By Mel Freilicher

American Jezebel: The Uncommon Life of Anne Hutchinson, the Woman Who Defied the Puritans by Eve LaPlante on Harper/San Francisco, 2004

1

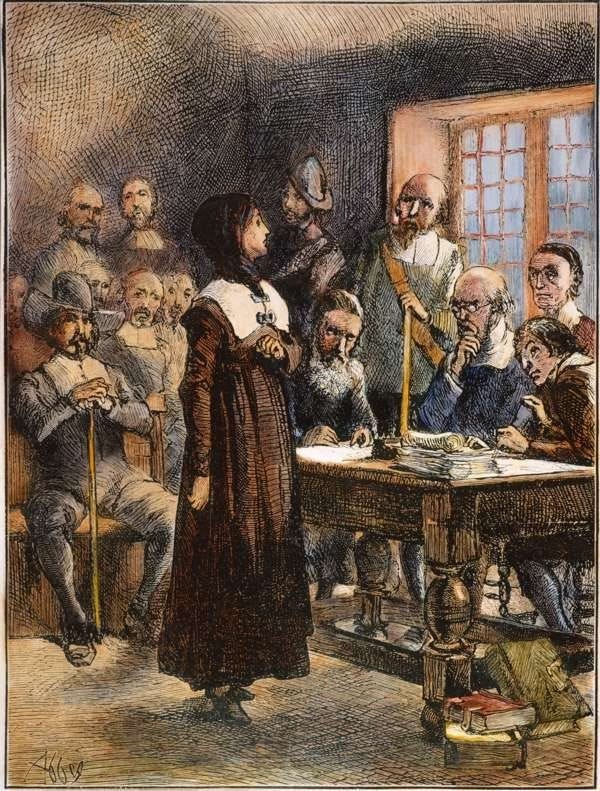

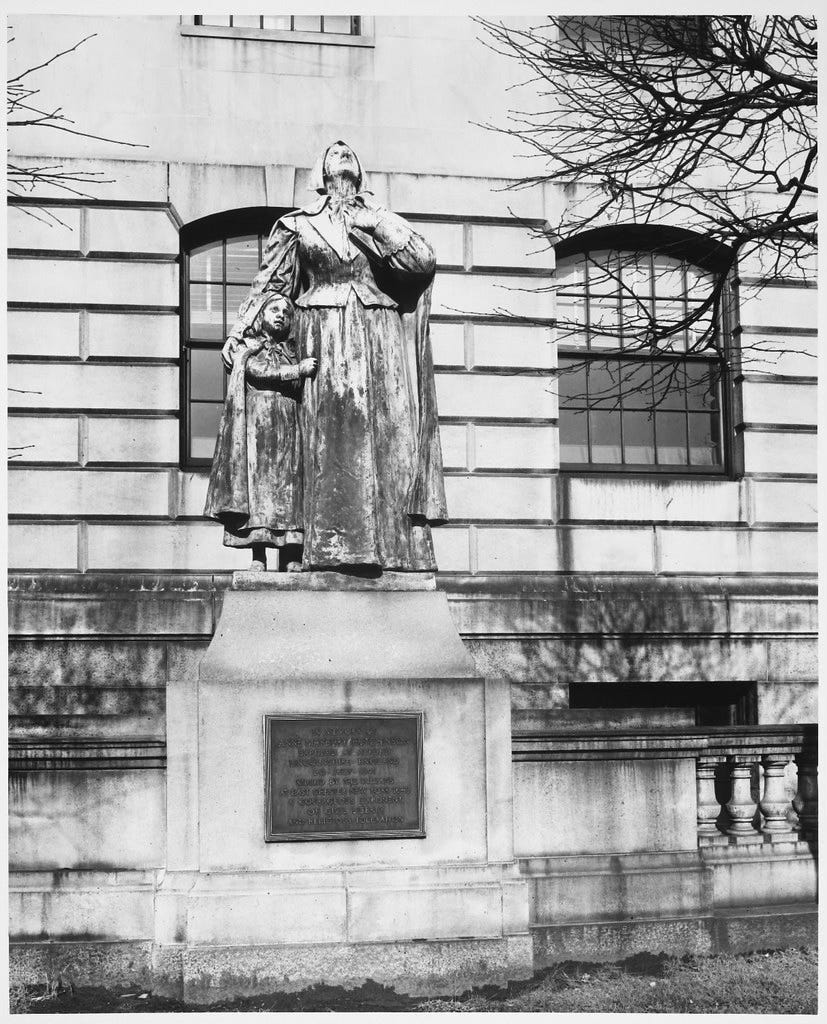

American Jezebel is a lively and scholarly biographical account of Anne Hutchinson, a midwife and mother of 15, who at age 46 was convicted of sedition and heresy in 1637 by forty male judges of the Massachusetts General Court. Excommunicated by the Puritan church, put under house arrest, then banished from the Massachusetts Bay Colony, Hutchinson with some of her disenfranchised followers settled Rhode Island (which later merged with Roger Williams’ Providence Plantation).

Author Eve LaPlante, a direct descendant of Hutchinson, who has degrees from Harvard and Princeton, wrote this book to assist in claiming Hutchinson’s “rightful place as America’s founding mother.” Chapters alternately provide historical profiles of all principal players, and document Hutchinson’s two trials—sometimes providing rather a surfeit of details from court transcripts.

Much of this story’s fascination lies in the complex interplay of early colonial power politics and subtle doctrinal interpretations (whose tremendous impact on colonists’ everyday lives LaPlante makes evident) which Anne espoused at public meetings held at her house to discuss Scripture and theology. Vilified by orthodox Puritan theocrats as too “fluent [in] tongue” and for having a masculine “forwardness in expression,” she held the “strongest constituency of any leader” in the colony.

In a society where women had no civil or ecclesiastical power, Hutchinson was an extraordinary public figure. Barred from the ministry, of course, women could also not vote on church membership, participate in services, or talk in church. Within the meeting house, they were segregated from men, entering by a different door and sitting on a separate side of the building. This custom had no precedent in England and was the colonists’ innovation.

As a trusted midwife and nurse, with extremely high social status, Anne moved freely among the chiefly illiterate women of the Colony. LaPlante rhapsodizes, “As naturally as the women of Boston sought protection from the cold of winter, they came to Anne to quiet their anxieties about salvation…and God’s great and mysterious gift of grace.”

