Top 5 Need-to-Knows About “Pulling the Plug” on Dad

Navigating a Dehumanizing Healthcare System During End-of-Life

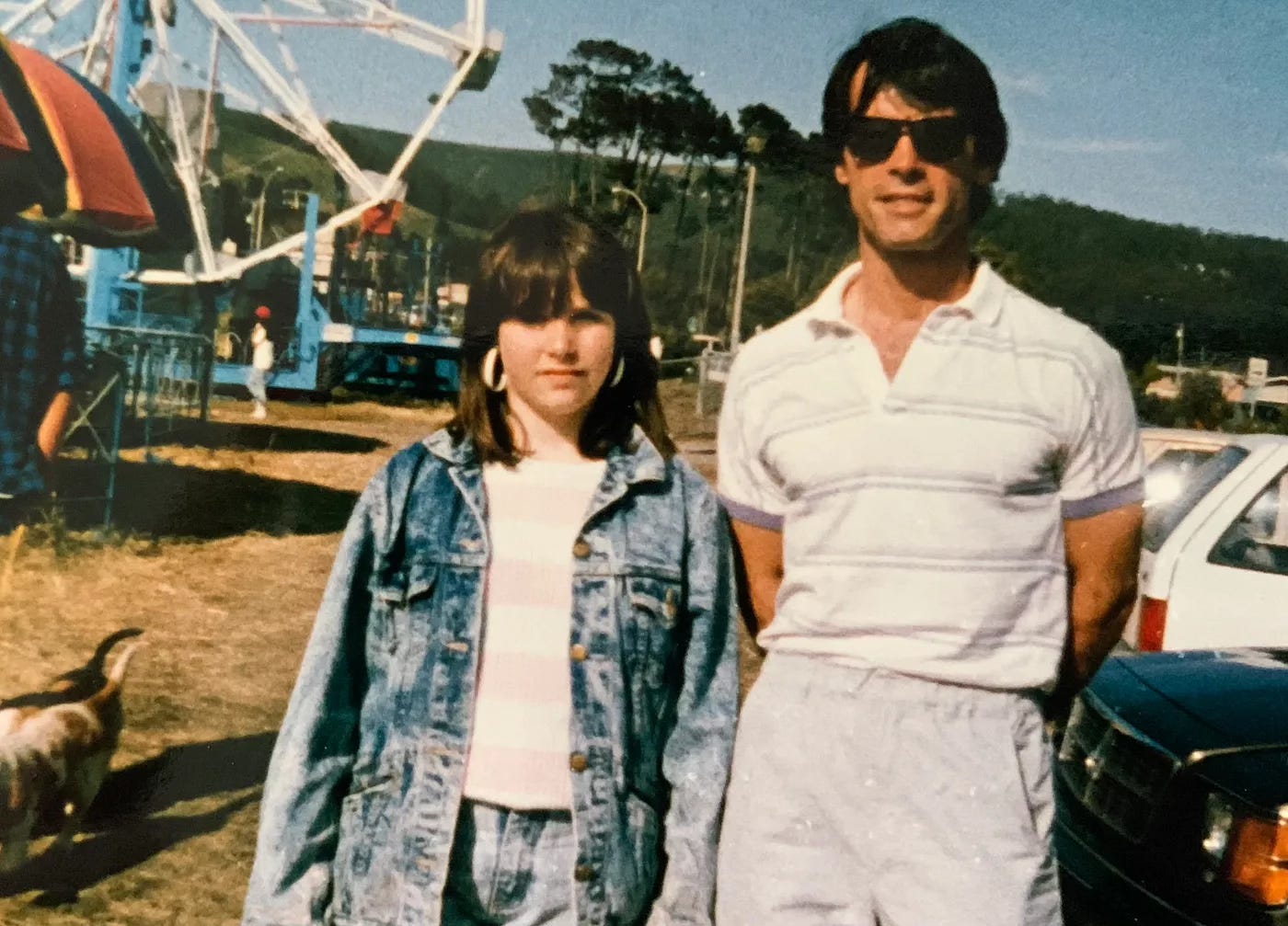

By Erin M. Evans

Need-to-know #1: Make jokes like it’s not totally inappropriate.

