Highlander: No Ordinary School by John M. Glen on the University of Tennessee Press (Second edition) 1996

By Mel Freilicher

1.

I had known Martin Luther King, Jr. and Rosa Parks both attended Highlander Folk School workshops, where curriculum was derived from vital elements of their students’ daily lives. Also, “We Shall Overcome” and other church songs underwent alterations there to become crucial anthems of the civil rights movement. But that’s all I knew about this remarkable school, improbably located in one of the poorest counties of Tennessee, near the small Cumberland Plateau town of Monteagle.

Opened in 1932, and operating for 30 years, Highlander, John Glen writes, “served as a community folk school, a training center for southern industrial labor and farmers unions, and a major meeting place for black and white civil rights leaders.” Its stated function was to educate these leaders “for a new social order…enriching the indigenous culture of the mountains.” At its heart, “was a belief in the power of education based on the experiences of the poor of Appalachia to change society.”

During the early and mid-1930s, staff members struggled to define Highlander’s role in the emerging southern labor movement as well as in the local community. At first consisting of “relatively traditional courses for a painfully small number of students,” Glen writes, “The most striking characteristic of the Highlander Folk School’s work between 1932 and 1937 was the contrast between its ambitious objectives and its limited achievement.”

Highlander provided relief to the families of striking United Mine Workers, gathered data on living conditions of the workers, compiled reports and conducted study sessions on union and strike activities. Although this strike, and a spontaneous one by local woodcutters which HFS supported, were lost, such efforts revitalized class sessions: using union and work conditions as the basis of much of their curriculum and bringing into workshops numbers of seasoned union activists.

HFS educators believed potential labor leaders could be educated to help fellow workers if they had a chance to discuss their situations, discover and act upon new ideas. As a result, Highlander’s approach laid the basis for larger, more influential programs. Residence students later became organizers and officers for mine and textile workers unions, held their own classes for workers, and returned to Highlander as advisers and teachers. The community program led to a greater acceptance of the school in the Monteagle area.

In 1935, Highlander’s largest and most effective extension undertaking was a union organizing and education campaign among WPA relief workers in Grundy County who earned $19.20 a month, the lowest wage rate in the Southeast. Although federal orders clearly divided workers into skilled, intermediate, and unskilled wage earners, because the entire county was categorized as agricultural by local officials unsympathetic to New Deal goals, everyone was being paid at the unskilled level. This was only remedied after 2 years of struggle.

By 1937, Highlander had developed summer and winter residence courses, year-round extension work, and a program of cooperatives, recreational and cultural events for county residents. That year, about 160 students attended residence terms, over 1550 had been reached via extension classes, and at least another 1,000 were present during special institutes. Such numbers, Glen suggests, “hardly indicate that Highlander had become a sweeping success after five years of operation.”

Despite repeated praise by clergymen, union leaders and others, the Folk School was vociferously denounced by some prominent locals, American Legionnaires, and evangelist Billy Sunday as “a thoroughly communistic enterprise.” Intimidating Highlanders was generally understood to be the purpose of the statewide rally the American Legion held in Monteagle in 1935.

The night before the rally, a large, bronze American eagle perched on a concrete and rock base at a motel in town was dynamited, immediately arousing suspicion against the school. The next day, with most of the Highlander staff on a field trip to Alabama, several hundred legionnaires gathered to paint stars and stripes on the eagle’s pedestal and to hear speakers rail against the communist menace in America.

“Monteagle citizens were largely indifferent to the Legion’s presence,” Glen reports; some stood guard at the school. The Chattanooga News, ridiculing their rally, printed pictures of Highlander residents standing in their garden, “fomenting political unrest amid bean bug life.” Ironically, though, this same paper sparked a major controversy 2 years later.

An article by the chairman of the Chattanooga American Legion claimed a state employee posing as a newspaper reporter investigated and found the school be a dangerous institution—featuring drunkenness, immorality, and singing of the Communist “Internationale.” The Chattanooga Free Press joined the attack the next day.

HFS leaders quickly decided to elicit “all the labor and liberal support” possible, to make the News editor “pretty damn sick” of the controversy. Throughout February 1937, Norman Thomas, six-time presidential candidate for the Socialist Party of America, and Reinhold Neibuhr, renowned theologian, as well as TVA employees, clergymen, labor organizations and others bombarded the editor with letters which he initially refused to print.

