By Mel Freilicher

The Trouble with Harry Hay: Founder of the Modern Gay Movement by Stuart Timmons on Alyson Publications, 1990

Early on in his excellent biography, the late Stuart Timmons asserts, “No one could have suspected that this patrician will would throw its force behind many of the country’s most radical causes.” Harry’s life was dedicated to left-wing activism. A member of the Communist Party USA from 1935 to the early ‘50s, when he finally decided to advocate for gay rights above all else, he was forced to quit the Party, and was painfully shunned by many former friends and colleagues.

Hay himself attributes his founding of the Mattachine Society, one of this country’s first, and certainly most generative, homophile organization as a product of “total allegiance to high purposes, tenacity of vision, irrevocable resolve, and above all else, audacity.” Hay’s “most astonishing achievement,” Timmons comments, was “a thing that was nearly inconceivable for the first half of his life.”

The author does an excellent job of explicating the forces in Harry’s privileged life which led him to these consequential decisions. Timmons first met Harry in 1980, when he was age 68, and this volume is so effective because much of it is taken from extensive personal interviews.

Harry Hay’s highly successful father was a stone-faced, massive, peripatetic mining engineer with a degree from Berkeley. Working in New Zealand, then for the British financier and colonist Cecil Rhodes in South Africa, and on the Gold Coast, he was offered a high management position in the Guggenheim family’s Anaconda Company in the Andes of northern Chile.

There, in 1916, from an elevated trestle track nearly l00 feet above him, a one-ton carload of ore suddenly fell on Big Harry. He lost his right foot and leg below the knee, and for further treatment the family set sail for southern California where they bought a house and 20-acre orange orchard in Orange County.

Although Big Harry regained much of his strength, and learned to drive a car again, his disability aggravated his authoritarianism. The more he failed in physical struggles, the more he turned angrily on his namesake: enforcing a code of perfection with verbal attacks and frequent beatings. Harry sometimes said he lived his life in deliberate opposition to his father, and even his politics were motivated by a “personal hatred” of the man.

Once settled, their parents prepared the Hays siblings to participate in the Beverly Wilshire Country Club dances for children of the elite. These formal soirees required evening gowns and corsages for the girls, dinner jackets and pomade for the boys. Parent-chaperones included Mrs. Harvey Mudd, Mrs. Doheny, Mrs. Chandler, and Mrs. Harry Hay.

Harry’s mother, who’d relied heavily on nannies for her children’s upbringing, was forced to give up some of her dreams for her precocious son, like a private education in Switzerland then the University of Heidelberg. While Big Harry’s ancestry was upper-class Scottish highlander, Margaret Neall’s pedigree was more refined: her family included Corcorans (of Washington’s Corcoran Gallery of Art), Anna Wendell (an aunt of Oliver Wendell Holmes) and the van Rensselaer family.

Although deeply involved in family life, Harry felt distanced from his parents, and closer to an aunt and uncle. Aunt Kate, his mother’s aunt, was an independent schoolteacher in Virginia City, Nevada who spent long periods visiting the Hays, and taught Harry how to read. She was the only member of the extended family who stood up to the Hays’ staunch Republican views.

Margaret’s brother, Jack Neall, a dashingly handsome lifelong bachelor, served in the Royal Air Force during the War. Having studied chemistry, he nevertheless led a dilettante’s life of “investments, art, and the company of theater people,” including theater owners like the Belasco’s and the Pantage’s. Also living with his family for extended periods, Harry absorbed his lectures in music, theater and art. But later in life, he pegged his uncle as a “gay snob.”

Taking great delight in hiking the pastel-toned San Gabriel Mountains, every summer Harry reached far-flung campgrounds where he honed his outdoor skills. Participating in a boys’ group, the Western Rangers, not only sharpened his homoerotic feelings, but introduced him to a lasting relationship with Native Americans. “The first male brotherhood Harry joined, with its emphasis on personal ethics and natural harmony,” Timmons comments, “foreshadowed his models for the Mattachine Society and, later, the Radical Faeries.”