That title is only funny to me, and that’s ok, which is my first item of advice if you’re going to be responsible for carrying out a loved one’s end-of-life decisions. This life can get so hard sometimes that it feels like your heart and lungs are sinking into your guts. When that happens, as it does when a loved one dies within a deeply flawed, market-based healthcare system, I suggest that you make jokes. Any joke, even if it’s the title of a “listicle” you’re writing to digest what you experienced. I hope you’ll read on without thinking that I take my Dad’s death on Thanksgiving Day in 2020 lightly. I don’t… mostly.

Need-to-know #2: Be Prepared to be totally unprepared.

Dad and I talked a lot about death after he was diagnosed with congestive heart failure in 2010. He never hesitated — “No life support.” He spent a full month in an ICU in 2017 and it was cut even further into stone for him. He didn’t want “the downward spiral to last forever,” and he said he would refuse to depend on anyone for his most basic needs, not even a live-in nurse. Being that vulnerable and (according to him) “useless” would be the death of his sense of self, which felt (for him) worse than physical death. Does that seem clear to you? Because it is not.

Movies and television poison us with unrealistic “pull the plug” scenes. The term “life support” itself reflects our addiction to binaries like alive or dead, male or female, us or them.

“Life support” is not an on/off switch. It is a spectrum of physiological measures used to keep a person’s body functioning. When my dad said he didn’t want the downward spiral to last forever, he was referring to some of these physiological measures that aren’t ventilators or heart pumps, but they are forms of “life support” none the less. They include repeated surgical procedures, medicines, lifestyle changes, and myriad therapies that can be physically painful and mentally tortuous.

He was already on a ventilator and unconscious when I left San Diego for the 9-hour drive to Napa, where he lived with his partner, Judy. It was well into the first year of COVID-19 and visitation was extremely limited. Judy and I went straight to the hospital after I arrived, and we were allowed to visit him only because he’d gone into another cardiac arrest a few hours before I got to Napa. The ICU doctor was waiting for us outside my Dad’s room. He was tall. Super tall. Maybe he only seemed that tall because I was feeling about 10 years old, walking through the hospital, looking for my Dad. With the mask on, the doctor’s face was just two huge eyes framed in thin wire glasses. He explained that Dad had gone into cardiac arrest twice and his blood pressure wasn’t responding to medication. Dr. Big Eyes said that another doctor on staff–the cardiologist– placed another stint in his heart after the second cardiac arrest, but that given his kidney values, Dad’s prognosis was questionable and he would definitely be on oxygen the rest of his life.

I didn’t think this moment would happen so fast. I started blathering on, “He is absolutely DNR and that defibrillator in his heart needs to be shut off. And, and… he has a really bad gag reflex. I can’t believe he consented to being intubated. That was his number one ‘NO’ because of how bad his gagging is. He, I mean, he couldn’t even brush his tongue without…”

Dr. Big eyes interrupted my rambling. “Our number one priority, regardless of whether you like it or not, is that he is comfortable. He is comfortable now and we’ll continue to keep him comfortable if you choose to stop treatment. We keep the patients comfortable regardless of whether it’s requested or not.”

I didn’t know how to respond. The ICU was inconveniently quiet. It felt like everyone was staring at me, like I was the center of attention because I was thinking about killing my Dad.

“Why are we all standing here? Am I supposed to pull the plug now or something?”

I pictured the nurse laughing at my sarcasm under her mask. That helped me not panic. “Of course,” he said, “We’ll be starting rounds soon and I’ll ask that we include you, ok?” I nodded and he led us to his bed.

Dad seemed to react when I said “Hi Dad” and grabbed his hand. It was so cold. His hand was really, really cold.

“He’s not feeling any of this, right?”

His nurse reassured me that he wasn’t. A part of me still wants to think that Dad knew I was there. A bigger part hopes he didn’t at all. No part of me was glad or relieved that he was alive like that. None. About ten minutes after we sat next to my dad and started holding his hand, the other doctor, the cardiologist who performed the emergency heart surgery on my Dad, walked in. Let’s call him “Dr. A**hole.”

“He’s responding to the medication and he’s been more stable the last hour. We’ll definitely know more after just a few more days.”

