By Mel Freilicher

Ben Fletcher: The Life and Times of a Black Wobbly by Peter Cole on PM Press, 2021

“Benjamin Harrison Fletcher surely ranks among the greatest African Americans of his generation and top echelon of black unionists and radicals in all of US history”—the opening sentence of Peter Cole’s introduction.

Fletcher “helped lead a pathbreaking union that likely was the most diverse and integrated organization (not simply union) despite the era’s rampant racism, anti-unionism and xenophobia.” Cole’s volume is intended to recognize this forgotten (“save for aficionados of black labor and radical history”) IWW organizer who in 1913, at age 23, became the leader of Philadelphia’s longshoremen, the last major port workforce to be unionized.

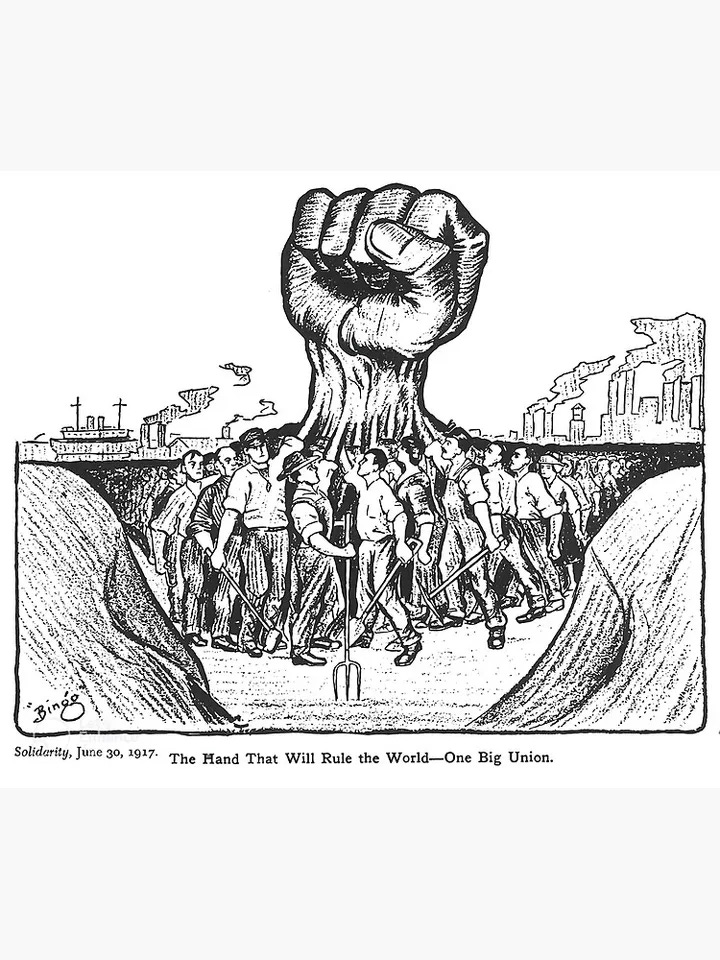

Famously, of course, the IWW advocated one big union, representing not just specific crafts, like the virtually all white AFL—and very much unlike them, dedicated to the overthrow of capitalism. The newly created Local 8 was initially composed of roughly one-third African Americans, one-third Irish and Irish-Americans, and one-third immigrants from other European countries. All work crews were thoroughly integrated and remained so during the 10 years the IWW dominated the Philadelphia waterfront.

A young Ben Fletcher started working along the Philadelphia shore, joining the IWW in 1910 or ’11, and rapidly developing into an accomplished speaker or “soapboxer.” In 1913, approximately 4,000 Philadelphia longshoremen walked off their jobs: a little over half were African American, the remaining mostly Polish, Lithuanian, and Irish immigrants. Both AFL and IWW organizers quickly materialized, hoping to convince strikers to join their respective unions.