Harry used to haunt the public library. At 11, by stealing a key to a locked cabinet, he came across Edward Carpenter’s remarkable, The Intermediate Sex. Aware of his own sexual impulses from an early age, this 1906 work offered Harry a unique view of homosexual identity: “a genteel but forthright discussion of people with ‘Uranian temperament’ and ‘homogenic attachments’ between them.”

“My father tried to beat the sissy out of me,” so Harry was sent to work summers at his cousin’s farm in western Nevada. At first the work was exhausting, but he was helped by his partner, a middle-aged Washoe Indian named Tom. Bonding with the field hands, Harry always managed to avoid their whorehouse excursions. Meanwhile, he discovered a cache of opera records owned by his cousin’s mother, and spent hours listening, and discussing them with her.

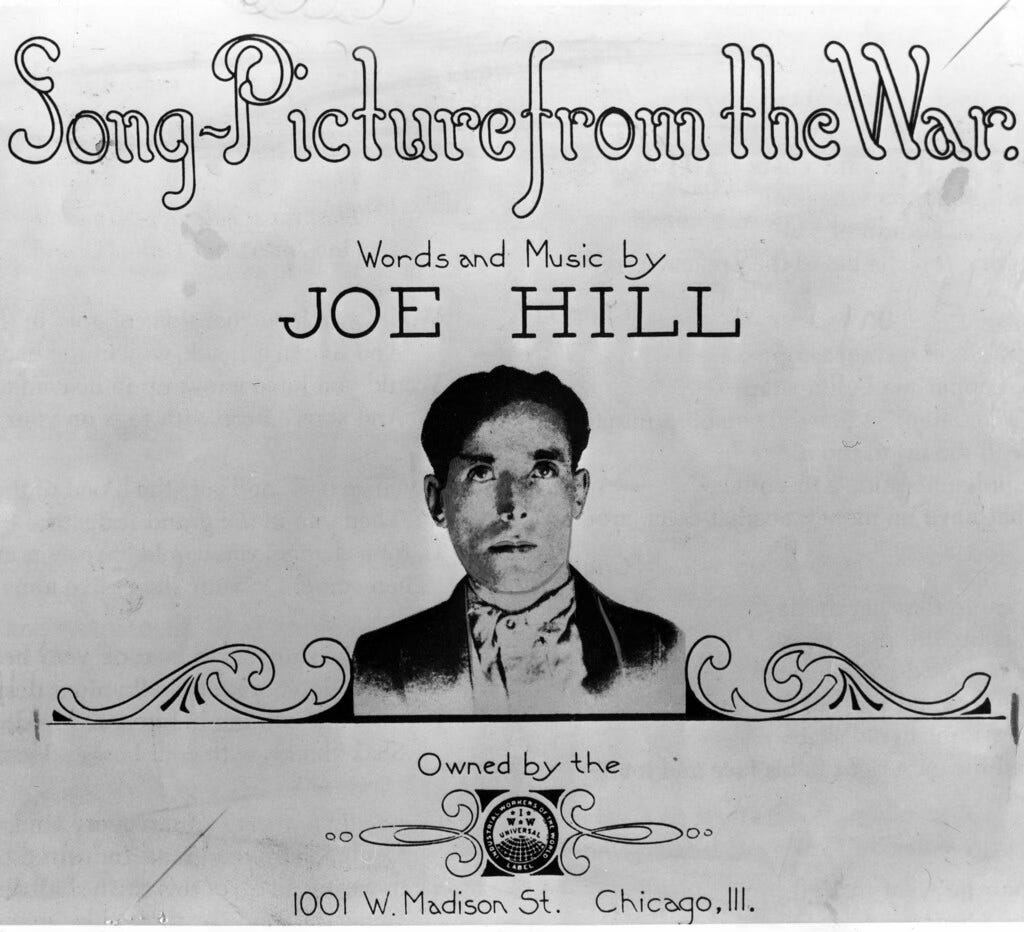

Timmons tells us, “The most complete subversion of Big Harry’s scheme was in becoming a socialist.” Although homophobic, many of the farmworkers were Wobblies, and veterans of IWW’s turn-of-the-century labor movement. They had known the great songwriter Joe Hill, martyred ten years earlier, and taught Harry some of his songs. On the hay wagon, they tutored him in Marxist literature. By day, they drilled him in principles of exploitation, organization, and unity.