Anne’s “happy and fruitful marriage as well as her evident success as the mother of a large family” also contributed to her social standing. Many of the colony’s women died in childbirth, and nearly half of their children were dead before the age of 5. Even in England, the chance of survival to age 40 was only one in ten.

Her first meetings began informally in 1635, with five or six other women present. To Anne, they seemed like a “natural outgrowth of the spiritual teaching she slipped into her visits to women’s bedsides.” At an appointed hour, week after week, more women came to hear Anne talk about Scripture and salvation in the large parlor of her comfortable house overlooking the sea. In time, some of them brought their husbands, and other freemen came. The demand was so great, within a year Anne was running two evening meetings, often numbering eighty men and women, about one in five adults in Boston.

But Anne never solicited anyone to listen to her, she reminded the court. Her first meetings followed local custom. When she arrived in the colony, women met regularly in their homes to discuss the weekly Bible readings and the ministers’ sermons—“occupying their minds with theology while keeping their hands busy with quilting and embroidery.” These religious discussions, sometimes called “gossipings,” grew out of the ban on women participating in any church activities.

While not encouraged by church authorities, these “conventicles” were allowed by Puritans in England. LaPlante notes it was hard to distinguish such gatherings from those regularly held by Puritan families and small communities for praying, repeating sermons, and singing psalms. While women were officially banned from running conventicles, LaPlante comments, “The division between mother and preacher blurred in a culture that encouraged daily readings and discussion of Scripture…In this way, women in England assumed leading public roles at the local level.”

Among Anne’s supporters were many women and several clergymen, including her brother-in-law, who was banished prior to the trial, and her mentor, Sir John Cotton, a conservative but unorthodox thinker; Hutchinson had revered him in England, but he ultimately disavowed her during the trial. (Cotton was said to be Hawthorne’s model for Arthur Dimmesdale in The Scarlet Letter.)