Pitched battles were fought among strikers, sympathizers—including hundreds of women, most likely family members, and Wobbly longshoremen from other Atlantic ports--against police who protected strikebreakers. An IWW leader was beaten unconscious by the police and thrown in jail without charges. Despite the government-employer coalition, between twenty and thirty ships were tied up at any one time. Fletcher and Wobbly leaders attempted to take the strike to other Atlantic ports, asking longshoremen in Baltimore and New York not to unload “hot cargo” from Philadelphia ships.

After two weeks, in which dozens of ships remained anchored and idle, bosses gave in, and Local 8 secured its place on the waterfront. The agreement with management initiated, for the first time, overtime and double time pay for Sundays and holidays. Particularly significant, Cole points out, in an industry where longshoremen typically worked shifts of 24 to 36 hours. The bosses agreed not to discriminate against striking workers. This initial settlement was oral, lasting for a year: the union refused to sign a contract so workers could retain their greatest weapon—the strike.

Philadelphia longshoremen chose to join the IWW, rather than the mainstream ILA, an AFL union, partly due to the success of the mammoth, Wobbly-led silk workers strike earlier that year in nearby Paterson, New Jersey. Nationally, IWW already included maritime workers along the Atlantic and Pacific, as well as the Gulf and Great Lakes coasts. “The most reasonable explanation is also the most basic,” Peter Cole argues. “There were simply too many black workers to ignore and the IWW’s ideology of inclusivity resonated far stronger with this group than the AFL’s.”

Local 8 proved powerful enough to stop the oppressive hiring practice known as the shape-up, which existed in every other port in the U.S. and many worldwide. Hundreds would show up for work for the bosses to pick: forcing workers into competition, resulting in lower wages, longer hours and more dangerous workplaces. Local 8 instituted a system in which employers called the union hall, requesting workers for dispatch. Only dues paying unionists with buttons were eligible; periodically management tested this by hiring outside of Local 8—provoking countless conflicts, usually short-lived and rarely documented.

Wobblies attempted to organize every worker with a role in the maritime transport industry: in the coastal and banana trades, railroad pier workers, dockside sugar refinery workers and teamsters. Proving so successful the AFL secretary of ILA for the Atlantic district wrote his superiors, “The city [i.e. the port] was in absolute control of the IWW.” Within a few months of Local 8’s creation, workers on barges and small boats up and down the Delaware River organized a branch within the union and struck for higher wages.

To celebrate their first anniversary, Local 8 members decided to throw themselves a party. Employers threatened to fire anyone who didn’t show up that Saturday (a six-day work week was the norm before the Fair Labor Standards Act of 1938). With three bands in tow, on the appointed day, close to 2,500 longshoremen, virtually the entire deep-sea workforce, took the day off. Wobblies marched through South Philadelphia then downtown.

After the parade came the picnic’s round of obligatory speeches in English and Polish. Fletcher, recently elected secretary of Philly’s IWW District Council, encouraged his [black] friends to write ‘down home’ in order to increase the union’s visibility in the South. Then music, dancing, baseball and other sports.

A war-induced recession in the maritime economy hurt ports and union activity. When it sparked again in 1915, Fletcher was among the leaders who helped convince workers in several of the notorious anti-union piers to join a strike. He also traveled regularly to organize port cities, especially where the AFL excluded or segregated black dockworkers. Personally known as far south as Norfolk, Virginia and as far north as Boston, Fletcher’s most concerted efforts focused on his home port’s rival, Baltimore, where the generally transient nature of workers, including those who signed up with the IWW, contrasted sharply with local 8 which remained a large, interracial and durable outpost.

Strikingly, Ben Fletcher was the only black man arrested for violating the 1917 Espionage Act, along with “Big Bill” Haywood and l65 leading IWW organizers. Other charges: interfering with the selective Service Act, conspiring to strike; violating the constitutional rights of employers executing government contracts; and using the mail to defraud employers.