By campfire, they told Harry stories about their involvements in the Haymarket massacre, the first great railroad strike of 1887, the Ludlow, Colorado massacre where Rockefeller goons gunned down 14 women and children in the strikers’ camp on Christmas Eve, 1913. This political baptism made a powerful impression, “and for decades afterwards Harry politicized young people by telling thrilling historical tales.”

At the end of his second summer in Smith Valley, the Wobbly field hands gave Harry an IWW card and directed him to the Embarcadero union hall in San Francisco. The card allowed him to sign up with one of the tramp steamers bringing cargo to coastal towns which lacked harbors. Harry was 14, but at six-foot-three and 175 pounds, he easily convinced union officials he was 21.

Docked at Monterey Bay, Harry drank with the crew at a saloon, but again managed to avoid the obligatory whorehouse excursion. Retching, back on the steamer, he was dimly aware of a sailor helping him to his bunk. The next day, Harry learned that sailor was a merchant marine who’d already traveled to ports in Asia, Africa, and Europe.

In a grove of trees, this “gracefully muscled young man of about twenty-five with dark coloring” became Harry’s first lover. Afterwards, when he unthinkingly admitted he had little experience because he was only 14, Matt jumped to his feet in panic, explaining he could be sent to jail. But Harry persuaded him to stay—to hold him and talk.

Matt told Harry they were members of a “silent brotherhood” which reached around the world. “’Someday, you will have wandered to a strange and faraway place…And then suddenly, in that frightening and alien place, you’ll look across the square and you’ll see a pair of eyes open and glow at you. You’ll look back at him, and at that moment, in the lock of two pairs of eyes, you are home and you are safe.’”

In later years, when Harry told this story, he declared, “’I molested an adult until I found out what I needed to know.’” He always described his coming out experience as “’the most beautiful gift that a fourteen-year-old ever got from his first love.’”

Attending Stanford for less than two years where he had a brief affair with James Broughton, future poet and filmmaker, Harry became increasingly interested in theater, though his major was international relations. In his second year, Harry felt compelled to come out to virtually everyone at school, the only student that did so--isolated, he left soon afterwards.

In the first half of the ‘30s, working in Hollywood, Harry was busily cruising, often multiple times a day. He began an intense affair with Will Geer, a 30-year-old actor who’d already spent half his life on stage, and later became famous as “Grandpa Walton.” Geer was known around town as a radical activist, producing fundraising events on a regular basis, sometimes in conjunction with the John Reed Experimental Theater.

It was Geer who introduced Harry to the left-wing community of Los Angeles, and eventually to the Communist Party. He plunged Harry into hard-core activism: demonstrations for farmworkers, the unemployed, labor unions in need of lawyers. One incident which Harry recounted in great detail was “the Milk Strike” of 1933, an action by the wives and mothers of the unemployed to make the government stop allowing surplus milk to be poured down the drain in order to keep prices up.

A crowd of thousands turned out downtown in the shadow of the newly built City Hall. Seeing machine guns atop buildings, and quite aware of the violence often used against demonstrators, Harry backed away when mounted police, swinging their nightsticks, charged through the growing crowd. “’The police were absolutely brutal,’” Harry recounted, “’without provocation. I think they may have wanted to start a riot.’”

Backing up to the open door of a bookstore, where stacks of newspapers were held down by bricks, Harry recalled, “’I made no conscious decision, I just found myself heaving one and catching a policeman right on the temple.’” He was the most amazed of anyone. “’I had been the one who threw the ball like a sissy. This “bull” was my first bull’s-eye ever!’”

Timmons describes the scene vividly. “Sympathizers murmuring in Yiddish, Portuguese and English grabbed him…and led him backward through a building connected to other buildings—a network of 1880s tenements that formed an interconnected casbah on the slopes of the old Bunker Hill quarter. He was pushed through rooms that immigrant women and children rarely left, across catwalks and planks, up, up, hearing the occasional reassurance.”

