By Fred Glass

The 1960s saw the rise of a powerful movement for unionism by workers employed in public service jobs. It was fueled by the example of the civil rights movement, with its courageous moral stand and non-violent civil disobedience tactics. Like farm workers, public sector unionists received tangible support from strong private sector unions. But more than anything else, public sector unionism benefited from the prosperity of a society that, through a mature labor movement and voter support for government services, provided the people of the United States with the most equitable distribution of wealth it achieved before or since.

The expansion of government programs at all levels in the 1960s was the result of a consensus in place from the New Deal on that a strong economy depended on investing in a robust public sector to provide education, safety, health and security for the general population. It was a society that could afford to be organized, and in which living traditions of collective struggle helped make sure that it was.

Social workers lead the way

In August 1963, a dozen social workers in the Los Angeles County Department of Charities formed a “Social Workers Action Committee.” They were members of what was then called Building Service Employees International Union (BSEU) Local 434, a county employee union that included some social workers, but mostly various other classes of workers employed by Los Angeles County hospitals.

The Social Workers Action Committee’s goals included a pay increase, and reduction in caseloads, paperwork, and worker-to-supervisor ratios. The Committee also had a broader vision: to work together with welfare rights groups, which were emerging from the civil rights movement, to advocate for reform of public assistance agencies. They decided the best way to accomplish these things was to form a separate social workers union. They approached former United Public Workers leader Elinor Glenn, the general manager of BSEU Local 434.

Glenn supported organizing, and appreciated audacity. David Novogrodsky worked with Glenn as a BSEU researcher in Los Angeles in the early 1960s. He recalled that “She had a reputation as being the ‘shit house organizer’ because she would hold her meetings in the women’s bathroom, where the management people, who were all men, they just didn’t feel they could walk through that door.” Glenn was sympathetic to the social workers’ desires, but pragmatically wanted some accountability too. So she issued a challenge to the group: organize five hundred workers and she would help them get a charter for their own union local. After they met her target, Glenn procured the promised charter, for BSEIU Local 535, in August 1964.

