Victoria Woodhull Uncensored: The Life of the First Woman to Run for President

Book Report: Americana

By Mel Freilicher

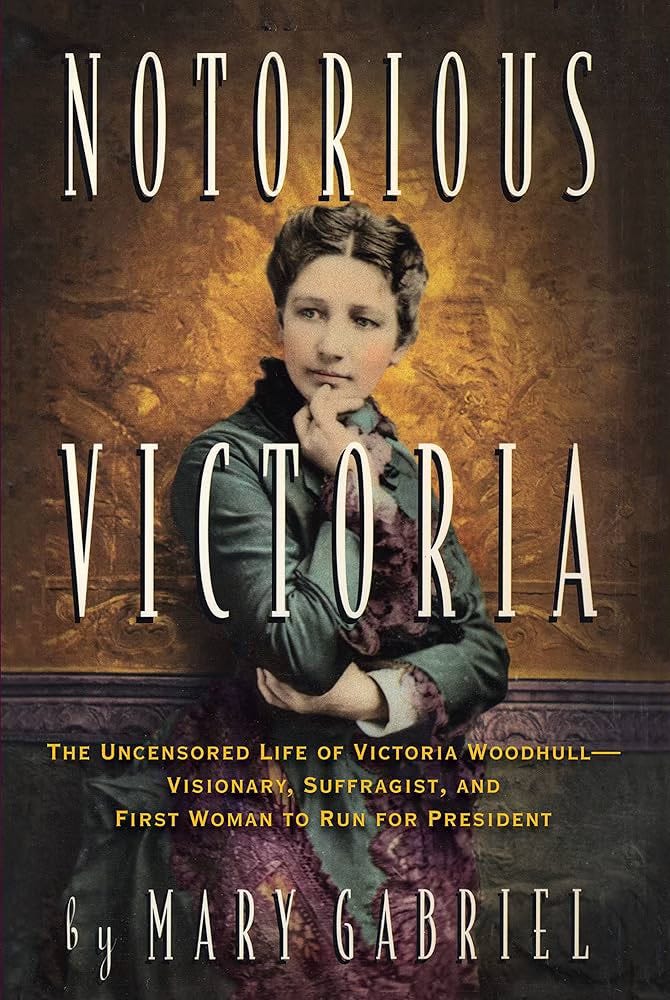

NOTORIOUS VICTORIA: The Uncensored Life of Victoria Woodhull—Visionary, Suffragist, and First Woman to Run for President by Mary Gabriel on Algonquin Books of Chapel Hill, 1998

1.

The banner on top of the back cover reads:

Victoria Claflin Woodhull (1838-1927) was the first woman to run for president, the first woman to address the U.S. Congress, and the first woman to operate a brokerage firm on Wall Street

So why was she written out of history?

In his eulogy, the Revered W.H.B. Yarborough, Rector of Brendon, declared, “She was in advance of her time, and accordingly suffered persecution.” The simple answer.

But her biography outlines a complex character, and fascinating life in which Victoria, a successful stockbroker (it would be another century before a woman would hold a seat in her own name on the New York Stock Exchange), was sometimes seen as head of the spiritualists, the suffragists, the labor movement, and other times more or less disavowed by them all.

A dedicated advocate of free love, she tried to bring these groups, and their ideals, closer together through lecture tours and the newspaper she published, and was too often viewed as betraying any one-cause movement.

Victoria Claflin was the sixth of ten children born in a “twenty-five foot long, one-story unpainted frame hovel” in Homer, a small town in the middle of Ohio, into “an indolent family that was considered the town trash.” Her father, Buck, “was a one-eyed one-man crime spree”: allegedly theft, counterfeiting, and arson.

He was known to beat his children with a willow or walnut tree switch that had been soaking in water “in anticipation of the character-building exercise.” After Buck burned down his gristmill for the insurance, the local Presbyterian Church held a fundraiser to buy a horse-drawn wagon and enough supplies to remove the family to Mount Gilead, another Ohio town where Victoria’s sister lived.

From Buck, Victoria “learned to bend, if not, break the law, and from her mother she learned to communicate with spirits.” A religious zealot, Anna was an abrasive personality and “as homely as her daughter was beautiful.” “Given to ecstasies whose nightly constitution most often included a trip to the local orchard” where Anna would pray loudly for the sins of the townspeople while cursing “till her lips were white with foam.” She could recite the Bible backwards!

Also “given to ecstasies” early in life, each experience offered Victoria “a visit to the netherworld through the intercession of a spirit guide”—convincing her she was destined for great things. Her “earthly education” consisted of a total of three years of elementary school, on and off between the ages of 8 and ll.

In 1848, a pair of young sisters in upstate New York, Kate and Margaret Fox, began to hear strange noises, “rappings,” and appeared to be able to communicate with the spirit,” Mr. Splitfoot.” Within a year, they had a paying audience, and in 1850 they were set up by P.T. Barnum in his hotel in New York City, holding demonstrations three times a day at a dollar per person. The Fox sisters “sparked an epidemic of spiritual encounters and by 1851 there were said to be thousands of mediums in every state.”

Even before this, Buck’s two daughters were exhibiting strange powers. Victoria believed she could communicate with her dead infant sister,” and through “spirit intervention,” she could heal the sick. And when Tennessee was just five, she predicted a fire so precisely, briefly she was suspected of starting it. Buck charged one dollar per visit to see his daughters, who from then on became the family’s primary breadwinners.

Arriving in Mount Gilead ostensibly to open a medical practice, within five months, Canning Woodhull married his young patient (who suffered from fevers and rheumatism) just two months into her 15th year. Soon discovering he was profligate—spending the third night of their marriage in a brothel—and probably not even a licensed doctor, within a year, Victoria gave birth to a son, Byron. She believed his mental retardation was due to her husband’s excessive drinking.

Although wives were basically chattel at this time, the 16-year-old wife and mother took charge of the penniless family and set off for San Francisco. The cry of “Gold” had reached the east in late 1848 when San Francisco listed 459 residents. By the time Victoria arrived, in the mid 1850’s, it boasted 40,000. Jobs were scarce for “respectable women” during the depression which hit the city after the Gold Rush rally.