When they emerged at the top of the hill, Harry was led into a large Victorian house, where he found himself in a living room full of men drinking coffee. “In the center, gesturing theatrically, cutting a cake, was a soft-featured man with hennaed hair that was pinned up, and wearing a blouse that was pulled down around one shoulder, gypsy style.”

Harry already knew the man who everyone addressed as Clarabelle was one of the most powerful “Queen Mothers”: figures forming a regional district of salons among pre-Stonewall gays. “Clarabelle controlled Bunker Hill and had at least a dozen ‘lieutenants’ covering stations including the Fruit Tank jail cell for queers.”

She ordered a lieutenant to hide Harry from the police in the basement in a carpeted cave storing Persian rugs, and he was promised a fried egg sandwich and coffee. “’After several hours,’” Harry recounted, “’someone finally brought me coffee. It turned out to be Clarabelle’s nephew. A cute, sort of V-shaped young man who just loved sixty-nine. He stayed for hours. I never got the egg sandwich, but I didn’t much care.’”

Harry credited the first step in his radicalization to the weekend he spent with Geer in San Francisco during the General Strike of 1934. Centered on a maritime strike which shut down the waterfront, the action lasted 2 months and involved 120 unions. Harry was there when the state militia, called in by Governor Frank Merriam, opened fire on a crowd of more than 2,000. Two men were killed, 85 hospitalized.

At the massive funeral procession which followed, Harry recalled, “’As the two flag-covered caissons passed, drawn by horses slowly high-stepping to the funeral music, a posse of dock workers knocked the bowlers off the heads of bankers who refused to show respect. It was pretty damn impressive.’”

In 1936, Harry and Geer were involved in organizing, and acting in, Clifford Odets’ play, Waiting for Lefty. Just before the California opening at the Hollywood Playhouse, Will Geer was attacked by Los Angeles Nazis. Subsequently, Harry became involved with the Hollywood Anti-Nazi League (which, while independent of the CP, relied heavily on its membership), Upton Sinclair’s EPIC (End Poverty in California) campaign, the American League Against War and Fascism and many other organizations.

With numerous flings and boyfriends, Harry’s social life was often focused on the newly formed Hollywood Film and Foto League, housed in a former White Russian nightclub with a huge dance floor, stage and murals of giant flowers in Russian folk décor: whitewashed so experimental films, like Eisenstein’s Ten Days that Shook the World, could be projected each weekend. More than a dozen dancers, sculptors and other artists pooled their relief checks for rent and communal meals. Some identified as Reds, others were completely apolitical; gays and straights casually intermixed.

Sometimes denizens of the League would go to hear Harry play the organ for the L.A. lodge of the Order of the Eastern Temple, Aleister Crowley’s notorious anti-Christian spiritual group which met in the attic of a 4-storey house. Crowley’s not-so-secret society was known to have created homosexual magic rituals, first described in his 1912 tract, Eroto-Comatose Lucidity. A common form of the ritual used sexual stimulation, but not to orgasm, to place the individual in a state between full sleep and wakefulness as well as exhaustion, allowing the practitioners to commune with their god.

By 1938, Harry made a firm commitment to the Communist Party. Initially, the Bolsheviks legalized homosexuality after the 1917 revolution, but their position changed drastically. Describing homosexuality as a “social peril” in 1928, in 1934, Stalin criminalized such acts as part of a broad policy of “proletarian decency.”

Dismayed by the CP’s rejection of homosexuals, Harry brought up the idea of a “team of brothers” to Geer who would not consider it, arguing the concept was theater, not politics. Over the next 20 years, whenever Harry periodically proposed the idea of a gay political identity to anyone, he rarely got encouragement.

Harry Hays’ marriage lasted from 1938 to 1951. Timmons claims it “confounded many of his later gay comrades” when they learned about it, and was caused by a “complex mix of political and emotional reasons…Paramount was the inability to find a male lover who tolerated the progressive movement—and a progressive movement that would tolerate his having a male lover.” (Will Geer married too, and James Broughton married twice.)

