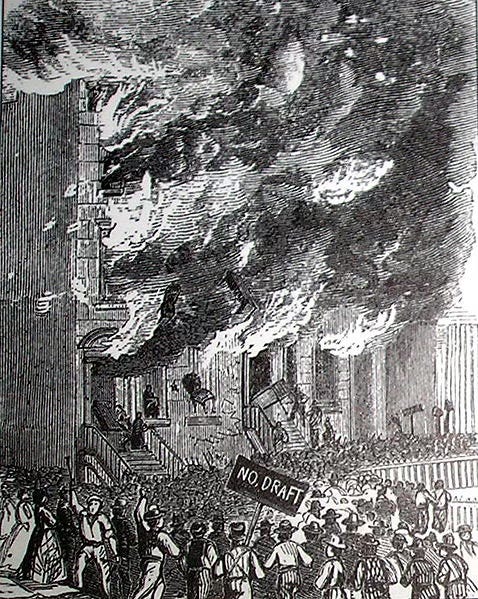

A sentiment evidently popular with much of the electorate. An estimated 50 to 70 thousand people participated in the Anti-Conscription riots of 1863, a week-long orgy of destruction; some individual mobs swarming through the streets “contained as many as l0,000 frenzied men and women,” Asbury notes. Smaller mobs roamed around Manhattan Island from the Hudson to the East Rivers, “looting, burning, and beating every Negro who dared show himself.”

Asbury’s blow-by-blow descriptions of the devastation are vivid, to say the least. On the first day of the rioting, three black men were hanged; afterwards, an average of three a day “were found by police hanging to trees and lampposts, their bodies slashed by knives or beaten almost to a pulp. Some were little more than charred skeletons, for the women who followed in the wake of the rioters and on occasion took part in the fierce fighting, poured oil into the knife cuts and set fire to it and then danced beneath the blazing human torch with obscene songs and imprecations.”

While the Second Avenue Armory was being sacked, detachments of police arrived, clubbing down rioters rushing from the building, some of whom set it on fire. By the time the barred door was ripped open from its hinges, “the whole building below the third floor was a roaring torch…and frenzied rioters began leaping from the windows.”

When the floor of the drill room collapsed, “the screaming men were hurled into the flames.” Afterwards, workmen carted away more than fifty baskets and barrels of human bones from the ruins and buried them in Potter’s Field.

Wealthy looking individuals, and enterprises were set upon to shouts of “There goes a $300 man!” The Enlistment Act of 1863 mandated a draftee could pay $300 for a “substitute” to take his place--about $5000 in today’s money. All the robber barons took advantage of this option, of course. Many started building their fortunes by selling shoddy or obsolete materials to both sides.

Horace Greeley’s liberal Tribune office was broken into, and set on fire, but the crowd was driven off by police brought in from quieter Brooklyn. Not surprisingly, Wall Street was the best-defended area in the entire city: from the rooftop, employees of the Bank Note Company readied tanks of sulfuric acid to spill on any attackers.

Brooks Brothers was particularly hated: in 1861, they’d been awarded a shady government contract for 12,000 Union uniforms, many of which were ill-fitting, poorly sewn, lacking buttons and even buttonholes. It was later discovered the uniforms had been made of old, shredded decaying rags, glued together into what vaguely resembled cloth. Harper’s Weekly and the New York Herald made much of the $45,000 the New York State legislature (nearly $11 million in today’s economy) had to pay for replacements.

Edwin G. Burrows’ and Mike Wallace’s compelling, meticulously researched, 1365-page, 1999 Pulitzer Prize winning Gotham: A History of New York City to 1898 describes more Draft Riot mayhem. Homes of wealthy Republicans were trashed, commuter trains stoned, a group of Irishwomen crowbarred up the tracks of one of the lines, neighborhoods were barricaded. “As small isolated detachments of police reserves were sent into the area they were routed and stomped their bodies stripped, their faces smashed.”

“Bands of Irish longshoremen, with quarrymen, street pavers, teamsters and cartmen began chasing blacks, screaming ‘Kill all niggers!’” Blacks were dragged off streetcars and stages around City Hall. Racially mixed couples were especially targeted. Waterfront tenements, dance halls, brothels, bars and boarding houses which catered to black workingmen were attacked. Black neighborhoods in lower New York were set upon; bands of boys would mark houses by stoning windows, then return with older men to finish the job.

The 237 children (mostly under twelve- years-old) housed in the Colored Orphan Asylum were heroically rescued by a young Patrick McCafferty who shepherded them to the 20th Precinct building while the crowd screamed “burn the niggers’ nest,” and “smashed pianos, carried off carpets and iron bedsteads, uprooted the trees, shrubs, and fences, then set the building ablaze.”