Most significant to Highlander staff was the petition signed by over four hundred county residents expressing their appreciation of the faculty’s work on their behalf. Eventually, the editor beseeched the school to call off the campaign.

Achieving a level of proficiency just as New Deal legislation and the formation of the CIO were stimulating Southern labor unions, one union official observed the school promised to be of “inestimable value”—providing workers in the South with ”an excellent opportunity to prepare themselves for the battle just ahead.”

CIO leaders asked Highlander to join their organizing drive for the entire region in 1937. Over the next decade, staff helped unionize textile workers in Tennessee, North and South Carolina, directed large-scale labor education programs in eleven southern states, and developed a residential program to build a broad-based, racially integrated and politically active labor movement.

In his book-length dialogue with Paulo Freire, We Make the Road by Walking, Myles Horton, the founder of Highlander, clarifies these goals: “My idea was to help people choose to change society and to be with the people who were in a position to do that…I wasn’t interested in mass education like a schooling system. I was interested in experimenting with ways of working with emerging community leaders, to try to help those people get a vision and some understanding of how you came about realizing that vision so they could go back into their communities and spread their ideas.”

As a result, “It wasn’t surprising to us that we were not considered educators…Practically no educational institutions invited any of us to talk about education. We were invited to talk about organizing, civil rights, international problems—but education, no.” The change came, Horton claims, “after the Brazilian government made a contribution of Paulo Freire to the United States by kicking him out of Brazil. He came to Harvard…As far as I was concerned, his greatest contribution [here] was to get people in academic circles to recognize there’s such a thing as experiential education.”

The late 1940s and early ‘50s were transition years for Highlander. The declining militancy of the CIO eroded the school’s relationship with organized labor. Unlike the AFL, from the beginning communists had been prominent in the CIO, accepted for their organizing skills and commitment to industrial unionism. But this issue sparked bitter factional debates.

Delegates to the 1949 CIO convention, charging left wing unions put the interests of the Communist Party above those of the union, voted to expel the United Electrical, Radio, and Machine Workers and the Farm Equipment Workers. By the mid-1950s, unions claiming to represent over one million members had been driven out of the CIO.

Since opening its doors, in theory and in limited practice, Highlander had welcomed black southerners, believing in the necessity of cooperation among black and white workers. Charles Johnson, a sociologist at Fisk, visited the school during its first year. Yet in March 1934, the staff reluctantly decided not to invite a group of black students to the school, fearing “the harm it would do in the community would more than offset any sort of value.”

Shortly afterwards, J. Herman Daves, a black professor in Knoxville, was asked to join the faculty as a part-time instructor. Reaction came swiftly. Guards had to be posted at night when local opponents threatened to dynamite Highlander. Not until ten years later did forty black and white members of the United Auto Workers attend the first integrated workshop there.

Beginning in 1953, the Highlander staff launched a series of interracial workshops for community leaders and students: initially centering on public school desegregation and gradually growing to encompass the problems of communitywide integration. Workshop participants were given opportunities to express their ideas and feelings, to lead discussion groups, role play, and practice parliamentary procedures in an atmosphere of acceptance.

Interracial living fostered personal bonds rather quickly. Workshop discussions continued in shared rooms, during meals, and over chores like washing the dishes. When 56 year-old educator and activist, Septima Clark, enrolled in a workshop, she said, “I was surprised to learn that white women would sleep in the same room that I slept in…and it was really strange, very much so, to be eating at the same table with them.”

Rosa Parks attended a Highlander workshop on integration in 1955. One of the few black high school graduates in Montgomery, she’d joined her local NAACP chapter during WWII and served as secretary and adviser to its youth auxiliary. Creating quite a stir in 1948, Parks had taken the youth chapter to see the Freedom Train exhibit of Americana and related historical artifacts. She began receiving threatening phone calls before the train pulled out of Montgomery.

Langston Hughes had written a critical poem, “Freedom Train,” famously recorded by Paul Robeson, describing the train, sponsored by the federal government, and heralded as a lesson in democracy, passing through the segregated South with black and white passengers riding in separate cars. Facing an international public relations backlash, in 1947, only two weeks before it was scheduled to depart, the Truman administration announced the desegregation of the train.