Harry’s wife, Anita Platky, a Jewish Party member, also involved in theater, assured him she understood about his homosexual past. They did Party work as a couple, often within the Film and Foto League. With no training and only a brownie camera, they undertook a photo exhibit on poor housing conditions in racially restricted L.A. slums such as the Chavez Ravine. One picture showed the single faucet outdoor cold-water pipe that supplied 24 houses.

Moving to New York for a year, and joining the local CP group, Harry worked as interim director of the left-wing New Theater League and also taught acting classes to members of the Longshoremen, Cooks and Stewards, and Bus Drivers unions. While frequently cruising in Central Park, for over 7 months he was seriously involved with a cultivated, rising young architect, William Alexander, a nephew of Frank Lloyd Wright, almost leaving Anita and the Party.

Back in L.A., Harry found work with the Russian War Relief, then held a steady stream of jobs, including in a foundry making airplane parts. He and Anita socialized with many progressive couples, not all of whom were Party members; discretion was necessary. The couple attended as many as 9 CP events in a week.

Supposedly, the first two years of their marriage were passionate (though Harry increasingly relied on fantasies about male partners) but the couple couldn’t conceive. They adopted two children in the ’40s. On many family camping trips, Harry “lectured for hours in terms that we could not understand,” according to both his daughters, Hannah and Kate. Timmons claims, “They were a family both happy and troubled.”

Hannah ceased communication with her father in the 1970s over what she termed his “’tormenting gay chauvinism,’” but many of her memories were tender. He took her biking, showing her the beautiful spots of his childhood. “’He used to carry me out at nighttime…and tell me about the stars and what was going on in the sky—the relations in the universe. He made the moon very special to me.’” Harry instilled love of nature in his children, and a reverence for animals.

The 5 years beginning in 1946 with the adoption of Hannah ending with his divorce were Harry’s “period of terror,” a sort of prolonged, stifled breakdown. His often recurring nightmares worsened, and disturbed him deeply. “’While Anita and the kids were away at Catalina once,’” he recalled, “’I had dreams of blacking out and hurting them…I was confronted by the horror of my own existence, I didn’t know what to do.’”

In the last years of married life, Harry was preoccupied with a leftist mass organization called People’s Songs. So taken with folk music that, according to a friend, Harry “became the theoretician of People’s songs,” in keeping with the Marxist practice of creating a theory for everything. He began to teach courses in the historical development of folk music which sometimes featured left celebrities like Pete Seeger and Malvina Reynolds. Harry was already a prominent, very successful teacher of Marxist economics throughout the L.A. region.

In 1948, he first formulated what later became the Mattachine Society, partly inspired by the recently released Kinsey Report which claimed that 37% of adult men had experienced homosexual relations. The writing of “the Call,” as Harry referred to the organizational prospectus ever afterwards, began his dedication to a life of gay activism.

The original was drawn up in 1951 and lost several years later. But a revised edition still survives. At the end of the first page, he proclaimed a formal incorporation:

WE, THE ANDROGYNES OF THE WORLD, HAVE FORMED THIS RESPONSIBLE CORPORATE BODY TO DEMONSTRATE BY OUR EFFORTS THAT OUR PHYSIOLOGICAL AND PSYCHOLOGICAL HANDICAPS NEED BE NO DETERRENT IN INTEGRATING 10% OF THE WORLD’S POPULATION TOWARDS THE CONSTRUCTIVE SOCIAL PROGRESS OF MANKIND.

Some of this wording would change radically: the term “handicap” was soon banished.

After two years of dead-end planning with other progressives to join him, Harry found support from an unexpected turn of events—he fell in love. His relationship with the young Rudi Gernreich changed everything, “bringing an end to his marriage, terminating his membership in the Party, and relieving his deep psychic distress.”

On the surface, the marriage ended amiably. But, Timmons reports, Anita “struggled with feelings of betrayal. Divorced at age 38, she never remarried. Hannah, the eldest daughter, described the dissolution as a ‘scandal’ and an ‘abrupt jilting’ not only of her mother but for the entire family.”

