By Mel Freilicher

The Other American: The Life of Michael Harrington by Maurice Isserman on Public Affairs, 2000

Paving the way in the early part of the decade, before all hell broke loose in the mid to late l960s, were several social critics, who managed to garner a lot of attention. Rachel Carson’s 1962 Silent Spring was a wake-up call about the indiscriminate use of pesticides in destroying the environment; many had been developed during WWII and used by our military. The next year came investigative reporter Jessica Mitford’s The American Way of Death, an expose of abuses in America’s funeral industry.

Jessica Mitford came from an infamous British aristocratic family. Two of her six sisters were fascists: Diana married British fascist leader Sir Oswald Mosley (the couple were jailed from 1940 to ’43); Unity was a close friend of Hitler’s and shot herself in the head the day Britain declared war on Germany, leaving her brain damaged the rest of her life. Nancy was a successful novelist. Jessica and her husband, members of the CPUSA, refused to testify in front of HUAC, then left the Party in 1958.

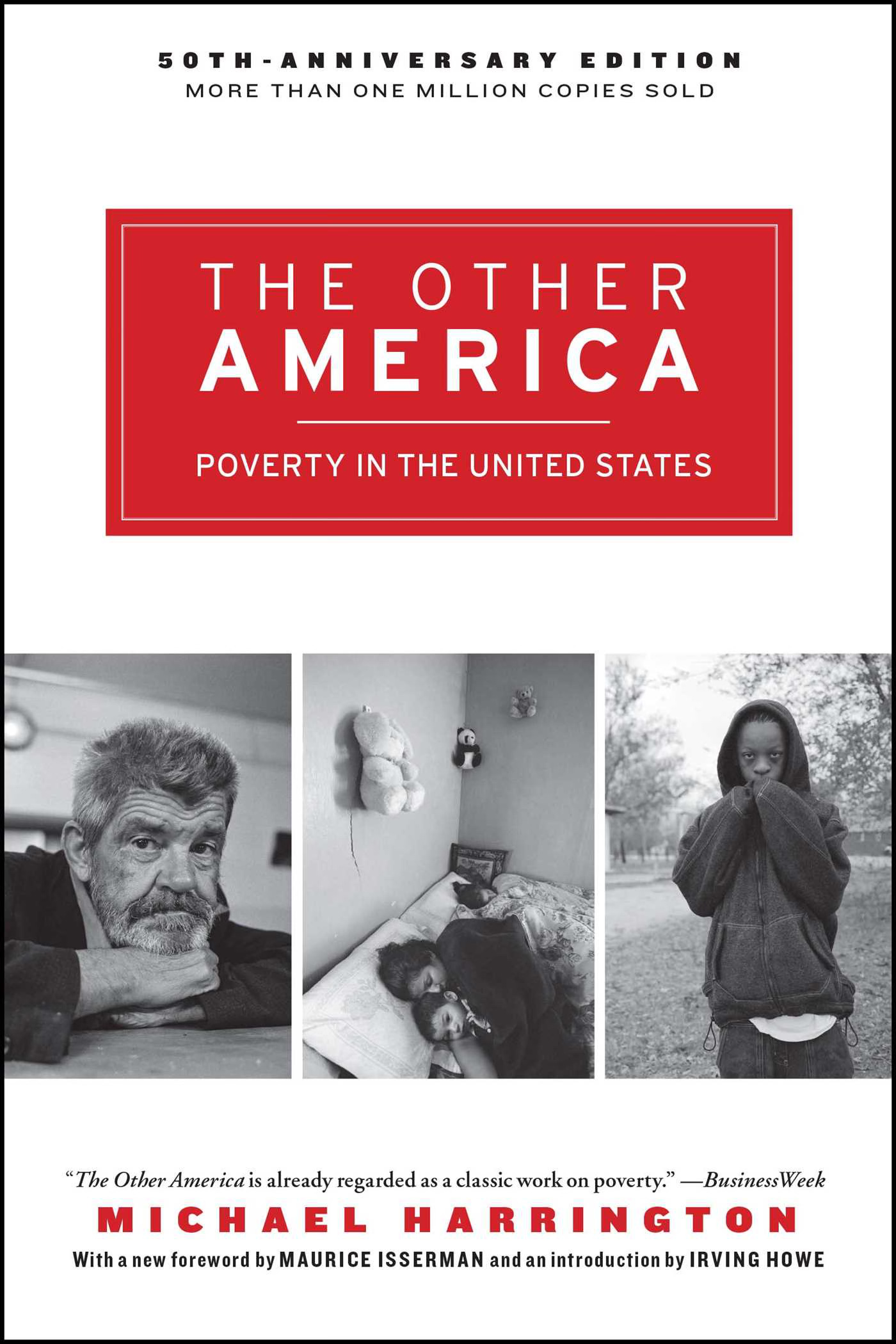

Michael Harrington’s The Other America challenged the then almost universally accepted idea that this country had helped all but a tiny minority of its citizens to a fair share of its astonishing post-war abundance. Harrington’s chief contribution came in his developing argument about “the culture of poverty,” the guiding concept of a recently published ethnography by the radically inclined anthropologist, Oscar Lewis, in Five Families: Mexican Case Studies in the Culture of Poverty.