It’s unclear how Victoria made a living: some say she “worked as a cigar girl in the morally fetid port section of the city known as the Barbary Coast, where, among other things, the topless waitress was born.” Gabriel suggests, “San Francisco was an exotic universe of depravity,” far different from anything Victoria had known in the Midwest, and she soon returned home. Her fortunes changed.

Buck had set up her younger sister, Tennessee, as a medium, billed in Columbus Ohio, as a “wonderful child…endowed with her birth from a supernatural gift”—supporting more than a dozen shiftless relatives. Victoria joined the family business as a spiritual healer in Indianapolis and Terre Haute, taking Tennie under her wing (they remained close companions for a large part of their lives).

Later, her sympathetic biographer, and lover, Theodore Tilton, wrote: “She straightened the feet of the lame; opened the ears of the deaf; she detected the robbers of a bank…she solved psychological problems…she prophesied future events.” She earned nearly $100,000 in one year!

Famously, the Civil War and its aftermath was the heyday of spiritualism. Three million men had served, and 690,000 had died. “What was left in its wake was widespread, misery, disease and decay.” Typhoid, malaria, dysentery, and pneumonia killed many who the guns missed. People were desperate to communicate with their departed loved ones. Lincoln himself said the terrible war “carried mourning to almost every home.”

Throughout the early years of the war, the Claflin family moved around in Ohio, Indiana, Pennsylvania, and Illinois, not necessarily together. Partly because they had to flee cities like Ottawa, Illinois where Buck claimed Tennie could cure cancer: she was charged with manslaughter when one of her patients died. Society in the 1860s often considered spiritualists and prostitutes to be one and the same. In 1865, the sisters were asked to leave Chicago and Cincinnati, where they’d set themselves up as clairvoyants--neighbors claimed they were operating a brothel.

Joining a medical road show touring Tennessee, Arkansas and Missouri, in St. Louis, Victoria met the man who changed her life: Colonel James H. Blood, Commander of the Sixth Missouri Regiment. At war’s end, he was elected City Auditor, and later became President of its Society of Spiritualists.

Consulting Mrs. Woodhull as a spiritualistic physician, he was startled to see her pass into a trance, during which she announced, unconsciously to herself, that his future destiny was to be married to her. This was the first time they’d met! “Thus to their mutual amazement, but to their subsequent happiness, they were betrothed on the spot by ‘the powers of the air.’”

Blood was unhappily married, too—and had children--which apparently mattered little to either lover. (Both eventually got divorced.) “Midcentury spiritualists believed in a spiritual affinity stronger than civil bonds” which would be evident through individual revelation. Everyone had a “natural mate with whom they would have a ‘love union of equals’ and a ‘true marriage.’”

Blood was described by one contemporary as an extreme radical of the most uncompromising type. Supporting women’s rights and social freedom for all, he introduced Victoria to many of the reform movements in which she would become prominent. “The lessons would have been easily learned,” Gabriel comments, since “Victoria had grown up outside the law…and had never been asked to conform to either a rigid family structure or a place in society.”

2.

Victoria’s spirit told her to move to 12 Great Jones Street in New York which also became the home of three sisters and their large families. The street was bounded by extremes—on one side, Broadway’s dance halls, brothels and saloons, “where upper-class clients could pay for liaisons. The other side by the Bowery was crowded with pimps, prostitutes, street gamblers, and “black-eyefixers.”

This city of churches had 621 houses of prostitution, 96 “houses of assignation,” and 75 “concert saloons” of ill repute that were as well attended as places of worship—and often by the same clientele. Home to the country’s most advanced thinkers, New York had also been the scene of the nation’s worst mob violence—the 1863 draft riot left l05 people dead. Neighborhoods were owned by gangs of marauders who exacted protection money, and “the bribe and blackmail were as much a part of finance as banking.”

On arrival, Victoria planned to take up the fight for women’s rights, quickly enlisting her first recruit, her younger sister. The more beautiful of the two sisters, Tennessee was “positively bewitching.” Having experienced neither a bad marriage nor a damaged child, her “look translated into a sexual rascality.”

Slightly plump, dimpled, and delightful, Tennessee was “possessed of a boyish carnality in an altogether feminine body.” Victoria was more aptly described as stormy. “Anger, passion, excitement” could transform the once full-bodied girl, grown into a “slim and elegant woman whose manner was surprisingly refined and reserved considering her family history.” She prided herself on not applying makeup or showing cleavage.

Again seeking out customers for his talented daughters, Buck found the golden goose—in the person of Cornelius Vanderbilt, Wall Street royalty who’d made millions in the shipping wars of the 1830s and ‘40s. Lacking the social airs that usually accompanied great wealth, Vanderbilt was a no-nonsense, unsentimental man’s man, described by one writer as “rugged, profane, barely literate, and extremely arrogant.”

The arrogance, “like everything else about Vanderbilt, was earned,” Gabriel comments. But the Commodore was on a losing streak. His wife, Sophia had recently died, and he’d lost seven million dollars to fellow Wall Street speculators, Jay Gould and Jim Fisk, “in a test of wills and fortunes over control of the Erie Railroad.” It was well-known Vanderbilt consulted spiritualists to communicate with his dead parents. He also entrusted the treatment of his heart and kidney problems to “magnetic healers” rather than medical doctors.

Tennessee was 22 when she met the Commodore, and quite experienced at the laying on of hands: supposedly magnetizing the patient, acting as a kind of electric prod to jolt his system back into shape. At his office, the Commodore bounced “the little sparrow,” as he called her, on his knee while talking railroad business. She told him jokes, read the newspaper to him, and pulling on his whiskers, called him “old boy.”

Victoria was helpful to Vanderbilt in a different way: using her powers as a seer to predict stock market trends. Like Victoria, Vanderbilt had a damaged child. His son was epileptic, and the Commodore blamed himself for having married his first cousin. Paying the two sisters generously, he opened the tap on stock tips. Financially armed, Victoria was ready to start her fight for women’s rights.