Leaving the Communist Party was handled cordially on an official level, but many of Harry’s former friends and colleagues turned against him. “’I would go to various events around town,’” Harry recalled, “’and people would cross the street to avoid speaking to me…Going to speak to someone…I’d get this cold, closed-down, almost “how dare you” look. I’d feel like such a leper.’” This “wrenching feeling,” Timmons emphasizes “was doubled by the fact that bonds within the Party were based on a deep, idealistic companionship that Harry had enjoyed for a decade and a half.”

Friends remember Rudi as a dazzling combination of intelligence, looks and elan. One said, “He was bright, witty, and had the most subtle sense of humor.” Having come from Vienna as a 16-year-old Jewish refugee in 1938, he could still “make double entendres in English without batting an eye. Everything he touched has a little something extra—that spirit was in his dancing, his speaking voice, the clothes he designed” (first known for his hats).

While encouraging Hay’s undertaking, Gernreich counseled extreme caution and discretion, both for the sake of the individuals and the stability and potential of such a movement. Before leaving Europe, Rudi had been aware of the homophile movement led by Dr. Magnus Hirschfield, whose well-known Institute for Sexual Research had been easily smashed by the Nazis: its records sent homosexuals to death camps.

For years, Rudi was the Mattachine’s mystery man. In accordance with the Society’s oath of secrecy, Harry never revealed the cofounder’s identity. This necessity was underscored when Gernreich achieved world fame as a designer in the sixties and seventies with such fashion breakthroughs as the early use of vinyl and plastic, the topless bathing suit, unisex look, and shaved heads.

Rudi’s “coming out” was posthumous. After he died of lung cancer in 1985, the ACLU announced the estate of Gernreich, along with his surviving life partner, Dr. Oreste Pucciani, had endowed a charitable trust to provide for litigation and education in the area of lesbian and gay rights.

When they decided to turn their “concerned citizens” front group—mostly composed of men who had some association with the Communist Party-- into a state-registered nonprofit organization called the Mattachine Foundation, Harry’s mother agreed to be president of the board of directors, though it was doubtful she comprehended its purpose. Several other female members of the cadre’s families also served on the board: thus gay people had a channel for dealing with the public and with officials, but at a reduced risk.

Several Mattachine members helped start the first widely distributed gay publication in America, ONE Magazine: The Homosexual Viewpoint, inspiring the creation of others. The Foundation provided ONE with its mailing list, and seed money. The magazine sported elegant layout, strong graphics, fiction, intellectual and cultural activities and essays, often but not always printed under pseudonyms.

ONE recounted details of entrapment arrests and harassment of bars, also documenting other measures of oppression. After the Miami city commission ruled alcoholic beverages could not be served to homosexuals, and two or more gays could not congregate in a business establishment, the magazine reprinted one gay bar’s spoof of the law, including the dictum, “Male customers may NOT wave at friends or relatives passing by the street because we’ll have none of those gestures in here, my dear!”

Never reported in the mainstream press, Mattachine fought and won a sexual entrapment case, for the first time ever. To entrap gay men, officers engaged in various practices, from discreet glances to the point of full participation. (A joke from the time went, “It’s been wonderful, but you’re under arrest.”) Few lawyers would take these cases, and those who did invariably counseled a guilty plea, charging a fee ranging from $300 to $3000.

Harry knew dozens of men whose lives had been marred by the practice, some went into permanent decline following arrest. Often men convicted of “lewd-vag” paid large fines rather than spend time in jail where they could be singled out for beatings and rape. The dilemma, Harry recalled, “’made everyone plead guilty, and plea bargaining was not yet in practice. So to the average ribbon clerk this could mean years of debt.’”

At an emergency meeting concerning a Mattachine member, Harry declared, “’Look, we’re going to make an issue of this thing. We’ll say you are homosexual but neither lewd nor dissolute. And that cop is lying.’” The Foundation set up the Citizen’s Committee to Outlaw Entrapment: raising money for legal defense, and public awareness through a series of fliers addressed to “the community of Los Angeles,” emphasizing the perils of guilt by association, and detailing the bitter harvest of entrapment.

When Harry was called to testify before HUAC, witnesses against him included an agent who had been sent to Harry’s classes, who he regarded “as one of my more devoted if stupider students.” A woman who’d been a babysitter for many of his leftist friends had gone through their private papers, and testified that Harry was “a Soviet agent.”