Echoing Lewis’ idea that poverty is not simply “the way of life of the poor,” but functions as a distinct subculture of family structure, interpersonal relations, time orientations, value systems, and spending patterns, Harrington’s 1962 study called for a broad and systemic program of “remedial action…a comprehensive assault on the part of the federal government, entailing housing, schools, medical care, labor standards, communal institutions.”

Harrington argued the poor were “victims of the very inventions and machines that have provided a higher standard of living for the rest of the society.” Mechanization of industry and agriculture had eliminated many of the unskilled and entry level jobs which had formerly sustained them.

His timing was remarkably fortuitous. John Kennedy had spent several well-publicized weeks campaigning in West Virginia for the presidential nomination. Several months later, CBS News broadcast a special hour-long documentary, narrated by Edward R. Murrow, entitled Harvest of Shame, tracing the plight of migrant farm workers.

The Other America sold moderately well and was received enthusiastically by the liberal press. But only after returning from a year abroad did Harrington realize what a celebrity he’d become. In his first State of the Union address, President Lyndon Johnson announced a major new government initiative to combat poverty, and ABC radio asked Harrington to serve as commentator.

Featured in Time and Newsweek, Harrington was besieged with invitations to write articles and speak at universities. In the next few years, his book went through several more printings, causing Business Week to note it was already regarded as a “classic work on poverty.”

Although included in Johnson’s anti-poverty task force, Harrington found himself marginalized from the start, and soon became skeptical about the government stepping in to organize the poor. His stint as an insider was as short-lived as the War on Poverty itself, which was quickly overshadowed by Johnson’s obsession with Vietnam (or, rather with not being the president who lost that insane war). Once the public face of poverty changed from the iconic white Appalachian to black urban dwellers, Harrington was also increasingly subjected to backlash.