In January 1869, she traveled to Washington, D.C. to attend the First National Woman Suffrage Convention to be held there. By 1869, the movement was on the verge of a split, divided between the radicals, led by Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton, and the moderate New England women’s rights advocates, led particularly by the powerful Beecher family, who thought the vote should be won gradually state by state. Against their wishes, Stanton and Anthony had already proposed a sixteenth amendment to the Constitution securing women’s vote.

With the suffrage movement in a stalemate, Victoria came up with a new approach. Guided by Benjamin Butler, a Civil War general, shrewd congressman from Massachusetts and powerful orator: outspoken in his support for an eight-hour workday, women’s suffrage, and Irish nationalism. No new constitutional amendment was required to give women the vote, announced Victoria, because such protection already existed.

She wrote, “The question is forever settled by Article 1V of the Federal Constitution, Sec. 2, first clause, which says: ‘The citizens of each state shall be entitled to all the privileges and immunities of citizens in the United States.’” Women in Wyoming had already been allowed to vote in the election that November, thus all women had the right, the article reasoned, unless a convention was held to amend the Constitution.

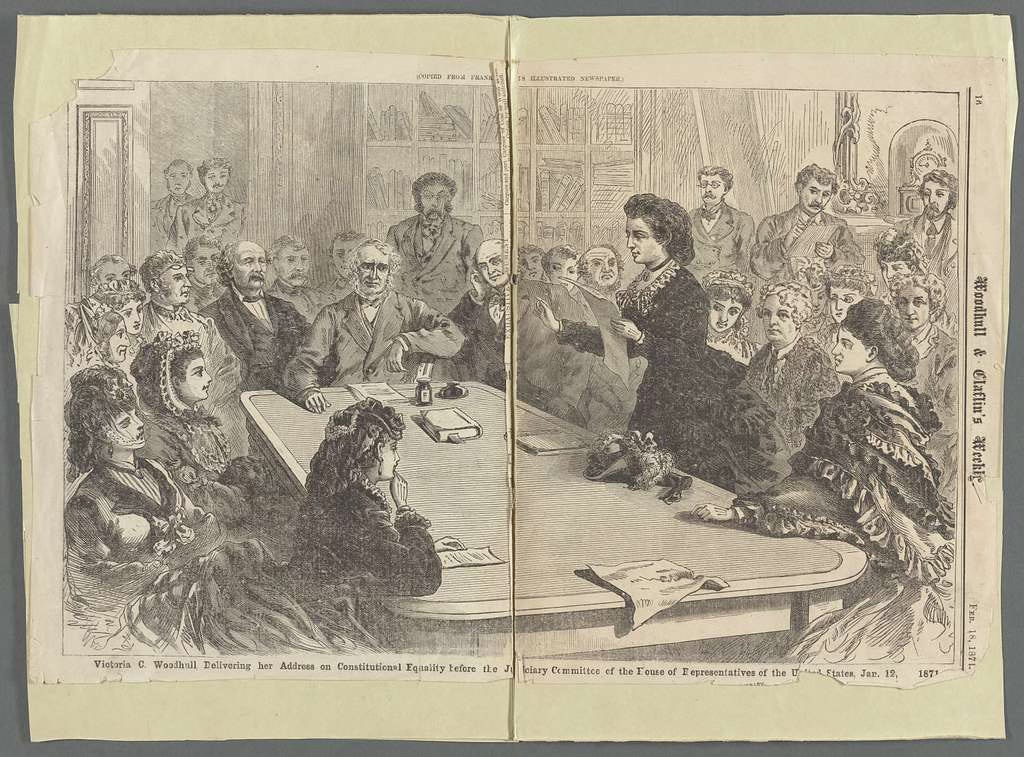

Butler said he would read the petition to Congress. But Victoria finally persuaded him to win her an invitation to address the committee herself. Despite annual requests from women reformers, no woman had ever before been allowed to address a congressional committee.

As she spoke, Aunt Susan, as Susan B. Anthony was known by the younger women in the movement, sat behind her--a public benediction from one of the pillars of the movement, signaling Victoria was welcome to join the cause. When the women’s rights convention got underway that afternoon, Victoria was named to the group’s National Committee of Women.

Only Butler and one other member of the congressional committee responded in support of granting women the vote. The majority opinion stated this was up to the courts and the state, not an issue for Congress to decide. Meanwhile, a group of 1000 women, including Catherine Beecher, General William Sherman’s wife, and the wives of prominent senators, congressmen and businessmen signed a petition against female suffrage.

They claimed to represent the majority of women in the country in the belief that the “Holy Scripture inculcates for women a sphere higher than and apart from that of public life…” In return, if the government wouldn’t help them, Victoria announced, they’d “proceed to call another convention, expressly to form a new constitution and to erect a new government.”

“We mean treason; we mean secession; and on a thousand times grander scale than that of the south. We are plotting revolution, we will overslough the bogus republic, and plant a government of righteousness in its stead.” Anthony wrote Victoria: “I have just read your speech. It is ahead of anything, said or written—bless you dear soul for all you’re doing to help strike the chains from women’s spirit.”

3.

The sisters were afraid they’d lost some access to Vanderbilt. His children had been “in the habit of procuring young women for their father, to feed his appetite and at the same time, control his associations.” They convinced him to marry one of them; at the same time, the Commodore planned to keep Tennessee as his “little sparrow.”

On September 24, 1869, “Wall Street crashed with a mighty thud after the investment banker Jay Gould tried to conquer the gold market.” With advice from Vanderbilt, Victoria sat in a carriage outside the gold exchange “gambling from morning to night.” Through the month after Black Friday, she continued to buy up bargains in a deflated market. By the end of the year, having netted a profit of more than $700,000, Victoria was wealthy beyond her dreams.

She’d lost money too. As a woman, Tennessee was not permitted on the trading floor when she was dispatched to sell failing gold. In 1868, Elizabeth Cady Stanton had issued a call in her newspaper: “Let women of wealth and brains step out of the circles of fashion and folly, and fit themselves for the trades, arts and professions and become employers instead of subordinates.” Heeding that call, Victoria “officially and very publicly crossed the threshold into the man’s world of Wall Street.”

