The Labor History Corner

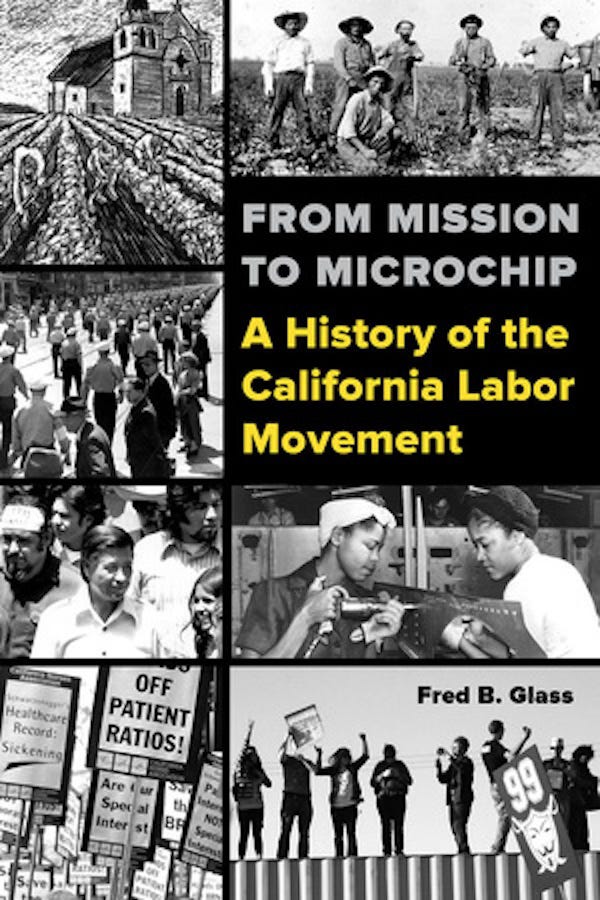

An excerpt from From Mission to Microchip: A History of the California Labor Movement By Fred Glass

A version of this article appeared on the California Labor Federation California Labor History website. You can buy From Mission to Microchip: A History of the California Labor Movement from the University of California Press.

Changing history depends on knowing history

What does it take to change the course of history? Awareness of the potential to change it, at the very least.

At the peak of unionization in the 1950s, more than 40% of California’s non-farm workforce belonged to unions. The volunteer activism of union members in the mid twentieth century lifted the working class majority up into the “middle class” of homeownership and disposable income. Today, with union density at its lowest point in nearly a century, two and a half million Californians still carry union cards, but only representing 16%.

California labor history doesn’t begin and end with union membership. Unions are but one part of a broader saga, repeated countless times—in coastal seaports, Central Valley farms, southern oilfields and Sierra foothills, in corporate high rises and bungalow classrooms—of workers’ journeys from isolation and powerlessness to community, strength and hope. The toolbox of that story contains unions, to be sure; but also legislation, election campaigns, legal battles, community murals, songs, demonstrations, and a mountain of dedication by ordinary people to shared ideas of fairness and social justice.

Some union activists became famous, like farm worker Cesar Chavez and longshoreman Harry Bridges. Most remain unknown, like Anna Smith, the widow of a disabled Civil War veteran, and single mother, who migrated to the state in 1875. She spoke at demonstrations called by the Workingmen’s Party of California in the late 1870s, and led several hundred workers—who had elected her their “general”—on a march intending to join ‘Coxey’s Army’ in Washington, D.C. protesting against the horrendous economic depression of the early 1890s.

Also all but unknown today are events like the 1934 San Francisco General Strike, where a struggle by dock workers and sailors against terrible wages and unfair and oppressive hiring practices escalated due to violent employer resistance.

Following police killings of strikers, and a massive response by unions that shut down the city for several days, the maritime workers achieved union recognition, a fair contract, and a hiring hall that shared the available work equally.

Beyond these advances, the General Strike contributed to sentiments in the United States Congress that led to passage of the National Labor Relations Act a year later. In its wake, millions joined unions in California and across the country. For many people, especially immigrants, the unions they joined in the 1930s provided their first access to participation in democratic institutions, economic security, and home ownership.

After World War II, California changed in important ways. So did the ways workers approached solving their problems. In place of direct workplace action, workers more often concentrated on political and legislative activities. The 1958 statewide election campaign pitted a coalition of labor federations and civil rights groups against the gubernatorial ambition of a wealthy newspaper owner from Oakland, U.S. Senator William Knowland, who bankrolled an anti-union “Right to Work” initiative on the same ballot.

Fred Glass is the author of From Mission to Microchip: A History of the California Labor Movement (UC Press, 2016) and a member of the State Committee of California DSA

Stay tuned for next week’s installment…