Harry severed his case from the others subpoenaed, retaining his own lawyer. Firing of federal employees, the “Lavender Scare,” was in full swing, and Harry didn’t want to implicate other Party members in any gay baiting. Regarding Party activities, he pleaded the 5th, but was prepared to answer directly if asked about his homosexual organizing activities.

He wasn’t questioned about Mattachine, but his name had already been dropped in the May, 1954 Confidential magazine, the lurid scandal sheet of the decade, which fervently trashed social deviation and political dissent: he’d been labeled a “pinko” under the headline “America on Guard—Homosexuals, Inc.!”

Although Harry’s employer at the time somehow missed the newspaper accounts of his testimony, homophile organizations pushed him away. After 3 years of intense Mattachine work, the group felt the need to distance itself from the taint of communism. Rudi had already moved on, and Harry’s new partner was eager to lead a safe, bourgeois life: their morose, alienated relationship lasted 11 years.

During that period of political inactivity, the couple traveled extensively in the American Southwest. Continuing his research, convinced gay culture had always existed between the lines, Harry investigated, and wrote about, the berdache, a term given by the French to Native American crossdressers. Although ONE did publish several of these articles, after his HUAC testimony, Harry commented, “I wasn’t even notified about anything more ONE did, let alone invited.”

Harrys “final coming out,” as he called it, in 1963 was marked by the beginning of his lifelong relationship with John Burnside. Hay began wearing his hair longer, brighter clothes, and a necklace or earing muted in tone but bold in shape. “I decided I never again wanted to be mistaken for a hetero,” he explained. "Ever.”

John Lyon Burnside III had studied physics and mathematics at UCLA, worked as an engineer in the aircraft industry, winding up as a staff scientist at Lockheed. When he and Harry met, Burnside had already dropped out of the system and was manufacturing his own optical invention which worked like a kaleidoscope but turned whatever was in front of its viewfinder into a symmetrical mandala.

Realizing he was gay at age 14, one unfulfilling experience and “his distaste for the limitations of gay life as he then saw it” led Burnside into an early marriage which he described as “not unhappy.” But his inner life was “cursed” until he began to go to ONE meetings, which he’d heard about from some of his gay employees. After some awkward months, Burnside left his wife and moved into Harry’s apartment.

Outsiders sometimes assumed Harry’s masculine demeanor and their relative stature (Harry was half a foot taller) reflected butch-femme roles in their relationship, but Harry had consciously abandoned that model. At parties they attended, most male couples were attired one in a suit, the other in a flowered shirt; Harry and John both wore flowered shirts. Invited to appear on “The Joe Pine Show,” hosted by a well-known TV muckraker, they wore identical outfits: blue yachting tops with vermilion pull-overs.

To combat their notoriously aggressive host, Harry brusquely began many of his sentences, “Look. Pine,” as he jabbed his finger. To an inane question about “How could you guys control yourselves in the Army?” Harry retorted that homosexuals “had to learn to control ourselves so we could get through high school with a full set of teeth”; the exchange was so lively they were asked to come back to do a second taping.

Meanwhile, Harry became involved with newer, early ‘60s gay groups (the older ones had more or less imploded). In 1965, he founded the Circle of Living Companions a politically active collective which remained part of his and John’s life for decades. For Harry, the name symbolized how all gay relationships could be considered on the Whitmanesque ideal of the love of comrades.

Membership was based on affinity, and over the years the Circle encompassed different close friends, such as the lesbian couple, Del Martin and Phyllis Lyon, who started the publication, The Ladder, and in 1955 had founded The Daughters of Bilitis in San Francisco, the first lesbian civil and political rights organization.

In August of 1966, the recently formed North America Conference of Homophile Organizations (NACHO) convened in San Francisco, and conducted marches in several cities, focusing on the military’s exclusion of homosexuals. Though his politics did not exactly favor military service (within a dozen years he would establish a Gay Draft Counseling Network in his living room), in a campaign to illegalize the oath required of inductees that they were not gay, Harry argued invasion of privacy.