With the assistance of James Blood (always an effective strategist and propagandist for his wife), and Vanderbilt, the sisters opened an office on the stock exchange, gaining a great deal of publicity. Headlined as “Queens of Finance,” Future Princesses of Erie,” and “Vanderbilt’s Protégés,” they were front page news in the New York Herald; the media continued favorably reporting on them.

At this time, 5 of the 40,736 lawyers in the United States were women, 67 women were among the 43,874 clergymen, and 525 women had penetrated the medical profession which numbered 62,383 male members. No women were on Wall Street.

Although she’d been visited twice by Susan B. Anthony who’d written two flattering articles about her, this “still did not elevate Victoria In the ranks of the women’s right activists.” Deciding her place among women reformers was not in the ranks but at the top, at thirty-two, Victoria declared herself a candidate for President of the United States. “It was, at the very least, a precipitous step,” Gabriel remarks. No woman had ever been elected to Congress, let alone the White House, and Victoria had no political party behind her and no political experience.

“But Victoria’s style had never been measured or deliberate.” The Herald had given her a weekly column and she used her first entry, on April 2, 1870, to announce her candidacy. Three days after the announcement, Victoria leased a mansion in New York’s Murray Hills section, creating “a sumptuous palace inside, more befitting for a leader of her people” than her current brownstone.

Her candidacy was viewed as a novelty by the press. “The men who pulled the city’s financial and political strings…felt no threat from this charming renegade in petticoats,” visiting Victoria at her home and office. “She was allowed to roam Wall Street and dabble in politics in much the way a benevolent husband allowed his wife to exceed her household budget or join the temperance movement. Victoria was treated as a pet.”

Not always being able to count on favorable press coverage, and needing a vehicle to broadcast the seriousness of her candidacy, “and that she was a force to be reckoned with, not merely tolerated,” Victoria bought herself a voice. “Victoria Woodhull, the stockbroker and presidential candidate, would become a publisher.”

4.

Americans had become addicted to newspapers during the Civil War, and by the 1870s the press was a dominant force in the national dialog. One contemporary social historian wrote: “The newspaper is half the life of an American. Even in some prisons they supply each criminal with the morning prints…to deprive him…is too shocking a cruelty for Americans to think of inflicting.”

Each political party had its own paper; criminal syndicates controlled others. “The news could be bent, bought, or sold to promote a position or person. It could be more editorial than fact and embellished to the point of fiction.” Two major newspapers on the east coast advocated women’s rights: The Woman’s Journal started in Boston in 1870 and Anthony’s and Stanton’s more radical, Revolution. Neither had a wide circulation; “like the women’s conventions, they primarily preached to the converted.”

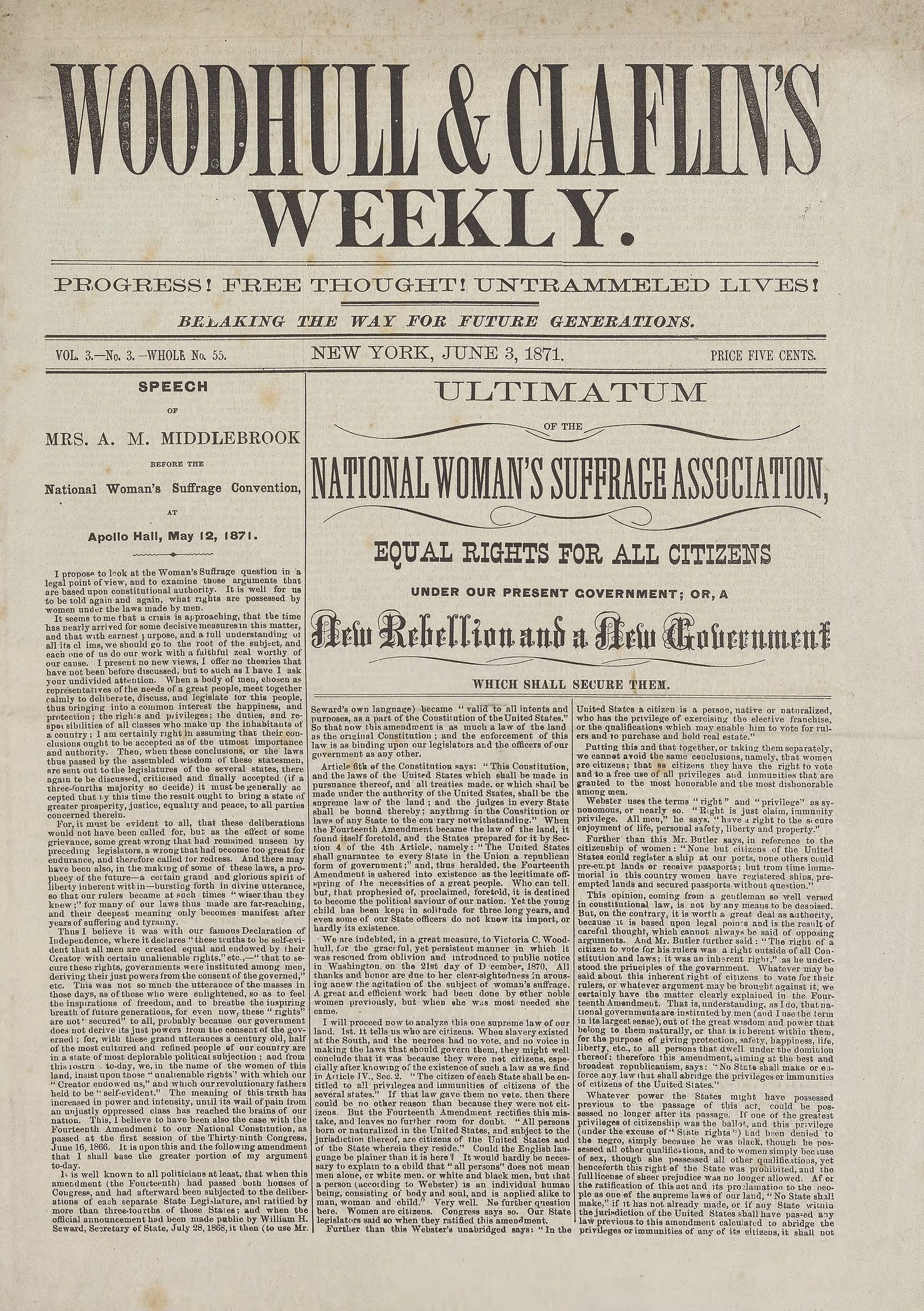

On May 14, 1870, the first issue of Woodhull & Claflin’s Weekly was published out of an office on Park Row, the center of newspaper activity in the city, under the banner “Upward & Onward.” Featuring a front page story by George Sand, on page 8 of 16, a statement of purpose, most likely written by Blood, read in part:

]“This journal will be primarily devoted to the vital interests of the people and will treat all matters freely and without reservation. It will support Victoria C. Woodhull for President with its whole strength, otherwise it will be untrammeled by party or personal considerations…and will advocate Suffrage without the distinction of sex!”