No specific testimony was ever presented against Fletcher. The great majority of evidence at these trials came from Wobbly publications written prior to WWI—generally viewed by the left, and rightly so, as a voracious and craven imperialist, free-for-all land grab. Once the war began, the union took no official position. IWW members’ sentiments were divided: some joined the military.

Ironically, earlier that year, in a mass meeting, the IWW branch of Philly longshoremen voted not to strike for the duration of the war, a position contrary to The Messenger’s. Not only did that socialist-leaning paper oppose the war, but its editors urged African Americans to resist being drafted, and to join radical organizations fighting for an integrated society.

Sentenced to l0 years at age 27, Fletcher did 2 1/2 of them. In the courtroom, Bill Haywood reported, Ben Fletcher “sidled over to me and said, ’The Judge has been using very ungrammatical language. His sentences are much too long.’” Fletcher’s joke spread far and wide, “repeated many times in various sources.”

Despite severe restrictions and surveillance, the incarcerated Wobblies started to organize Leavenworth (the first, and then still largest, Federal Penitentiary), receiving permission to publish a “News and Views from the Labor World” column in the prison newspaper. Legal struggles entailed extended correspondence with the IWW General Defense Committee, and other activists. Chiefly, for Fletcher that meant: John Reed, author of the classic about the Russian Revolution, Ten Days that Shook the World; Oswald Villard, a cofounder of the NAACP and grandson of the prominent abolitionist, William Lloyd Garrison; and Joe Ettor, an Italian Wobbly organizer.

After the war ended, President Harding slowly began commuting IWW sentences. Franklin D. Roosevelt granted Fletcher a full pardon in 1933.

The arrested men were thought to be communists, but Fletcher hated the Party’s centralized authoritarian and antidemocratic secret committees. (Lenin had cracked down on anarchists and syndicalists early in the revolution.) It was understood communists very much wanted to “turn” the IWW into the Bolshevik vanguard in the States. Firmly agreeing with the union’s decision to remain committed to a socialist society, Fletcher also remained anticommunist. Eventually, the CP tried to utilize the AFL, rather unsuccessfully, by “boring from within.”

A lifelong member of the Socialist Party of America, Bill Haywood and W.E.B. Dubois joined Fletcher, eventually dropping out, the latter because of the racism of some of its leaders and members. In fact, the Socialist Party had few black members. As Jeffrey B. Perry notes in his meticulously thorough account, Hubert Harrison: The Voice of Harlem Radicalism, 1883-1918, the Party “offered no special program, had a weak record on the ‘Negro’ question, and opposed reforms that were badly needed in the African American community.”

In its heyday (before the Anti-Sedition Act heralded the glorious War to End All Wars), the Socialist Party was considered by many to be a viable part of a growing radical movement posing a threat to capitalism. Entering a period of rapid growth, membership jumped from 58,000 to 125,000 in two years. In 1912 alone some 1,039 Party members were elected to public office, including 56 mayors, 18 state representatives, and 2 state senators. Their press boasted 8 foreign language and 5 English dailies, 36 foreign language and 262 English language weeklies.

Although there was significant support within the Party for the IWW, the dominant political faction, led by Victor Berger, opposed the Wobblies, favoring working inside AFL unions. As early as 1901, the Party had taken a position to not interfere in internal trade union questions, “at a time when many AFL unions had racial exclusion policies.”

Socialist Party members held widely disparate views on racial equality. Several years before becoming their first elected congressman in 1910, Victor Berger had argued that “negroes and mulattoes constitute a lower race.” Perry cites historian Philip Foner’s comments: individual members’ attitudes ran the gamut from outright advocacy of white supremacy through the (rather commonplace) attitude on the left about race being “a class problem and nothing more, to the position that the Socialist Party should conduct a consistent and persistent struggle against racism.”