Asbury notes one Negro girl didn’t get away; found hiding under a bed, she was mercilessly slaughtered. Crowds attacked other moral reform projects, even those not associated with blacks, like the Magdalene Asylum and the Five Points Mission.

The riots finally ended when Secretary of War Stanton sent in federal troop--which would have been dangerous even a day earlier. After Gettysburg, Lee’s army, wounded and enraged, had remained in the area, and Union forces had been tied down in blocking a possible move northward. Lee escaped south across the Potomac the night before the Mayor’s request for troops came through.

After the Civil War, Marm, who never took a public position on slavery, revved up her operations considerably: quite successfully planning and financing major crimes, especially bank robberies. Investing about $2500 to purchase the most modern tools to carry out the 1878 Manhattan Savings Institution heist which netted nearly $3 million in cash and securities. Some of the burglars were caught, but detectives could never link Marm to the robbery.

Some of her “little chicks,” as Marm called the pack of master criminals she cultivated, were declassé bluebloods, like Charlie Bullard: boarding school educated and classically trained, with ancestors reaching back to the Mayflower. With long, nimble fingers, ”Piano Charlie” played the instrument like a professional, was an expert safecracker, and one of the city’s most skilled and daring burglars.

The invaluable Bullard entertained her dinner guests, playing anything from Beethoven’s “Sonata in C sharp minor” to the popular “Little Brown Jug” on the white baby grand that adorned Marm’s extravagant dining room. His skills as a butcher also provided the finest cuts of meat for her dinner parties.

Arrested during a train robbery, Marm wasn’t about to let Bullard languish in jail. When William Howe and Abraham Hummel, the city’s premier criminal defense lawyers who Marm kept on a $5000 a year retainer, failed to get “Piano Charlie” released, she assembled a team of several protégés. They successfully broke him out of the White Plains, New York jail, led by another key player: calling himself “the Baron,” Max Shinburn `wore expensive clothes, sometimes donning a full-length ermine cape.

Shinburn eventually sailed to Europe where by judicious expenditures he actually bought the title of Baron Shindel of Monaco. But he was sent to prison in Belgium in 1883, then again in upstate New York. Finally released in 1908, Shinburn wrote a history of safecracking, with the presumably unintentionally ironic title, Safe Burglary: Its Beginnings and Progress: deemed so instructive for novices it was never published, and remains to this day in the Pinkerton Detective Agency archives.

In their forty-odd year tenure, Howe and Hummel represented more than 1000 defendants in murder and manslaughter cases alone, with Howe as the main litigator: “a corpulent, flashily dressed practitioner noted for his overwhelmingly theatrical manner, much given to weeping in the courtroom,” according to Luc Sante. The mainstay of their practice was breach-of-promise blackmail suits, representing showgirls who’d been dropped by society figures, many of whom kept the firm on retainer as protection against further suits.

Low Life lists some of their more colorful clients, including entire gangs such as the Sheeny Mob, and “the foremost downtown gang of their day, the Whyos,” counterfeiters, bookmakers, the procuress Hattie Adams and the French Madame, the abortionist Madame Restell, Tammany bosses, bunco artists, dive owners, and “such once famous murderers as Dr. Jakob Rosenzweig (the Hackensack Mad Monster), and Anne Walden, the Man-Killing Race-Track Girl.”

Clients in civil cases included exotic dancer Little Egypt, the publisher of Police Gazette, the anarchist Johann Most, “bohemian feminists” Victoria Woodhull and Tennessee Clafflin, and a slew of theatrical figures including P.T. Barnum, Edwin Booth, John Barrymore, and Lillie Langtry.

By the beginning of the 1880s, the focus of sexual entertainment had shifted away from the brothel toward the sort of place the French Madame ran, which “combined saloon and dance hall and invariably featured private, curtained cubicles where patrons could be visited by dancers and waitresses.” Some were highly specialized: one horrendous joint featured cubicles with children. A Bleecker Street establishment was said to house between 100 and 300 men nightly.

The French Madame herself was a “fat, bewhiskered Alsatian woman” who pretended to run a restaurant which only served liquor and black coffee; the cops called her the “French gold mine,” since she paid out an estimated $30,000 in bribes over a period of 6 years. Abortionist Madame Restell, another Tammany revenue source, was able to charge from $500 to $1000 for a consultation, specializing in the mistresses of prominent men, who often put her on retainer to service their “ever-changing roster of sex partners.”

Originally migrating to New York from England in 1920 at age 16, Ann Trow quickly married a quack practitioner, who taught her the rudiments of medicine. She began calling herself Madame Restell, according to Santé, “because of the popular belief that intimate physical matters were best known to the French.”