Interspersed among bylined articles by contributing writers were unsigned ones, presumably by Blood, on topics ranging from “Women as a Political Element,” “Women and Prisons, “Education and Street Cleaning,” and “Capital Punishment.” The paper attracted some serious, well-known male writers who, in turn, brought in others. The Weekly made the splash Victoria was looking for—suddenly she was being recognized as the new woman.

This muckraking paper exposed police involvement in prostitution, insurance scams and railroad bond schemes. Coming under attack, they doubled down with such bold titles as “The Stupendous Intended Frauds, Spurious (Counterfeit) Mexican Bonds,” and “The Outrages of Corporations.” Vastly increasing its numbers of enemies, but also attracting a new audience of admirers, the Weekly became a player in the country’s burgeoning labor movement.

Largely as a result of widespread corruption in the administration of President Ulysses S. Grant, by 1870 industrialists, corporations, utilities, bankers and brokers were viewed as an enemy of the working class whose wages had stagnated while millionaires added to their coffers. Of course, the l9th century saw a huge shift in the labor force—workers went from being independent tradesmen to wage earners, particularly in large factories. Millions of immigrants swelled the population of U.S. cities, and women were joining the labor force.

Labor unions also relied on newspapers to get their message out. The Weekly was able to step into the void created by the closing of one of the strongest voices for the mass of German-born workers, the Arbeiter-Union, which left only French language publications to spread the labor message in New York City.

In the fall of 1870, the Weekly had a very respectable circulation of 20,000, and, except for Blood who continued to shun the limelight, the paper’s staff received even more press coverage. Victoria’s home had become a salon where bankers mingled with labor leaders “in front of countless floor-to-ceiling mirrors, judges rubbed shoulders with thieves under glistening chandeliers, and women’s rights advocates could press their cause with newspaper editors next to bronze statuary of coupling gods and goddesses. It was a sanctuary of free speech and free thinking.”

5.

“Newspapers began taking a second look at this woman they had eagerly embraced as a broker and publisher and found they were less enamored of her as reformer and a politician.” In the drawing rooms, for women “who wanted to influence society but had no political voice…gossip was their only tool.” They excoriated Tennie for her excesses: in the public’s eye, the sisters “were largely the same person.” Attacking Victoria for the sin of being “ambitious,” they called her a Jezebel for her weakness for men with ideas.

Envoys representing businesses which had been unmasked as corrupt were visiting the Weekly’s offices trying to shut it down. Other papers were trying to cut the paper’s circulation by petitioning newsstands to stop carrying it. The Herald, where Victoria had been a columnist, was particularly vicious.

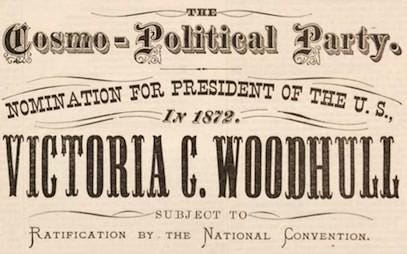

Still with supporters, in 1871, Victoria was keynote speaker at the National Woman’s Suffrage Association which met to rally around her pronouncement: women were already guaranteed the right to vote under the 14th and 15th amendments. She went on to read the platform of her new Cosmopolitical Party which called for a complete overhaul of the U.S. government, including:

“A one term presidency with a lifelong seat in the Senate, afterwards; reform of the civil service; an eight-hour workday; reform of the monetary system, interstate commerce; tax reform; abolition of the death penalty; instituting a form of welfare for the poor; national public education, and the establishment of an international tribunal to settle international disputes, and maintain an international army and navy.”

Victoria’s bold positions “electrified” the audience, and the platform was adopted.

Soon afterwards, the gossips had a field day when Victoria’s “eccentric (if not insane) mother dragged Col. Blood into court on charges that he’d threatened to kill her.” Denying the charges, naturally, Blood did testify he and Victoria lived in the same house as Dr. Woodhull, so the Doctor could take care of his “idiotic” son. The next day, Victoria testified to their cohabitation, with no explanation.

Later, in a letter to the New York Times, she wrote: “Dr. Woodhull being sick, ailing and incapable of self-support, I felt it my duty to myself and to human nature that he should be cared for, although his incapacity was in no wise attributable to me. My present husband, Col. Blood, not only approves of the charity, but co-operates in it. I esteem it one of the most virtuous acts of my life…”

The next day’s headlines cried “Free Love!”

Free love, according to one social historian, “perhaps the single most odious epithet one could attach to a respectable citizen of the post-Civil War era,” was used to sink more than one reformer. Of course, it was accepted men would have liaisons outside of marriage with “fallen women” and bachelors would have mistresses. During the 1870s, 80% of men seeking a divorce stated as their reason, “the failure of their wife to be a submissive helpmate.” Free lovers, of course, did not believe women were obliged to be submissive.

6.

There was a saying in Boston in 1871, “mankind was divided into three classes—the good, the bad, and the Beechers!” The Rev. Lyman Becher and his three wives (none acquired through divorce) bred a “noble stock of writers, reformers and clergymen” who set the standard for middle-class Americans. “Three of the Beecher children would conspire to ruin Victoria Woodhull.”