No beats skipped and I said to Dr. A**hole, “That is the f&*king complete opposite of what the other doctor just told us, dude.”

Judy jumped in, “I’m sure you can explain to us why your prognosis is so different from the other doctor?” She used a skillful combination of passive and aggressive. The good cop to my bad cop, if you will. A person to calm me down because it felt like I was deciding between killing my Dad or letting him suffer for dubious ends.

Need-to-know #3: Being the person who will carry out your loved one’s wishes means having an exhaustive number of conversations about dying that you will eventually act upon. It is not your “decision.”

I mentioned before that the framework through which we think about “life support” is based on a culturally entrenched contradiction between living and dying. Choosing the conditions of our death rings acrid in the backs of our ears. Choosing to have your loved one undergo futile and painful medical treatment rings with martyrdom, as if we are enduring these procedures with them. To “live” is to “win” in our Darwinian social construct. This illusion is endemic to medicine and if you don’t stay anchored to a person’s final wishes, it’s very easy to sleepwalk into the illusion. How do we do that, in practice?

Having uncomfortable conversations with our loved ones about death is how we do that. Not interviews. Not yes or no questions. You have to speak and interact with them. If those conversations aren’t uncomfortable then you are not doing it right. Feeling discomfort means that you are having a meaningful conversation about when your loved one would choose death over life.

You can’t just ask, “would you want to be on life support?” Even people who say “no” without even having to think about it won’t say no when they are alone in an ambulance and can’t breathe. I promise you they will not say “no” to being able to breathe. Have you ever experienced suffocation? I feel pretty confident that every person consents to being intubated when they are scared, confused, and suffering. You cannot advocate for yourself when you cannot breathe. You can’t think beyond breathing when you cannot breathe. When you can’t breathe you can’t say to someone, “I don’t want to be intubated but I also do not want to experience this excruciating and panicked agony that I’m experiencing right now. What are our options here?” That is not how a medical crisis works. That is why we need to have uncomfortable conversations and why we engage in the art of knowing each other, deeply.

Dad told me I would be responsible for his affairs shortly after he was diagnosed with early stage congestive heart failure. I am the type who needs to jump into action when a crisis hits to soothe myself. My way of doing so in this situation was to start asking questions. Constantly. When we were watching a movie and a character went into a coma I’d ask, “Would you wanna stay in the coma if you knew you’d be ok within a year?” It wasn’t constant, but I consistently asked questions during the 10 years he lived with CHF. Like, what if you’re not on a ventilator or a heart pump, but you’re brain dead? What if you’re not brain dead, but you can’t move at all? What if you’re on a heart pump, but not a ventilator and you’re comatose for more than two weeks? Would you want us to wait to see if you get better? How long?

“What the hell, Erin. Where’s the grave and how do I get my foot out?”

We laughed off some of the discomfort, but it’s a crappy conversation you have to have repeatedly. Ask again and with other questions after time passes; ask when other loved ones are around, if you can; ask them if they would answer differently with other people around, and why? Your loved one might not want everyone to know that they don’t want ongoing life sustaining treatment. If that’s the case it’s even more important to have ongoing conversations to avoid any misunderstanding, and to designate one person with power of attorney and to complete a healthcare directive. (These can be template forms or more detailed documents you can complete using services like LegalZoom if you can’t afford an attorney but be sure to get them notarized.)

Attack ambiguity like it’s a monster under the bed, because it is. While my Dad’s partner and I were with Dad waiting for rounds to get to us, I pestered his nurse with questions about the doctors and this huge contradiction between what the ICU doctor was recommending versus the cardiologist. I had no issue with airing every single conspiratorial thought.

“Is the cardiologist using Dad’s case for research on A-Fib or something? Does it look bad if he performs a surgery on someone who dies?? Is this because he had to be readmitted within a week of his last heart procedure and he’s afraid Medicare won’t pay?”

The nurse was patient, generously patient while she was overseeing patients during rounds. She explained to us, simply, that the cardiologist focuses only on the heart, not any other part of the body, let alone the entire system that works together to keep us alive. That is the role of a specialist. A cardiologist is there to determine whether a heart can and will keep beating, even when the entire system may not be able to sustain a beating heart. Unfortunately, Dr. A**hole doesn’t mention that to the worried human beings who are his patient’s loved ones.