Having attended that same workshop, Septima remembered Rosa Parks as timid and painfully shy: reluctant to tell the Freedom Train story, until a United Nations representative at the workshop promised her assistance should whites retaliate. As Ms. Parks commented years later, “This was the first time in my life I had lived in an atmosphere of complete equality with the members of the other race.”

During the Montgomery bus boycott, Highlander staff’s immediate concern was to find a source of financial support for Rosa Parks who lost her job; her husband, a barber, lost customers; both her mother and husband had fallen ill; her rent was raised; demands of the boycott on her time and energies made it hard to earn a living. Providing moral and some financial support, HFS faculty offered Rosa a job as speaker and recruiter. After a few activities there, her family moved to Detroit where she eventually joined the staff of Congressman Conyers.

In the ‘50s, Septima Clark took a series of administrative jobs with Highlander. Designing the Citizenship School program, Clark rightly predicted adult literacy training would add African Americans to the voting rolls. She’d already begun a voter registration drive on Johns Island, site of her first teaching job; working with the local Citizens Clubs, comprised of small landowners, provided a buffer against white reprisals.

Her first reader for those classes (which included some adolescents) contained a history of Highlander; sections of the state’s laws and its constitution; a copy of a registration certificate; information on the Democratic and Republican Parties; a section on “Taxes You Must Pay in South Carolina”; a description of social security and how to claim benefits; a list of health clinics in Charleston County; instructions on how to address elected officials; and blank mail order and money order forms.

By the time classes began in 1958, the expansion of three additional schools in South Carolina forced Horton and Clark to formalize their pedagogical procedures. All Citizenship classes would be taught by African Americans respected in their communities, not necessarily teachers but who “could read well aloud and write legibly.”

Required to attend a five-day training workshop at Highlander and follow up sessions, Citizenship School teachers were also expected to do research in their own communities: for instance, knowing the names of elected officials, location and hours of the voter registration and social security offices as well as available health services.

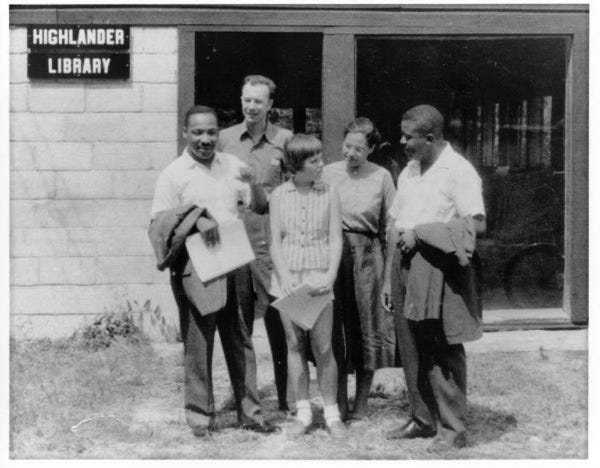

The mid ‘50s was a very heady period for Highlander. The centerpiece of their 1957 residence program occurred on Labor Day weekend when about 180 people gathered to celebrate the school’s 25 years of service. Former staff member, John B. Thompson, now dean of the Rockefeller Memorial Chapel at the University of Chicago, served as director of the seminar on future directions for integration of religious groups, education, trade unions, and civil organizations. The anniversary was celebrated with square dances and group singing led by Pete Seeger. Martin Luther King, Jr. gave an inspiring culminating speech.

Insidiously, the segregationist governor of Georgia used state tax funds to establish the Commission on Education which hired a photographer to infiltrate the anniversary celebration. Martin Luther King, Jr. was photographed with Abner Berry, a correspondent for the Communist Party’s Daily Worker. Additional photos showed blacks and whites eating, swimming, and dancing with one another, and huddling together, allegedly to discuss integration.

One month later, the Georgia Commission released 250,000 copies of a four-page photo spread, Highlander Folk School: Communist Training Center, Monteagle, Tenn.; the Klan reprinted an estimated 1,000,000 more. By the mid ‘60s, billboards reproducing the photo appeared across the region with the words, “Martin Luther King at Communist Training School.”

This assault came as part of a well-organized right-wing attack on Highlander. An “expose” by the Nashville Tennessean—HFS was “a center, if not the center for the spreading of Communist doctrine in 13 southeastern states”—adversely affected the school’s fundraising efforts for several years. Rumors arose of Highlander as a free love commune with a library full of Communist literature; and one leader was said to not only be a Party member but a convicted criminal as well.