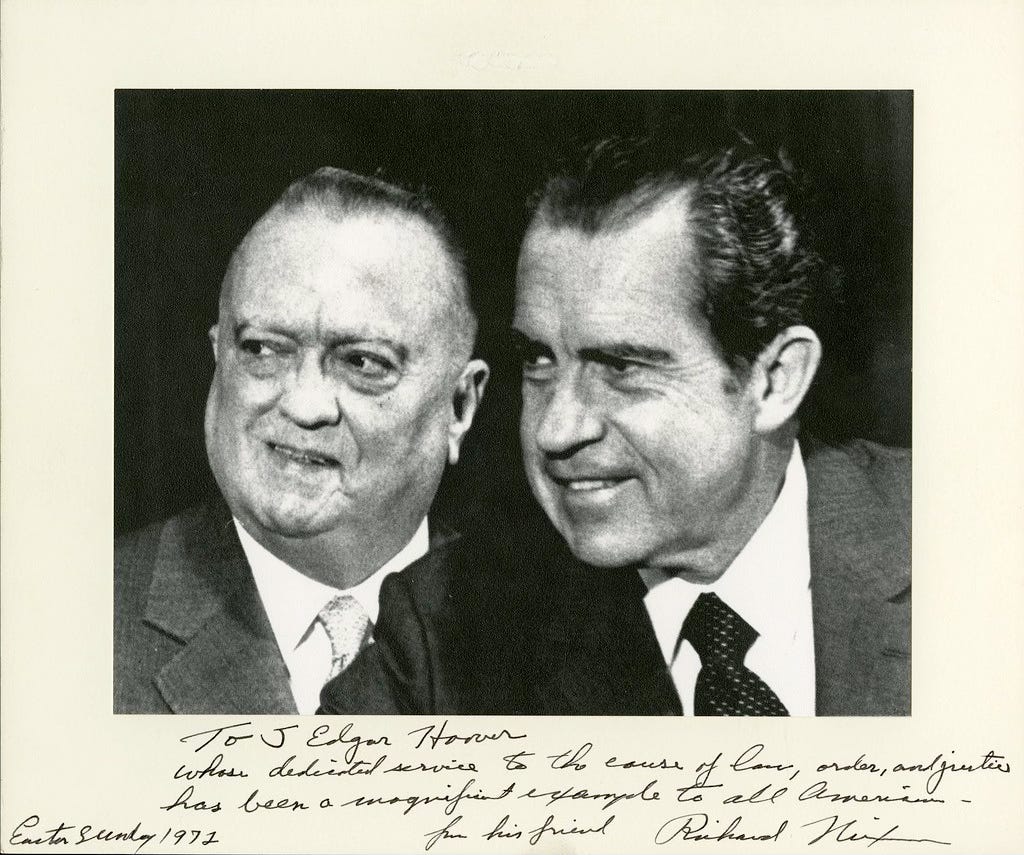

He was placed on the FBI Index in 1956. Using his experience as a clerk in the Library of Congress to create an index system utilizing extensive cross-referencing, initially J. Edgar Hoover’s cards covered 150,000 people. By 1939, his master list contained more than l0 million names.

From the ‘50s through to the ‘70s, heinous Hoover added an untold number of U.S. activists he considered “dangerous characters”: to be incarcerated in detention camps in case of a national emergency. Later, Harrington was added to the master list of Nixon’s political opponents.

Maurice Isserman’s thorough biography puts Michael Harrington’s life into context of his long history of social concerns and involvement in American socialist politics. Born into an affluent professional family in St. Louis, Harrington attended excellent Jesuit schools and colleges, then moved to Greenwich Village, attracted by its bohemian lifestyle (regulars at Café San Remo included James Agee, Merce Cunningham, John Cage, Judith Malina, and Paul Goodman).

Beginning to write for the Catholic Worker—which had more than twice the combined circulation of the Nation and the New Republic, the country’s preeminent liberal weeklies—he was an editor of the paper from 1951 to ’53. Harrington was greatly influenced by founder Dorothy Day, who was widely read in socialist and anarchist literature and close to the leading radicals, Greenwich Village intellectuals and artists of her era.

After a bohemian youth, Day had converted to Catholicism. In the 1930’s, she worked closely with Peter Maurin to found the Catholic Workers, and its newspaper, an unapologetic example of advocacy journalism, which Day edited until her death in 1980 at age 83. Its chief competition was the CP’s The Daily Worker. The first issue of Day’s paper posed the question: Is it not possible to be radical and not an atheist?

The Catholic Workers was a strong pacifist movement combining direct aid (food and shelter) for the poor and homeless with nonviolent, direct action on their behalf. Needless to say, Dorothy Day was arrested numerous times, the last being in 1973 at age 75.

Becoming disaffected with religion, Harrington jumped into involvement with Socialist politics in the early 1950’s amid its diminishing effectiveness and tedious factional squabbles which, oddly, he apparently relished. Harrington emerges as a uniquely thoughtful and committed individual who attempted quite unsuccessfully to bridge various gaps within the Left—from Norman Thomas to Tom Hayden.

While labor historian Isserman’s examination of the exhausting political in-fighting is incredibly detailed, unfortunately Harrington’s personal life gets short shrift. A discussion of his psychoanalysis, breakdown and eventual recovery might have added some valuable insight. As is, it’s difficult to understand some of Harrington’s more obstinate and counter-productive positions.