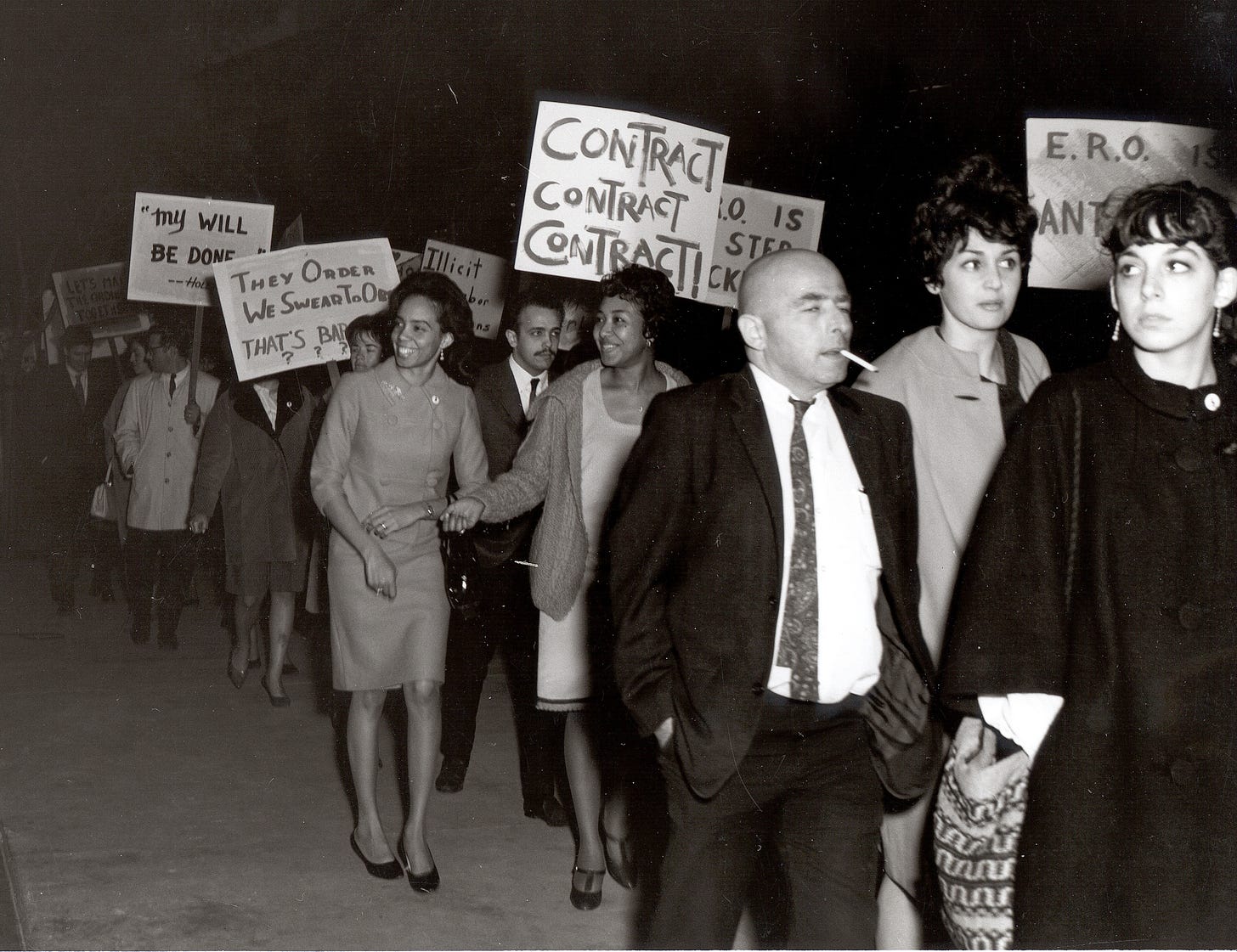

Inside a year the Local 535 membership reached one thousand. The local hired Novogrodsky as Executive Director. In early 1966 he demanded that the county bargain with them: “We wanted bona fide collective bargaining, like they had in the automobile industry.” They asked for the same raise, $100, for all county social workers. In addition, they told the county representatives that the Bureau of Public Assistance should be “liberated” from the Department of Charities. Initially the county representatives agreed to a 10% increase, and to bargain, according to a letter from the Superintendent of Charities, on “everything from caseloads to coffee breaks.” But at the end of May the County backed away from the agreement, precipitating a strike.

It lasted seventeen days, and established a starting salary of $600 per month. A week later, the county authorities once more reneged on the agreement, and attempted to punish strike leaders and activists. The workers went back out, this time until July 4. The local union’s attorneys filed suit and prevailed, reinstating fired strike leaders, and forcing the County to honor its agreement. Within a year and a half the county Department of Charities had been reorganized, with separate departments for county hospitals and public welfare.

A unique form of solidarity

Local 535’s activists were busy with their own activities, but found time to lend their expertise to fellow California workers in need. Soon after the Delano grape strike began, the Kern County welfare department denied benefits to striking farm worker families. Local 535 members, led by Pearl Hazelwood, started up a support committee. It traveled every couple weeks to Delano, where its members steered farm workers through the claims system, a unique form of solidarity only social workers could offer.

The young union, expanding outside Los Angeles, helped Santa Barbara workers strike for higher salaries and a grievance procedure that same year. The following February Sacramento social workers struck to gain collective bargaining rights, and stayed out for the longest public sector strike in United States history: two hundred and eighty days. They were led by Bob Anderson, a Compton social worker who left his agency office during the Santa Barbara strike to help out and never went back.

In late spring 1967, in the midst of the Sacramento strike, social worker union delegates from across California met in the state capital. They were greeted at the airport by strikers and brought to the Sacramento Labor Temple. Here, at a three-day meeting, the social workers established SEIU 535 as a statewide union local, and organized themselves into a joint council together with fast-growing SEIU locals representing other public employees.

The need for a collective bargaining law

The Sacramento strike was difficult (more than two hundred picketers were arrested, and 183 lost their jobs) and unsuccessful, but it drew sharp attention to the need for a collective bargaining law for public employees. It also helped convince workers in other Northern California counties that this was a union willing to fight for them, and they joined by the hundreds: sometimes as individuals, and at other times affiliating entire local employee associations.

Novogrodsky noted, “It shook everything up. Other public workers looked at what happened and said, “If these social workers could do it, so could we.”” Fired Sacramento strikers scattered around the state and went to work for other local social service agencies. Many of these helped organize their new workplaces.

Even with the loss of such a large number of leaders, the Sacramento social workers voted for representation by Local 535 when challenged by AFSCME. Local 535 soon gained chapters in Santa Clara, Alameda, and elsewhere. SEIU picked up other units of Sacramento county workers, although most opted for AFSCME. This rivalry, and worker militancy, became the pattern across the state, as the two unions vied for the allegiance of unaffiliated local associations of public workers.

Legal at last

In 1968 the California legislature passed the Meyers-Milias-Brown Act, formally legalizing collective bargaining for local government workers. Much as the National Labor Relations Act had been enacted in 1935 in response to powerful worker movements, the MMBA put into place rules to channel the militant activism of public workers within legal boundaries. It was almost the “little NLRA” public employee unionists had been seeking for years.

However, the MMBA had limitations. It established local bargaining authority, but not statewide units; it left the details to local determination, and specifically excluded public education and state employees. It also had no enforcement mechanisms, leaving problems to be sorted out with raw power or by the courts. But it did say clearly that public employers had to meet and confer “in good faith,” and agreements had to be reduced to writing, or contracts. As such, according to David Novogrodsky, “It was a license to organize.”

MMBA forced the employee associations to understand there was now no stopping the union train. They had to win elections and to bargain collectively. The law also helped the already existing unions—especially AFSCME and SEIU—to believe they could win elections against the associations. And they won a lot of them.

For more on California’s labor history, you can buy Fred Glass’s From Mission to Microchip: A History of the California Labor Movement (University of California Press) here.

Fred Glass is the author of From Mission to Microchip: A History of the California Labor Movement (UC Press, 2016), a retired City College of San Francisco Labor Studies instructor, and a former member of the State Committee of California DSA.