In 1940, House Committee on Un-American Activities chairman, Martin Dies, announced he had received a large amount of material on Highlander in connection with a probe of alleged radical activities in the South. The most thorough defamation came that November with the appearance of The Fifth Column in the South, a pamphlet by Joseph P. Kamp, a well-known pro-Fascist, anti-Semitic, anti-labor propagandist.

Myles Horton had taken the stand in the school’s defense in a 1953 McCarthy hearing and ended up being dragged out of the chamber following his attempt to read a statement on civil rights by President Eisenhower. In spring of 1954, Mississippi Senator James O. Eastland opened an inquiry.

A special legislative committee of the Tennessee General Assembly started an investigation of HFS in 1959 with two witnesses testifying the school “was operated out of Moscow”—though admittedly they’d never set foot on the property. The Committee recommended the Attorney General inaugurate a suit to revoke Highlander’s charter. A search turned up liquor at Horton’s home on the periphery of the campus (technically, not covered by the warrant) and he and Septima (who was a teetotaler) were arrested, the first time in her 61 years.

In the subsequent hearing, state witnesses provided titillating testimony, swearing they’d seen nude, interracial couples having sex in cabins and on the front lawn, or walking into the nearby woods, “locked in each other’s arms and engaging in many other practices of lewd and lascivious character.” The defense attorney called their credibility into question. Two of the witnesses had gone to reform school, one served a prison term, and one had been jailed more than thirty times for drunkenness.

The Circuit Court judge ordered a temporary padlock placed on the school’s main building: ruling the state had failed to prove HFS was a den of moral iniquity, but they had broken a state law regarding the distribution of alcohol without a license.

On February 16, 1960, the school’s charter was revoked. The next year the U.S. Supreme Court declined to hear the case, and the Highlander Folk School ceased to exist. Expecting as much, Myles Horton had already obtained a charter for the Highlander Research and Education Center, moving his operations to Knoxville. As he maintained from the beginning, “Highlander is an idea. You can’t kill it and you can’t close it.”

When state repression forced Highlander to transfer the Citizenship education classes to the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) in 1961, Clark helped make the program a cornerstone of their mobilization strategy.

“In truth,” Katherine Charron, Septima Clark’s biographer, writes, “the Citizenship Schools had expanded so much that they had become unwieldy for Highlander to manage.” She quotes Myles: “’We weren’t interested in administering a running program, we were just interested in developing it…We wanted to get out if it and let other people run it.’”

2.

“The Highlander Folk School was the product of a personal and intellectual odyssey by its cofounder, Myles Falls Horton” –the opening sentence of John Glen’s thorough study.

Born in Savannah, Tennessee in 1905, to impoverished former schoolteachers, Myles’ parents, of Scotch-Irish descent, were Calvinists who imparted both the necessity of education and the concept of social service, by aiding whites and blacks less fortunate than themselves with food and clothing.

Myles was an avid reader his whole life, but books were hard to come by. Entering Cumberland University in Lebanon, Tennessee, intending to pursue some form of religious education, he majored in English literature: especially focusing on Shelley’s idealism and romantic defiance of authority, and John Stuart Mill’s arguments that individuals should assume responsibility for acting on their convictions. He organized fellow freshmen against the traditional hazing rites, and refused to join a fraternity, a school requirement.

Horton supported John Scopes, being tried in Dayton, Ohio, for teaching evolution. As President of the Cumberland YMCA, attending a conference in 1927 in Nashville, he mingled with people of different races—only to confront the fact that he could not take a Chinese woman into a restaurant or public library with a black man.

Back in college, he listened to a lecture by a member of the school’s board of trustees--arguing wage earners made a mistake when they tried to unionize. Incensed, Myles visited the local textile mill, talking to workers about the necessity of exercising their rights. The school threatened to expel him if he did that again.

”The most decisive education Horton received,” came, according to Glen, when he directed a Bible school for the Presbyterian Church, U.S.A. Having spent two previous summers in similar work, and dissatisfied with its limited usefulness, Horton invited the parents of the school children to attend informal meetings at the church in the evening. To his surprise, he found adults eager to learn about farming, employment in textile mills, public health, cooperatives and the general economic conditions of their region.