If you are going to be responsible for a person’s end-of-life wishes, you also need to have every conversation possible with their healthcare workers. Not any healthcare worker, but the healthcare workers who are working with them directly. In the cacophony of bullsh*t advice you’ll get from family, friends, and everyone else who has ever used WebMD, the voices you need to hear are those of your loved one and the professional healthcare workers who understand their condition in all of its uniqueness. For the sake of keeping this “list-icle” to a “list-icle” length, I’ll leave it at that and rely on your ability to keep that conversation going yourselves.

After the conversation with his nurse, I felt really grateful for a chance to hear the generalist ICU doctor and cardiologist discuss my Dad in front of me. I wanted to see these two doctors debate with empirical data, like medical gladiators fighting to my Dad’s death.

A group of white coats eventually arrived at the room and quickly reformed their circle in the hallway. Dr. Big Eyes caught mine and motioned for us to join the circle. Dr. A**hole didn’t seem to notice I was there. There were two medical doctors, three or four pharmacists, two nurses, a respiratory therapist, and a palliative care social worker.

I was ready to be in the medical boxing ring and follow the lead of the person who won. It would have been easier if it had been like that. But it wasn’t. It wasn’t a debate. It wasn’t even a conversation. It was a series of statements of facts about Dad’s physiological system, with his worst case scenario happening in the room next to me.

Need-to-know #4: Remember that you are an advocate for your someone else’s decisions. Your priority is to protect and carry out their final wishes, not yours or anyone else’s.

Medical institutions tend to not prioritize palliative care, but that is changing. One way that’s changing is the growing presence of palliative care social workers in hospitals. Their role is to connect patients and their families with information and resources related to ensuring the comfort of patients who will never be “healthy” again and/or are in the end-of-life process. (I’m not practicing toxic positivity, I swear. I’m using “end-of-life” instead of “death” to reinforce the processual nature of dying.)

I thought professionals in hospice were the same as professionals in palliative care, but the roles are very different in one way. Palliative care professionals, especially social workers, are responsible for providing the emotional fortitude to protect and advocate for your own and your loved one’s final wishes. At that time, I was an independent and competent woman. I dare say it’s not just me, but it is all of us who become children when given the sole responsibility of “deciding” when someone will die. That’s what I told the palliative social worker when I met with her later that day, because rounds provided no new information, except that this episode would drastically alter his life and leave him dependent on others, if he survived at all.

“He doesn’t want this. He might not even wake up and he’s got this thing down his throat. I don’t know how to decide. How do people decide this? What the f&$k does that pro/con list even look like?” I looked to see if she thought that was as funny as I did. She offered a sympathetic smile.

“This is not your decision. You are NOT making a decision. You are carrying out what your father already decided he wants for himself.” Her voice was warm but steadied… confident but receptive. This stranger had no doubt that I knew my Dad well enough to understand what he wanted, even when he couldn’t tell me. I needed to hear that. I still wonder if all palliative social workers would be able to so skillfully balance compassion and strength to calm the chaos that was preventing me from protecting my dad’s final wishes.

Need-to-know #5: Don’t be afraid to say “shut up.”

Don’t tell any healthcare workers to “shut up,” that’s not what I mean. I mean don’t be afraid to tell your family and friends to “shut up” if they say anything except supportive words to you and each other during and after this entire process.

Maybe it’s better to choose softer language, maybe, when you’re actually in the moment when someone says, “Are you sure this is what he wants?” Go ahead and use the soft words, but I want you to hear “SSSHHHut up” in the back of your mind while you’re using those softer words. Unabashedly. Maybe “shut the f* up” would feel even better? Go for it.

As long as that voice is unquestionably clear that your loved one put you in this position because they trust you, literally, with their life. Don’t let anyone question that.

Erin M. Evans, Ph.D. is a candidate for the San Diego County Board of Education in District 4, a sociologist at San Diego Mesa College, faculty vice president for AFT 1931, and a volunteer Court Appointed Special Advocate for teenagers in foster care (CASA).