The 50s: Era of Business Unionism

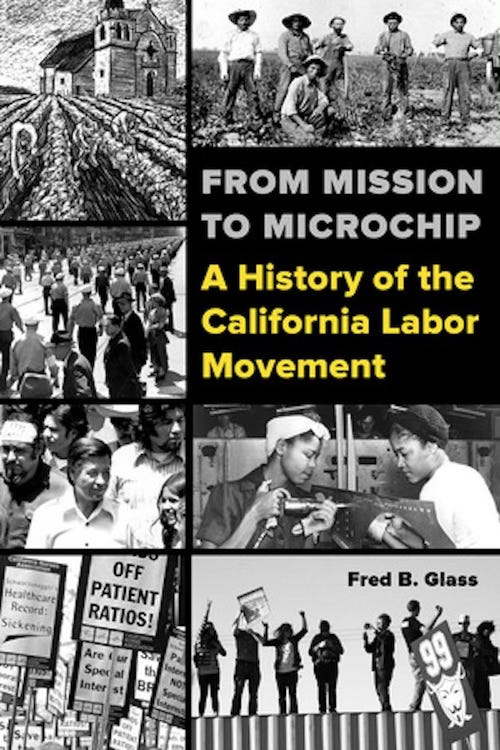

The Labor History Corner--an excerpt from "From Mission to Microchip: A History of the California Labor Movement" By Fred Glass

A version of this article appeared on the California Labor Federation California Labor History website. You can buy From Mission to Microchip: A History of the California Labor Movement from the University of California Press.

As California’s working class approached its hundredth anniversary in 1950 many of its goals had been achieved, and it seemed as if it was entering the next century in a position of unassailable strength. More of the state’s population held union cards than ever before. In manufacturing, where much of the membership gains and power had come from during the previous fifteen years, over half of the workers were affiliated with organized labor. Despite the closure of large shipyards in the Bay Area and aircraft production in the south after World War II, California’s economy continued to expand. This was due to weak competition from war-ravaged Europe, and the beginning of the Cold War, which encouraged the continuation of large-scale weapons production on a permanent basis. By the late 1950s legislators from other states were complaining that more of the federal government’s aerospace dollars were flowing to California than to the rest of the country combined.

California was strategically placed—both geographically and in terms of its industrial capacity—to play a key role in the United States’ newfound dominance in the world economy. After fifteen long years of Depression and War, of migration away from Dust Bowls and southern racism, the promise of the American Dream was fulfilled for much of California’s working population. There were jobs for nearly everybody who wanted to work, with automobiles and home ownership for almost everyone, along with beach privileges on the weekends.

Put another way, the working class was finally able to become “middle class.” Through collective bargaining and legislation, health and retirement benefits became a standard part of the compensation paid by employers to workers. The children of union members went to college in unprecedented numbers, thanks to the labor-backed GI Bill, passed near the end of World War II. The strength of organized labor lent working people the ability to rise from the economic uncertainties that had plagued them since the Industrial Revolution. Although employment options were skewed by racist and sexist job discrimination, most workers and their families attained a level of comfort and security in the 1950s only dreamt of for generations.

The material benefits came at a political cost. The period also featured a “red scare,” similar to that of the post World War I era. Left wing unionists, whether they were Hollywood screenwriters and actors, leaders of the International Longshoremen’s and Warehousemen’s Union, sewing machine operators in the Los Angeles garment district, or machinists in security-sensitive missile factories, faced congressional hearings, employment blacklists, loyalty oaths, and new laws curtailing civil liberties (some of which were later determined to be unconstitutional). The CIO expelled eleven unions suspected of control by Communists.

The California AFL and CIO turned increasingly to working within the political system. The rank and file, from representing an independent power capable of settling differences with management by shutting down or sitting down in the workplace, came to be viewed by the new generation of labor leaders as citizen-voters who enforced election day discipline on public officials. This approach to labor politics seemed to work.

By late 1958, after a successful fight against a right-to-work-for-less state ballot measure had built greater trust, the AFL and CIO in California merged. The differences between them, so crucial to the explosion of organizing in the 30s, had been put to rest. The two federations agreed that cooperation made more sense than wasting time and money fighting one another.

Even persistent problems, like inequitable treatment of racial minorities in the workplace, seemed, within a growing economy, solvable. The United Auto Workers bargained for plant-wide seniority rules in the South Gate GM factory, which put a stop to minority workers staying stuck in the hardest and dirtiest work, as they had due to the prior system of seniority by department. And when the Fair Employment Practices Act passed in 1959 after more than a decade of coalition building between unions, civil rights organizations and religious and community groups—which made discrimination in hiring and promotion on the basis of race illegal—the political approach seemed further vindicated.

Despite these successes, it would pay to remember one important point: that the ability of workers and their families in the post-World War II period to become “middle class” and lead “the good life” had depended precisely on acting, together, in solidarity, in the previous decades, as a working class. This insight, shared by millions of workers before the 50s, eroded in collective memory under the dual impact of prosperity and cold war politics. With times prosperous and unemployment low, militant methods of expressing union power, like the general strikes in San Francisco in 1934 and Oakland in 1946, seemed increasingly remote and obsolete.

An affluent society was finally delivering on the deferred promise of the American dream for working people—so long as they didn’t mind a few limitations on their civil liberties, accepted the tradeoffs of a rising tide economy based on permanent preparedness for war, and chose not to notice if perhaps not everyone was on the boat.

Fred Glass is the author of From Mission to Microchip: A History of the California Labor Movement (UC Press, 2016) and a former member of the State Committee of California DSA

Stay tuned for the next installment…