Under the auspices of the YMCA, Myles traveled to a number of schools and colleges hoping to find institutional support for the kind of educational program he had in mind. He began to realize he would be unable to work within any “regular school,” since none took an interest in the attitudes and needs of the people in the southern mountains.

Luckily, his affiliations in the Presbyterian Church led him to the home of Abram Nightingale, a Congregationalist minister who influenced Horton to immerse himself in books about Tennessee and southern history, the culture and problems of society in southern Appalachia, and the place of morality in a modern capitalistic society.

In 1929, bluntly telling Myles he needed more formal education, Nightingale obtained an application for him to take courses at Union Theological Seminary in New York City and gave him a book by a professor of ethics there: a “spirited critique” of the failures of capitalism resulting in extremes of luxury and poverty.

With no intention of becoming a minister or obtaining a degree, Myles took a variety of classes at the Seminary while working at a boys’ club in the Hell’s Kitchen neighborhood, visiting settlement houses, serving as a volunteer organizer in an International Ladies’ Garment Workers Union strike in New York, and observing a bitter textile strike in Marion, North Carolina. Subsequently visiting Brookwood Labor College, and what remained of the cooperative experiments at the Oneida Colony in upstate New York, New Harmony, Indiana, and others.

At the Seminary, the most powerful influence on Horton was Reinhold Niebuhr, prolific author, leader in the newly organized Fellowship of Socialist Churchmen, member of the pacifist Fellowship of Reconciliation. Overpowered by the complexity and passion of “Reinie’s” ideas, Myles planned to drop the class until Niebuhr dissuaded him. The two men developed a friendship that was to last the next four decades.

Horton was drawn to Niebuhr’s attacks on corporate capitalism and the flaccid idealism of the social gospel, his clear commitment to the interests of the working class, concern with the relationship between spiritual values and material welfare, and his call for new forms of education. Myles told Paolo Freire what Niebuhr had clarified for him: “It doesn’t make a great deal of difference what the people are; if they’re in the system, they’re going to function like the system dictates they function. From then on I’ve been more concerned with structural changes than with changing hearts of people.”

Turning from theology to sociology, in 1930 Myles began attending classes at the University of Chicago’s prestigious Graduate School of Sociology. From Robert E. Parks and other professors he learned “combining techniques of accurate observation” with personal involvement in a community could enable him, as he wrote, “to detect the real desires of the people and plan his work in the light of this discovery.”

In Chicago, Myles was president of a local Socialist Club and Midwest representative for the League of Industrial Democracy. Visiting Hull House on several occasions, he discussed his embryonic ideas with Jane Addams who remarked his proposed school resembled “a rural settlement house.”

A Danish-born Lutheran minister who’d opened his church to university students for square dancing had formerly been a student and teacher at folk schools in his homeland; he suggested the Tennessean visit there to study potential models for his own endeavors. Horton spent the rest of that spring learning more about the culture, language, and folk schools of Denmark.

Undeterred by offers of a graduate assistantship from Professor Parks, a position as principal of an academy in Tennessee, even by his parents’ financial needs, and the pleas of radical friends to stay home and fight for change, Horton arrived in Denmark in September 1931 with little money and only a slight understanding of Danish. Spending the next several months traveling, observing, talking to folk school students and teachers, when his language skills improved, he began giving lectures to civic clubs, labor unions, and educational groups.

Although the original purpose of Danish folk schools was to awaken and develop patriotism and civic responsibility among the nation’s long-oppressed peasantry, by the late 1920s they were widely credited with improvements in agricultural practices, growth of intellectual activity and political participation within rural Denmark. Horton most admired the newer, urban folk schools for industrial workers which addressed the specific problems of workers and farmers while maintaining a commitment to far-reaching social and economic reform.

Back home, outlining his plans to Reinhold Neibuhr, Horton secured his aid in raising money to establish a school. With an advisory board that also included Sherwood Eddy, secretary of the international YMCA, and Norman Thomas, Socialist Party leader, Horton raised over $1300, receiving the support of such luminaries as John Dewey, Roger Baldwin of the American Civil Liberties Union, and Frank Graham, president of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

While fundraising, Horton began searching for teachers and a suitable location for the school. Two of his former Seminary classmates agreed to join him after they finished graduate work; James A. Dombrowski stayed for nearly a decade. Horton was advised to meet Don West whose background was quite similar to his own, and who also wanted to establish a folk school in Appalachia.