While maintaining a downtown office, Madame Restell was able to acquire a four-story brownstone on 5th Avenue, outbidding a Catholic Archbishop. Arrested in 1878, she was remanded to the Tombs, “but got out on bail, went home, drew a bath, and slit her throat.”

Like her residence, Marm’s school for crime established on Grand Street in lower Manhattan was not far from police headquarters. Advanced level courses in burglary, safe-cracking, blackmailing and confidence schemes were free to the most astute students who were often offered salaried positions: Marm providing bail and legal defense, if necessary bribing police and judges. This highly respected school for criminals was forced to close shop after 6 years, when Marm discovered the son of a prominent police official had enrolled.

She mentored some of the most famous and successful female criminals, like Black Lena (Kleinschmidt) and the glamorous Sophie Lyons, fine-tuning their pickpocketing and confidence skills: directing them to concentrate on merchandise from the highest class stores that could readily be turned into cash—cashmere, shawls, jewelry, sealskin bags, and especially bolts of silk.

Evading the law, and without paying the hefty percentage of her earnings owed to Marm, Black Lena moved to Hackensack, New Jersey. Posing as the wealthy widow of a South American mining tycoon, she began modeling herself after Marm—throwing expensive dinner parties, and climbing the Hackensack social ladder. Despite her newfound notoriety, she spent two days a week in New York, plying her trade, outside of Marm’s control. Exposed when she showed up to her own dinner party sporting a diamond ring stolen from one of her guests, Lena died in prison in 1886.

It was said Marm treated her most prominent student like a daughter. Young and beautiful, Sophie Lyons came from an aristocracy of criminals. Born Sophie Levy in 1848, her father was a notorious burglar, her mother a renowned pickpocket and shoplifter; her grandfather an infamous burglar in England. Both parents were in jail when waif-like Sophie was 16, and Marm took it upon herself to complete her education.

Sophie is credited as the first to use the “kleptomaniac” defense, on advice of William Howe. She wormed her way out of many tight spots, including Sing Sing! She and her husband (the second of four), Ned Lyons, both in the prison at the same time, managed to break each other out! Moving to Paris with her next husband, she hobnobbed with the upper crust: the couple was rumored to have been guests of the Prince of Wales.

Sophie didn’t learn to read and write until she was 25 but went on to learn four languages. Hiring tutors to help, also with art, music, and history, she passed herself off as a cultured lady of exquisite taste and upbringing, assuming the nom de plume of Madame de Varney--until she was caught trying to lift a diamond necklace from a host’s bedroom during a gala party. Before that, she and her husband pulled off a slew of robberies: once managing to steal $500,000 worth of jewelry and cash in one night.

After spending 3 years in a Detroit jail, Sophie decided to go straight. In 1897, “the Princess of Crime” became one of the first society gossip columnists in the country, writing for the New York World. As a Detroit real estate magnate, owning more than 40 houses, she dedicated the rest of her life to funding prison libraries and orphanages: spending thousands of dollars on food, clothing and rent for the families of prisoners.

Pinkerton detectives were determined to nail Marm. The 1880’s saw Marm and her son Julius staving off as number of indictments involving stolen goods they had fenced. When out on bail, they fled the country.

While under constant surveillance, Marm managed to put her real estate holdings in the name of her daughters, and also made it impossible for the courts to claim the property of her friends who’d put up their bail bonds. Two of them had used their homes as collateral. Marm arranged to have these properties transferred to her daughter then summarily back to the relatives of her friends.

Arriving in Canada, Marm was arrested for smuggling stolen property across the border. Her initial attempts to bribe Canadian police failed, but the owner of the Troy, New York jewelry store who had reported the robbery of diamonds, allegedly worth $4000, was unable to identify the pieces as the stolen goods, and charges were dropped. Paying a duty charge of $614, Marm settled into life in Hamilton.

She bought a two-story, whitewashed house along the main street. Her younger children moved to Hamilton, and sometime in 1886, Marm opened a small dry goods store. A reporter from the National Police Gazette noted all her merchandise came from New York, had no identifying labels, and was selling at incredibly low prices. But Marm and her family were never hampered in Hamilton, having no trouble with the Canadian police.

Even though indictments were hanging over their heads, in less than a year, Marm returned to New York, with her son, Julius, for the funeral of her beloved daughter, Annie: while visiting her married sister there, Annie had caught a cold that turned into pneumonia. Marm’s presence in the city was widely known; she was even interviewed by reporters. After two days, the New York Times declared the fugitives had returned to Canada, “without having been detected by the police.”