Staunchest allies were merchants and businessmen, thoroughly resentful of the wage and price controls established by the courts and ministers, as well as the alien exclusion acts which Anne’s nemesis, Governor John Winthrop, had imposed to prevent a larger Hutchinson following. Governor John Winthrop, who was both chief prosecutor and judge at her trial, tagged Anne an “instrument of Satan,” and “this American Jezebel” (emphasis, his).

Winthrop’s camp included most of the colony’s founders and clergy, who were committed to maintaining apparent homogeneity in this “city on the hill”: partly to forestall England demanding the royal charter back and appointing its own colonial governor. Significantly, Anne was allied with the aristocrat, Henry Vane, who had thrice defeated Winthrop in elections for one-year terms as governor. The year before her trial, Winthrop had been reelected (partly due to gerrymandering), which resulted in the Pequot War against native tribes.

The colonial soldiers’ massacre of almost every man, woman and child was termed by one Cambridge pastor, present at Anne’s trial, as “a divine slaughter.” She opposed the war, and most of Anne’s male followers refused to enlist. An attitude echoing that of the already banished Reverend Roger Williams’ “dangerous” refusal to support the conversion (and, if necessary, killing) of Indians in the name of Christ.

Williams, who had been sheltered for months of his exile by the Wampanoag Indians, completely rejected the idea the English king could presume to grant Indian territories to the settlers. He also considered the notion blasphemous of God entering into human transactions by making covenants with pious settlers. Williams argued civic leaders should not govern religious worship, and church members, not public taxes, should pay church expenses.

From today’s vantage point, trial transcripts seem to reveal more ideological similarities than differences between Anne Hutchinson and Winthrop. Both Calvinists, they rejected the Catholic “covenant of works,” as a means of receiving grace, and believed in predestined divine election. Each one wished to purify the church, unlike the Separatists who settled Salem.

However, Anne placed great emphasis on immediate revelation, an individual’s direct communion with God, while Winthrop insisted on established clergymen’s authority to determine who was a saint. Discrediting reliance on outward signs, any striving after assurance of grace was, to Anne, a sure indication grace was not present: an attitude that would “quench all endeavor,” countered Winthrop. (Later, in Rhode Island, a number of Hutchinson’s followers became Quakers, which one scholar saw as the logical culmination of her belief in the “Inward Light.”)

At the trials, Hutchinson is presented as cannily defending, and sometimes modifying, her positions. (“My judgment is not altered though my expression alters.”) But it was clear her beliefs in revelation and even prophecy would never be tolerated, as they undermined clerical authority and potentially elevated women’s power--though Anne herself never questioned the gender hierarchies of the seventeenth century. (Witch hunting, LaPlante points out did not originate in Salem—at least 100 settlers were convicted of witchcraft before that era.)

2

While this study stops short of sketching a psychological profile of Anne Hutchinson, salient features do emerge. Like other significant intellectual women such as Margaret Fuller, Hutchinson was educated at home by a brilliant, unconventional father. Francis Marbury, himself a Puritan reformer, was under church-imposed house arrest when Anne was young. His repeated challenges to the Anglican Church had previously led to censure, imprisonment for several years, and his own trial for heresy. Later, in addition to his ministry, the Reverend Marbury became schoolmaster at one of England’s earliest free schools, established by Queen Elizabeth for the poor.

Anne’s husband, Will Hutchinson, the son of a wealthy textile merchant, was her neighbor in Alford, Lincolnshire, a village of several hundred souls. Described as easygoing and amiable, “apparently drawn to Anne’s fire and light, her mix of virtue and passion,” Will was condemned by Winthrop as “a man of very mild temper and weak parts, and wholly guided by his wife.” LaPlante maintains “his marriage to Anne was one of the great pairings in history,” producing an extremely devoted extended family.

Social status was critical in this culture where even seating in church was determined by wealth: those with more money sat up front. Will had brought to New England a purse containing a thousand gold guineas (equal to many millions of dollars today). Enabling him to purchase an acre in the best part of Boston—right across the road from the governor’s carefully chosen plot—and to build a handsome timber house with a stone foundation and several gables on the second floor.