Born in rural north Georgia, West had worked his way through Lincoln Memorial University, where he’d been president of the student YMCA. Entering Vanderbilt University in 1928, West developed a keen interest in folk school education, spending a year in Denmark before returning to Vanderbilt to obtain his Bachelor of Divinity degree. On first meeting, Myles found West, then pastor of a small Congregationalist church, to be a “mountain socialist…growing more revolutionary by the day.”

West had learned Lilian Johnson of nearby Monteagle, Tennessee was about to retire, and wanted to turn over her farm to someone who would use it as a community project. Born into a wealthy Memphis banking and mercantile family in 1864, Lilian earned a Ph.D. at Cornell University and went on to a distinguished career as an educator and advocate of agricultural cooperatives, temperance, women’s suffrage; she established a women’s college in the South with a curriculum as broad as that of male-dominated universities.

Mrs. Johnson had built a large house as a community and educational center for both children and adults in 1915: promoting numerous programs over the next 17 years, including classes to teach children to read, and night school for adults. However, Glen states,” Most of Johnson’s well-meaning efforts failed, largely because her condescending view of the community prevented her from ever understanding why her neighbors would not completely adopt her ideas.”

Following a series of meetings, she made a simple agreement with Horton and West. The two men could use her property as long as they ran the school themselves, developed good relations with the community, and achieved tangible results. If at the end of one year, Johnson wasn’t satisfied, they would have to go. On November 1, 1932, the Highlander Folk School opened for business.

Visiting the school almost three years later, Lilian Johnson concluded it had become an acceptable part of the community and deeded the house and forty acres of land to Highlander’s directors. She never quite understood why Highlander had become involved with labor unions, and worried about its reputation as a den of immoral square dancing and communism. But Lilian was certain Horton had never been “communistic,” and much of the criticism had been brought on by Don West--not only “too radical,” but “not so balanced as he should have been.”

Among the eight students attending the two-month, 1935 winter session was Zilphia Mae Johnson, a quiet, sensitive, and talented woman of Spanish and Indian blood whose father, an Arkansas coal mine owner, had forced her to leave home because of her “revolutionary Christian attitudes.” Determined to use her musical and dramatic abilities in “some field of radical activity,” Zilphia had become a devoted follower of a Presbyterian minister who arranged for her to go to Highlander with the idea of learning some fundamentals of the labor movement.

“The ardor Myles had for Zilphia,” Glen comments, “was as intense as his commitment to Highlander.” His marriage to “the girl I had been waiting for” would last till Zilphia died in 1956 from accidentally drinking typewriter cleaning fluid. Music became a vital part of Highlander’s program almost as soon as she arrived. Zilphia encouraged students to share songs out of their own experience, using a piano or accordion to help them write music or lyrics and to lead groups in singing them.

Music and folk dancing were viewed as forms of both entertainment and education. Zilphia Horton and others integrated Highlander’s cultural program into the curriculum and made the school truly attractive to the community and workers in the region. The cultural program gained national and even international notice when the British Broadcasting Company presented a performance from HFS in 1937. As the Knoxville News-Sentinel reported, the ballads and spirituals sung by Zilphia, Lee Hays and others were “the genuine article in Southern Highland music.”

Lee Hays and Zilphia had first met as fellow students at the College of the Ozarks, where students were allowed to work in lieu of tuition. Hays went on to become a founding member, with Pete Seeger and Woody Guthrie, of the famous Almanac Singers, a somewhat fluid group which later included Josh White, Cisco Houston, and Bess Lomax Hawes. Then with Pete Seeger, Lee Hays joined the influential, soon-to-be blacklisted Weavers.

In 1938, Zilphia Horton developed a highly effective and popular approach to teaching and disseminating songs. By skillfully changing a few lines to familiar tunes, she turned hymns, ballads, and popular songs into forceful expressions of protest. Most notably, a Protestant hymn, “I Shall Not Be Moved,” became the celebrated labor song “We Shall Not Be Moved” (further popularized by Hays with the Almanac Singers). “Keep Your Eyes on the Prize” and “This Little Light of Mine” were also metamorphosed into “freedom songs” by Zilphia, Guy Carawan, and colleagues.