Incidentally, the most famous Socialist Party leader, Eugene Debs, candidate for president five times, received over 919,000 votes, while in prison for opposing the war. Born in 1856 in Terre Haute, Indiana, Debs became a Democratic member of the state’s General Assembly in 1889, after serving 2 terms as Terre Haute City Clerk. Considered one of the best Party members on the “Negro question”—refusing to speak to segregated audiences in the South—Debs nevertheless argued the class struggle was “colorless”: there was no need for special appeals to reach African Americans who he considered part of the general labor struggle.

He, too, was pardoned by President Harding in 1921, partly due to pressure from the left, particularly from Kate Richards O’Hare, Socialist Party activist who herself had been imprisoned after the 1917 Espionage Act. Ignoring warnings, O’Hare toured the country with her 14-year-old daughter demanding freedom for Debs. In Twin Falls, Idaho, she was abducted by three carloads of vigilantes, led by the local American Legion commander. Driving her more than 150 miles before the car broke down, she was then able, or allowed, to escape outside a small town in Nevada, Adam Hochschild writes in his excellent, American Midnight: The Great War, A Violent Peace, and Democracy’s Forgotten Crisis.

The following year, O’Hare and her husband, Frank, came up with a “living petition” plan to free other political prisoners by heading to Washington with members of their families. Thirty-seven women and children moved into a house rented by supporters, tried to enter a church service the president was attending, and started picketing the White House with signs like NO PROFITEERS WENT TO PRISON. After several months, 50 more prisoners were released.

Out on bail, Ben Fletcher continued his organizing activities, despite the threat of being thrown back in jail. Helping to raise bail for still incarcerated Wobblies, he was also active in by far and away the largest strike in the Philadelphia port: part of a national and international labor uprising in the aftermath of WWI. Traveling to Baltimore to share news of the strike and to discourage the unloading of hot cargo, with the help of some shop firemen belonging to one of the more militant maritime unions, Fletcher convinced 4 vessels to strike in sympathy with Local 8.

He also spoke at one of the major coal miner strikes in Harlan County, Kentucky. Alongside Roger Baldwin, founding director of the American Civil Liberties Union, legendary theologian Rienhold Niebuhr, and Norman Thomas, nicknamed “Mr. Socialism,” the public face of the Socialist Party, six times its candidate for President, in the generation after Debs.

Because Fletcher never graduated high school, and was an activist, not a theoretician, he left no archives or writings about himself. Whatever materials the US government confiscated in its 1917 raid of Local 8 disappeared long ago, probably burned up, along with all other IWW documents seized in raids of their national offices. Aside from his biographical sketch, Cole states “the majority of this book consists of a series of document--some quite short, none more than a few pages—that, together, chronicle Fletcher’s…public life in the IWW.”

Such research was clearly a labor of love. Great thanks due to Peter Cole for bringing Fletcher’s life back into the public sphere; similarly, to PM Press for publishing this volume. The press’s promotional material states they are “an independent, radical publisher of books and media to educate, entertain and inspire. Founded in 2007 by a small group of people with decades of publishing, media and organizing experience, PM Press amplifies the voices of radical authors, artists, and activists.” Their statement ends with, ”We’re old enough to know what we’re doing and young enough to know what’s at stake.”

Documents include some 240 pages of articles and obituaries about Fletcher, especially those published in The Messenger, which dubbed him “the most prominent Negro labor leader in America.” Edited by radical black intellectuals, Chandler Owen (who claimed The Messenger’s readership was two-thirds white) and A. Philip Randolph, both members of the Socialist Party of America.

After a stint as managing editor of The Chicago Bee, a major African American newspaper, in the 1930’s Owen turned toward the right, and was active in the Republican Party. A reluctant consultant on race relations for FDR’s Office of War Information, he later became a speech writer and consultant for Dwight Eisenhower.

A major civil rights activist, A. Philip Randolph organized, and in 1925 become President of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters, the first successful black-controlled labor union. In 1941, he basically forced FDR to issue an executive order barring discrimination in WW11 defense industries, by threatening to lead 50,000 African Americans marching on Washington.