It was disheartening for me to discover Harriet Beecher Stowe was among the most vitriolic and cunning. Opening shots came in “My Wife and I,” a serial she began writing for the Christian Union. Introducing a character named Audacia Dangyereyes, depicted as a “lusty, badly spoken political candidate and editoress of a newspaper… who hoodwinked innocent men into subscribing by refusing to leave their offices till they did.”

The battles got much worse, as Victoria doubled down on free love—for her, usually meaning monogamy, without the burden of divorce which forced women to lose their children and often their property. But the real problem lay much deeper. Harriet’s older brother, Henry Ward Beecher, powerful head pastor of Brooklyn’s well-established Plymouth Church, was, in fact, a “free lover,” but too cowardly to admit it. Henry conspired mightily with his two sisters to save his reputation.

Beecher’s affair with Elisabeth Tilton, the wife of his assistant, was a matter of gossip among the cognoscenti, when Victoria began her own infamous affair with Elisabeth’s husband. Thomas Tilton. poet and journalist, always sympathetic to Victoria’s causes, was described as “unquestionably the most popular young man in America.” Tall, handsome in a delicate way with thick wavy auburn hair, one contemporary called him a “perfect Adonis with whom any woman of sentiment and refinement would fall in love.”

In the Independent (the most profitable religious journal in the world; after Tilton took it over its readership swelled to 60,000) Tilton went so far as to declare “marriage without love is a sin against God.” Widely condemned, he ultimately lost his jobs, then wrote an admiring biography of Victoria.

But the downhill path was by no means straight. Reinvigorated, Victoria became emboldened in print. Likewise, her allies began risking reprisals, publicly defending her against powerful detractors. She was elected president of the American Association of Spiritualists. A mysterious group calling itself the Victoria League—rumored to have Vanderbilt’s backing—announced she was their candidate for the presidency under the Equal Rights Party. Unbeknownst to him, Frederick Douglass was nominated as Vice President.

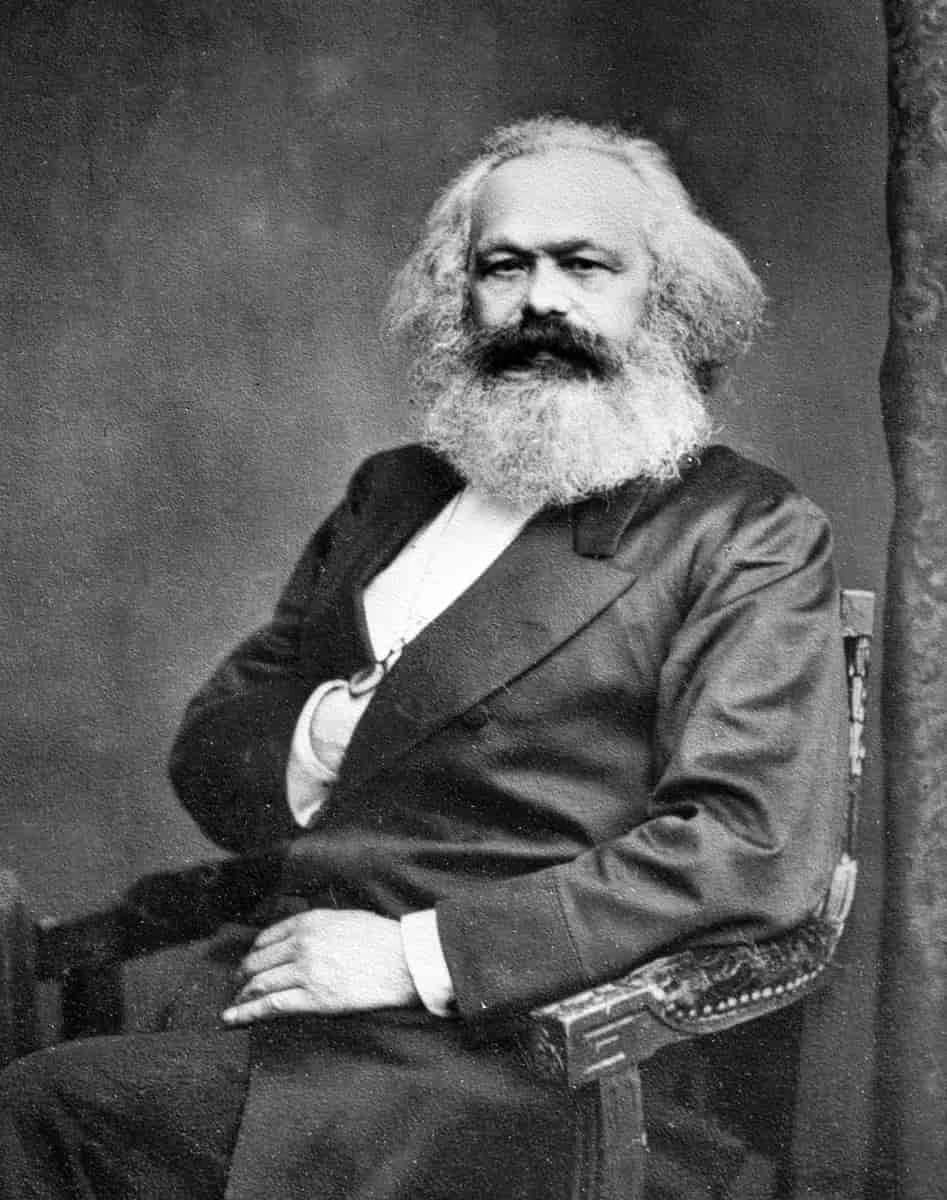

In March 1871, the Commune of Paris has been reestablished as an opposition government to the Third Republic in France. The revolutionaries were linked to Karl Marx’s IWA: founded in London in 1864, it sprouted branches in various European capitals and every large city in the United States. The IWA only had several thousand members in the U.S., but the press put the number at 300,000.

Joining the newly formed branch of the International Workingmen’s Association (IWA), Victoria took a front seat among American communists: she and Tennie were named heads of the IWA’s Section 12 in New York City, which, having a personality at its head and instant publicity at its disposal, soon became the leading American section. Her Weekly featured news on the Internationals and reprinted an interview with Karl Marx.