“We Shall Overcome” began as a religious folk song that evolved into a formal Baptist hymn. Then during a 1945 strike, members of a food and tobacco workers union in Charleston changed its lyrics to maintain morale on the picket line. Slowing the tempo, Zilphia added new verses, began teaching it to HFS students, and singing it at various gatherings. Learning the song from Zilphia, Pete Seeger revised it further.

Under her direction, students sang at union meetings, workers’ education conferences, rallies, and strikes throughout the region. The “real musical merit” of folk songs, Zilphia wrote, was not their form but “the way they expressed the struggles of working people.” She published at least ten songbooks, and mimeographed thousands of song sheets for residence sessions and picket lines.

Zilphia’s drama classes became one of the high points of the curriculum. After her marriage, she studied workers’ theater at the New Theatre School in New York, and returned to teach dramatics, as well as the rationale behind workers’ theater.

In one summer residence, students prepared a play about a strike, held a mock AFL conference, worked on mass recitations and songs, and presented a program to union audiences in Chattanooga, Knoxville, Atlanta, and to TVA workers. Under Zilphia’s direction, emphasis shifted the focus of plays toward educating those who participated in them rather than their audiences.

Highlander sponsored many diverse activities in the late ‘30s: among other guest lecturers, a writers’ workshop featured Sherwood Anderson. The school’s dramatics program gained tremendous impetus following the 1938 premiere of a documentary, People of the Cumberland, directed by Elia Kazan and shown at HFS, union meetings, and to Eleanor Roosevelt at the White House. After the outbreak of WWII, student plays concerned the poll tax and the role of organized labor in the war.

Work camps combined manual labor and educational experiences: during the summer of 1938, the staff turned the school over to the American Friends Service Committee for a two-month session. A series of junior union camps, another Highlander project, encouraged the children of union members to participate in running the camp by electing officers and forming committees to oversee various projects.

The most prominent southern alliance in the late 1930s and 1940s was the Southern Conference for Human Welfare (SCHW). Myles and Zilphia attended their first convention in Birmingham in 1938, along with Supreme Court Justice Hugo Black, Eleanor Roosevelt, black college presidents, a sizable group of black and white CIO officials, a smaller contingent of AFL and railroad brotherhood representatives, two dozen Socialists, and a handful of Communist Party members.

Highlander assisted in their fight against the Tennessee poll tax. But, Glen states, “for most of its existence SCHW’s militant reputation and allegations of Communist influence hindered its efforts” for Southern reform. In 1940 Eleanor Roosevelt, meeting with a group from Highlander at the SCHW convention, donated the first of several $100 scholarships to the school.

Later that year, the Chattanooga News-Free Press reproduced a copy of one of those checks to bolster its allegation of the First Lady financing subversive activities. The president of the bank, who was also secretary of the Tennessee Consolidated Coal Company, insisted he’d done nothing unethical in publicizing Highlander’s bank records since the school was “against the government.”

Reprinting Eleanor Roosevelt’s check on the inside front cover, quoting liberally from the Tennessean series on Highlander, and distorting the meaning of some of their own literature, he branded the school a “training center for Communist agitators,” and “a fountain head of propaganda for revolution.” Although his pamphlet cost 25 cents, many copies were distributed free throughout Grundy County: financed, HFS staff members had no doubt, by Consolidated Coal.

Dembrowski and colleagues outlined Highlander’s work to Governor Prentice Cooper and at public meetings in Sewanee and Nashville. A timely and powerful public relations victory came in November when the third national convention of the CIO, representing four million workers, unanimously approved a resolution endorsing the school and condemning efforts to “discredit and defame” it. HFS had already received the unanimous endorsement of the Tennessee State Industrial Union Council, and commendation by its president, John L. Lewis.

Despite threats, the Highlander benefit concert in Washington D.C. that December was a smashing financial success and brought about a decisive shift in Highlander’s struggles with the antagonistic Grundy County crusaders. As one historian of the school remarked, the concert’s sponsors “read like a Who’s Who of the New Deal and organized labor,” including Justice Hugo Black, cabinet members, congressmen, administrators of major federal agencies, and other prominent persons.

The audience heard a poetry reading from Archibald MacLeish, then Librarian of Congress; a ballad performed by the Washington Choral Society and the Howard University Glee Club; and a collection of folk, blues and workers ballads sung by Zilphia Horton and famed blues singer Huddie “Leadbelly” Ledbetter. National attention given the Washington concert markedly improved public perception of Highlander as a legitimate institution.