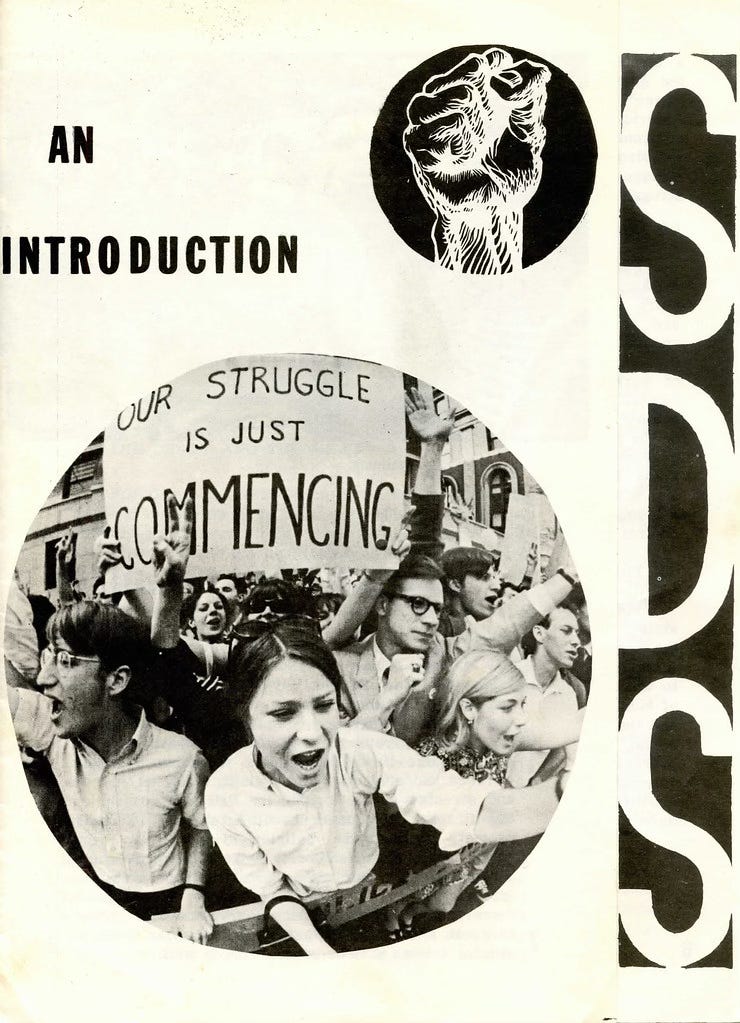

For example, as a leader of the parent socialist organization which sponsored the 1962 Port Huron conference of the newly formed Students for a Democratic Society (SDS), Harrington tried to insist Communist Party members be banned from the nascent organization.

The socialists forbade SDS to send out communications, even locking them out of the office. SDS members simply changed the locks and confiscated the mailing lists. Just a year earlier, Tom Hayden had listed Harrington as one of the three radical leaders over the age of 30 who had “won the respect” of New Leftists, along with C. Wright Mills, and Norman Thomas. (Arthur Schlesinger, Sr. called Harrington the “only respectable radical in America.”)

But the social Democratic left—notably Harrington, Irving Howe, and Bayard Rustin—would play no viable role in the anti-Vietnam war movement. Over the next few years, they compounded their errors by calling for a negotiated settlement with Vietnam instead of the unilateral withdrawal demanded by the New Left, while also harping on the idea that the “only effective peace movement” would be one which disassociated itself from the Viet Cong.

For a while, Harrington maintained the position that the U.S. could pursue both “guns and butter”—the war needn’t be fought at the expense of domestic poverty programs—a stance for which he later apologized repeatedly.

Harrington’s anti-Communist dogma seems inexplicable since ranks of the Communist Party USA had been decimated in the 1950’s, due to McCarthyism, HUAC, and Nikita Khrushchev’s startling “Secret Speech,” to Party members here denouncing Stalin’s brutal purges and mock trials over the decades and ushering in a less repressive era in the Soviet Union. (In the ‘50s, before his death, Stalin was getting ready to purge the Jews, many of whom had been active in the revolution.)

Further, most SDS’ers shared the attitude that “’participatory democracy’ was at least as much at odds with communism as capitalism.”

Remaining active in socialist politics until his death from cancer at the age of 61, in the 1970’s and ‘80s, Harrington was involved with forming spin-off organizations from the Socialist Party. First, as a leading founder of Democratic Socialist Organizing Committee (DSOC) which called for a ceasefire and immediate withdrawal from Vietnam and supported presidential candidate George McGovern.

Ron Dellums, a progressive African American mayor of Oakland then member of the US House of Representatives, was a prominent member of DSOC. Dellums also had the distinction of making Nixon’s Enemies List.

DSOC merged with New American Movement (NAM) in 1983 to form the Democratic Socialists of America (DSA). Harrington and socialist feminist author Barbara Ehrenreich were co-chairs; the Vice-Chair was “Red” Dorothy Healey, a well-known former leader of the CPUSA who left the Party in 1973 (having desperately trying to reorganize it after Khrushchev’s devastating 1956 speech), was one of the founders of NAM, which rejected the strategy of building a “vanguard party” in favor of a decentralized association of local “chapters.”

Isserman remarks “no claimant has emerged to pick up the mantle” of Eugene Debs, Norman Thomas, and Harrington himself. “Michael seems to represent the end of the line” of individuals prepared to dedicate their lives to building a socialist organization.

The biography ends on an elegiac note: “An honorable, even heroic, vision, it was also, as Harington reluctantly conceded in the last years of his life, one for which there remained precious little room in American political culture.”

Since this book was written in 2000, DSA hadn’t yet emerged as the left wing of the Democratic Party. The organization grew considerably when Bernie Sanders was a possible presidential candidate; four members of “the Squad,” including AOC, are DSA members.

Mel Freilicher retired from some 4 decades of teaching in UCSD's Lit. Dept./ writing program. He was publisher and co-editor of Crawl Out Your Window magazine (1974-89), a journal of the experimental literature and visual arts of the San Diego/Tijuana region. He's been writing for quite some time. He is the author of The Unmaking of Americans: 7 Lives, Encyclopedia of Rebels, and American Cream, all on San Diego City Works Press.