An instigator of the landmark 1963 March on Washington where his close friend, Martin Luther King, Jr, gave his “I Have a Dream” speech, Randolph continued to successfully push the Truman administration on workplace discrimination issues, and inspired the “Freedom Budget,” aimed at dealing with economic problems faced by blacks.

Little is known about Fletcher’s personal life. Born in 1890 in Philadelphia, he lost his mother sometime before age 15. It’s believed Ben’s parents may have started their own lives as slaves, and in the 1880s separately escaped racist horrors of the Jim Crow South. Philadelphia, then the country’s third largest city, was historically progressive, home to the largest black population of any city outside the South.

As early as 1780, soon after U.S. independence, the state of Pennsylvania passed a law to gradually and slowly abolish slavery. A hotbed of abolitionism by the 1830s, due to the relatively liberal politics of the region’s white Quaker community (some of whom were slaveholders), many “free blacks” moved to the city. Nevertheless, early streetcars were segregated, and many white employers refused to hire black men.

On three occasions before the Civil War, large white mobs rampaged through black neighborhoods, beating and killing innocent residents as well as targeting white abolitionists. In 1838, the Pennsylvania Anti-Slavery Society built a sumptuous, 3-storey hall with meeting rooms and a large auditorium which could seat perhaps as many as 3000 people. The building was burned to the ground 4 days after it opened.

A mob broke into the empty building, setting fire to draperies and furniture. Volunteer fire companies doused the adjacent structure but did nothing to stop the burning of the Hall. Only after the mob headed for the center of the African American community, attacking the first African Presbyterian church, and a colored orphanage, did the mayor send in the police. At the trial, the county defended itself, accusing abolitionists of causing the fire by the provocative act of hosting an interracial meeting.

Almost lynched when he’d been agitating in Norfolk, one of the largest ports in the South where African American longshoremen predominated, friends smuggled Fletcher aboard a northbound ship to Boston. There Ben met and married a white woman, New York-born Carrie Danno Bartlett, just a month before his indictment. (Massachusetts had repealed its anti-miscegenation laws in 1843, one of the first states to do so. About half the country still had laws banning interracial marriage in the 1910s.)

Sometime in the 1920s, Fletcher and his wife divorced; what happened to her is unknown. In the ‘30s, he married a much younger black woman named Clara. It’s unclear how they made a living—some said he hand-rolled cigars—but Clara was a nurse and almost certainly the household’s primary breadwinner.

The couple moved to the Bedford-Stuyvesant neighborhood in Brooklyn where they led an active social life with friends and extended family (he had no children). Ben Fletcher suffered his first stroke at 42, in 1933. His health declined rapidly. He died in 1949 at age 59.

An obituary issued by the Associated Negro Press, founded in Chicago in 1919, serving about 150 U.S.-based, and l00 newspapers in Africa in both English and French, discusses some of the strikes Fletcher was involved in, as well, of course, as his imprisonment. It goes on: “One of the most brilliant Negroes ever associated with a leftist organization, Ben Fletcher was highly respected for his scholastic ability and his rhetorical efforts.

He was one of the first Negroes to be associated with the IWW in an organizational capacity and upon release from penitentiary, found employment in the field he loved so well. Fletcher’s life was adventurous and stormy, but in his later years, he lived very quietly and worked with a labor organization near Union Square.

At the time of Fletcher’s arrest and conviction mass hysteria swept the country, and new laws, Criminal syndicalism made its appearance in California as a weapon to prosecute supposed subversives.”

Mel Freilicher retired from some 4 decades of teaching in UCSD's Lit. Dept./ writing program. He was publisher and co-editor of Crawl Out Your Window magazine (1974-89), a journal of the experimental literature and visual arts of the San Diego/Tijuana region. He's been writing for quite some time. He is the author of The Unmaking of Americans: 7 Lives, Encyclopedia of Rebels, and American Cream, all on San Diego City Works Press.