Anne never shrank from hardships, though. Till their houses were completed in Rhode Island, along with 60 or 70 other settlers, she lived in pits dug in the ground with floors of planks and dirt walls covered in tree bark. Will Hutchinson died at age 55, around the time it was rumored Massachusetts would take over the Rhode Island colony. With her six dependent children, Anne moved again, to the Dutch settlement of Pelham, in what is now the northern Bronx: she’s said to have lived among, but not with, the Dutch.

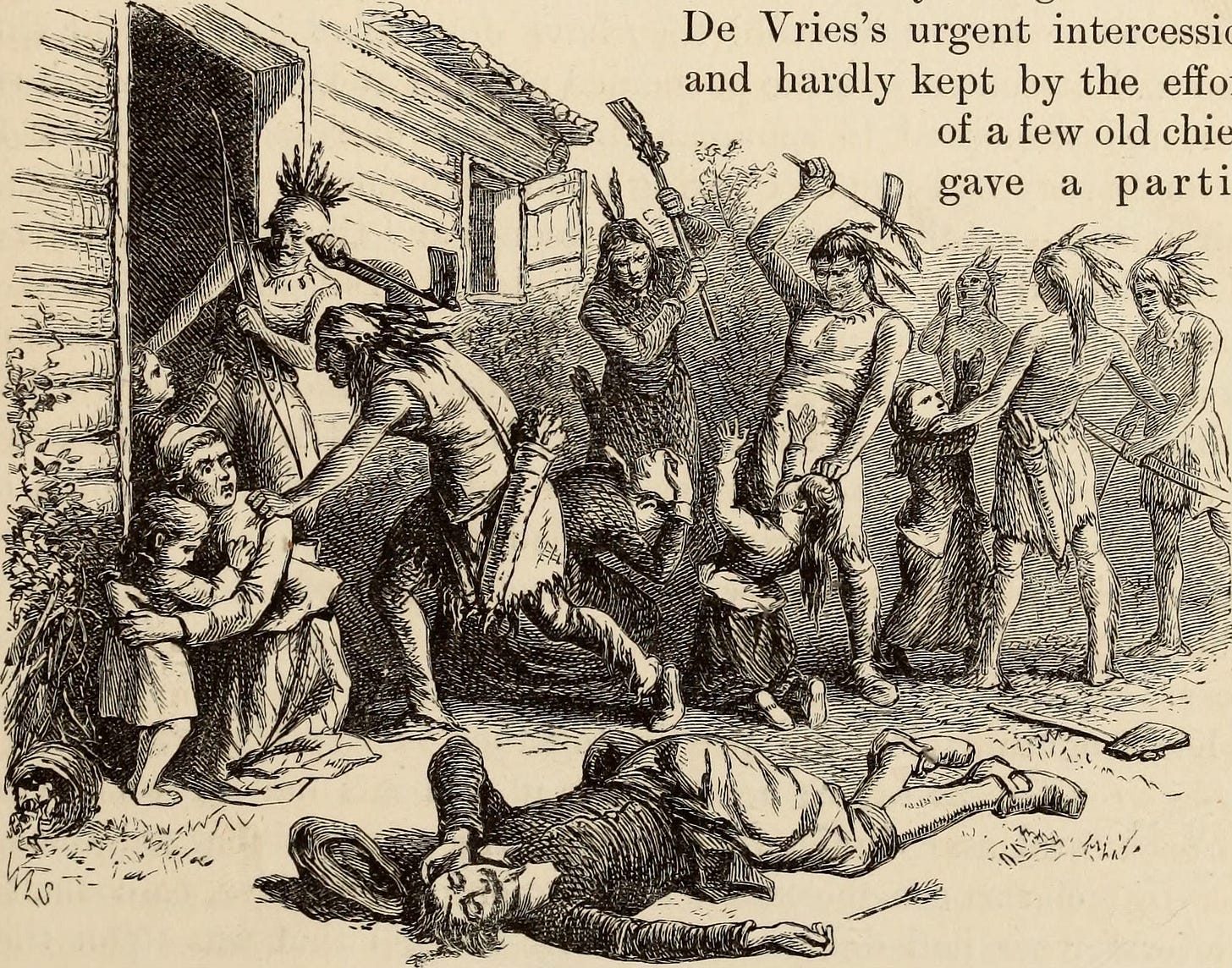

Tragically, all but one daughter soon met their deaths at the hands of Siwanoy warriors, avenging a surprise attack by the Dutch which had killed 80 of their tribe camping out on Manhattan island. Although Anne was warned to either flee or arm herself, she did neither, having always enjoyed friendly relations with other Native Americans.