Late in 1871, the Weekly published the first American edition of Karl Marx’s Communist Manifesto. At the Academy of Music, “the heart of bourgeois New York,” Victoria gave a speech entitled “The Impending Revolution.” The turnout was enormous and chaotic. At its conclusion, “the applause was deafening,” continuing for ten minutes after she left the stage.

But this was a movement in which she no longer held an official position. Section 12 had been ousted from the American council of the IWA for alienating workers with its radical positions on social issues. How could Irish Catholic workers possibly be expected to support the notion of free love? Karl Marx himself said it was inevitable, because the group was spreading discord among the IWA ranks.

Victoria’s base was falling apart, primarily because she was aligning too many of her causes together. Endorsing the IWA platform on working conditions, Victoria added to that the support of women’s suffrage, and free love.

Then, calling for a People’s Party convention, Victoria signed the names of other suffragist leaders. But many, especially Susan B. Anthony, were loyal to the one issue of securing women’s right to vote. At the platform, Victoria announced a meeting the following day to discuss the rights of all humankind. Her connections with Anthony were completely severed.

Victoria was expunged from the record of the women’s movement, in the six-volume account of the early movement, considered definitive, compiled by Anthony and Stanton. Even more so, in Anthony’s personally sanctioned and supervised biography, written by Ida Harper.

7.

Victoria was broke. Rapidly evicted from several homes, as “the presidential candidate of the head of a ‘red party’ of ‘free lovers,’” she was unable to keep her 11-year-old daughter, Zulu, in private school-- other parents objected to a possible Woodhull taint. In June, 1872, Victoria, her two children, Blood, and Tennie were forced to sleep at the brokerage office one night.

But that landlord had also tired of his tenants and raised their rent prohibitively; they moved to a cheaper office. Soon, “Victoria’s pet, The Weekly, suspended publication.” Sued for her debts, she claimed she didn’t even own the clothes on her back.

Several months later, Woodhull & Claflin’s Weekly was revived, in order to publish in excruciating detail, what, and how, Victoria came to know about Henry Ward Beecher’s extramarital affairs (which, by then, Elizabeth Tilton had openly attested to). All hell broke loose. Although the scandal was national, none of the debris seemed to land on the upright preacher. Victoria was briefly jailed on obscenity charges. And Tilton’s career was more or less ruined.

Also in the scandal issue was a piece by Tennie detailing the seduction of two young girls by a Wall Street trader named Louis Chaillis. After having sex with them,” he boasted the bloody proof of the loss of the girls’ virginity on his finger.” Like the obscenity trial, the verdict in this criminal libel case, which put the sisters in the Tombs for a few months, was Not Guilty. “Upon which the judge told the jurors their decision was ‘the most outrageous verdict ever recorded, it is shameful…’”

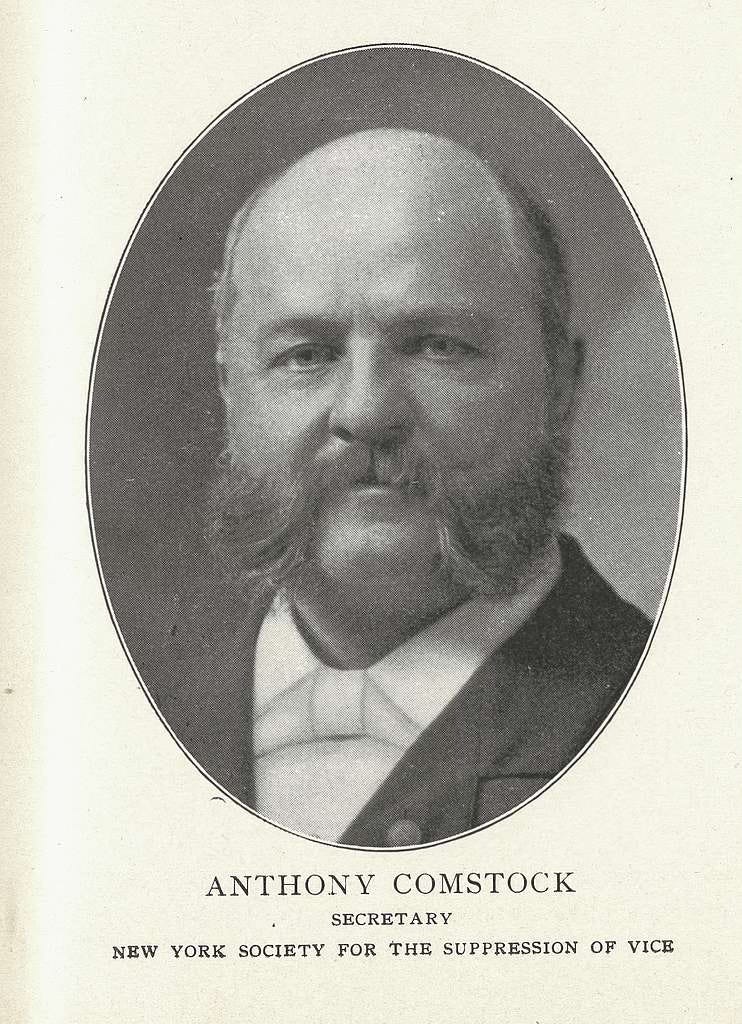

The infamous Anthony Comstock had brought the charges to federal court, claiming obscene material was sent through the mails, as pornography often was. The paper contained two words which he defined as obscene: token and virginity. A former dry goods salesman turned moral crusader, armed with a shotgun, Comstock single-handedly tried to rid his Connecticut hometown of rabid dogs. Next came liquor, then pornography.

“A large man with thick whiskers, a tight mouth, a bull-like neck and short tree-trunk legs,” he bought his shoes at the shop which supplied the police and fire departments. One writer said the nearest Comstock came to being festive was during the Christmas season, when he exchanged his black tie for a white one. He’d married a woman ten years his senior--described as “inveterate in her silence and always dressed in black.”