The Times described Marm’s appearance at the Temple (she insisted on a Jewish burial, but neither she nor her son went to the cemetery): “The thought of having her favorite child buried without taking a last look at her face touched a tender chord in the heart of the hardened criminal…She showered kiss after kiss on the cheeks of the dead girl and her piteous cries brought tears to the eyes of the persons who witnessed the scene. Several times she attempted to leave the room but she kept returning to the coffin and finally had to be almost carried away.”

As in New York, Fredericka became a visibly active member of the Hamilton community; offering help and charity whenever possible, and regularly attending services at the Shalom Hebrew congregation. Although Conway relates some yearning for New York, he claims Marm became known for her kindness and generosity. When she died in 1894, at age 65, of kidney disease, the obituary notice in the Hamilton Spectator while mentioning her criminal past, called her “a woman of kindly disposition, broad sympathies, and large intelligence.”

Her body was returned to New York City for burial at the family plot in Union Fields cemetery in Queens. A huge crowd of mourners, including former neighbors and friends, legitimate businessmen, police, judges, reporters, curiosity seekers, and a score of well-known criminals, all turned out to pay their final respects to the “Queen of Thieves.”

* * *

Coda: for the children

Oddly, the story of Marm Mandelbaum can be found in a children’s book: Guided Reading Levels, Ages 9 – 12.

Written by Tom McCarthy, Daring Heists: Real Tales of Sensational Robberies and Robbers is part of Nomad Press’ “Mystery & Mayhem” series, all of which appear to have been written by the same author. Most of the 5 Real Tales here involve victorious thieves whom McCarthy clearly admires (the exception concerns the theft of artifacts from the National Museum of Anthropology in Mexico City). His Introduction states: “The heists in this book required skill and ambition and intelligence. Bravery, too, because the thieves knew if they were caught, they’d spend a lot of time in prison.”

McCarthy’s homage to Marm, “She might have been the smartest criminal in all of New York City and maybe even the United States” is followed by the question, “How did she get like that?” He rather briefly goes into her life as “a poor immigrant with no money,” quickly seguing to his leitmotif: “Even the air smelled different in America—it smelled of hope.”

Marm could get money for anything, since thieves “from across the entire United States sought her out when they wanted to sell stolen diamond rings and ruby necklaces, silver candelabras, or ornate chandeliers. One day she even bought a herd of stolen sheep, from halfway across the country in Chicago.” (Luc Santé tells us it was actually Ephraim “Old” Snow who received this errant flock.)

McCarthy’s tale is rather ambiguous when it comes to Marm’s stature in the community—both literally and figuratively. He describes her moving onto the “bustling sidewalk…swept along like a bobbing twig in a fast-moving stream.” Noting her height and weight, he adds, “so seeing her being moved quickly along the sidewalk was something to behold!”

However, he asserts Marm’s “magic” was her ability to “blend in with her surroundings despite her size and the flamboyant hats she loved to wear.” Stating (in sharp contradiction to most other accounts), “her round face with full cheeks…made her look almost angelic.”

Counting on her appearance being deceiving, Marm “figured that the fewer the people who knew what she was really up to, the better. That was especially true about the police.” Elsewhere, he assumes the police were entirely aware of, and in cahoots with, Marm: the district attorney, for instance, “knew there were very few police and judges he could trust—so many of them were on her payroll!”

(Would a perspicacious 9-12-year-old notice this intriguing contradiction, thereby diving precipitously into adulthood?)

Enter the un-bribable Pinkertons! Described as “like dogs with bones when they got wind of a criminal who needed to be caught,” still, they couldn’t prevent Marm from skipping to Canada. There she arranged to meet several of her gang members, bringing “more than $1 million from stash of stolen money.”

This children’s book makes no mention of daughter Annie’s death—or, for that matter, of the infant Bessie’s. We do read, “Marm Mandelbaum lived well in Hamilton, but she was homesick…she died in 1895, a sad woman.” In the closing paragraphs, her body is returned for burial where “throngs of grieving supporters expressed their love and sadness” at her death.

Apparently, though, “not everyone was sad.” As her funeral procession worked its way down Clinton Street, “more than a dozen of her former students worked their way up the street. They smiled as they picked the pockets of the unsuspecting and curious mourners.”

And McCarthy’s finale: “Marm would have been very proud.”

A version of this piece first appeared in the San Diego Free Press

Mel Freilicher retired from some 4 decades of teaching in UCSD's Lit. Dept./ writing program. He was publisher and co-editor of Crawl Out Your Window magazine (1974-89), a journal of the experimental literature and visual arts of the San Diego/Tijuana region. He's been writing for quite some time. He is the author of The Unmaking of Americans: 7 Lives, Encyclopedia of Rebels, and American Cream, all on San Diego City Works Press.