John Winthrop rejoiced at her death. Continuing to spread vicious rumors about her promiscuity, including sensationalist gossip that Anne had given birth to, then killed, a monster fathered by his former political rival, Henry Vare. (Pregnant during her trial, Anne’s sixteenth child was miscarried.)

3

Anne Hutchinson’s legacy is firmly planted in numerous ways, LaPlante asserts, not the least of which is her being an “[i]nadvertent midwife to a college founded in part to protect posterity from her errors,” as Reverend Peter Gomes, Harvard Professor of Christian Morals, put it in 2002. Harvard was established just one week after Anne’s banishment, in order to indoctrinate young male citizens against charismatic radicals like her. The college’s first board of overseers or trustees comprised six politicians (naturally, including the ubiquitous Winthrop), and six clergymen.

In his 1995 study, The Founding of Harvard College, Samuel Eliot Morison described the school’s obligatory form of worship. “Neither the weekday lectures nor the Lord’s Day assemblies…were services of worship, as worship is understood by Catholics.” Instead, they were “literally meetings of the faithful to offer up prayers in matters of common concern, and to hear Sacred Scripture read, interpreted and expounded by an expert.”

However this may or may not have differed from other religious services, Morison goes on to make the essential point: this expert must not merely be trained in pedagogical methodology, but “he must be ‘learned’ not only in the Sacred Tongues, but in the vast literature of exegesis and interpretation that had grown up around the Scripture.” The grand finale: “There was nothing more dangerous and detestable, in the eyes of orthodox Puritans, than an unlearned teacher pretending to interpret Scripture out of his own head.”

LaPlante comments: “How much more “dangerous and detestable” then, if that “unlearned preacher” was a woman.

This author also asserts the guarantee of religious freedom in the Rhode Island and Providence Plantations “leads directly” to both the rhetoric and substance of the First Amendment to the U.S. Constitution. Beyond this, Anne’s descendants, and their spouses, have played major roles in American history. LaPlante’s brief look at them reflects a dazzlingly vertiginous schizophrenia entirely appropriate to a “founding mother” of this country.

Embodying a wide cross-section of ideologies and allegiances, these individuals include: a president of Harvard College; a captain of the Colonial army who defeated the allied Narragansett, Nipmuck, and Wampanoag tribes; a clan of successful merchants; Quakers; Thomas Hutchinson, chief justice of Massachusetts, then infamous loyalist governor of Massachusetts colony who instigated the Boston Tea Party by attempting to enforce English law; a son-in-law and grandson who were governors of Rhode Island.

In the twentieth century, her sixth great-grandson, Franklin Delano Roosevelt, was president of the United States. FDR’s wife, Eleanor, put Anne Hutchinson at the top of her list of great American women, according to Roosevelt’s biographer. Bizarrely, President George H.W. Bush was a ninth great-grandson of Anne’s. And, of course, at the most nefarious end of the spectrum, Bush progeny, George W, was her tenth great-grandson.

In her eagerness to claim Anne Hutchinson as “America’s founding mother,” the author of this study expresses no political opinions about any of these individuals. She does point out that “an absence remains. In nearly four centuries, not one founder or president has been a woman.” Adding, somewhat tangentially, ”No wonder that as a little girl I associated my ancestor Anne Hutchinson with shame.”

Early on, LaPlante’s introduction states, “Hutchinson haunted Nathanael Hawthorne, who used her as a model for Hester Prynne, the adulterous heroine of The Scarlet Letter.” As that novel opens, LaPlante reminds us, Hester is released from prison, standing beside a rose bush which many believed “had sprung up under the footsteps of the sainted Ann [sic] Hutchison, as she entered the prison door.”

And in conclusion? Anne Hutchinson sounds splendid! American aristocracy is far stranger than fiction, and much less palatable. More or less invisible to the rest of us, except when a particular mandarin chooses to accrue political power.

Bizarre, indeed.