Captain Blood as well as several of the printers were also charged and spent some time in jail. The prosecutor in this case was a General, a member of Beecher’s Plymouth Church board. Victoria and Tennie’s lawyer, William F. Howe, was “without question the greatest criminal lawyer of the day.” With his partner, Abraham H. Hummel, they defended more than 650 persons indicted for murder or manslaughter. They also represented major brothel owners, a nationwide syndicate of pickpockets, one of the toughest of the 19th century gangs, the Whyos, the abortionist Madame Reztall, and significant celebrities such as John Barrymore, PT Barnum, Edwin Booth, Lillie Langtry.

In the middle of her ordeal, Victoria became severely ill, and almost died. (The Chicago Tribune reported this “as a dodge to create sympathy.”) At the end of the witch hunt, each sister owed about $60,000. Blood, Victoria, and Tennie all futilely petitioned Congress for the losses they had sustained as a result of the obscenity case.

During this time, a Woman’s Congress was held in New York. In a separate, standing room only crowd at the Cooper Institute, Victoria gave her last fiery speech, advocating for the rights of “the lower million” over the “upper ten.” The recent Wall Street crash, she warned, indicated the government, too, was about to fall. The four thousand people crammed into the hall were so eager to hear Victoria, they drove the preliminary speakers off the stage. Victoria predicted the “ignorant slaves” would be freed.

8.

“After being jailed, harassed, condemned, and impoverished,” Victoria’s Weekly changed, going over “wholly from politics to religion.” Arguing this was not a radical departure, Gabriel states, “Much of the theory of social freedom she had previously preached was founded in the Paulist socialism of the 1850s.” Her lectures were now geared toward purity of soul and body.

Six years later, due to Victoria’s continued physical illness, lack of money and the financial depression of 1876, the Weekly was forced to close permanently. She also filed for divorce from Blood, saying she’d found him with another woman. Gabriel comments, “No doubt the reasons for the split were many and complex, but adultery was most likely not among them.”

An unexpected windfall enabled the sisters to move to London. Cornelius Vanderbilt died with an estate worth $100 million (exactly what the U.S. Treasury had on hand at that moment). His son, William, anticipating many legal challenges to the will, reputedly gave the sisters more than $100,000 on condition they not be available to testify when the trials began.

By 1880, Victoria’s relations had crossed the ocean, too. “The raucous brood that had scandalized New York City was now on hand to wreak similar havoc in infinitely more staid London.” But the aristocrat, John Martin, who’d heard Victoria speak in London, began to court her, renting a place next to her family’s residence so he could spend time alone with her.

Victoria and John Martin were married at South Kensington Presbyterian Church in the presence of Buck Claflin and Tennessee. No one from Martin’s family attended. They moved into a home in Hyde Park Gate, an expensive block of urban mansions, with extensive gardens which “seemed enchanted and alive with greenery.”

At 54, Victoria had been solely a wife and mother for ten years, “in a period of prolonged convalescence.” With the help of her husband and daughter, she planned a new newspaper. The Humanitarian, like the Weekly, would mix politics, women’s rights, finance and fiction. Leaving aside religion, she now looked to social science as “her savior.”

Her fundamental tenet: in order to perfect society, breeding had to be controlled. For most of her career, Victoria had proposed women be given the right to determine by whom and when to have a child, but by the 1890s she seemed to have abandoned her hope of women asserting their rights in the bedroom. Theorizing, instead, society should intervene.

Among other things, she proposed better education for women to prepare for motherhood, also improved prenatal and postnatal care. “Her ideas raised eyebrows, not because of their eccentricity or their implications for social engineering, but out of fear that the poor would be made strong to the detriment of the wealthy.”

This concept of selective breeding, born in the American reform communities of the 1850s, in 1869 was given the name “stirpiculture” by John Humphrey Noyes, funder of the Oneida community. Victoria’s approach was a common one, viewing breeding within the animal world. Eugenics became immensely popular in the 1930s; even Margaret Sanger, major birth control advocate, briefly discussed breeding a race of “thoroughbreds.” Hitler, of course, derived many of his lethal ethnic cleansing ideas from the American eugenics movement.

Continuing to publish the cogent and critical Humanitarian, Victoria’s life further crumbled in 1895. She was sick, so was her husband with an undiagnosed ailment. After Martin’s death, Victoria’s publication addressed the possibility of an afterlife and dwelled on her growing horror of disease. Including a series of articles on the spread of infection, and the presence of germs on telephones, in rail carriages, and on circulating library books.

The war effort “and the Anglo-American alliance were Victoria’s final spurts of activity.” She and her daughter, Zula (she changed it from Zulu) developed a village Manor House into a residential college for women to learn the principles of agriculture--the tendency toward small-acreage farms had made this prospect more relevant. At its peak, the school had thirty students, “but it was neither successful nor long-lived.” Zula turned it into a club offering recreation to both men and women.

Victoria, and chiefly her daughter, also started an elementary school in a building they owned in a small village--appearing to be a model of education and attracting children from up to three miles away. Despite its popularity, it was closed after a few months. The school didn’t meet governmental standards, partly because its founders had failed to consult beforehand with the Worcestershire County Council or the local school board.

In subsequent years, Victoria became the village’s “fairy godmother,” earning her the title of “Lady Bountiful.” The unseen presence who gave the residents elaborate Christmas presents and gifts, she turned her barn into a theater for the village’s entertainment, supported youth movements, and allowed the Boy’s Brigade to hold its camp on the grounds of the estate. For the larger war effort, she worked for the Red Cross.

Victoria died in her sleep in 1927 at the age of eighty-eight. Only six mourners were present at the private service: her son and daughter not among them. Nor was Tennessee, who Victoria hadn’t seen for years: she’d remarried, moved back to New York, and continued to receive unfavorable publicity.

Victoria said she simply wanted to be remembered by a line from Kant: “You cannot understand a man’s work by what he has accomplished but by what he has overcome in accomplishing it.”

Mel Freilicher retired from some four decades of teaching in UCSD's Lit. Dept./ writing program. He was publisher and co-editor of Crawl Out Your Window magazine (1974-89), a journal of the experimental literature and visual arts of the San Diego/Tijuana region. He's been writing for quite some time. He is the author of The Unmaking of Americans: 7 Lives, Encyclopedia of Rebels, American Cream, and most recently, Privilege and Power: The Novel, all on San Diego City Works Press.