Once Stonewall exploded in ’69, everything changed. By December, Harry and John participated in the founding meeting of the Southern California Gay Liberation Front, one of the many regional counterparts to the militant New York organization. Harry was elected its first chair.

Harry and John founded the Radical Faeries in 1979, a spiritual, back to nature group which influenced many young gay people. For Harry, “the affiliation of faeries provided a deep-seated resolution to his tenacious search for a genuine gay community.” At rural retreats, a carved talisman would be passed around a Faerie circle and where it stopped the group’s undivided attention focused. As Timmons describes it, “The green meadow, the blue sky, and their very bodies seemed to glow as each shared early memories of feeling different.”

At the end of a session, the circle closed, the men came together, “arm in arm, body to body, and a deep om began to sound, vibrating through the huddle of men, each more completely a living part of the circle. Male voices rose in humming harmony, and the sound gained momentum, like dozens of fingers on wineglasses. As they dispersed, flute music played as if from a sylvan track. Accompanying voices sang: ‘Dear friends, queer friends, let me tell you how I’m feeling/You have given me such pleasure, I love you so.’”

No matter how many years an individual had been out of the closet, Timmons claims “they felt that until they found the Faeries, something had been missing.” A professor at Hamilton College who’d always felt inhibited, trapped in an over-abstract intellect, called the Radical Faeries a lifesaver. An early participant in ”faerie circles” attempted to explain his experiences. “What Harry did was give thousands of gay men the space to get over the most painful wounds that this society could possibly inflict on them.”

Timmons views the Faeries as responsive to the emptiness of both the straight establishment and assimilated gay lifestyles. “Those who flocked to the gatherings had found little distinction between the two—to them, both were oppressive, shallow and mired in such macho values as male competitiveness and dominance.” Specifically, newly emerging gay ghettoes of the ‘70s were promulgating and commodifying the “clone” look, close descendant of the straight-identified “faggot”: muscles, mustaches, mirrored “cop” sunglasses, bomber jacket, and boots “became a veritable uniform.”

Some “clone weary” gays retreated from urban life. Though hardly constituting an organized group, rural gays established several collectives: one of the most lasting was the RFD collective, founded in Iowa in 1974. When the countercultural Mother Earth News refused to run an ad with a gay reference, the seven member group began a homespun publication, RFD: A Magazine for Country Faggots. Contributors, including multiple pieces by Harry, and readers of RFD overlapped substantially with gays who would soon be calling themselves Faeries.

At first, Harry avoided calling it a “movement.” He saw the group as a networking of gentle men devoted to the principles of ecology, spiritual truth and gay-centeredness. But, as Radical Faerie groups sprang up internationally, a “shock” to Harry, inevitably, schisms developed—not dissimilar to what occurred in the women’s movement—largely between those favoring a spiritual movement and those who wanted to direct their energies outward toward politics.

One participant, a former activist himself, is quoted: “I always resented Harry bringing in things from the outside world. What a lot of us wanted was to shut out the world again and be a tribe and discover who we were.”

The Radical Faeries became well known partly due to two groundbreaking works: Peter Adair’s documentary, Word Is Out, and Jonathan Katz’s 1976 study, Gay American History. Katz’s seminal work is dedicated to Hay and Jeanette Howard Foster, author of Sex Variant Women in Literature “For my people, with love, in struggle—and in honor of two pioneers.” Learning of the dedication, Harry was “breathless with surprise and pride at the honor.”

Another key historian, John D’Emilio, researching the homophile movement, published a complete account of its history. When the Mattachine chapter was previewed in three parts in the influential Canadian newspaper, Body Politic, Harry’s legend was launched for the gay lib generation.

Harry Hays’ life is both legendary and a piece of history. He died in 2002, at the age of 90.

Mel Freilicher retired from some 4 decades of teaching in UCSD's Lit. Dept./ writing program. He was publisher and co-editor of Crawl Out Your Window magazine (1974-89), a journal of the experimental literature and visual arts of the San Diego/Tijuana region. He's been writing for quite some time. He is the author of The Unmaking of Americans: 7 Lives, Encyclopedia of Rebels, and American Cream, all on San Diego City Works Press.