John Glen’s detailed study offers many other tales of Highlander’s activities until the school was forced to close in 1961. Of particular interest are their conferences following the first sit-in at an F.W. Woolworth lunch counter on February 1, 1960, held by four black students from North Carolina Agricultural and Technical College. Beginning a shift of tactics from a largely legalistic approach to direct action: transforming the civil rights movement in a decade of protests.

Two months later, Ella Baker, executive director of SCLC, initiated the founding conference of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) seeking to bring student leaders together in an organization that would keep their protest active, nonviolent, and, significantly, free of adult control. This conference attracted more than 120 black college and high school students from twelve southern states and D.C., as well as a dozen southern white students, delegates from northern and border state colleges, and representatives of thirteen other groups, including Highlander.

SNCC was encouraging white students to work with them, so Highlander’s next workshop, held in May 1960, outlined “The Place of the White Southerner in the Current Struggle for Justice.” (Six years later, Stokley Carmichael was elected national chairman of SNCC: having no faith in the theory of nonviolent resistance, he turned sharply radical, and made it clear white members, once actively recruited, were no longer welcome.)

Black activists, like Ella Baker and the Reverend Fred S. Shuttlesworth, stressed the need for whites themselves to break down barriers. Workshop groups among thirty-six whites and twenty-eight blacks explored how they, collectively, could pressure businessmen and politicians to end segregation and black disenfranchisement, as long as whites could avoid “the old pattern that has often prevailed even in liberal interracial organizations—that of white domination.”

Highlander held two more workshops designed to examine the role white college students could take in the protests. In April 1961, 87 individuals, mainly students, met to consider the future direction of the movement. Among the participants were Ella Baker, Bernard Lee, Reverent C.T. Vivian; black student leaders from SNCC including John Lewis (C.T. Vivian and John Lewis, both lifelong heroic leaders, died on the same day in July 2020), Robert Zellner, who was to become SNCC’s first white field secretary, and the Reverend Andrew Young of the National Council of Churches, soon to administer SCLC’s Citizenship Schools program.

One month later, Lewis, Lee, Vivian and seven other black and white students from the workshop were among those who began freedom rides to desegregate bus waiting room stations in the South.

Before being disbanded, Highlander also held two Youth Project sessions: six weeks of interracial living, focusing on public school desegregation. In 1960, a $10,000 dollar pledge made by Harry Belafonte (which he didn’t completely fulfill) along with individual and foundation grants enabled over forty black, white, Native-American and Mexican-American high school students from nine southern and four northern states to participate in the project: sharing interests in the arts, they took field trips, held panel discussions, attended workshops, worked and played together.

The project’s most sensational result was the arrest and conviction of three children of the Rev. Fred Shuttlesworth for refusing to sit in the back of a Greyhound bus en route home to Birmingham. Their appeal, and their $9 million damage suit against Southeastern Greyhound Lines for its segregationist practices sparked a Justice Dept. probe of the incident.

In conclusion, John Glen writes: “By 1961, the drive for black equality, and Highlander’s role in it, had made some headway. But the gains had been limited, and much remained to be done.”

*********

JOP Editors’ Note: The Highlander Research and Education Center carries on the work of the original school. As they state:

Since 1932, Highlander has centered the experiences of directly-impacted people in our region, knowing that together, we have the solutions to address the challenges we face in our communities and to build more just, equitable, and sustainable systems and structures. Our workshops and programming bring people together across issues, identity, and geography to share and build skills, knowledge, and strategies for transformative social change. This work has created strong movement infrastructure in the South and Appalachia, building networks and organizing efforts that advanced the labor movements of the 1930s and 40s, the Civil Rights Movement of the 1950s and 60s, and environmental, economic, and racial justice organizing across decades.

Today, this work is fortifying movement in the 21st Century by building the leadership of youth, LGBTQ+, and Black and Brown organizers; advancing solidarity economies to dismantle capitalism and extractive industries in our region; creating capacity for movement organizations through fiscal sponsorships and hands-on network support to groups like the Movement for Black Lives and the Southern Movement Assembly; shifting resources to build power within our region; and making sure Southern freedom fighters not only have a seat at decision-making tables, but are leading national and global efforts to shift systems and structures that all too often have incubated oppression and exploitation in our home communities.